Evaluation of the Vicroads Community Policing and Education Project: Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victoria Rural Addressing State Highways Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions

23 0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 MILDURA Direction of Rural Numbering 0 Victoria 00 00 Highway 00 00 00 Sturt 00 00 00 110 00 Hwy_name From To Distance Bass Highway South Gippsland Hwy @ Lang Lang South Gippsland Hwy @ Leongatha 93 Rural Addressing Bellarine Highway Latrobe Tce (Princes Hwy) @ Geelong Queenscliffe 29 Bonang Road Princes Hwy @ Orbost McKillops Rd @ Bonang 90 Bonang Road McKillops Rd @ Bonang New South Wales State Border 21 Borung Highway Calder Hwy @ Charlton Sunraysia Hwy @ Donald 42 99 State Highways Borung Highway Sunraysia Hwy @ Litchfield Borung Hwy @ Warracknabeal 42 ROBINVALE Calder Borung Highway Henty Hwy @ Warracknabeal Western Highway @ Dimboola 41 Calder Alternative Highway Calder Hwy @ Ravenswood Calder Hwy @ Marong 21 48 BOUNDARY BEND Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions Calder Highway Kyneton-Trentham Rd @ Kyneton McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo 65 0 Calder Highway McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn 73 000000 000000 000000 Calder Highway Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof 62 Murray MILDURA Calder Highway Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake 77 Calder Highway Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen 88 Calder Highway Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura 99 Calder Highway Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura Murray River @ Yelta 23 Glenelg Highway Midland Hwy @ Ballarat Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham 76 OUYEN Highway 0 0 97 000000 PIANGIL Glenelg Highway Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham Lonsdale -

Schedule 2.Pdf

REGIONAL STRATEGY PLAN - SCHEDULE TWO - SITES OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE SCHEDULE TWO SITES OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE PART A. SITES OR FEATURES OF HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE, AND OTHER SITES OR FEATURES OF SIGNIFICANCE. A full explanation and identification of the Sites and Features listed in Part A of this Schedule may be found in the Report by the Upper Yarra Valley and Dandenong Ranges Authority (1988) Conservation of Sites and Structures of Historical and Archaeological Significance. The Authority may from time to time, and on the basis of further research, identify additional sites and features and add those to this Schedule. The Authority will, from time to time, advise the general public, Councils, Government Departments and Public Authorities of modifications to this listing. 1. EXISTING SITES OR FEATURES OF HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE Former Shire of Healesville Brick house Cnr. Bell Street & Armstrong Grove Yarra Glen Coranderrk Aboriginal Cemetery Picaninny Lane, Healesville Court House Cnr. Heallesville-Kinglake Road & Hawker Street, Healesville ‘Cranbrooke Lodge’ (New Life for Westmount Road, Healesville All Conference Centre) ‘The Elms’ slab cottage Tarrawarra (‘Notre Dame’) Abbey, Tarrawarra (Yarra Glen-Healesville Road) Former Mechanics Institute Hall 4 Church Street, Healesville Former Coranderrk Aboriginal Picaninny Lane, Helaesville Station Superintendent’s house Grand Hotel (Yarra Glen) Melba Highway, Yarra Glen Grand Hotel (Healesville) Cnr. Maroondah Highway & Green Street Healesville ‘Gulf Station’ Melba Highway, Yarra Glen -

Height Clearance Under Structures for Permit Vehicles

SEPTEMBER 2007 Height Clearance Under Structures for Permit Vehicles INFORMATION BULLETIN Height Clearance A vehicle must not travel or attempt to travel: Under Structures for (a) beneath a bridge or overhead Permit Vehicles structure that carries a sign with the words “LOW CLEARANCE” or This information bulletin shows the “CLEARANCE” if the height of the clearance between the road surface and vehicle, including its load, is equal to overhead structures and is intended to or greater than the height shown on assist truck operators and drivers to plan the sign; or their routes. (b) beneath any other overhead It lists the roads with overhead structures structures, cables, wires or trees in alphabetical order for ready reference. unless there is at least 200 millimetres Map references are from Melway Greater clearance to the highest point of the Melbourne Street Directory Edition 34 (2007) vehicle. and Edition 6 of the RACV VicRoads Country Every effort has been made to ensure that Street Directory of Victoria. the information in this bulletin is correct at This bulletin lists the locations and height the time of publication. The height clearance clearance of structures over local roads figures listed in this bulletin, measured in and arterial roads (freeways, highways, and metres, are a result of field measurements or main roads) in metropolitan Melbourne sign posted clearances. Re-sealing of road and arterial roads outside Melbourne. While pavements or other works may reduce the some structures over local roads in rural available clearance under some structures. areas are listed, the relevant municipality Some works including structures over local should be consulted for details of overhead roads are not under the control of VicRoads structures. -

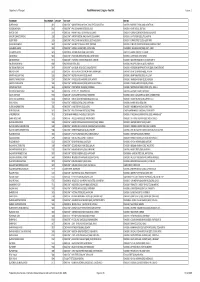

Copy of RMC List Statewide FINAL 20201207 to Be Published .Xlsx

Department of Transport Road Maintenance Category - Road List Version : 1 ROAD NAME ROAD NUMBER CATEGORY RMC START RMC END ACHERON WAY 4811 4 ROAD START - WARBURTON-WOODS POINT ROAD (5957), WARBURTON ROAD END - MARYSVILLE ROAD (4008), NARBETHONG AERODROME ROAD 5616 4 ROAD START - PRINCES HIGHWAY EAST (6510), SALE ROAD END - HEART AVENUE, EAST SALE AIRPORT ROAD 5579 4 ROAD START - MURRAY VALLEY HIGHWAY (6570), KERANG ROAD END - KERANG-KOONDROOK ROAD (5578), KERANG AIRPORT CONNECTION ROAD 1280 2 ROAD START - AIRPORT-WESTERN RING IN RAMP, TULLAMARINE ROAD END - SHARPS ROAD (5053), TULLAMARINE ALBERT ROAD 5128 2 ROAD START - PRINCES HIGHWAY EAST (6510), SOUTH MELBOURNE ROAD END - FERRARS STREET (5130), ALBERT PARK ALBION ROAD BRIDGE 5867 3 ROAD START - 50M WEST OF LAWSON STREET, ESSENDON ROAD END - 15M EAST OF HOPETOUN AVENUE, BRUNSWICK WEST ALEXANDRA AVENUE 5019 3 ROAD START - HODDLE HIGHWAY (6080), SOUTH YARRA ROAD BREAK - WILLIAMS ROAD (5998), SOUTH YARRA ALEXANDRA AVENUE 5019 3 ROAD BREAK - WILLIAMS ROAD (5998), SOUTH YARRA ROAD END - GRANGE ROAD (5021), TOORAK ANAKIE ROAD 5893 4 ROAD START - FYANSFORD-CORIO ROAD (5881), LOVELY BANKS ROAD END - ASHER ROAD, LOVELY BANKS ANDERSON ROAD 5571 3 ROAD START - FOOTSCRAY-SUNSHINE ROAD (5877), SUNSHINE ROAD END - MCINTYRE ROAD (5517), SUNSHINE NORTH ANDERSON LINK ROAD 6680 3 BASS HIGHWAY (6710), BASS ROAD END - PHILLIP ISLAND ROAD (4971), ANDERSON ANDERSONS CREEK ROAD 5947 3 ROAD START - BLACKBURN ROAD (5307), DONCASTER EAST ROAD END - HEIDELBERG-WARRANDYTE ROAD (5809), DONCASTER EAST ANGLESEA -

683 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

683 bus time schedule & line map 683 Warburton - Chirnside Park SC View In Website Mode The 683 bus line (Warburton - Chirnside Park SC) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chirnside Park Sc: 5:37 AM - 8:25 PM (2) Warburton: 6:37 AM - 9:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 683 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 683 bus arriving. Direction: Chirnside Park Sc 683 bus Time Schedule 66 stops Chirnside Park Sc Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:43 AM - 8:31 PM Monday 5:37 AM - 8:25 PM Whitegum Dr/Woods Point Rd (East Warburton) Tuesday 5:37 AM - 8:25 PM Outlook Ave/Woods Point Rd (East Warburton) 9 Elderberry Avenue, Warburton East Wednesday 5:37 AM - 8:25 PM Herbert Ave/Woods Point Rd (East Warburton) Thursday 5:37 AM - 8:25 PM 474 Woods Point Road, Warburton East Friday 5:37 AM - 8:25 PM Millwarra Ps/Woods Point Rd (East Warburton) Saturday 7:17 AM - 8:31 PM 410 Woods Point Road, Warburton East Rupert Rd/Woods Point Rd (East Warburton) Marion Park Gardens B&B/Opp 171 Woods Point 683 bus Info Rd (Warburton) Direction: Chirnside Park Sc 171 Woods Point Road, East Warburton Stops: 66 Trip Duration: 64 min Yarra View Ret Village/Warburton Hwy Line Summary: Whitegum Dr/Woods Point Rd (East (Warburton) Warburton), Outlook Ave/Woods Point Rd (East Warburton Highway, Warburton Warburton), Herbert Ave/Woods Point Rd (East Warburton), Millwarra Ps/Woods Point Rd (East Park Rd/Warburton Hwy (Warburton) Warburton), Rupert Rd/Woods Point Rd (East 3466 Warburton Highway, Warburton Warburton), -

Sixty-Sixth Annual Report

VICTORIA COUNTRY ROADS BOARD Sixty-sixth Annual Report For the year ended 30 June 1979 Presented to Both Houses of Parliament Pursuant to Act No. 6229 MELBOURNE F. D. ATKINSON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER 1979 No. 45 f 60 Denmark Street, Kew 3101 28th September, 1979 The Honorable Robert Maclellan, MLA Minister of Transport 570 Bourke Street. Melbourne 3000 Sir In accordance with the requirements of Section 128 of the Country Roads Act 1958 No. 6229, the Board submits to you for presentation to Parliament the report of its proceedings for the year ended 30th June, 1979. The Board wishes to thank the Government for the support and interest in its activities and wishes to place on record its appreciation of the continued co-operation and assistance of State Ministers, Government departments, State instrumentalities and municipal councils. The Board also pays tribute to the continued loyal co-operation and work done by its staff and employees throughout the year. Yours faithfully T H Russell MEngSc (Hons.), BCE (Hons.), DipCE, FIEAust. Chairman WSBrake BCE, CE, M lE Aust. Deputy Chairman N LAIIanson AASA (Senior}, JP Member G KCox LLB, JP Secretary I' "t Country Roads Board Victoria Sixty-sixth Annual Report for year ended 30th June, 1979 Presented to both Houses of Parliament pursuant to Act No. 6229 The CRB is the State Road Authority of Victoria. The CRB's aim is to create an efficient road system within the context • of the overall transportation needs of the community. There are about 160,000 km of public roads in Victoria, of which 23,706 km comprise the CRB's network of the State's principal roads. -

965 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

965 bus time schedule & line map 965 Healesville View In Website Mode The 965 bus line Healesville has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Healesville: 4:48 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 965 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 965 bus arriving. Direction: Healesville 965 bus Time Schedule 10 stops Healesville Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 4:48 AM Monday Not Operational Lilydale Station/Maroondah Hwy (Lilydale) 99 Main Street, Lilydale Tuesday Not Operational Nelson Rd/Maroondah Hwy (Lilydale) Wednesday Not Operational 473 Maroondah Highway, Lilydale Thursday Not Operational Union Rd/Warburton Hwy (Wandin North) Friday Not Operational 365 Warburton Highway, Wandin North Saturday 4:48 AM Link Rd/Warburton Hwy (Seville) 555 Warburton Highway, Seville Healesville-Koo Wee Rup Rd/Warburton Hwy (Woori Yallock) 965 bus Info 2/1585 Warburton Highway, Seville Direction: Healesville Stops: 10 Maroondah Hwy/Green St (Healesville) Trip Duration: 90 min 5 Green Street, Healesville Line Summary: Lilydale Station/Maroondah Hwy (Lilydale), Nelson Rd/Maroondah Hwy (Lilydale), Herbert Rd/Melba Hwy (Yarra Glen) Union Rd/Warburton Hwy (Wandin North), Link 6/36 Bell Street, Yarra Glen Rd/Warburton Hwy (Seville), Healesville-Koo Wee Rup Rd/Warburton Hwy (Woori Yallock), Maroondah North Gtwy/Maroondah Hwy (Coldstream) Hwy/Green St (Healesville), Herbert Rd/Melba Hwy Maroondah Highway, Lilydale (Yarra Glen), North Gtwy/Maroondah Hwy (Coldstream), Cyril St/Maroondah Hwy (Lilydale), Cyril St/Maroondah Hwy (Lilydale) Lilydale Station/Maroondah Hwy (Lilydale) 476 Maroondah Highway, Lilydale Lilydale Station/Maroondah Hwy (Lilydale) 99 Main Street, Lilydale 965 bus time schedules and route maps are available in an o«ine PDF at moovitapp.com. -

Additional Permit Conditions

ADDITIONAL PERMIT CONDITIONS The following conditions must be complied with in addition to any specific conditions contained elsewhere in the permit document. OD Routes referred to in the permit document are described at the end of the conditions. (a) in the case of a vehicle exceeding 2.5 metres in 1. INTRODUCTION width or 25.0 metres in length– 1.1 In these conditions, unless the contrary intention (i) four bright red, yellow or red and yellow flags; appears– (ii) a rigid OVERSIZE warning sign attached to the front and rear of the vehicle; and (a) “permit vehicle” means the vehicle or combination (b) if the vehicle exceeds 3.0 metres in width, a yellow in respect of which the permit has been issued; warning light; and (b) “operator’ means the person in whose name the (c) if the vehicle exceeds 22.0 metres in length– permit is issued and includes any principal on whose behalf that person has obtained the permit; (i) a rigid OVERSIZE warning sign attached to the rear of the vehicle; (c) “the Regulations” means the Road Safety (Vehicles) Regulations 1999; 2.7 The warning lights and warning signs must meet the (d) words and phrases have the same meaning as in construction standards and specifications set out in the Regulations. Schedule 1 to the Regulations. 1.2 Unless the contrary intention expressly appears in the permit document, this permit does not apply if the permit vehicle is being operated under any other permit or Gazette Notice issued or published under Part 5 of the Regulations. -

Latrobe Northern

o! E o! E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E o! E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E # +$# # E # # # WOODS POINT - N#ARBE#THO#NG BIG RIVER OLD COACH ROAD GLENCAIRN - # SO#UTH D#OM FRENCHMANS BARKLEY RIVER DOM RD CREEK CHUM CREEK - XANTHORRHOEA TRACK Deep Joint Fuel Creek RA CAMBARVILLE - E y Hw BEARS CREEK ah Matlock nd oo ar M MATLOCK - WALHALLA HEALESVILLE - ROAD 21 ROAD Management Walsh E Creek RA Licola Maroondah Reservoir REEFTON - Program FISHERMAN DRIVE REEFTON The Triangle Healesville HEALESVILLE - - BATTS MT RIDDLE ROAD CREEK JERICHO - FFMVIC LATROBE POOLE ROAD BADGER CREEK - REEFTON - PICANINNY CREEK +$ +$+$ TWO MILE (Northern) CREEK BADGER +$CREEK o! +$ REEFTON - - ALBERT ROAD Watts +$ Creek RA YANKEE JIM REEFTON - FIRELINE Mount BOUNDARY THOMSON Gregory RA - UPPER 2020-2021 TO 2022-2023 ROAD THOMSON RD McMahons Creek Aberfeldy Mt Donna Buang MOUNT E MCMAHONS E TOOLEBEWONG EAST WARBURTON CREEK - ROAD 1 Mt Useful - CORANDERRK - CROOKED +$ +$ MOUNT TOOLEBEWONG - CREEK PIPELINE+$ 60 CHAPMAN ROAD (CFA) +$ +$ +$ MCMAHONS CREEK TOOLEBEWONG - STARVATION o! EAST WARBURTON - CREEK PIPELINE MCMAHONS - CHAPMAN BRAHAMS RD PIPELINE ROAD CREEK - SMOKO RIDGE DON VALLEY - +$ 2020-21 Planned Burn (<50Ha) RIFLE RANGE Warburton Hwy Warburton Stringybark MILLGROVE - Creek RA +$ MILLGROVE 2021-22 Planned Burn (<50Ha) LAUNCHING PLACE WARBURTON HIGHWAY - LITTLE - BELLBIRD AVENUE JOE TRACK RESERVE 3 (CFA) Launching Woori Place WESBURN - Ben Cruachan +$ 2022-23 Planned Burn (<50Ha) +$ E Yallock Yarra MINESHAFT LAUNCHING PLACE - HILL -

Annual Report

1976-77 VICTORIA COUNTRY ROADS BOARD SIXTY-FOURTH ANNUAL REPORT FOR YEAR ENDED 30th JUNE, 1977 PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO ACT No. 6229 By Amhority: F. D. ATKINSON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE No. 95-10584/77-PRICE $1.10 Country Roads Board Victoria Sixty-fourth Annual Report for year ended 30th June, 1977 Presented to both Houses of Parliament pursuant to Act No. 6229 R. E. V. Donaldson Chairman T. H. Russell Deputy Chairman W S. Brake Member Principal Officers Dr. K. G. E. Moody as at 30th June, 1977 Engineer in Chief N. L. Allanson Secretary R. G. Cooper Chief Accountant N. S. Guerin Deputy Engineer in Chief C. C. Liddell Deputy Secretary R. J. C. Bulman Deputy Chief Accountant Divisional Engineers and A. N. Jephcott Regional Divisional Offices Bairnsdale E. T. Oppy Ballarat R. R. Patterson Benalla T. M. Glazebrook Bendigo S.H.Hodgson Dandenong G. W. Marshallsea Geelong J. W Heid Hors ham L. M. Jones Cover: A range of locations showing the various Metropolitan uses the Board makes of plant growth on the roadside. The Board planted 129,246 Dr. D. T. Currie trees and shrubs throughout the State during 1976-77, at a cost of $46,813. Of Traralgon the total figure. 90,471 trees and shrubs were planted within the Board's two divisions which cover Metropolitan F. G. Lodge Melbourne and its surrounds. Warrnambool Pictured are (from top to bottom): 1. Trees now established on the Ovens Highway, near Tarrawingee. 2. Creek treatment and rest area, Princes Highway East near Rosedale. -

130 Firefighters Battle Fireballs and Exploding Oil Drums

WINTER 2011 WINTER FACTORY INFERNO 130 firefighters battle fireballs and exploding oil drums ALSO: VOLUNTEER SUMMIT, CFA CONNECT REDESIGN, NEW OH&S LAWS CONTENTS ON SALE WINTER 2011 NOW! CEO’s column ......................................3 CFA news ...........................................4 Incident summary ................................5 Dandenong South factory fire ..............6 Incidents ...........................................10 Chief Officer’s column ........................16 PERFECT FATher’s DAY GIFT Brigade training .................................17 Treat your dad this Father’s Day with his own piece of CFA history: the ‘Spirit of CFA’ limited edition art print. Memberlink ......................................20 The painting, by Australian artist Jamie Cooper, shows CFA’s history from its volunteer firefighting origins to the diverse emergency services organisation it has become. Cooper has captured the essence of CFA – ordinary Australians doing Canberra Summit ..............................22 extraordinary things. The Spirit of CFA will make a special gift for your dad, grandfather and all News ................................................23 firefighting enthusiasts and will complement any home or office. Purchase this fine art print for Or framed Brigades ...........................................27 Championships ..................................31 $59.95 $195 including Australia-wide delivery Community safety .............................32 Proceeds from the sale go to leadership training for volunteers. This -

Wit.002.002.0108

WIT.002.002.0108 DEPARTMENT OF SUSTAINABILITY AND ENVIRONMENT Fire Information Chronology - 7 February 2009 00:00 to 24:00 DISCLAIMER All efforts have been made to present accurate information within this chronology. However due to the magnitude of the fires, information may be missing, incorrect or outdated. The data contained in this document has been obtained from the most appropriate sources. This document includes: 1. Fire Information Releases 2. Joint/Media Releases 3. External Web Updates 4. Radio broadcasts from ABC 774, FOX FM, MIX FM, Nova 100.3 5. Fire Behaviour Estimates 6. Total Fire Ban Notification 7. Joint State Situation Reports 8. Incident Management Logbook entries from: Ewan Waller, Alen Slijepcevic, DSE State Duty Officers, State Spokerperson and Bureau of Meteorology 9. Initial Fire Reports 10. iECC Briefing 11. State fire and resources snapshots 12. CenITex Notifications 13. Telstra Notifications 14. VBIL Updates 15. Planning and State Duty Officer Handover Notes 16. IRIS resources This document does not include: 1. Logbooks not mentioned above such as: Incident Controller, Fire Behaviour Analyst, State Aircraft Unit, iECC Planning, all regional logs. 2. Television interviews or general fire notifications 3. Regional radio 4. Fire Weather Teleconference minutes 5. Bushfire Information and Significant Incident report (BISI) as it did not occur 6. Fire and Emergency Coordination report as it did not occur 7. Forest Fire Awareness Report as it only occurs once a week This document is a factual representation of records that were generated during the fires and the information has not been altered in any way. Legend: Red text indicates an initial fire report.