Orchard Beach Bathhouse and Promenade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2021 Resources

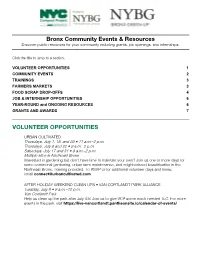

Bronx Community Events & Resources Discover public resources for your community including grants, job openings, and internships. Click the title to jump to a section. VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES 1 COMMUNITY EVENTS 2 TRAININGS 3 FARMERS MARKETS 3 FOOD SCRAP DROP-OFFS 4 JOB & INTERNSHIP OPPORTUNITIES 6 YEAR-ROUND and ONGOING RESOURCES 6 GRANTS AND AWARDS 7 VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES URBAN CULTIVATED Thursdays, July 1, 15, and 29 • 11 a.m.–2 p.m. Thursdays, July 8 and 22 • 9 a.m.–2 p.m. Saturdays, July 17 and 31 • 9 a.m.–2 p.m. Multiple sites in Northeast Bronx Interested in gardening but don’t have time to maintain your own? Join us one or more days for some communal gardening, urban farm maintenance, and neighborhood beautification in the Northeast Bronx. Training provided. To RSVP or for additional volunteer days and times, email [email protected] AFTER HOLIDAY WEEKEND CLEAN UPS • VAN CORTLANDT PARK ALLIANCE Tuesday, July 6 • 9 a.m.–12 p.m. Van Cortlandt Park Help us clean up the park after July 4th! Join us to give VCP some much needed TLC. For more events in the park, visit https://live-vancortlandt.pantheonsite.io/calendar-of-events/ COMMUNITY VOLUNTEERS TO HELP WITH SYEP • FRIENDS OF MOSHOLU PARKLAND 6 weeks, July 6–August 13 • 8 a.m.–1 p.m. Mosholu Parkland • 3400 Reservoir Oval East Guide students to help clean up Mosholu Parkland, our six playgrounds, and the Keepers House Edible Garden. Tasks include painting pillars and benches, mulching walking paths, tree pit care, weeding, groundskeeping, helping at community gardens, and more. -

2020 New York No Numbers

NEW YORK, NEW YORK A list celebrating the city that – until last month – never sleeps. These 50 selections reflect the city’s important contributions to history, art, music, literature, cuisine, engineering, transportation, architecture, and leisure. This is an enhanced PDF catalog. If you click on an image or the highlighted headline of any entry, you will be linked to our website where you will find images. We are happy to provide more images or information upon request. In chronological order 1. HARDIE, James. The Description of the City of New York. New York: Samuel Marks, 1827. 8vo. 360 pages. Hand-colored engraved folding map. Contemporary sheep, gilt decorated on spine. Provenance: contemporary ownership inscription on front free endpaper. Binding worn, occasional pale spotting. Large folding map has a small tear at the attachment else very clean and bright. $325 FIRST EDITION. Church 1336; Howes H-184. Sabin 30319. RIVERRUN BOOKS & MANUSCRIPTS NEW YORK HYDRATED 2. RENWICK, James. Report on the Water Power at Kingsbridge near the City of New-York, Belonging to New- York Hydraulic Manufacturing and Bridge Company. New-York: Samuel Marks, 1827. 8vo. 12 pages. Three folding lithographed maps, printed by Imbert. Sewn in original printed wrappers, untrimmed; blue cloth portfolio. Provenance: contemporary signature on front wrapper of D. P. Campbell at 51 Broadway. Wear to wrappers, some light foxing, maps clean and bright. $1,200 FIRST EDITION of this scarce pamphlet on the development of the New York water supply. Renwick was Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy and Chemistry at Columbia College, and writes at the request of the directors of the New York Hydraulic Manufacturing and Bridge Company who asked him to examine their property at Kingsbridge. -

Water Quality Featuring Brett Branco (BB) Hosted by Helen Cheng

Episode 2: Water Quality Featuring Brett Branco (BB) Hosted by Helen Cheng (HC) Air Date: May 2017 Animals need it and people too; water, water everywhere. But is its quality that we are aware? Welcome to Jamaica Bay. -Music interlude- You’re listening to Jamaica Bay, a podcast series bringing you stories of the people that work, live, and play in Jamaica Bay, New York City. I’m your host, Helen Cheng. And I’m from the Science and Resilience Institute at Jamaica Bay and New York Sea Grant. -Music interlude- Beyond the skyscrapers and the masses of people, you might not realize it at first but New York City is more than just a booming metropolis. BB: “Well, New York City is an island. Manhattan obviously and Staten Island obviously, but even Brooklyn and Queens are part of Long Island. And we’re a coastal city so we’re intimately tied to the waters.” To learn about the New York City waters and Jamaica Bay waters, I sat down with BB: “Brett Branco, I’m a professor here at Brooklyn College, also hold a joint appointment at the CUNY Graduate Center. I’m also currently the director of the Urban Sustainability Program here at Brooklyn College.” Brett does research on shallow, coastal, and inland waters. A lot of his research looks at human impacts on estuaries and coasts especially in New York City bodies like Jamaica Bay. In particular, he’s looking at the water quality of Jamaica Bay. HC: “What is water quality and why is it important?” BB: “Yea, that’s sort of people’s favorite questions to me. -

Ger.* One of the Common Beliefs of Lawyers, and Particularly of Aca- Demic Lawyers, Is That We Can Save the World Through the Processes of Law

THE POWER BROKER: ROBERT MOSES AND THE FALL OF NEW YORK. By Robert A. Caro. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974. Pp. 1246. Clothbound $17.95. Paperbound $7.95. Reviewed by Peter D. Jun- ger.* One of the common beliefs of lawyers, and particularly of aca- demic lawyers, is that we can save the world through the processes of law. This belief is a source of comfort, and perhaps of inspiration, to the profession, but there is some reason to wonder just how great an impact "law" does have in really shaping events when confronted by big questions-or big men. The story unfolded in Robert Caro's book, The Power Broker, Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, offers a case in point. Caro is not a lawyer, and therefore perhaps not a firm believer in the efficacy of law. He is a journalist, mesmerized by the rising and falling of New York and of that shadowy colossus, Robert Moses. As a result, he is able to expose, within his mosaic of a decaying city, not only the stork ornamenting the bathouse of Corona Pool "wearing an expression that made him look as if he were puz- zling over the physical differences in the creatures he had brought into the world,"' but also a paradigm of our most troubling problem, the irrational structure of our policy. Caro, the reporter, stands at the opposite pole from most legal writers and some of the political scien- tists. He supplies us, not with principles and definitions, but with a mass of facts of the sort that resist quantification. -

Departmentof Parks

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS BOROUGH OF THE BRONX CITY OF NEW YORK JOSEPH P. HENNESSY, Commissioner HERALD SQUARE PRESS NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH OF 'I'HE BRONX January 30, 1922. Hon. John F. Hylan, Mayor, City of New York. Sir : I submit herewith annual report of the Department of Parks, Borough of The Bronx, for 1921. Respect fully, ANNUAL REPORT-1921 In submitting to your Honor the report of the operations of this depart- ment for 1921, the last year of the first term of your administration, it will . not be out of place to review or refer briefly to some of the most important things accomplished by this department, or that this department was asso- ciated with during the past 4 years. The very first problem presented involved matters connected with the appropriation for temporary use to the Navy Department of 225 acres in Pelham Bay Park for a Naval Station for war purposes, in addition to the 235 acres for which a permit was given late in 1917. A total of 481 one- story buildings of various kinds were erected during 1918, equipped with heating and lighting systems. This camp contained at one time as many as 20,000 men, who came and went constantly. AH roads leading to the camp were park roads and in view of the heavy trucking had to be constantly under inspection and repair. The Navy De- partment took over the pedestrian walk from City Island Bridge to City Island Road, but constructed another cement walk 12 feet wide and 5,500 feet long, at the request of this department, at an expenditure of $20,000. -

Weymouth Centered on Literature and Hunting That Continued up to James Boyd’S Death in 1944

Cultural Landscape Report for Weymouth Southern Pines, NC Davyd Foard Hood Landscape Historian & Glenn Thomas Stach Preservation Landscape Architect August 2011 Cultural Landscape Report for Weymouth Southern Pines, NC August 2011 Client: Town of Southern Pines This study was funded in part from the Historic Preservation Fund grant from the U.S. National Park Service through the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, with additional funding and support by the Southern Pines Garden Club Preparers: Davyd Foard Hood, Landscape Historian Glenn Thomas Stach, Preservation Landscape Architect Table of Contents List of Figures & Plans Introduction…………………………………………………………………….…….….…….viii Chapter I: History Narrative & Supporting Imagery………………………….….……I-1 thru 61 Chapter II: Existing Conditions & Supporting Imagery ………..…………....………II-1 thru 23 Chapter III: Analysis & Evaluation with Supporting Imagery……………………….III1 thru 20 Appendix A: Period, Existing, and Analysis Plans and Diagrams Appendix B: Boyd Family Genealogical Table Appendix C: Floor Plans Appendix D. Street Map of Southern Pines Weymouth Cultural Landscape Report List of Figures Chapter I I/1 View of Weymouth, looking southwest along the brick lined path in the lower terrace, showing plantings along the path by students in the Sandhills horticultural program launched in 1968, the cold frame, and dense shrub plantings in the lower terrace, the tall Japanese privet hedge separating the upper and lower terraces, and the manner by which Alfred B. Yeomans closed the axial view with the corner of the loggia in his ca. 1932 addition, ca. 1970. Weymouth Archives. I/2 Photograph of James Boyd, seated, ca. 1890‐1900, Weymouth Archives. I/3 Hand‐colored postal view, “Vermont Avenue, Southern Pines, N.C.”, by E. -

New Facilities in a Post-Industrial Texas Landscape Welcomes

New facilities in a postindustrial Texan landscape welcomes migratory birds—and onlookers ARCHITECTURE ART DESIGN URBANISM AN INTERIOR AWARDS EVENTS SUBSCRIBE Top Flight New facilities in a postindustrial Texan landscape welcomes migratory birds—and onlookers By Lila Allen • June 16, 2021 • Architecture, News, Southwest, Sustainability On High Island, a new, elevated 700-square-foot long canopy walkway, designed by SWA Group and SCHAUM/SHIEH, weaves through the 177-acre site, allowing visitors birds-eye views of the surrounding flora and fauna. (Jonnu Singleton/Courtesy SWA Group) SHARE At rst blush, High Island, Texas, sounds downright dystopian. A site of 20th-century oil extraction, the landscape has as its dening feature a massive salt dome—a pimple-like swell rising 38 feet above sea level. Located on the eastern side of Galveston Bay, just inland from the Gulf of Mexico, High Island is prone to destrucNteivwe fhaucirlritiiceasn iens a a pnods atilnsodu hsatrsi athl Tee dxuanb iloaunsd sdcistapine cwteiolcno omfes migratory birds—and onlookers being a burial ground for the serial killer Dean Corll. But for some, High Island is a haven: each spring, the site welcomes thousands of migratory birds on their northward journey from Mexico that are drawn to the freshwater reservoirs and local ora. Ten thousand birders ock to High Island’s bird sanctuaries annually, including Smith Oaks, a 177-acre site operated by the Houston Audubon Society. Now that site is better equipped to welcome them, thanks to the introduction of a 700- foot-long canopy walkway and support facilities from architects SWA Group and SCHAUM/SHIEH. -

Fresh Kills Dumped : a Policy Assessment for the Management of New York City's Residential Solid Waste in the Twenty-First Century

New Jersey Institute of Technology Digital Commons @ NJIT Theses Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-31-2003 Fresh kills dumped : a policy assessment for the management of New York City's residential solid waste in the twenty-first century Aaron William Comrov New Jersey Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.njit.edu/theses Part of the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Comrov, Aaron William, "Fresh kills dumped : a policy assessment for the management of New York City's residential solid waste in the twenty-first century" (2003). Theses. 615. https://digitalcommons.njit.edu/theses/615 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ NJIT. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ NJIT. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright Warning & Restrictions The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a, user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use” that user may be liable for copyright infringement, This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

“Forgotten by God”: How the People of Barren Island Built a Thriving Community on New York City's Garbage

“Forgotten by God”: How the People of Barren Island Built a Thriving Community on New York City’s Garbage ______________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Brooklyn College ______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Miriam Sicherman Thesis Advisor: Michael Rawson Spring 2018 Table of Contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgments 2 Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Early History, Landscape, and Population 22 Chapter 2: Outsiders and Insiders 35 Chapter 3: Work 53 Chapter 4: Recreation and Religion 74 Chapter 5: Municipal Neglect 84 Chapter 6: Law and Order 98 Chapter 7: Education 112 Chapter 8: The End of Barren Island 134 Conclusion 147 Works Cited 150 1 Abstract This thesis describes the everyday life experiences of residents of Barren Island, Brooklyn, from the 1850s until 1936, demonstrating how they formed a functioning community under difficult circumstances. Barren Island is located in Jamaica Bay, between Sheepshead Bay and the Rockaway Peninsula. During this time period, the island, which had previously been mostly uninhabited, was the site of several “nuisance industries,” primarily garbage processing and animal rendering. Because the island was remote and often inaccessible, the workers, mostly new immigrants and African-Americans, were forced to live on the island, and very few others lived there. In many ways the islanders were neglected and ignored by city government and neighboring communities, except as targets of blame for the bad smells produced by the factories. In the absence of adequate municipal attention, islanders were forced to create their own community norms and take care of their own needs to a great extent. -

To Download Three Wonder Walks

Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) Featuring Walking Routes, Collections and Notes by Matthew Jensen Three Wonder Walks (After the High Line) The High Line has proven that you can create a des- tination around the act of walking. The park provides a museum-like setting where plants and flowers are intensely celebrated. Walking on the High Line is part of a memorable adventure for so many visitors to New York City. It is not, however, a place where you can wander: you can go forward and back, enter and exit, sit and stand (off to the side). Almost everything within view is carefully planned and immaculately cultivated. The only exception to that rule is in the Western Rail Yards section, or “W.R.Y.” for short, where two stretch- es of “original” green remain steadfast holdouts. It is here—along rusty tracks running over rotting wooden railroad ties, braced by white marble riprap—where a persistent growth of naturally occurring flora can be found. Wild cherry, various types of apple, tiny junipers, bittersweet, Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, mullein, Indian hemp, and dozens of wildflowers, grasses, and mosses have all made a home for them- selves. I believe they have squatters’ rights and should be allowed to stay. Their persistence created a green corridor out of an abandoned railway in the first place. I find the terrain intensely familiar and repre- sentative of the kinds of landscapes that can be found when wandering down footpaths that start where streets and sidewalks end. This guide presents three similarly wild landscapes at the beautiful fringes of New York City: places with big skies, ocean views, abun- dant nature, many footpaths, and colorful histories. -

Tomorrow's World

Tomorrow’s World: The New York World’s Fairs and Flushing Meadows Corona Park The Arsenal Gallery June 26 – August 27, 2014 the “Versailles of America.” Within one year Tomorrow’s World: 10,000 trees were planted, the Grand Central Parkway connection to the Triborough Bridge The New York was completed and the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge well underway.Michael Rapuano’s World’s Fairs and landscape design created radiating pathways to the north influenced by St. Peter’s piazza in the Flushing Meadows Vatican, and also included naturalized areas Corona Park and recreational fields to the south and west. The Arsenal Gallery The fair was divided into seven great zones from Amusement to Transportation, and 60 countries June 26 – August 27, 2014 and 33 states or territories paraded their wares. Though the Fair planners aimed at high culture, Organized by Jonathan Kuhn and Jennifer Lantzas they left plenty of room for honky-tonk delights, noting that “A is for amusement; and in the interests of many of the millions of Fair visitors, This year marks the 50th and 75th anniversaries amusement comes first.” of the New York World’s Fairs of 1939-40 and 1964-65, cultural milestones that celebrated our If the New York World’s Fair of 1939-40 belonged civilization’s advancement, and whose visions of to New Dealers, then the Fair in 1964-65 was for the future are now remembered with nostalgia. the baby boomers. Five months before the Fair The Fairs were also a mechanism for transform- opened, President Kennedy, who had said, “I ing a vast industrial dump atop a wetland into hope to be with you at the ribbon cutting,” was the city’s fourth largest urban park. -

2196 Astoria Park Pool And

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 20, 2006, Designation List 377 LP- 2196 ASTORIA PARK POOL AND PLAY CENTER, including the bath house, wading pool, diving pool, filter house, bleachers, brick perimeter walls, piers and cast iron fencing, stairways to bath house roof-top observation decks, comfort station, and connecting pathways, 19th Street between 22nd Drive and Hoyt Avenue North, Astoria Park, Borough of Queens. Constructed 1934-36; John M. Hatton and others, Architects; Aymar Embury II, Consulting Architect; Gilmore D. Clarke and others, Landscape Architects. Landmark Site: Tax Map Block 898, Lot 1 in part, and portions of the adjacent public way, consisting of the property bounded by a line extending northerly from a point defined by the intersection of the western curbline or 19th Street and the northern curbline of Hoyt Avenue North (where it extends westerly to form the vehicular entrance to the Astoria Park parking lot), along the western curbline of 19th Street to a line extending easterly from the line of the southernmost wall of the Hellgate Bridge anchorage, continuing westerly along that line and the line of the southernmost wall of the Hellgate Bridge anchorage to the U.S. Pierhead and Bulkhead Line, then southerly along the U.S. Pierhead and Bulkhead Line to a line extending westerly from the line of the northernmost wall of the Triborough Bridge anchorage, then easterly along that line to the western concrete curb of the concrete and asphalt Astoria Park parking lot, continuing northeasterly, then southeasterly around the curvature of the concrete curb to the point of the beginning.