The Age of Infrastructure: the Triumph and Tragedy of the Progressive Civil Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Norris Dam State Park 125 Village Green Circle, Lake City, Tennessee 37769 / 800 543-9335

Birds of Norris Dam State Park 125 Village Green Circle, Lake City, Tennessee 37769 / 800 543-9335 Waterfowl, great blue and green herons, gulls, osprey and bald eagle frequent the lake, and the forests harbor great numbers of migratory birds in the spring and fall. Over 105 species of birds have been observed throughout the year. Below the dam look for orchard and northern orioles, eastern bluebirds, sparrows and tree swallows. Responsible Birding - Do not endanger the welfare of birds. - Tread lightly and respect bird habitat. - Silence is golden. - Do not use electronic sound devices to attract birds during nesting season, May-July. - Take extra care when in a nesting area. - Always respect the law and the rights of others, violators subject to prosecution. - Do not trespass on private property. - Avoid pointing your binoculars at other people or their homes. - Limit group sizes in areas that are not conducive to large crowds. Helpful Links Tennessee Birding Trails Photo by Scott Somershoe Scott by Photo www.tnbirdingtrail.org Field Checklist of Tennessee Birds www.tnwatchablewildlife.org eBird Hotspots and Sightings www.ebird.org Tennessee Ornithological Society www.tnstateparks.com www.tnbirds.org Tennessee Warbler Tennessee State Parks Birding www.tnstateparks.com/activities/birding Additional Nearby State Park Birding Opportunities Big Ridge – Cabins, Campground / Maynardville, TN 37807 / 865-471-5305 www.tnstateparks.com/parks/about/big-ridge Cove Lake – Campground, Restaurant / Caryville, TN 37714 / 423-566-9701 www.tnstateparks.com/parks/about/cove-lake Frozen Head – Campground / Wartburg, Tennessee 37887 / 423-346-3318 www.tnstateparks.com/parks/about/frozen-head Seven Islands – Boat Ramp / Kodak, Tennessee 37764 / 865-407-8335 www.tnstateparks.com/parks/about/seven-islands Birding Locations In and Around Norris Dam State Park A hiking trail map is available at the park. -

Ger.* One of the Common Beliefs of Lawyers, and Particularly of Aca- Demic Lawyers, Is That We Can Save the World Through the Processes of Law

THE POWER BROKER: ROBERT MOSES AND THE FALL OF NEW YORK. By Robert A. Caro. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974. Pp. 1246. Clothbound $17.95. Paperbound $7.95. Reviewed by Peter D. Jun- ger.* One of the common beliefs of lawyers, and particularly of aca- demic lawyers, is that we can save the world through the processes of law. This belief is a source of comfort, and perhaps of inspiration, to the profession, but there is some reason to wonder just how great an impact "law" does have in really shaping events when confronted by big questions-or big men. The story unfolded in Robert Caro's book, The Power Broker, Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, offers a case in point. Caro is not a lawyer, and therefore perhaps not a firm believer in the efficacy of law. He is a journalist, mesmerized by the rising and falling of New York and of that shadowy colossus, Robert Moses. As a result, he is able to expose, within his mosaic of a decaying city, not only the stork ornamenting the bathouse of Corona Pool "wearing an expression that made him look as if he were puz- zling over the physical differences in the creatures he had brought into the world,"' but also a paradigm of our most troubling problem, the irrational structure of our policy. Caro, the reporter, stands at the opposite pole from most legal writers and some of the political scien- tists. He supplies us, not with principles and definitions, but with a mass of facts of the sort that resist quantification. -

Finding Aid for the Post-Presidential Correspondence with Gerald R. Ford

Guide to the Post-Presidential Correspondence with Gerald R. Ford (1976-1993) Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum Contact Information Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum ATTN: Archives 18001 Yorba Linda Boulevard Yorba Linda, California 92886 Phone: (714) 983-9120 Fax: (714) 983-9111 E-mail: [email protected] Processed by: Susan Naulty and Richard Nixon Library and Birthplace archive staff Date Completed: December 2004 Table Of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Administrative Information 4 Biography 5 Scope and Content Summary 7 Related Collections 7 Container List 8 2 Descriptive Summary Title: Post-Presidential Correspondence with Gerald R. Ford (1976-1993) Creator: Susan Naulty Extent: .25 document box (.06 linear ft.) Repository: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum 18001 Yorba Linda Boulevard Yorba Linda, California 92886 Abstract: This collection contains correspondence relating to Gerald and Betty Ford and Richard Nixon from 1976 to 1993. Topics discussed include Presidential Museums and Libraries, a proposed Presidential pension increase, POW/MIA affairs, get well messages, and wedding announcements for the Ford children. 3 Administrative Information Access: Open Publication Rights: Copyright held by Richard Nixon Library and Birthplace Foundation. Preferred Citation: “Folder title”. Box #. Post-Presidential Correspondence with Gerald R. Ford (1976-1993). Richard Nixon Library & Birthplace Foundation, Yorba Linda, California. Acquisition Information: Gift of Richard Nixon Processing History: Originally processed and separated by Susan Naulty prior to September 2003, reviewed by Greg Cumming December 2004, preservation and finding aid by Kirstin Julian February 2005. 4 Biography Richard Nixon was born in Yorba Linda, California, on January 9, 1913. After graduating from Whittier College in 1934, he attended Duke University Law School. -

Elections Come and Go. Results Last a Lifetime. Market Declines and Recessions

A review of U.S. presidential elections Elections come and go. Results last a lifetime. Market declines and recessions Set your sights on the long term CLOSED CLOSED Investor doubts may seem especially prevalent during presidential election years when campaigns spotlight the country’s challenges. Yet even with election year rhetoric amplifying the negative, it’s Overseas conflict Businesses going important to focus on your vision for the future. and war There have always been bankrupt “ The only limit to tumultuous events. our realization of Keep in mind the following: The current economic and political challenges tomorrow will be our • Successful long-term investors stay the course and rely on time may seem unprecedented, but a look back doubts of today.” rather than timing. shows that controversy and uncertainty • Investment success has depended more on the strength and have surrounded every campaign. — Franklin D. Roosevelt resilience of the American economy than on which candidate CLOSED or party holds office. CLOSED • The experience and time-tested process of your investment manager can be an important contributor to your long-term Weather-related investment success. Civil unrest and calamities protest CLOSED Labor market struggles 1936 1940 1944 1948 1952 1956 1960 1964 1968 1972 1976 1980 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 2012 2016 Democrat Republican Franklin D. Franklin D. Franklin D. Harry Truman Dwight Dwight John F. Kennedy Lyndon Johnson Richard Nixon Richard Nixon Jimmy Carter Ronald Reagan Ronald Reagan George H.W. Bill Clinton Bill Clinton George W. Bush George W. Bush Barack Obama Barack Obama Donald Trump Roosevelt Roosevelt Roosevelt vs. -

The Prez Quiz Answers

PREZ TRIVIAL QUIZ AND ANSWERS Below is a Presidential Trivia Quiz and Answers. GRADING CRITERIA: 33 questions, 3 points each, and 1 free point. If the answer is a list which has L elements and you get x correct, you get x=L points. If any are wrong you get 0 points. You can take the quiz one of three ways. 1) Take it WITHOUT using the web and see how many you can get right. Take 3 hours. 2) Take it and use the web and try to do it fast. Stop when you want, but your score will be determined as follows: If R is the number of points and T 180R is the number of minutes then your score is T + 1: If you get all 33 right in 60 minutes then you get a 100. You could get more than 100 if you do it faster. 3) The answer key has more information and is interesting. Do not bother to take the quiz and just read the answer key when I post it. Much of this material is from the books Hail to the chiefs: Political mis- chief, Morals, and Malarky from George W to George W by Barbara Holland and Bland Ambition: From Adams to Quayle- the Cranks, Criminals, Tax Cheats, and Golfers who made it to Vice President by Steve Tally. I also use Wikipedia. There is a table at the end of this document that has lots of information about presidents. THE QUIZ BEGINS! 1. How many people have been president without having ever held prior elected office? Name each one and, if they had former experience in government, what it was. -

Returning Peer Review to the American Presidential Nomination Process

40675-nyu_93-4 Sheet No. 65 Side A 10/16/2018 09:18:32 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\93-4\NYU404.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-OCT-18 11:08 RETURNING PEER REVIEW TO THE AMERICAN PRESIDENTIAL NOMINATION PROCESS ELAINE C. KAMARCK* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 709 R I. THE OLD DAYS: WHEN POLITICIANS NOMINATED OUR LEADERS ................................................ 710 R II. FROM THE NEW PRESIDENTIAL ELITE TO SUPERDELEGATES ....................................... 713 R III. IS IT TIME TO BRING BACK PEER REVIEW? . 719 R IV. PEER REVIEW IN AN AGE OF PRIMARIES? . 722 R A. Option #1: Superdelegates . 724 R B. Option #2: A Pre-Primary Endorsement . 725 R C. Option #3: A Pre-Primary Vote of Confidence . 726 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 727 R INTRODUCTION As Americans, we take for granted that those we entrust with significant authority have been judged by their peers to be competent at the task. Peer review is a concept commonly accepted in most pro- fessions. For instance, in medicine “peer review is defined as ‘the objective evaluation of the quality of a physician’s or a scientist’s per- formance by colleagues.’”1 That is why we license plumbers, electri- cians, manicurists, doctors, nurses, and lawyers. We do this in most 40675-nyu_93-4 Sheet No. 65 Side A 10/16/2018 09:18:32 aspects of life—except politics. In 2016, Americans nominated and then elected Donald Trump, the most unqualified (by virtue of tradi- tional measures of experience and temperament) person ever elected to the Office of the President of the United States, in a system without * Copyright © 2018 by Elaine C. -

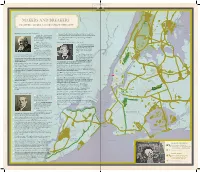

Makers and Breakers

Confidential property of University of California Press Uncorrected proofs Not for reproduction or distribution Van 12 Cortlandt Park 10 MAKERS AND BREAKERS Van Co-op Cortlandt City OLMSTED, MOSES, JACOBS SHAPE THE CITY Pelham Bay Village Park Long Island Sound frederick law olmsted (1822–1903) 14 1963–65: Presides over transformation of Flushing Meadows for BRONX o Cr ss Br onx 1 August 1840: Arrives in New its second world’s fair, which flounders in finances and attendance 11 Ex py York at 18, from Connecticut, to 15 1968: Still swims in Atlantic at age 79 near longtime Babylon, clerk for a silk importer; lodges in Long Island, home Brooklyn Heights 2 1848–55: On 125 acres jane jacobs (born Jane Butzner, 1916–2006) purchased for him by his father, 1 1934: Arrives from Scranton, builds Tosomock Farm into a PA, at age 18, intent on breaking successful nursery between stints into journalism, and with her traveling sister soon moves to the West 3 February 16, 1853: Publishes Village, their “ideal neighbor- first dispatch from the South in hood” Hudson River nascent New York Times, starting 6 5 2 7 1943: Having dropped out a series that transforms him into a staunch abolitionist, respected of Columbia’s University Exten- Riverside 4 journalist, and influential public voice Triborough Park sion, rejecting formal education, Bridge 4 Fall 1857–April 1858: Spending nights at architect Calvert Vaux’s, takes job as writer at the US collaborates -

Norris Dam: to Build Or Not to Build? a Museum Outreach Program Jeanette Patrick James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Norris Dam: To build or not to build? A museum outreach program Jeanette Patrick James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Other Education Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Patrick, Jeanette, "Norris Dam: To build or not to build? A museum outreach program" (2015). Masters Theses. 44. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/44 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Norris Dam: To Build or Not to Build? A Museum Outreach Program Jeanette Patrick A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2015 Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without all of the support I received throughout. I would like to thank my family and friends; while I chose to immerse myself in Norris Dam and the Tennessee Valley Authority, they were all wonderful sports as I pulled them down the river from one dam project to the next. Additionally, I do not believe I would have made it through the past two years without my peers. Their support and camaraderie helped me grow not only as a historian but as a person. -

Natural Resources

Natural Heritage in the MSNHA The Highland Rim The Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area is located within the Highland Rim section of Alabama. The Highland Rim is the southernmost section of a series low plateaus that are part of the Appalachian Mountains. The Highland Rim is one of Alabama’s five physiographic regions, and is the smallest one, occupying about 7 percent of the state. The Tennessee River The Tennessee River is the largest tributary off the Ohio River. The river has been known by many names throughout its history. For example, it was known as the Cherokee River, because many Cherokee tribes had villages along the riverbank. The modern name of the river is derived from a Cherokee word tanasi, which means “river of the great bend.” The Tennessee River has many dams on it, most of them built in the 20th century by the Tennessee Valley Authority. Due to the creation of these dams, many lakes have formed off the river. One of these is Pickwick Lake, which stretches from Pickwick Landing Dam in Tennessee, to Wilson Dam in the Shoals area. Wilson Lake and Wheeler Lake are also located in the MSNHA. Additionally, Wilson Dam Bear Creek Lakes were created by four TVA constructed dams on Bear Creek and helps manage flood conditions and provides water to residents in North Alabama. Though man-made, these reservoirs have become havens for fish, birds, and plant life and have become an integral part of the natural heritage of North Alabama. The Muscle Shoals region began as port area for riverboats travelling the Tennessee River. -

Tennessee Lesson

TENNESSEE SOCIAL STUDIES LESSON #1 OutOut ofof thethe DarknessDarkness Topic The Tennessee Valley Authority and the Great Depression Introduction The purpose of these lessons is to introduce students to the World• War I and the Roaring Twenties (1920s-1940s) role that the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) • 5.16 Describe how New Deal policies of President Franklin played in the economic development of the South during the D. Roosevelt impacted American society with Depression. The length of these lessons can be adjusted to government-funded programs, including: Social Security, meet your time constraints. Student access to a computer lab expansion and development of the national parks, and with Internet connectivity is recommended but not required. creation of jobs. (C, E, G, H, P) Another option is for the teacher to conduct the lessons in a Tennessee in the 20th Century classroom with one computer with Internet connectivity and an LCD projector. • 5.48 Describe the effects of the Great Depression on Tennessee and the impact of New Deal policies in the state (i.e., Tennessee Valley Authority and Civilian Conservation Tennessee Curriculum Standards Corps). (C, E, G, H, P, T) These lessons help fulfill the following Tennessee Teaching Standards for: Primary Documents and Supporting Texts The 1920s • Franklin Roosevelt’s First Inaugural Address • Political cartoons about the New Deal • US.31 Describe the impact of new technologies of the era, including the advent of air travel and spread of electricity. (C, E, H) Objectives The Great Depression and New Deal • Students will identify New Deal Programs/Initiatives (TVA). -

Unions and Party Politics on Long Island Party by Exchanging Jobs, Contracts and Positions for Votes

LABOR HISTORY stronghold for the Democratic Unions and Party Politics on Long Island Party by exchanging jobs, contracts and positions for votes. by Lillian Dudkiewicz-Clayman The city Democratic machine has been long-lasting. Even today, despite the election of Republicans LaGuardia, Lindsay, Giuliani and hese are interesting times for Long Island labor unions. Many of the current union leaders and activists on Long Island Bloomberg as mayors, the Almost every day, newspapers are filled with stories about were born and raised in working class families that moved to Long Democratic Party is still dominant. Tone level of government or the other looking to balance their Island from one of New York City’s five boroughs. Most have In 2012, in most of the New York budgets by laying off workers, cutting the benefits of organized stayed true to their working class roots. As they and their families City council districts, and in most workers or negotiating givebacks. On May 21, 2012, the Republican- moved to the Island, they regularly enrolled as Republicans. Their of the city’s state assembly and dominated Nassau County legislature proposed a bill that would, in unions, with only a few exceptions, supported Republican state senate districts, the primary effect, completely undermine collective bargaining. This happened candidates. This occurred despite the fact that over the years since election for the Democratic at the end of their legislative session after it had been announced WWII, the national Republican Party was the party that took nomination is viewed by many as that the bill would be tabled. -

Bank Fishing

Bank Fishing The following bank fishing locations were compiled by 4. Fish are very sensitive to sounds and shadows and can TWRA staff to inform anglers of areas where you can fish see and hear an angler standing on the bank. It is good without a boat. The types of waters vary from small ponds to fish several feet back from the water’s edge instead and streams to large reservoirs. You might catch bluegill, of on the shoreline and move quietly, staying 20 to 30 bass, crappie, trout, catfish, or striped bass depending on feet away from the shoreline as you walk (no running) the location, time of year, and your skill or luck. from one area to the other. Point your rod towards the All waters are open to the public. Some locations are sky when walking. Wearing clothing that blends in privately owned and operated, and in these areas a fee is re- with the surroundings may also make it less likely for quired for fishing. It is recommended that you call ahead if fish to be spooked. you are interested in visiting these areas. We have included 5. Begin fishing (casting) close and parallel to the bank these fee areas, because many of them they are regularly and then work out (fan-casting) toward deeper water. stocked and are great places to take kids fishing. If you’re fishing for catfish, keep your bait near the bottom. Look around for people and obstructions Bank Fishing Tips before you cast. 1. Fish are often near the shore in the spring and fall.