Robert Moses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 24, 2009, Designation List 411 LP-2311 NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN MUSEUM

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 24, 2009, Designation List 411 LP-2311 NEW YORK BOTANICAL GARDEN MUSEUM (now LIBRARY) BUILDING, FOUNTAIN OF LIFE, and TULIP TREE ALLEE, Watson Drive and Garden Way, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx Park, the Bronx; Museum Building designed 1896, built 1898-1901, Robert W. Gibson, architect; Fountain 1901-05, Carl (Charles) E. Tefft, sculptor, Gibson, architect; Allee planted 1903-11. Landmark Site: Borough of the Bronx Tax Map 3272, Lot 1 in part, consisting of the property bounded by a line that corresponds to the outermost edges of the rear (eastern) portion of the original 1898-1901 Museum (now Library) Building (excluding the International Plant Science Center, Harriet Barnes Pratt Library Wing, and Jeannette Kittredge Watson Science and Education Building), the southernmost edge of the original Museum (now Library) Building (excluding the Annex) and a line extending southwesterly to Garden Way, the eastern curbline of Garden Way to a point on a line extending southwesterly from the northernmost edge of the original Museum (now Library) Building, and northeasterly along said line and the northernmost edge of the original Museum (now Library) Building, to the point of beginning. On October 28, 2008, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the New York Botanical Garden Museum (now Library) Building, Fountain of Life, and Tulip Tree Allee and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Six people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the New York Botanical Garden, Municipal Art Society of New York, Historic Districts Council, Metropolitan Chapter of the Victorian Society in America, and New York Landmarks Conservancy. -

S T a T E O F N E W Y O R K 3695--A 2009-2010

S T A T E O F N E W Y O R K ________________________________________________________________________ 3695--A 2009-2010 Regular Sessions I N A S S E M B L Y January 28, 2009 ___________ Introduced by M. of A. ENGLEBRIGHT -- Multi-Sponsored by -- M. of A. KOON, McENENY -- read once and referred to the Committee on Tourism, Arts and Sports Development -- recommitted to the Committee on Tour- ism, Arts and Sports Development in accordance with Assembly Rule 3, sec. 2 -- committee discharged, bill amended, ordered reprinted as amended and recommitted to said committee AN ACT to amend the parks, recreation and historic preservation law, in relation to the protection and management of the state park system THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, REPRESENTED IN SENATE AND ASSEM- BLY, DO ENACT AS FOLLOWS: 1 Section 1. Legislative findings and purpose. The legislature finds the 2 New York state parks, and natural and cultural lands under state manage- 3 ment which began with the Niagara Reservation in 1885 embrace unique, 4 superlative and significant resources. They constitute a major source of 5 pride, inspiration and enjoyment of the people of the state, and have 6 gained international recognition and acclaim. 7 Establishment of the State Council of Parks by the legislature in 1924 8 was an act that created the first unified state parks system in the 9 country. By this act and other means the legislature and the people of 10 the state have repeatedly expressed their desire that the natural and 11 cultural state park resources of the state be accorded the highest 12 degree of protection. -

Professionals on Review: an Historic Profile of the 98Th "Iroquois" Division

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Foreword . ........ .............................. ...................... 1 Introduction ............................................. ................. 2 Division Mission ........................................................... 3 Division History ......................................................... 4-12 389th Regiment ...................... ................................ 13 390th Regiment .................................................... 14-15 391stRegiment .................................................... 16-17 392nd Regiment .........•.. .................... ................. 18-19 Combat Engineers ................................................. 20-21 Communicators ................................................... 22-23 Providers . ............ ........... ....... ....................... 24-25 Civil Affairs Companies ...................... ........... ............. 26 Army Reserve Schools ......................... ....... .. ........... 27 Cased Colors ...................................................... 28-30 Former Division Commanders ............................................. 31 Division Today- Division Command and Staff ........................................... 32 Major Subordinate Commanders ........ .............................. 33 Units and Locations ............................•...... .............. 34-35 Acknowledgements ............................................... ....... 37 Foreword by MAJOR GENERAL CHARLES D. BARRETT Commander, 98th Division (Training) Prepared, proud, -

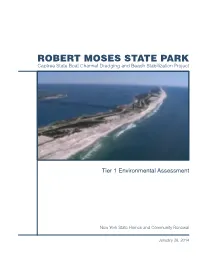

ROBERT MOSES STATE PARK Captree State Boat Channel Dredging and Beach Stabilization Project

ROBERT MOSES STATE PARK Captree State Boat Channel Dredging and Beach Stabilization Project Tier 1 Environmental Assessment New York State Homes and Community Renewal January 29, 2014 Robert Moses State Park Captree State Boat Channel Dredging and Beach Stabilization Project Tier 1 Environmental Assessment January 29, 2014 Project Name: Robert Moses State Park State Boat Channel Dredging and Beach Stabilization Project Project Location: Robert Moses State Park, Towns of Babylon and Islip, Suffolk County, NY HTFC SHARS #: N/A Federal Agency: US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Responsible Entity: New York State Homes and Community Renewal (HCR) Responsible Agency’s Certifying Officer: Heather Spitzberg, HCR Environmental Analysis Unit Project Sponsor: New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (OPRHP) Primary Contact: Mr. Marc Talluto, Director of Operations New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation 625 Broadway Albany, NY 12207 [email protected] (518) 474-0440 Project NEPA Classification: 24 CFR 58.36 (Environmental Assessment) Environmental Finding: Finding of No Significant Impact - The project will not result in a significant impact on the quality of the human environment. Finding of Significant Impact - The project may significantly affect the quality of the human environment. The undersigned hereby certifies that HCR has conducted an environmental review of the project identified above and prepared the attached environmental review record in compliance with all applicable provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended (42 USC Sec. 4321 et seq.) and its implementing regulations at 24 CFR Part 58. Heather Spitzberg Environmental Assessment Prepared By: AKRF, Inc. -

Oral History Interview with Pietro Lazzari, 1964

Oral history interview with Pietro Lazzari, 1964 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview HP: DR. HARLAN PHILLIPS PL: PIETRO LAZZARI HP: I think while we have the opportunity it's, I think, important to assess in a way what one begins with. You have at least, you know, a dual cultural view, more, probably, so what did you fall heir to in the way of luggage and baggage that you've carried? PL: Well, I do believe I was quite lucky, if we can put it this way, I was born in the last century, 1898, in Rome and not from a family were cultural marked point was strong. My father was very inventive himself, he could draw horses. He loved to walk long distances. I remember as a young boy we used to walk outside the gates of Rome in Via Solaria or toward Ostia, and he was not a very tall man but while he walked, and while he talked he grew, I thought he was very tall, and he was inspired, his chest forward because he was the bandolier, which is a sort of an elite corps in the Italian army and he volunteered very young. So going back to our walks, he was familiar with the Roman ruins and frescoes in churches particularly those churches on the outskirts of Rome. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

JULY 2017 WELCOME MIKE HAUSBERG Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of King Richard II. Our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. IMPACT Our prominence nationally and locally brings with it a responsibility to listen, collaborate, and act with integrity in order to serve. -

Ger.* One of the Common Beliefs of Lawyers, and Particularly of Aca- Demic Lawyers, Is That We Can Save the World Through the Processes of Law

THE POWER BROKER: ROBERT MOSES AND THE FALL OF NEW YORK. By Robert A. Caro. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974. Pp. 1246. Clothbound $17.95. Paperbound $7.95. Reviewed by Peter D. Jun- ger.* One of the common beliefs of lawyers, and particularly of aca- demic lawyers, is that we can save the world through the processes of law. This belief is a source of comfort, and perhaps of inspiration, to the profession, but there is some reason to wonder just how great an impact "law" does have in really shaping events when confronted by big questions-or big men. The story unfolded in Robert Caro's book, The Power Broker, Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, offers a case in point. Caro is not a lawyer, and therefore perhaps not a firm believer in the efficacy of law. He is a journalist, mesmerized by the rising and falling of New York and of that shadowy colossus, Robert Moses. As a result, he is able to expose, within his mosaic of a decaying city, not only the stork ornamenting the bathouse of Corona Pool "wearing an expression that made him look as if he were puz- zling over the physical differences in the creatures he had brought into the world,"' but also a paradigm of our most troubling problem, the irrational structure of our policy. Caro, the reporter, stands at the opposite pole from most legal writers and some of the political scien- tists. He supplies us, not with principles and definitions, but with a mass of facts of the sort that resist quantification. -

Donor-Advised Fund

WELCOME. The New York Community Trust brings together individuals, families, foundations, and businesses to support nonprofits that make a difference. Whether we’re celebrating our commitment to LGBTQ New Yorkers—as this cover does—or working to find promising solutions to complex problems, we are a critical part of our community’s philanthropic response. 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 1 A WORD FROM OUR DONORS Why The Trust? In 2018, we asked our donors, why us? Here’s what they said. SIMPLICITY & FAMILY, FRIENDS FLEXIBILITY & COMMUNITY ______________________ ______________________ I value my ability to I chose The Trust use appreciated equities because I wanted to ‘to‘ fund gifts to many ‘support‘ my community— different charities.” New York City. My ______________________ parents set an example of supporting charity My accountant and teaching me to save, suggested The Trust which led me to having ‘because‘ of its excellent appreciated stock, which tools for administering I used to start my donor- donations. Although advised fund.” my interest was ______________________ driven by practical considerations, The need to fulfill the I eventually realized what charitable goals of a dear an important role it plays ‘friend‘ at the end of his life in the City.” sent me to The Trust. It was a great decision.” ______________________ ______________________ The Trust simplified our charitable giving.” Philanthropy is a ‘‘ family tradition and ______________________ ‘priority.‘ My parents communicated to us the A donor-advised fund imperative, reward, and at The Trust was the pleasure in it.” ‘ideal‘ solution for me and my family.” ______________________ I wanted to give back, so I opened a ‘fund‘ in memory of my grandmother and great-grandmother.” 2 NYCOMMUNITYTRUST. -

Bibliography Abram - Michell

Landscape Design A Cultural and Architectural History 1 Bibliography Abram - Michell Surveys, Reference Books, Philosophy, and Nikolaus Pevsner. The Penguin Dictionary Nancy, Jean-Luc. Community: The Inoperative Studies in Psychology and the Humanities of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Community. Edited by Peter Connor. Translated 5th ed. London: Penguin Books, 1998. by Peter Connor, Lisa Garbus, Michael Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Holland, and Simona Sawhney. Minneapolis: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human Foucault, Michel. The Order of Being: University of Minnesota Press, 1991. World. New York: Pantheon Books, 1996. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Translated by [tk]. New York: Vintage Books, Newton, Norman T. Design on the Land: Ackerman, James S. The Villa: Form and 1994. Originally published as Les Mots The Development of Landscape Architecture. Ideology of Country Houses. Princeton, et les choses (Paris: Gallimard, 1966). Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971. N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1990. Giedion, Sigfried. Space, Time and Architecture. Ross, Stephanie. What Gardens Mean. Chicago Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967. and London: University of Chicago Press, 1998. Space. Translated by Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press, 1969. Gothein, Marie Luise. Translated by Saudan, Michel, and Sylvia Saudan-Skira. Mrs. Archer-Hind. A History of Garden From Folly to Follies: Discovering the World of Barthes, Roland. The Eiffel Tower and Other Art. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1928. Gardens. New York: Abbeville Press. 1988. Mythologies. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979. Hall, Peter. Cities in Civilization: Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. The City as Cultural Crucible. -

Weymouth Centered on Literature and Hunting That Continued up to James Boyd’S Death in 1944

Cultural Landscape Report for Weymouth Southern Pines, NC Davyd Foard Hood Landscape Historian & Glenn Thomas Stach Preservation Landscape Architect August 2011 Cultural Landscape Report for Weymouth Southern Pines, NC August 2011 Client: Town of Southern Pines This study was funded in part from the Historic Preservation Fund grant from the U.S. National Park Service through the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, with additional funding and support by the Southern Pines Garden Club Preparers: Davyd Foard Hood, Landscape Historian Glenn Thomas Stach, Preservation Landscape Architect Table of Contents List of Figures & Plans Introduction…………………………………………………………………….…….….…….viii Chapter I: History Narrative & Supporting Imagery………………………….….……I-1 thru 61 Chapter II: Existing Conditions & Supporting Imagery ………..…………....………II-1 thru 23 Chapter III: Analysis & Evaluation with Supporting Imagery……………………….III1 thru 20 Appendix A: Period, Existing, and Analysis Plans and Diagrams Appendix B: Boyd Family Genealogical Table Appendix C: Floor Plans Appendix D. Street Map of Southern Pines Weymouth Cultural Landscape Report List of Figures Chapter I I/1 View of Weymouth, looking southwest along the brick lined path in the lower terrace, showing plantings along the path by students in the Sandhills horticultural program launched in 1968, the cold frame, and dense shrub plantings in the lower terrace, the tall Japanese privet hedge separating the upper and lower terraces, and the manner by which Alfred B. Yeomans closed the axial view with the corner of the loggia in his ca. 1932 addition, ca. 1970. Weymouth Archives. I/2 Photograph of James Boyd, seated, ca. 1890‐1900, Weymouth Archives. I/3 Hand‐colored postal view, “Vermont Avenue, Southern Pines, N.C.”, by E. -

Current, August 22, 2005

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2000s) Student Newspapers 8-22-2005 Current, August 22, 2005 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2000s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, August 22, 2005" (2005). Current (2000s). 261. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2000s/261 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2000s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 38 Aug. 22, 2005 ISSUE 1156 Your source for campus news and information See page 7 Greeks get ready for rush THECURRENTONUNLCOM -------------____________________________________ UNIVIRSITY OF MISSOURI - ST. lOUIS Floyd hits the road with fixed tuition proposal UM President receives positive but skeptical response BY PAUL HACKBARTH UM tuition increases 2001-2006 News Editor 19.8% MARCELINE, Mo. - In Walt 20 Disney's hometown, Anne Cordray, a single parent of two, is worried about 14.8% the costs of sending her oldest daugh ter to college. Tuesday night, she came to hear UM President Elson Floyd discuss his proposal to guaran tee a fixed tuition rate for two to five years for new students. Cordray's daughter, Whitney, is a senior in high school and hopes to attend college in Missouri this time next year. Cordray and her daughter are looking at different schools, decid ing on which one is best for them, both academically and financially. Floyd has been traveling across the Source: Memo from President Floyd to Board of Curators, June 15, 2005 state in an effort to hear Missourians' views on the tuition freeze. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p.