The New York City Campaign Finance Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-2019 Voter Analysis Report

20182019 VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT APRIL 2019 NEW YORK CITY CAMPAIGN FINANCE BOARD Board Chair Frederick P. Schaffer Board Members Gregory T. Camp Richard J. Davis Marianne Spraggins Naomi B. Zauderer Amy M. Loprest Executive Director Roberta Maria Baldini Assistant Executive Director for Campaign Finance Administration Kitty Chan Chief of Staff Daniel Cho Assistant Executive Director for Candidate Guidance and Policy Eric Friedman Assistant Executive Director for Public Affairs Hillary Weisman General Counsel THE VOTER ASSISTANCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE VAAC Chair Naomi B. Zauderer Members Daniele Gerard Joan P. Gibbs Okwudiri Onyedum Arnaldo Segarra Mazeda Akter Uddin Jumaane Williams New York City Public Advocate (Ex-Officio) Michael Ryan Executive Director, New York City Board of Elections (Ex-Officio) The VAAC advises the CFB on voter engagement and recommends legislative and administrative changes to improve NYC elections. 2018–2019 VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT TEAM Lead Editor Gina Chung, Production Editor Lead Writer and Data Analyst Katherine Garrity, Policy and Data Research Analyst Design and Layout Winnie Ng, Art Director Jennifer Sepso, Designer Maps Jaime Anno, Data Manager WELCOME FROM THE VOTER ASSISTANCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE In this report, we take a look back at the past year and the accomplishments and challenges we experienced in our efforts to engage New Yorkers in their elections. Most excitingly, voter turnout and registration rates among New Yorkers rose significantly in 2018 for the first time since 2002, with voters turning out in record- breaking numbers for one of the most dramatic midterm elections in recent memory. Below is a list of our top findings, which we discuss in detail in this report: 1. -

Club Proposal Rappea

sneaonaacricaEe^s o County JLeadet Newspapers o U) VOL.58NO.02 I " " SPRINGFIELD, M\J.,THURSDAY,OCTOBER 23,1984-2* '"i Two sections in * 1 .si" in Club proposal rappea By-MARK YABLONSKY outrageous. I don't know 'what Bill shouldn't be considered. I am in A recent proposal from the Boys Cieri couldJiave been thinking of shock." . and Girls Club of Union that would when he proposed this idea. Now, it's Cieri, who originally introduced bring a "satellite'^ branch of. the the idea to Triolo several months national organization to Springfield ago, soys the club's offering was not has drawn sharp criticism from necessarilyiinal. " ••I leading—township recreation-of- LWV plans I4!ij jvll] ^l^^v^^o^^^^m "That doesn't mean we're going to - ficials, who have berated the plan as . ''outrageous." ; . : ,' • two forums accept their proposal,"-Says Cieri, Township Commltteewoman Jo- adding "that (he governing body . Ann Pieper and Recreation Director ' The Springfield League of would meet with the Boys and Girls Mark Silance have charged that the Women .Voters will hold its an- Club qdmmiltee in order to deter- proposal submitted to Mayor nual candidates' night on Oct.'27 mine what services the organization William Cieri by the Union club - at 8 p.m. in- the 'cafeteria of would provide. which is one of niore than 1,100 Gaudineer School. The public is nationwide — will cost the town too invited to hear the candidates' , "Their terms are not necessarily - much hioney and will usurp the platforms and to ask questions of- the final terms!-As far as I'm con- authority and need of the township's The candidates. -

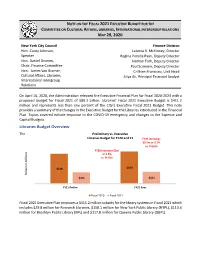

Libraries Budget Overview MAY 29,2020

NOTE ON THE FISCAL 2021 EXECUTIVE BUDGET FOR THE COMMITTEE ON CULTURAL AFFAIRS, LIBRARIES, INTERNATIONAL INTERGROUP RELATIONS MAY 29, 2020 New York City Council Finance Division Hon. Corey Johnson, Latonia R. McKinney, Director Speaker Regina Poreda Ryan, Deputy Director Hon. Daniel Dromm, Nathan Toth, Deputy Director Chair, Finance Committee Paul Scimone, Deputy Director Hon. James Van Bramer, Crilhien Francisco, Unit Head Cultural Affairs, Libraries, Aliya Ali, Principal Financial Analyst International Intergroup Relations On April 16, 2020, the Administration released the Executive Financial Plan for Fiscal 2020-2024 with a proposed budget for Fiscal 2021 of $89.3 billion. Libraries’ Fiscal 2021 Executive Budget is $411.2 million and represents less than one percent of the City’s Executive Fiscal 2021 Budget. This note provides a summary of the changes in the Executive Budget for the Libraries introduced in the Financial Plan. Topics covered include response to the COVID-19 emergency and changes to the Expense and Capital Budgets. Libraries Budget Overview The Preliminary vs. Executive Libraries Budget for FY20 and 21 FY21 increases $0.5m or 0.1% vs. Prelim FY20 increases $2m or 0.5% vs. Prelim $428 $430 Dollars in Millions $411 $411 FY21 Prelim FY21 Exec Fiscal 2020 Fiscal 2021 Fiscal 2021 Executive Plan proposes a $411.2 million subsidy for the library systems in Fiscal 2021 which includes $29.8 million for Research Libraries, $150.1 million for New York Public Library (NYPL), $113.4 million for Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) and $117.8 million for Queens Public Library (QBPL). $410.7 Million Executive Plan $411.2 Million Fiscal 2021 Changes Fiscal 2021 Executive Preliminary • Research Libraries: • New Needs: None • Research Libraries: $30.1M • Other Adjustments: $29.9M • NYPL: $149.6M 458,000 • NYPL: $150.1M • BPL: $113.2M • PEGs: None • BPL: $113.4M • QBPL: $117.8M • QBPL: $117.8M Changes introduced in the Executive Plan increase the Libraries budget for Fiscal 2021 by $500,000. -

Carey Easily Beats Durye a GOP Takes Comptroller; Drops Attny

Carey Easily Beats Durye a GOP Takes Comptroller; Drops Attny. Gen. New York (AP)- by 56 percent to 44 Governor Hugh Carey percent. won a big re-election Republican Edward victory over challenger Regan, the Erie County Perry Duryea, the Montauk executive, appeared to have Assemblyman, yesterday, upset New York City defeating Republican efforts comptroller Harrison to turn the balloting into a Goldin in the race for state referendum over the death comptroller. Goldin led in penalty. New York City but trailed He hailed the large voter badly in the rest of the turnout across the state, state. and said that "this goes (See stories, page 7) against all the experts, who On the slate with Carey said there would be as the Democratic indifference, apathy and a candidate for lieutenant low vote." governor was Secretary of Duryea conceded just State Mario Cuomo; before midnight and said he Duryea's running mate on had sent a telegram to the Republican ticket was Carey, "I wish you well." United States With 42 percent of the Representative Bruce state's election districts Caputo of Yonkers. counted, it was Carey 56 Carey, a liberal by percent and Duryea 44 instinct, made fiscal 3 b ull kpv!rcAnnp nf hlr prlcnllt. otU.L)LercentD t AJLyLJ,,, oXV0uy l ·rpetr.int. county, Suffolk, opted for administration and his him by an overwhelming campaign stance. In the past 43,000 vote margin. two years he signed into law The voting produced the the first significant state tax ouster of one major figure cuts in 20 years, and he in state politics - Assembly boasted about a rate of Speaker Stanley Steingut, a growth in the state's budget Democrat, who lost in his which he said was well Brooklyn district. -

The Council of the City of New York Office of Council Member Antonio

The Council of the City of New York Office of Council Member Antonio Reynoso 250 Broadway, Suite 1740 NY, New York 10007 May 10th, 2018 Press Release For Immediate Release Kristina Naplatarski [email protected] (347) 581-2050 (C) (212) 788-7095 (O) Council Member Reynoso, East Brooklyn Congregations, and Metro IAF Call Upon the de Blasio Administration to Build More Affordable Senior Housing on Unutilized NYCHA Land May 10th, 2018 —Bushwick, NY— Today, New York City Council Member Antonio Reynoso in conjunction with East Brooklyn Congregations and Metro IAF called upon the de Blasio administration to build more affordable senior housing on vacant NYCHA land. In Mayor Bill de Blasio’s 2014 “Housing New York” plan, the administration promised to increase the supply of housing for seniors by reaching 15,000 households through a combined effort of new construction and preservation. In 2017, the administration doubled this effort, aiming to serve 30,000 units over an extended 12 year period. The administration has made progress towards this goal; several sites throughout the city, including a vacant lot in NYCHA’s Bushwick II campus, are currently in the RFP process and have stipulations for minimum residential senior units. Community members and elected officials called upon the administration to deliver on its promised targets by utilizing additional vacant NYCHA lots throughout the City. However, they stressed that these lots should be dedicated to the construction of deeply affordable and senior targeted units. In light of our City’s rapidly aging population, it is more crucial than ever that we invest in affordable senior housing. -

New York City Council Districts and Asian Communities (2018)

New York City Council Districts and Asian Communities (2018) 25, which includes Jackson Heights, Queens; District 38 encompassing Sunset Park, Brooklyn; and As our City Council starts this new term with 11 Introduction District 24, which include parts of Jamaica, Queens. new members and 40 returning members, the Asian American Federation has compiled data from Almost three in four Asian New Yorkers are the 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) on the immigrants. Overall, 26 percent of all immigrants Asian populations for each of the City Council citywide are Asians. Council District 20 has the Districts.1 We will highlight the growth in each highest percent of Asian immigrants among all district’s Asian population and highlight the Asian immigrant populations, accounting for 79 percent languages most commonly spoken in each district. of all immigrants in the district. District 1 has the second largest Asian immigrant population, with 66 percent of all immigrants, followed by District 23 at 60 percent; District 19 at 54 percent; District 38 at The Asian population continues to be the fastest Overall Asian Population 51 percent; and District 43 at 48 percent. growing major race and ethnic group in New York City. According to the most recent Census Bureau As Asian immigrants and their families become population estimates, the Asian population in New more established, they have become a growing part York City reached 1.23 million in 2015, accounting of the potential voter base, comprising 11 percent for nearly 15 percent of the city’s population. of the total voting-age citizen population in New York City. -

Voter Analysis Report Campaign Finance Board April 2020

20192020 VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT CAMPAIGN FINANCE BOARD APRIL 2020 NEW YORK CITY CAMPAIGN FINANCE BOARD Board Chair Frederick P. Schaffer Board Members Gregory T. Camp Richard J. Davis Marianne Spraggins Naomi B. Zauderer Amy M. Loprest Executive Director Kitty Chan Chief of Staff Sauda Chapman Assistant Executive Director for Campaign Finance Administration Daniel Cho Assistant Executive Director for Candidate Guidance and Policy Eric Friedman Assistant Executive Director for Public Affairs Hillary Weisman General Counsel THE VOTER ASSISTANCE ADVISORY COMMITTEE VAAC Chair Naomi B. Zauderer Members Daniele Gerard Joan P. Gibbs Christopher Malone Okwudiri Onyedum Mazeda Akter Uddin Jumaane Williams New York City Public Advocate (Ex-Officio) Michael Ryan Executive Director, New York City Board of Elections (Ex-Officio) The VAAC advises the CFB on voter engagement and recommends legislative and administrative changes to improve NYC elections. 2019–2020 NYC VOTES TEAM Public Affairs Partnerships and Outreach Eric Friedman Sabrina Castillo Assistant Executive Director Director for Public Affairs Matthew George-Pitt Amanda Melillo Engagement Coordinator Deputy Director for Public Affairs Sean O'Leary Field Coordinator Marketing and Digital Olivia Brady Communications Youth Coordinator Intern Charlotte Levitt Director Maya Vesneske Youth Coordinator Intern Winnie Ng Art Director Policy and Research Jen Sepso Allie Swatek Graphic Designer Director Crystal Choy Jaime Anno Production Manager Data Manager Chase Gilbert Jordan Pantalone Web Content Manager Intergovernmental Liaison Public Relations NYC Votes Street Team Matt Sollars Olivia Brady Director Adriana Espinal William Fowler Emily O'Hara Public Relations Aide Kevin Suarez Maya Vesneske VOTER ANALYSIS REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS How COVID-19 is Affecting 2020 Elections VIII Introduction XIV I. -

Response to the Preliminary Budget

The New York City Council’s Response to the Fiscal 2022 Preliminary Budget and Fiscal 2021 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report As required under Sections 247(b) and 12(e) of the New York City Charter Hon. Corey Johnson Speaker Hon. Daniel Dromm Chair, Finance Committee Hon. Helen Rosenthal Chair, Subcommittee on Capital Budget Latonia R. McKinney Director, Finance Division April 7, 2021 Finance Division Legal Unit Revenue and Economics Unit Rebecca Chasan, Senior Counsel Raymond Majewski, Deputy Director, Chief Noah Brick Economist Stephanie Ruiz Emre Edev, Assistant Director Paul Sturm, Supervising Economist Budget Unit Hector German Regina Ryan, Deputy Director William Kyeremateng Nathan Toth, Deputy Director Nashia Roman Crilhien Francisco, Unit Head Andrew Wilber Chima Obichere, Unit Head John Russell, Unit Head Discretionary Funding and Data Support Dohini Sompura, Unit Head Unit Eisha Wright, Unit Head Paul Scimone, Deputy Director Aliya Ali James Reyes Sebastian Bacchi Savanna Chou John Basile Chelsea Baytemur Administrative Support Unit Monika Bujak Nicole Anderson Sarah Gastelum Maria Pagan Julia Haramis Courtneigh Summerrise Lauren Hunt Florentine Kabore Jack Kern Daniel Kroop Monica Pepple Michele Peregrin Masis Sarkissian Frank Sarno Jonathan Seltzer Nevin Singh Jack Storey Luke Zangerle RESPONSE TO THE FISCAL YEAR 2022 PRELIMINARY BUDGET AND FISCAL YEAR 2021 PRELIMINARY MANAGEMENT REPORT Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. -

Download and Read The

City Begins Work On New HERE TO HELP Roosevelt Island Library 10/18/2018 SENIORS: Medicare savings, Meals-on-Wheels, Access-A-Ride... HOUSING: affordable units, rent freezes, legal clinic... JOBS: search & training, veterans, senior & youth employment... FAMILIES: Universal Pre-K, Head Start, After-Schools... FINANCES: cash assistance, tax credits, home energy assistance... NUTRITION: Food Stamps (SNAP), WIC, free meals for all ages... We can also help resolve 311 Complaints. FREE LEGAL CLINICS By appointment 2:00pm to 6:00pm: • Housing, Mondays and Wednesdays • Family Law, 1st Tuesday • General Civil Law, 2nd and 4th Friday We broke ground on a new library for Roosevelt Island and cut the • Life Planning, 3rd Wednesday ribbon on a $2.5 million renovation for the 114-year-old East 67th Street Call 212-860-1950 for your appointment. Library—where I got my first library card—with funding I secured. NEW YORK CITY COUNCIL MEMBER Presorted Standard U.S. Postage PAID New York City Council 10007 BENTH KALLOS 5 DISTRICT, MANHATTAN: FALL/WINTER 2021 NEWSLETTER DISTRICT OFFICE 244 East 93rd Street New York, NY 10128 (212) 860-1950 [email protected] SAVE PAPER AND SUBSCRIBE FOR UPDATES ONCE A MONTH AT BENKALLOS.COM/SUBSCRIBE EVENTS CHANGE OF PARTY DEADLINE: State of the District Sunday, February 14, 2021 Sunday, February 21, 12:30pm VOTER REGISTRATION DEADLINE: Chess Challenge Friday, May 28, 2021 Saturday, March 13, 10:00am EARLY VOTING: June 12 - June 20, 2021 Participatory Budgeting Monday, April 5 - Wednesday, April 14 PRIMARY: Tuesday, June 22, 2021 Visit BenKallos.com/PB VOTE BY MAIL: NYCabsentee.com Upcoming Events • Shred-A-Thons • Earth Day MEET BEN • Tenants’ Rights / IN THIS ISSUE Rent Freeze Forum FIRST FRIDAY, • Overdevelopment Forum 8:00am – 10:00am, Zoom. -

![Tony Schwartz Collection [Finding Aid]. Library Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8976/tony-schwartz-collection-finding-aid-library-of-1278976.webp)

Tony Schwartz Collection [Finding Aid]. Library Of

Tony Schwartz Collection Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2012 Revised March 2014 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsrs/mbrsrs.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsrs/eadmbrs.rs011002 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2012618550 Authors: Carla Arton, Harrison Behl, Callie Holmes, David Jackson, Maya Lerman, Marsha Maguire, Adam Thaxter, Celeste Welch Collection Summary Title: Tony Schwartz collection Inclusive Dates: 1912-2008 Bulk Dates: 1950-2008 Creator: Schwartz, Tony Textual materials: 90.5 linear feet (230 boxes, 1 map case folder, approximately 76,345 items) Language: Collection materials are in English Location: Recorded Sound Reference Center, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: The Tony Schwartz Collection consists of multiple formats of material documenting Schwartz's work as a media consultant, audio documentarian, author, radio producer, media theorist, and educator. Location: RPA 00856-01055 (boxes 1-200); RPB 00112-00122 (oversize boxes 213-223); RPC 00084-00087 (oversize boxes 224-227); RPD 00038-00040 (oversize boxes 228-230); RPU 00002 (box 201), RPU 00021-00023 (boxes 202-204), RPU 00024 (box OSU 1), RPU 00025-00032 (boxes 205-212) Map case: RPM 00013 (map folder 1) Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Bemporad, Jack. Bleviss, Alan. Bredesen, Phil, 1943- Carey, John, 1946- Carter, Jimmy, 1924- Cherner, Joe. -

2020 NYC COUNCIL ENVIRONMENTAL Scorecard Even in the Midst of a Public Health Pandemic, the New York City Council Contents Made Progress on the Environment

NEW YORK LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS 2020 NYC COUNCIL ENVIRONMENTAL Scorecard Even in the midst of a public health pandemic, the New York City Council Contents made progress on the environment. FOREWORD 3 The Council prioritized several of the policies that we highlighted in our recent NYC Policy ABOUT THE BILLS 4 Agenda that take significant steps towards our fight against climate change. A NOTE TO OUR MEMBERS 9 Our primary tool for holding Council Members accountable for supporting the priorities KEY RESULTS 10 included in the agenda is our annual New York City Council Environmental Scorecard. AVERAGE SCORES 11 In consultation with our partners from environmental, environmental justice, public LEADERSHIP 12 health, and transportation groups, we identify priority bills that have passed and those we believe have a chance of becoming law for METHODOLOGY 13 inclusion in our scorecard. We then score each Council Member based on their support of COUNCIL SCORES 14 these bills. We are pleased to report the average score for Council Members increased this year and less than a dozen Council Members received low scores, a reflection on the impact of our scorecard and the responsiveness of our elected officials. As this year’s scorecard shows, Council Members COVER IMAGE: ”BRONX-WHITESTONE BRIDGE“ are working to improve mobility, reduce waste, BY MTA / PATRICK CASHIN / CC BY 2.0 and slash emissions from buildings. 2 Even in the midst of a public health pandemic, the New York City Council made progress on the environment. They passed legislation to implement an The most recent City budget included massive e-scooter pilot program which will expand access reductions in investments in greenspaces. -

THE PATENT BATTLE THAT CREATED HOLLYWOOD by David Krell 10

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2015 VOL. 87 | NO. 9 JournalNEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Also in this Issue The Patent Battle Eight “Chiefs” That Created Criminal Justice Update Medical Malpractice Hollywood Proving a Joint Account By David Krell Simplify your everything. Your time is precious. That’s why Clio®’s intuitive design and powerful functionality will smooth out your processes and uncomplicate your overly-complex life. When your business systems are easy-to-use, intelligent and uncomplicated, you can put yourself first and prioritize your day accordingly. Simplify with Clio – the most complete and streamlined legal management solution around. We save you time. It’s up to you what you do with it. We’re the most comprehensive, yet easy-to-use cloud-based law practice management software. Join tens of thousands of legal professionals who trust Clio to manage and grow their firms. Start your free trial today at clio.com Simplify your everything. Clio® and the Clio Checkmark Logo™ are Trademarks or registered Trademarks of Themis Solutions Inc. ©2015 Themis Solutions Inc. All rights reserved. BESTSELLERS FROM THE NYSBA BOOKSTORE November/December 2015 Best Practices in Legal Management Entertainment Law, 4th Ed. NYSBA Practice Forms on CD 2014–2015 The most complete treatment of the business of Completely revised, Entertainment Law, More than 500 of the forms from Deskbook running a law firm. With forms on CD. 4th Edition covers the principal areas of enter- and Formbook used by experienced practitio- PN: 4131 / Member $139 / List $179 / tainment law. ners in their daily practice. 498 pages PN: 40862 / Member $150 / List $175 / Practice of Criminal Law Under the CPLR and 986 pages/loose-leaf Criminal and Civil Contempt, 2nd Ed.