Focus on New York City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Power Breakfasts

2017 Annual Report Power Breakfasts 2017’s Power Breakfast season included a diverse array of leaders from New York City and State, resulting in substantive and timely policy discussions. We welcomed the Governor, the Mayor, the Attorney General, and thought leaders on education, economics and transportation infrastructure. JANUARY 4, 2017 On January 4th, Governor Cuomo invited a panel including Department of Transportation Commissioner, Matthew Driscoll, President of the Metropolitan Transit Authority, Tom Prendergast, and Chairman of the Airport Master Plan Advisory Panel, Daniel Tishman, to present a plan to revamp the terminal, highways, and public transit leading to John F. Kennedy Airport. JANUARY 26, 2017 University Presidents Panel On January 26th leaders of some of New York City’s Universities convened to talk about the role of applied sciences in the future of higher education and how it will be used to cultivate the future work force. The panel was moderated by 1776’s Rachel Haot and included Lee C. Bollinger, President, Columbia University; Andrew Hamilton, President, New York University; Dan Huttenlocher, Dean and Vice Provost, Cornell Tech; Peretz Lavie, President, Technion - Israel Institute of Technology; and James B. Milliken, Chancellor, CUNY. MARCH 15, 2017 Budget Analysis Panel On March 15th, ABNY invited a panel of budget experts to discuss the potential impact of proposed federal policies on the New York City budget and overall economy. The panel was moderated by Maria Doulis, Vice President, Citizens Budget Commission; and the panelists included Dean Fuleihan, Director, Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget; Latonia McKinney, Director, NYC Council Finance Division; Preston Niblack, Deputy Comptroller, Office of City Comptroller; and Kenneth E. -

2018-2019 Voter Analysis Report

20182019 VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT APRIL 2019 NEW YORK CITY CAMPAIGN FINANCE BOARD Board Chair Frederick P. Schaffer Board Members Gregory T. Camp Richard J. Davis Marianne Spraggins Naomi B. Zauderer Amy M. Loprest Executive Director Roberta Maria Baldini Assistant Executive Director for Campaign Finance Administration Kitty Chan Chief of Staff Daniel Cho Assistant Executive Director for Candidate Guidance and Policy Eric Friedman Assistant Executive Director for Public Affairs Hillary Weisman General Counsel THE VOTER ASSISTANCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE VAAC Chair Naomi B. Zauderer Members Daniele Gerard Joan P. Gibbs Okwudiri Onyedum Arnaldo Segarra Mazeda Akter Uddin Jumaane Williams New York City Public Advocate (Ex-Officio) Michael Ryan Executive Director, New York City Board of Elections (Ex-Officio) The VAAC advises the CFB on voter engagement and recommends legislative and administrative changes to improve NYC elections. 2018–2019 VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT TEAM Lead Editor Gina Chung, Production Editor Lead Writer and Data Analyst Katherine Garrity, Policy and Data Research Analyst Design and Layout Winnie Ng, Art Director Jennifer Sepso, Designer Maps Jaime Anno, Data Manager WELCOME FROM THE VOTER ASSISTANCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE In this report, we take a look back at the past year and the accomplishments and challenges we experienced in our efforts to engage New Yorkers in their elections. Most excitingly, voter turnout and registration rates among New Yorkers rose significantly in 2018 for the first time since 2002, with voters turning out in record- breaking numbers for one of the most dramatic midterm elections in recent memory. Below is a list of our top findings, which we discuss in detail in this report: 1. -

Waterfront and Resilience Platform for the Next Mayor of New York City

The Waterfront and Resilience Platform for the Next Mayor of New York City We are calling on the next Mayor of New York City to ensure New York’s 520 miles of waterfront are a major priority for the In the midst of the Great administration. We will seek commitments from the candidates Depression, the federal government launched a series of outlined in the following four-point plan: building projects on a scale never seen before, touching virtually The harbor is central to the economy and regional recovery every city and town across the country. Similarly, Covid-19 recovery and major infrastructure The climate is changing and so should our waterfronts projects will be inextricably linked. Investments in the region’s clean Public access is key to breaking down physical and social energy sector and resilience barriers at the water’s edge infrastructure will be an economic boost to the region by creating well-paying, lasting, and impactful The port and maritime sector is a 21st century economic driver jobs, as we begin to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic. Further, there is an incredible opportunity to develop and deploy a BlueTech I. The Harbor is Central to the Economy and strategy which would leverage the power of the water that surrounds Regional Recovery us. This ecosystem would foster A green/blue infrastructure and jobs strategy is core to the economic startups that develop tools, recovery, as well as a broader set of protection strategies. technologies, and services needed to deepen our use of the harbor and solve complex climate and Green and Gray Infrastructure Projects maritime problems. -

Feb 11, 2018 Inauguration of NYS Senator Brian Patrick Kavanagh Hon Gale a Brewer, Manhattan Borough President Good Afternoon

Feb 11, 2018 Inauguration of NYS Senator Brian Patrick Kavanagh Hon Gale A Brewer, Manhattan Borough President Good afternoon. I’m Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, and it’s my honor and pleasure to say a few things about my colleague, confidante, and very close friend, Senator Brian Kavanagh. We go back 18 years now. It was 2001, and I’d gotten started late on my first City Council campaign. There were already six candidates in the race. We had no money. A lot of people had already taken sides, and it seemed like a long shot. Jessica Mates– another close friend and my chief of staff today – and Brian Kavanagh were there with me every day, building the campaign, stuffing 20 story buildings in the summer heat, handing out lit, keeping calm, and out–working out– thinking, and out-strategizing everybody. That, you may remember, was a Mayoral year when another candidate was running, too, a long shot we’d never heard of, a guy named Mike Bloomberg. Well, we both won, and Brian became my first chief of staff. I’d promised to “hit the ground running,” and we did thanks to Brian’s smarts and hard work, gift for organizing a staff, setting clear priorities, and managing everything in that calm, confident, steady way that is his trademark. 1 He even headed up the Fresh Democracy Project, which was a grouping of the large class of incoming Council Members in January 2002. We produced policy ideas for the new Council, but the “we” was really Brian. And he surprised us, too, with special gifts. -

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017

New York City Council Environmental SCORECARD 2017 NEW YORK LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS nylcv.org/nycscorecard INTRODUCTION Each year, the New York League of Conservation Voters improve energy efficiency, and to better prepare the lays out a policy agenda for New York City, with goals city for severe weather. we expect the Mayor and NYC Council to accomplish over the course of the proceeding year. Our primary Last month, Corey Johnson was selected by his tool for holding council members accountable for colleagues as her successor. Over the years he has progress on these goals year after year is our annual been an effective advocate in the fight against climate New York City Council Environmental Scorecard. change and in protecting the health of our most vulnerable. In particular, we appreciate his efforts In consultation with over forty respected as the lead sponsor on legislation to require the environmental, public health, transportation, parks, Department of Mental Health and Hygiene to conduct and environmental justice organizations, we released an annual community air quality survey, an important a list of eleven bills that would be scored in early tool in identifying the sources of air pollution -- such December. A handful of our selections reward council as building emissions or truck traffic -- particularly members for positive votes on the most significant in environmental justice communities. Based on this environmental legislation of the previous year. record and after he earned a perfect 100 on our City The remainder of the scored bills require council Council Scorecard in each year of his first term, NYLCV members to take a public position on a number of our was proud to endorse him for re-election last year. -

Blsa Panel Program

volunteers to combat what she felt was the community based organizations, labor unions, parents ! unnecessary destruction of young promising lives. The and educators she was responsible for developing Program is in its thirteenth year and schools are public policies to meet the needs of community involved on a word-of-mouth basis and through media residents, and create jobs for our families. coverage. The Program has grown exponentially since Ms. Gibson assisted in formulating key public its humble beginnings and now hosts 23 schools from policies that have a direct impact upon working people, Bronx, New York, Queens, and Westchester Counties. low income families, senior citizens and young people in the West Bronx including legislation to protect the Additionally, on August 10, 2007, the Generaon Next: American Bar Association recognized the Program at housing rights of Section 8 recipients, improve the their annual meeting in San Francisco. On November 4, educational opportunities for our young people, assist 2008, the residents of Bronx County elected Ms. Taylor our seniors and encourage job creation. Black in America: A Panel Discussion as Judge of the Civil Court of the City of New York. It is In November 2003 Ms. Gibson was promoted to clear that Judge Taylor’s career has been marked by Bronx District Office Manager for Assemblywoman Through much hard work, our fore-fathers and fore- her dedication and commitment to serving her Aurelia Greene and became the eyes and ears of the th mothers have painstakingly cleared the forests for community. 77 Assembly District. She managed the district office staff, worked on important West Bronx projects and us. -

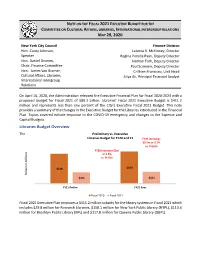

Libraries Budget Overview MAY 29,2020

NOTE ON THE FISCAL 2021 EXECUTIVE BUDGET FOR THE COMMITTEE ON CULTURAL AFFAIRS, LIBRARIES, INTERNATIONAL INTERGROUP RELATIONS MAY 29, 2020 New York City Council Finance Division Hon. Corey Johnson, Latonia R. McKinney, Director Speaker Regina Poreda Ryan, Deputy Director Hon. Daniel Dromm, Nathan Toth, Deputy Director Chair, Finance Committee Paul Scimone, Deputy Director Hon. James Van Bramer, Crilhien Francisco, Unit Head Cultural Affairs, Libraries, Aliya Ali, Principal Financial Analyst International Intergroup Relations On April 16, 2020, the Administration released the Executive Financial Plan for Fiscal 2020-2024 with a proposed budget for Fiscal 2021 of $89.3 billion. Libraries’ Fiscal 2021 Executive Budget is $411.2 million and represents less than one percent of the City’s Executive Fiscal 2021 Budget. This note provides a summary of the changes in the Executive Budget for the Libraries introduced in the Financial Plan. Topics covered include response to the COVID-19 emergency and changes to the Expense and Capital Budgets. Libraries Budget Overview The Preliminary vs. Executive Libraries Budget for FY20 and 21 FY21 increases $0.5m or 0.1% vs. Prelim FY20 increases $2m or 0.5% vs. Prelim $428 $430 Dollars in Millions $411 $411 FY21 Prelim FY21 Exec Fiscal 2020 Fiscal 2021 Fiscal 2021 Executive Plan proposes a $411.2 million subsidy for the library systems in Fiscal 2021 which includes $29.8 million for Research Libraries, $150.1 million for New York Public Library (NYPL), $113.4 million for Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) and $117.8 million for Queens Public Library (QBPL). $410.7 Million Executive Plan $411.2 Million Fiscal 2021 Changes Fiscal 2021 Executive Preliminary • Research Libraries: • New Needs: None • Research Libraries: $30.1M • Other Adjustments: $29.9M • NYPL: $149.6M 458,000 • NYPL: $150.1M • BPL: $113.2M • PEGs: None • BPL: $113.4M • QBPL: $117.8M • QBPL: $117.8M Changes introduced in the Executive Plan increase the Libraries budget for Fiscal 2021 by $500,000. -

Augural Global Ambassador with the Organization

Temple Israel of Great Neck Where tradition meets change Voice a Conservative egalitarian synagogue High Holy Days Services Temple Israel’s Yom Kippur Sunday, September 9 - Erev Rosh Hashanah Minhah and Ma’ariv 6:30 P.M. Jacob Stein Symposium Monday, September 10 - First Day Rosh Hashanah Speaker: Ruth Messinger Shaharit begins in the Sanctuary 8:15 A.M. Torah Reading: Genesis 21:1-34; Numbers 29:1-6 by Marc Katz, Editor Haftarah: I Samuel 1:1-2:10 Ruth Messinger, the former president and CEO of the American “The Days of Awe and the Workaday World: 10:00 A.M. Jewish World Service, will be the featured speaker at Temple Prayers That Connect Them” - Poetry Israel’s Jack Stein Memorial Symposium on Yom Kippur. A discussion led by Rabbi Marim D. Charry Tashlikh (Xeriscape) 6:30 P.M. American Jewish World Service is a non-profit international Minhah and Ma’ariv 7:00 P.M. development and human rights organization that supports community-based groups in 19 countries. It also works to Tuesday, September 11 - Second Day of Rosh Hashanah educate the American Jewish community about global justice. Shaharit begins in the Sanctuary 8:15 A.M. It is the only Jewish organization Torah Reading: Genesis 22:1-24; Numbers 29:1-6 dedicated solely to ending Haftarah: Jeremiah 31:1-19 poverty and promoting human “The Days of Awe and the Workaday World: 10:00 A.M. rights in the developing world. Prayers That Connect Them” - Prose A discussion led by Rabbi Marim D. Charry Rabbi Howard Stecker has been Minhah and Ma’ariv 7:10 P.M. -

The Council of the City of New York Office of Council Member Antonio

The Council of the City of New York Office of Council Member Antonio Reynoso 250 Broadway, Suite 1740 NY, New York 10007 May 10th, 2018 Press Release For Immediate Release Kristina Naplatarski [email protected] (347) 581-2050 (C) (212) 788-7095 (O) Council Member Reynoso, East Brooklyn Congregations, and Metro IAF Call Upon the de Blasio Administration to Build More Affordable Senior Housing on Unutilized NYCHA Land May 10th, 2018 —Bushwick, NY— Today, New York City Council Member Antonio Reynoso in conjunction with East Brooklyn Congregations and Metro IAF called upon the de Blasio administration to build more affordable senior housing on vacant NYCHA land. In Mayor Bill de Blasio’s 2014 “Housing New York” plan, the administration promised to increase the supply of housing for seniors by reaching 15,000 households through a combined effort of new construction and preservation. In 2017, the administration doubled this effort, aiming to serve 30,000 units over an extended 12 year period. The administration has made progress towards this goal; several sites throughout the city, including a vacant lot in NYCHA’s Bushwick II campus, are currently in the RFP process and have stipulations for minimum residential senior units. Community members and elected officials called upon the administration to deliver on its promised targets by utilizing additional vacant NYCHA lots throughout the City. However, they stressed that these lots should be dedicated to the construction of deeply affordable and senior targeted units. In light of our City’s rapidly aging population, it is more crucial than ever that we invest in affordable senior housing. -

Community Board No. 2, M Anhattan

Tobi Bergman, Chair Antony Wong, Treasurer Terri Cude, First Vice Chair Keen Berger, Secretary Susan Kent, Second Vice Chair Daniel Miller, Assistant Secretary Bob Gormley, District Manager ! COMMUNITY BOARD NO. 2, MANHATTAN 3 W ASHINGTON SQUARE V ILLAGE N EW YORK, NY 10012-1899 www.cb2manhattan.org P: 212-979-2272 F: 212-254-5102 E : [email protected] Greenwich Village v Little Italy v SoHo v NoHo v Hudson Square v Chinatown v Gansevoort Market September 28, 2016 Margaret Forgione Manhattan Borough Commissioner NYC Department of Transportation 59 Maiden Lane, 35th Floor New York, NY 10038 Dear Commissioner Forgione: At its Full Board meeting September 22, 2016, Community Board #2, adopted the following resolution: Resolution requesting a traffic study to include granite bike paths on renovated cobblestone streets. Whereas cobblestone (or Belgian Block) streets are difficult and often unsafe for cyclists to navigate in a city that is promoting bicycle use; and Whereas the uneven cobblestone streets often have large gaps with separating stones and depressions caused by use, maintenance, and weather elements that add to the peril of riding as well as walking on the stones, especially if using high heel shoes; and Whereas cobblestone streets become even more perilous when wet; and Whereas cyclists often ride on sidewalks which is dangerous and illegal to avoid the bumpy and uneven cobblestone surfaces which contributes an additional layer of safety concerns not only for cyclists but pedestrians as well; and Whereas cobblestone streets contribute to the unique, historical character that defines many Community Board 2, Manhattan (CB2) neighborhoods and need to be preserved; and Whereas other historic neighborhoods such as DUMBO have employed granite bike paths to make cycling safe in cobblestone areas without impeding on the historical character of the cobblestone street; and Whereas a successful six ft. -

Ending AIDS 2020: Blueprint to ACTION New York Academy of Sciences 250 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10007 40Th Floor July 8, 2015 – 9:00Am to 5:00Pm

Ending AIDS 2020: Blueprint to ACTION New York Academy of Sciences 250 Greenwich St, New York, NY 10007 40th Floor July 8, 2015 – 9:00am to 5:00pm 9:00am – 10:00am Registration and continental breakfast 10:00am – 11:00am Welcome and keynote remarks Moderator: Johanne Morne, NYSDOH AIDS Institute C. Virginia Fields, National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS Keynote: Alphonso David, Governor’s Office Keynote: Steven Banks, NYC Human Resources Administration 11:00am – 12:15pm Ending the Epidemic: Goals, metrics and benchmarks The Ending the Epidemic (ETE) Blueprint calls for development of key performance indicators and milestones to track the epidemic, to measure the impact of ETE activities and to continuously identify gaps in order to refine our HIV response. Panelists will discuss the current status of the epidemic in New York City and State and proposed strategies for all stakeholders to monitor progress. Moderator: Mark Harrington, Treatment Action Group HIV Epidemiology in New York State and New York City Dr. Lou Smith, NYSDOH AIDS Institute Dr. Sarah Braunstein, NYCDOHMH Proposed NYS Ending the Epidemic Benchmarks Dan O’Connell, NYSDOH AIDS Institute A Dashboard System for Tracking and Disseminating Information on Progress Towards Ending the AIDS Epidemic in New York Dr. Denis Nash, City University of New York, School of Public Health, Hunter College Campus 12:15pm – 1:00pm LUNCH 1:00pm – 2:00pm MSM and Transgender people of color – What works for populations at risk? In order to change the trajectory of the epidemic, an effective plan of action must continuously identify and address the needs of key populations that are most disadvantaged by the systemic health, economic and racial inequities that result in poor health outcomes. -

Crisis in the Court Pens a Report of the Visiting Committee of The

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. • • '. :. Crisis in the Court Pens A Report of the Visiting Committee i 1~ of the Correctional Association of New York 146095 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice j This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the '. person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positIon or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by Correctional Association of New York state to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS), Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. (DJUNE 1993 • • • • Founded in 1844, nearly 150 years ago, the Correctional Association of New York is a non • profit policy analysis and advocacy organization that focuses on criminal justice and prison issues. It is the only private entity in New York State with legislative authority to visit prisons and report its findings to policymakers and the public. The Visiting Committee of the Correctional Association's Board of Directors has the particular responsibility for carrying out this special legislative mandate. In the past several years, the • Committee has focused on conditions in New York City's court holding pens, New York State's Shock Incarceration Program, and the implementation of the regionalized Hub Program within the State's prison system. • • • • • • TABLE OF CONTENTS • ACKNOWLEDGMENTS i INTRODUCTION . .. 1 CONDITIONS IN THE PENS .................................. 2 • Crowding and other Indignities .