2020 Report, “Planning Together,”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-2019 Voter Analysis Report

20182019 VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT APRIL 2019 NEW YORK CITY CAMPAIGN FINANCE BOARD Board Chair Frederick P. Schaffer Board Members Gregory T. Camp Richard J. Davis Marianne Spraggins Naomi B. Zauderer Amy M. Loprest Executive Director Roberta Maria Baldini Assistant Executive Director for Campaign Finance Administration Kitty Chan Chief of Staff Daniel Cho Assistant Executive Director for Candidate Guidance and Policy Eric Friedman Assistant Executive Director for Public Affairs Hillary Weisman General Counsel THE VOTER ASSISTANCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE VAAC Chair Naomi B. Zauderer Members Daniele Gerard Joan P. Gibbs Okwudiri Onyedum Arnaldo Segarra Mazeda Akter Uddin Jumaane Williams New York City Public Advocate (Ex-Officio) Michael Ryan Executive Director, New York City Board of Elections (Ex-Officio) The VAAC advises the CFB on voter engagement and recommends legislative and administrative changes to improve NYC elections. 2018–2019 VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT TEAM Lead Editor Gina Chung, Production Editor Lead Writer and Data Analyst Katherine Garrity, Policy and Data Research Analyst Design and Layout Winnie Ng, Art Director Jennifer Sepso, Designer Maps Jaime Anno, Data Manager WELCOME FROM THE VOTER ASSISTANCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE In this report, we take a look back at the past year and the accomplishments and challenges we experienced in our efforts to engage New Yorkers in their elections. Most excitingly, voter turnout and registration rates among New Yorkers rose significantly in 2018 for the first time since 2002, with voters turning out in record- breaking numbers for one of the most dramatic midterm elections in recent memory. Below is a list of our top findings, which we discuss in detail in this report: 1. -

Ger.* One of the Common Beliefs of Lawyers, and Particularly of Aca- Demic Lawyers, Is That We Can Save the World Through the Processes of Law

THE POWER BROKER: ROBERT MOSES AND THE FALL OF NEW YORK. By Robert A. Caro. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974. Pp. 1246. Clothbound $17.95. Paperbound $7.95. Reviewed by Peter D. Jun- ger.* One of the common beliefs of lawyers, and particularly of aca- demic lawyers, is that we can save the world through the processes of law. This belief is a source of comfort, and perhaps of inspiration, to the profession, but there is some reason to wonder just how great an impact "law" does have in really shaping events when confronted by big questions-or big men. The story unfolded in Robert Caro's book, The Power Broker, Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, offers a case in point. Caro is not a lawyer, and therefore perhaps not a firm believer in the efficacy of law. He is a journalist, mesmerized by the rising and falling of New York and of that shadowy colossus, Robert Moses. As a result, he is able to expose, within his mosaic of a decaying city, not only the stork ornamenting the bathouse of Corona Pool "wearing an expression that made him look as if he were puz- zling over the physical differences in the creatures he had brought into the world,"' but also a paradigm of our most troubling problem, the irrational structure of our policy. Caro, the reporter, stands at the opposite pole from most legal writers and some of the political scien- tists. He supplies us, not with principles and definitions, but with a mass of facts of the sort that resist quantification. -

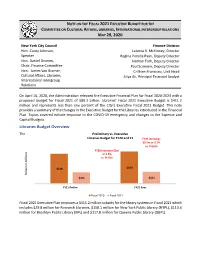

Libraries Budget Overview MAY 29,2020

NOTE ON THE FISCAL 2021 EXECUTIVE BUDGET FOR THE COMMITTEE ON CULTURAL AFFAIRS, LIBRARIES, INTERNATIONAL INTERGROUP RELATIONS MAY 29, 2020 New York City Council Finance Division Hon. Corey Johnson, Latonia R. McKinney, Director Speaker Regina Poreda Ryan, Deputy Director Hon. Daniel Dromm, Nathan Toth, Deputy Director Chair, Finance Committee Paul Scimone, Deputy Director Hon. James Van Bramer, Crilhien Francisco, Unit Head Cultural Affairs, Libraries, Aliya Ali, Principal Financial Analyst International Intergroup Relations On April 16, 2020, the Administration released the Executive Financial Plan for Fiscal 2020-2024 with a proposed budget for Fiscal 2021 of $89.3 billion. Libraries’ Fiscal 2021 Executive Budget is $411.2 million and represents less than one percent of the City’s Executive Fiscal 2021 Budget. This note provides a summary of the changes in the Executive Budget for the Libraries introduced in the Financial Plan. Topics covered include response to the COVID-19 emergency and changes to the Expense and Capital Budgets. Libraries Budget Overview The Preliminary vs. Executive Libraries Budget for FY20 and 21 FY21 increases $0.5m or 0.1% vs. Prelim FY20 increases $2m or 0.5% vs. Prelim $428 $430 Dollars in Millions $411 $411 FY21 Prelim FY21 Exec Fiscal 2020 Fiscal 2021 Fiscal 2021 Executive Plan proposes a $411.2 million subsidy for the library systems in Fiscal 2021 which includes $29.8 million for Research Libraries, $150.1 million for New York Public Library (NYPL), $113.4 million for Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) and $117.8 million for Queens Public Library (QBPL). $410.7 Million Executive Plan $411.2 Million Fiscal 2021 Changes Fiscal 2021 Executive Preliminary • Research Libraries: • New Needs: None • Research Libraries: $30.1M • Other Adjustments: $29.9M • NYPL: $149.6M 458,000 • NYPL: $150.1M • BPL: $113.2M • PEGs: None • BPL: $113.4M • QBPL: $117.8M • QBPL: $117.8M Changes introduced in the Executive Plan increase the Libraries budget for Fiscal 2021 by $500,000. -

The Council of the City of New York Office of Council Member Antonio

The Council of the City of New York Office of Council Member Antonio Reynoso 250 Broadway, Suite 1740 NY, New York 10007 May 10th, 2018 Press Release For Immediate Release Kristina Naplatarski [email protected] (347) 581-2050 (C) (212) 788-7095 (O) Council Member Reynoso, East Brooklyn Congregations, and Metro IAF Call Upon the de Blasio Administration to Build More Affordable Senior Housing on Unutilized NYCHA Land May 10th, 2018 —Bushwick, NY— Today, New York City Council Member Antonio Reynoso in conjunction with East Brooklyn Congregations and Metro IAF called upon the de Blasio administration to build more affordable senior housing on vacant NYCHA land. In Mayor Bill de Blasio’s 2014 “Housing New York” plan, the administration promised to increase the supply of housing for seniors by reaching 15,000 households through a combined effort of new construction and preservation. In 2017, the administration doubled this effort, aiming to serve 30,000 units over an extended 12 year period. The administration has made progress towards this goal; several sites throughout the city, including a vacant lot in NYCHA’s Bushwick II campus, are currently in the RFP process and have stipulations for minimum residential senior units. Community members and elected officials called upon the administration to deliver on its promised targets by utilizing additional vacant NYCHA lots throughout the City. However, they stressed that these lots should be dedicated to the construction of deeply affordable and senior targeted units. In light of our City’s rapidly aging population, it is more crucial than ever that we invest in affordable senior housing. -

New York City Council Districts and Asian Communities (2018)

New York City Council Districts and Asian Communities (2018) 25, which includes Jackson Heights, Queens; District 38 encompassing Sunset Park, Brooklyn; and As our City Council starts this new term with 11 Introduction District 24, which include parts of Jamaica, Queens. new members and 40 returning members, the Asian American Federation has compiled data from Almost three in four Asian New Yorkers are the 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) on the immigrants. Overall, 26 percent of all immigrants Asian populations for each of the City Council citywide are Asians. Council District 20 has the Districts.1 We will highlight the growth in each highest percent of Asian immigrants among all district’s Asian population and highlight the Asian immigrant populations, accounting for 79 percent languages most commonly spoken in each district. of all immigrants in the district. District 1 has the second largest Asian immigrant population, with 66 percent of all immigrants, followed by District 23 at 60 percent; District 19 at 54 percent; District 38 at The Asian population continues to be the fastest Overall Asian Population 51 percent; and District 43 at 48 percent. growing major race and ethnic group in New York City. According to the most recent Census Bureau As Asian immigrants and their families become population estimates, the Asian population in New more established, they have become a growing part York City reached 1.23 million in 2015, accounting of the potential voter base, comprising 11 percent for nearly 15 percent of the city’s population. of the total voting-age citizen population in New York City. -

Voter Analysis Report Campaign Finance Board April 2020

20192020 VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT CAMPAIGN FINANCE BOARD APRIL 2020 NEW YORK CITY CAMPAIGN FINANCE BOARD Board Chair Frederick P. Schaffer Board Members Gregory T. Camp Richard J. Davis Marianne Spraggins Naomi B. Zauderer Amy M. Loprest Executive Director Kitty Chan Chief of Staff Sauda Chapman Assistant Executive Director for Campaign Finance Administration Daniel Cho Assistant Executive Director for Candidate Guidance and Policy Eric Friedman Assistant Executive Director for Public Affairs Hillary Weisman General Counsel THE VOTER ASSISTANCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE VAAC Chair Naomi B. Zauderer Members Daniele Gerard Joan P. Gibbs Christopher Malone Okwudiri Onyedum Mazeda Akter Uddin Jumaane Williams New York City Public Advocate (Ex-Officio) Michael Ryan Executive Director, New York City Board of Elections (Ex-Officio) The VAAC advises the CFB on voter engagement and recommends legislative and administrative changes to improve NYC elections. 2019–2020 NYC VOTES TEAM Public Affairs Partnerships and Outreach Eric Friedman Sabrina Castillo Assistant Executive Director Director for Public Affairs Matthew George-Pitt Amanda Melillo Engagement Coordinator Deputy Director for Public Affairs Sean O'Leary Field Coordinator Marketing and Digital Olivia Brady Communications Youth Coordinator Intern Charlotte Levitt Director Maya Vesneske Youth Coordinator Intern Winnie Ng Art Director Policy and Research Jen Sepso Allie Swatek Graphic Designer Director Crystal Choy Jaime Anno Production Manager Data Manager Chase Gilbert Jordan Pantalone Web Content Manager Intergovernmental Liaison Public Relations NYC Votes Street Team Matt Sollars Olivia Brady Director Adriana Espinal William Fowler Emily O'Hara Public Relations Aide Kevin Suarez Maya Vesneske VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS How COVID-19 is Affecting 2020 Elections VIII Introduction XIV I. -

Response to the Preliminary Budget

The New York City Council’s Response to the Fiscal 2022 Preliminary Budget and Fiscal 2021 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report As required under Sections 247(b) and 12(e) of the New York City Charter Hon. Corey Johnson Speaker Hon. Daniel Dromm Chair, Finance Committee Hon. Helen Rosenthal Chair, Subcommittee on Capital Budget Latonia R. McKinney Director, Finance Division April 7, 2021 Finance Division Legal Unit Revenue and Economics Unit Rebecca Chasan, Senior Counsel Raymond Majewski, Deputy Director, Chief Noah Brick Economist Stephanie Ruiz Emre Edev, Assistant Director Paul Sturm, Supervising Economist Budget Unit Hector German Regina Ryan, Deputy Director William Kyeremateng Nathan Toth, Deputy Director Nashia Roman Crilhien Francisco, Unit Head Andrew Wilber Chima Obichere, Unit Head John Russell, Unit Head Discretionary Funding and Data Support Dohini Sompura, Unit Head Unit Eisha Wright, Unit Head Paul Scimone, Deputy Director Aliya Ali James Reyes Sebastian Bacchi Savanna Chou John Basile Chelsea Baytemur Administrative Support Unit Monika Bujak Nicole Anderson Sarah Gastelum Maria Pagan Julia Haramis Courtneigh Summerrise Lauren Hunt Florentine Kabore Jack Kern Daniel Kroop Monica Pepple Michele Peregrin Masis Sarkissian Frank Sarno Jonathan Seltzer Nevin Singh Jack Storey Luke Zangerle RESPONSE TO THE FISCAL YEAR 2022 PRELIMINARY BUDGET AND FISCAL YEAR 2021 PRELIMINARY MANAGEMENT REPORT Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. -

Download and Read The

City Begins Work On New HERE TO HELP Roosevelt Island Library 10/18/2018 SENIORS: Medicare savings, Meals-on-Wheels, Access-A-Ride... HOUSING: affordable units, rent freezes, legal clinic... JOBS: search & training, veterans, senior & youth employment... FAMILIES: Universal Pre-K, Head Start, After-Schools... FINANCES: cash assistance, tax credits, home energy assistance... NUTRITION: Food Stamps (SNAP), WIC, free meals for all ages... We can also help resolve 311 Complaints. FREE LEGAL CLINICS By appointment 2:00pm to 6:00pm: • Housing, Mondays and Wednesdays • Family Law, 1st Tuesday • General Civil Law, 2nd and 4th Friday We broke ground on a new library for Roosevelt Island and cut the • Life Planning, 3rd Wednesday ribbon on a $2.5 million renovation for the 114-year-old East 67th Street Call 212-860-1950 for your appointment. Library—where I got my first library card—with funding I secured. NEW YORK CITY COUNCIL MEMBER Presorted Standard U.S. Postage PAID New York City Council 10007 BENTH KALLOS 5 DISTRICT, MANHATTAN: FALL/WINTER 2021 NEWSLETTER DISTRICT OFFICE 244 East 93rd Street New York, NY 10128 (212) 860-1950 [email protected] SAVE PAPER AND SUBSCRIBE FOR UPDATES ONCE A MONTH AT BENKALLOS.COM/SUBSCRIBE EVENTS CHANGE OF PARTY DEADLINE: State of the District Sunday, February 14, 2021 Sunday, February 21, 12:30pm VOTER REGISTRATION DEADLINE: Chess Challenge Friday, May 28, 2021 Saturday, March 13, 10:00am EARLY VOTING: June 12 - June 20, 2021 Participatory Budgeting Monday, April 5 - Wednesday, April 14 PRIMARY: Tuesday, June 22, 2021 Visit BenKallos.com/PB VOTE BY MAIL: NYCabsentee.com Upcoming Events • Shred-A-Thons • Earth Day MEET BEN • Tenants’ Rights / IN THIS ISSUE Rent Freeze Forum FIRST FRIDAY, • Overdevelopment Forum 8:00am – 10:00am, Zoom. -

2020 NYC COUNCIL ENVIRONMENTAL Scorecard Even in the Midst of a Public Health Pandemic, the New York City Council Contents Made Progress on the Environment

NEW YORK LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS 2020 NYC COUNCIL ENVIRONMENTAL Scorecard Even in the midst of a public health pandemic, the New York City Council Contents made progress on the environment. FOREWORD 3 The Council prioritized several of the policies that we highlighted in our recent NYC Policy ABOUT THE BILLS 4 Agenda that take significant steps towards our fight against climate change. A NOTE TO OUR MEMBERS 9 Our primary tool for holding Council Members accountable for supporting the priorities KEY RESULTS 10 included in the agenda is our annual New York City Council Environmental Scorecard. AVERAGE SCORES 11 In consultation with our partners from environmental, environmental justice, public LEADERSHIP 12 health, and transportation groups, we identify priority bills that have passed and those we believe have a chance of becoming law for METHODOLOGY 13 inclusion in our scorecard. We then score each Council Member based on their support of COUNCIL SCORES 14 these bills. We are pleased to report the average score for Council Members increased this year and less than a dozen Council Members received low scores, a reflection on the impact of our scorecard and the responsiveness of our elected officials. As this year’s scorecard shows, Council Members COVER IMAGE: ”BRONX-WHITESTONE BRIDGE“ are working to improve mobility, reduce waste, BY MTA / PATRICK CASHIN / CC BY 2.0 and slash emissions from buildings. 2 Even in the midst of a public health pandemic, the New York City Council made progress on the environment. They passed legislation to implement an The most recent City budget included massive e-scooter pilot program which will expand access reductions in investments in greenspaces. -

Table of Contents Table

TABLE OF CONTENTS About Citizens Union ............................................................................................................... 2 Mission ............................................................................................................................... 2 2017 Year in Review ....................................................................................................... 2 About the Voters Directory ..................................................................................................... 4 Purpose .............................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... 4 Primary Election Snapshot ...................................................................................................... 5 City Wide Elections ......................................................................................................... 6 Boroughwide Offices ....................................................................................................... 6 Civil Court Judges ............................................................................................................ 6 New York City Council ..................................................................................................... 7 Index of Uncontested Incumbents ..............................................................................10 -

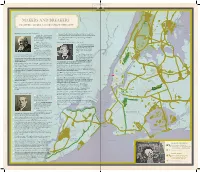

Makers and Breakers

Confidential property of University of California Press Uncorrected proofs Not for reproduction or distribution Van 12 Cortlandt Park 10 MAKERS AND BREAKERS Van Co-op Cortlandt City OLMSTED, MOSES, JACOBS SHAPE THE CITY Pelham Bay Village Park Long Island Sound frederick law olmsted (1822–1903) 14 1963–65: Presides over transformation of Flushing Meadows for BRONX o Cr ss Br onx 1 August 1840: Arrives in New its second world’s fair, which flounders in finances and attendance 11 Ex py York at 18, from Connecticut, to 15 1968: Still swims in Atlantic at age 79 near longtime Babylon, clerk for a silk importer; lodges in Long Island, home Brooklyn Heights 2 1848–55: On 125 acres jane jacobs (born Jane Butzner, 1916–2006) purchased for him by his father, 1 1934: Arrives from Scranton, builds Tosomock Farm into a PA, at age 18, intent on breaking successful nursery between stints into journalism, and with her traveling sister soon moves to the West 3 February 16, 1853: Publishes Village, their “ideal neighbor- first dispatch from the South in hood” Hudson River nascent New York Times, starting 6 5 2 7 1943: Having dropped out a series that transforms him into a staunch abolitionist, respected of Columbia’s University Exten- Riverside 4 journalist, and influential public voice Triborough Park sion, rejecting formal education, Bridge 4 Fall 1857–April 1858: Spending nights at architect Calvert Vaux’s, takes job as writer at the US collaborates -

Council District 5 About FY19 NYC Districts

COUNCIL DISTRICT 5 2019 PRIMARY CARE PROFILES A look at adult primary care access in New York City COUNCIL DISTRICT 5 Includes the Upper East Side's Yorkville, Lenox Hill, Carnegie Hill, Roosevelt Island, Midtown East, Sutton Place, and El Barrio in East Harlem neighborhoods. For comparison purposes, each metric is displayed CD MAN NYC at the city (NYC), borough (MAN), and Council District (CD) level PRIMARY CARE ACCESS Primary care access is when a person is able to 90.1% receive the primary care services needed that are 84.6 timely, affordable, and in a geographically proximate location. 94.0% 10.1% 19.4% 14.3% Primary Care Providers (PCPs) per 10,000 people 00 1010 2020 3030 4040 5050 6060 7070 1st 24.7 PCPs per 10,000 (CD) Health Insurance PCMH-Recognition 17.9 (CD) 21.2 PCPs per 10,000 (MAN) 94.0% of District 10.1% of the District's residents have health Primary Care Access Points insurance coverage are Patient-Centered Medical 9.2 PCPs per 10,000 (NYC) Home (PCMH)-Recognized 25th 74.9% 73.0% 81.0% 78.1% City Council District Ranking 13.4 (MAN) 82.8% 47.7% 6.8 (NYC) 50th Primary Care Provider Availability Medicaid Acceptance Medicare Acceptance Number of PCPs per 10,000 people. This District 82.8% of PCPs in the District 47.7% of PCPs in the District has an estimated 24.7 PCPs per 10,000 residents. accept patients with Medicaid accept patients with Medicare HEALTH STATUS Health status indicates factors that impact a population’s overall health, and the level of primary care services needed to address the health needs of a population.