Cats and Dogs in Hawaii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Pets to Companion Animals

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2001 From Pets to Companion Animals Martha C. Armstrong The Humane Society of the United States Susan Tomasello The Humane Society of the United States Christyna Hunter The Humane Society of the United States Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/sota_2001 Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, M.C., Tomasello, S., & Hunter, C. (2001). From pets to companion animals. In D.J. Salem & A.N. Rowan (Eds.), The state of the animals 2001 (pp. 71-85). Washington, DC: Humane Society Press. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Pets to Companion Animals 4CHAPTER Researched by Martha C. Armstrong, Susan Tomasello, and Christyna Hunter A Brief History of Shelters and Pounds nimal shelters in most U.S. their destiny: death by starvation, harassed working horses, pedestrians, communities bear little trace injury, gassing, or drowning. There and shopkeepers, but also spread ra- A of their historical British were no adoption, or rehoming, pro- bies and other zoonotic diseases. roots. Early settlers, most from the grams and owners reclaimed few In outlying areas, unchecked breed- British Isles, brought with them the strays. And while early humanitarians, ing of farm dogs and abandonment of English concepts of towns and town like Henry Bergh, founder of the city dwellers’ unwanted pets created management, including the rules on American Society for the Prevention packs of marauding dogs, which keeping livestock. -

Shelter Sense Volume 06, Number 08

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 10-1983 Shelter Sense Volume 06, Number 08 Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/shesen Recommended Citation "Shelter Sense Volume 06, Number 08" (1983). ShelterSense 1978-92. 24. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/shesen/24 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 6, Number 8 October 1983 Inside Help for Boards; New Dog Blood Donor Program; PAW Council Shelter Awards; New Spay/ Neuter Information For the people who care about community animal control Working hile some humane societies and municipal animal-control W agencies are unable to cooperate with each other to serve their Together in public and protect animals' welfare, the Humane Society of Wichita Wichita Falls County (Rt. 1, Box 107, Wichita Falls, TX 76301), accredited by The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), and the Animal Control Department of the Wichita Falls City-Wichita County Public by Debbie Reed Health Center (1700 Third St., Wichita Falls, TX 76301) have decidedly joined forces to accomplish their goals. "Ours has been a good relationship. Our system works," said Toni Destefano, executive director of the humane society. "Many citizens of Wichita Falls have commented about the improved animal-control services after our system went into effect. It allows more officers to be on duty on the streets, and Dr. Lanie Continued on next page J. Benson, Health Center director, and Roy Ressel, animal-control Wisconsin questionnaire to determine Wisconsin horse owners' supervisor, cooperate with us in every way. -

Health,Animal Rights,And Ecology

Health,Animal Rights,and Ecology Volume II, No.1, March 1991 ***************************************************************** PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Aloha friends, As we print this newsletter, our country is engaged in a brutal war in the Persian Gulf. It is hard for me to write something humorous about nuts and berries or tofu at such a time, so I would instead like to reprint an article written by my friend Mary Rogers, President of the Sacramento Vegetarian Society. I have made only a few minor changes in the wording. "Eating Our Way to War?" "If everyone in the U.S. were vegetarian, could we have avoided going to war in the Persian Gulf? Probably not, but absurd as it may sound on the surface, there is a connection, and it's a very simple one: animal agriculture is extremely inefficient and uses a substantial portion of our energy resources. "Cornell University economists David Fields and Robin Hur are quoted by John Robbins in Diet for a New America: 'A nationwide switch to a diet emphasizing whole grains, fresh fruits and vegetables plus limits on export of nonessential fatty foods would save enough money to cut our imported oil requirements by over 60 percent.' "Robbins also quotes Frances Moore Lappé, author of Diet for a Small Planet, who reports that 'the value of raw materials consumed to produce food from livestock is greater than the value of all oil, gas, and coal consumed in this country.' "American agriculture has become extremely energy intensive; it consumes more fossil fuel energy than it gives back in food energy, as Keith Akers states in A Vegetarian Sourcebook. -

The State of the Animals: 2001 More Than a Slap on the Wrist

Overview: The State of Animals in 2001 Paul G. Irwin he blizzard of commentary tors have taken part in a fascinating, environments; and change their inter- marking the turn of the millen- sometimes frustrating, dialogue that actions with other animals, evolving Tnium is slowly coming to an end. seeks to balance the needs of the nat- from exploitation and harm to Assessments of the past century (and, ural world with those of the world’s respect and compassion. more ambitiously, the past millenni- most dominant species—and in the Based upon that mission, The HSUS um) have ranged from the self-con- process create a truly humane society. almost fifty years after its founding gratulatory to the condemnatory. The strains created by unrestrained in 1954, “has sought to respond cre- Written from political, technological, development and accelerating harm atively and realistically to new chal- cultural, environmental, and other to the natural world make it impera- lenges and opportunities to protect perspectives, some of these commen- tive that the new century’s under- animals” (HSUS 1991), primarily taries have provided the public with standing of the word “humane” incor- through legislative, investigative, and thoughtful, uplifting analyses. At porate the insight that our human educational means. least one commentary has concluded fate is linked inextricably to that of It is only coincidentally that the that a major issue facing the United all nonhuman animals and that we choice has been made to view the States and the world is the place and all have a duty to promote active, animal condition through thoughtful plight of animals in the twenty-first steady, thorough notions of justice analysis of the past half century—the century, positing that the last few and fair treatment to animals and life span of The HSUS—rather than of decades of the twentieth century saw nonhuman nature. -

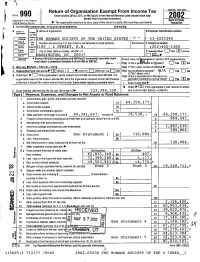

Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax °"""° I~

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax °"""° i~ Form 999 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947/a) (1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung 2002 benefit trust or private foundation) DepartmmloltheTreasury Open to public Internal He .enue servirn " The organization may have to use a copy o1 this return to satisfy state reporting requirements g~11pn A For lhe2002ealei year, or tax year period healnnina and endlna kC B cnsw n Name of organization D Employer Identification number aodhmbie use IM Monte, 1=0 -1 Y change odnt orTHE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED S "?' - " 53-02253 N . h.n, Number and street (or P 0 box d mail is not delivered to street address) Roam/style ETelephone number O2,°,m s,~n~2100 - L STREET, N.W . LVLJYJL-11VV Final Ins We ~remm ~~on. City or town sate oi country and ZIP + 4 F eaomwReeiaa 0 Cash W Accrue! ~";m°`° WASHINGTON , DC 20037 ding, ^ * Section 501(e)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts HI and I are not ~ Uceble to section 527 organizations must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ) 1uTI~ 1 H(a) Is this a prdUp'~etJrn fora~lihates? [:D Yea OX No G Web site K+7Ww .hSUS .OY' H(G) IfYes,'enter number otaffiliates " J Organization type (eeemN~l " M) 501(c) ( 3 )~41111 0hee,t no) [-_-] 4947(a)(7) Or 0 527 H(c) are an affiliates included? `iN /A ~ Yes ~ NO (it *NO,' attach a list ) 1 K Check here " = A the organization's gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 The Hid) Is this a separate return filed 4y an or- orpanization need not file a return with the IRS, but if the organization received a Form 990 Package anixaUan covered b a rou ratio ~ ~ Yes X No in the mail, it should file a return without financial data Some slates require a complete return I Enter 4-0i it GEN M Check " O A the organization is not required to attach L Gross receipts Add lines 6b, BD, 9D, and 70b to line 12 . -

The New Meatways and Sustainability

Minna Kanerva The New Meatways and Sustainability Political Science | Volume 105 This open access publication has been enabled by the support of POLLUX (Fach- informationsdienst Politikwissenschaft) and a collaborative network of academic libraries for the promotion of the Open Access transformation in the Social Sciences and Humanities (transcript Open Li- brary Politikwissenschaft 2020) This publication is compliant with the “Recommendations on quality standards for the open access provision of books”, Nationaler Open Access Kontaktpunkt 2018 (https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2932189) Universitätsbibliothek Bayreuth | Landesbibliothek | Universitätsbibliothek Universitätsbibliothek der Humboldt- Kassel | Universitäts- und Stadtbibliothek Universität zu Berlin | Staatsbibliothek Köln | Universität Konstanz, Kommuni- zu Berlin | Universitätsbibliothek FU kations-, Informations-, Medienzentrum Berlin | Universitätsbibliothek Bielefeld | Universitätsbibliothek Koblenz-Landau | (University of Bielefeld) | Universitäts- Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig | Zentral- u. bibliothek der Ruhr-Universität Bochum Hochschulbibliothek Luzern | Universitäts- | Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek | bibliothek Mainz | Universitätsbibliothek Sächsische Landesbibliothek - Staats- und Marburg | Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Universitätsbibliothek Dresden | Universi- München Universitätsbibliothek | Max tätsbibliothek Duisburg-Essen | Univer- Planck Digital Library | Universitäts- und sitäts- u. Landesbibliothek Düsseldorf | Landesbibliothek Münster | Universitäts- -

I Am a Vegetarian”: Reflections on a Aw Y of Being

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2014 “I am a Vegetarian”: Reflections on a aW y of Being Kenneth J. Shapiro Animals and Society Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_aafhh Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, and the Other Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation Shapiro, K. J. (2014). “I am a Vegetarian”: Reflections on a aW y of Being. Society & Animals, 1, 20. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I am a Vegetarian”: Reflections on a Way of Being Kenneth Joel Shapiro Animals and Society Institute [email protected] Abstract Employing a qualitative method adapted from phenomenological psychology, the paper presents a socio- psychological portrait of a vegetarian. Descriptives are a product of the author’s reflection on (dialogue with) empirical findings and published personal accounts, interviews, and case studies. The paper provides evidence for the hypothesis that vegetarianism is a way of being. This way of experiencing and living in the world is associated with particular forms of relationship to self, to other animals and nature, and to other people. The achievement of this way of being, particularly in the interpersonal sphere, comprises an initial, a transitional, and a crystallizing phase of development. The paper frames contrasts between vegetarianism and carnism through the phenomena of the presence of an absence and the absent referent, respectively. Keywords vegetarianism, qualitative analysis, phenomenology, absent referent Giehl (1975), Aronson (1996), Fox (1999), McDonald (2000), Evers (2001), Maurer (2002), and Hirschler (2009) have all suggested that, beyond the adoption of a particular dietary regimen, the psychology of vegetarianism involves a particular way of being or experiencing the world. -

State of Animals ~Index

Index Page numbers appearing in italics refer to tables or figures A pound seizure issue, 73 A-B-C model of societal attitudes, 57 Standards of Excellence program, 73 Acute Toxic Class Method, 129 training for animal control officers, 72 African Elephant Conservation Act, 156 American Kennel Club Alachua County (FL) Animal Services, 76–77 growth of registration, 78 Alternatives approach proof of spaying/neutering for pet-quality puppies, 83 1960s: dormancy of the movement, 123–124 puppy mills and, 83 1970s: animal protectionists heed the call, 125, 127 registration of dogs and puppies, 75 1980s: government and industry begin to heed the American Meat Institute Guidelines for slaughter, 106 call, 126–129 American Medical Association, animal rights poll, 58 1990s: alternatives begin to be validated and accepted American Pet Products Manufacturers Association for regulatory use, 129–131 (APPMA), survey of pet acquisition, 75 alternatives chronology: 1876–1959, 122 American Psychological Association (APA), animal alternatives chronology: 1960–1969, 123 research polls, 62, 63 alternatives chronology: 1970–1979, 125 American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to alternatives chronology: 1980–1989, 126–127 Animals (ASPCA), 7, 71, 176 alternatives chronology: 1990–1999, 130–131 American Society of Landscape Architects, 170 in the context of the animal research issue, 121–122 American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Draize Test of eye irritancy, 128 early-age sterilization, 83 five principles for animal experimentation, 122 spay/neuter clinics, 74 genetic engineering and, 133 survey of pet acquisition, 75 hostility to, 133 Angell, George Thorndike, 71 launching of the approach, 122–123 Animal abuse origin of the concept, 116, 121 balanced and restorative justice (BARJ) model, 48 Alternatives Research and Development Foundation, 117 conduct disorder and, 42–45 “Alternatives to Animal Use in Research, Testing and corporal punishment and, 43–44, 45–46 Education” report from the U.S. -

No. Caap-17-0000832 in the Intermediate Court of Appeals of the State of Hawai#I

NOT FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST'S HAWAII REPORTS OR THE PACIFIC REPORTER NO. CAAP-17-0000832 IN THE INTERMEDIATE COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF HAWAI#I STATE OF HAWAI#I, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. JAMES MONTGOMERY, Defendant-Appellee APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE FIRST CIRCUIT (CR. NO. 16-1-1076 (1PC161001076)) SUMMARY DISPOSITION ORDER (By: Leonard, Presiding Judge, Reifurth and Chan, JJ.) Plaintiff-Appellant State of Hawai#i (State) appeals from the Order Denying Hawaiian Humane Society's Requested Restitution (Order Denying Restitution), filed on October 16, 2017, in the Circuit Court of the First Circuit (circuit court).1 On July 5, 2016, Defendant-Appellee James Montgomery (Montgomery) was charged by indictment with: Count 1, Cruelty to Animals in the First Degree, in violation of Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS) § 711-1108.5(1)(a) (2014); and Count 2, Cruelty to Animals in the Second Degree, in violation of HRS § 711- 1109(1)(b) (2014). On appeal, the State contends that the circuit court erred in failing to order Montgomery to make restitution to HHS. The State challenges the following conclusions of law in the circuit court's Order Denying Restitution: 1. The Hawaiian Humane Society ("HHS") does not fall under the definition of "victim" pursuant to H.R.S. § 706- 1 The Honorable Shirley M. Kawamura presided. NOT FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST'S HAWAII REPORTS OR THE PACIFIC REPORTER 646(d) regarding the facts of this case. 2. HHS did not impound, hold, or receive custody of the animals pursuant to H.R.S. §§ 711-1109.1, 711-1109.2 or 711-1110.5. -

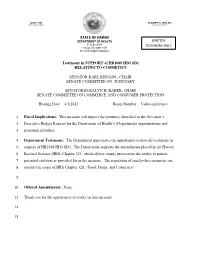

STATE of HAWAII Testimony in SUPPORT of HB1088 HD3 SD1

DAVID Y. IGE ELIZABETH A. CHAR, M.D. GOVERNOR OF HAWAII DIRECTOR OF HEALTH STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH WRITTEN P. O. Box 3378 TESTIMONY ONLY Honolulu, HI 96801-3378 [email protected] Testimony in SUPPORT of HB1088 HD3 SD1 RELATING TO COSMETICS SENATOR KARL RHOADS , CHAIR SENATE COMMITTEE ON JUDICIARY SENATOR ROSALYN H. BAKER, CHAIR SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE AND CONSUMER PROTECTION Hearing Date: 4/1/2021 Room Number: Videoconference 1 Fiscal Implications: This measure will impact the priorities identified in the Governor’s 2 Executive Budget Request for the Department of Health’s (Department) appropriations and 3 personnel priorities. 4 Department Testimony: The Department appreciates the opportunity to provide testimony in 5 support of HB1088 HD3 SD1. The Department supports the amendments placed in the Hawaii 6 Revised Statutes (HRS) Chapter 321, which allows county prosecutors the ability to pursue 7 potential violators as provided for in the measure. The regulation of cruelty-free cosmetics are 8 outside the scope of HRS Chapter 328, “Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics”. 9 10 Offered Amendments: None. 11 Thank you for the opportunity to testify on this measure. 12 13 2700 Waialae Avenue Honolulu, Hawaii 96826 808.356.2200 ● HawaiianHumane.org Date: March 29, 2021 To: Chairs Senators Karl Rhoads and Rosalyn H. Baker Vice Chairs Senators Jarrett Keohokalole and Stanley Chang and Members of the Committees on Judiciary and Commerce and Consumer Protection Submitted By: Stephanie Kendrick, Public Policy Advocate Hawaiian -

Hawaiian Humane Society CIP Redacted.Pdf

THE THIRTIETH LEGISLATURE APPLICATION FOR GRANTS CHAPTER 42F, HAWAII REVISED STATUTES Type of Grant Request: D Operating Ii) Capital Legal Name of Requesting Organization or Individual: Oba: Hawaiian Humane Society Hawaiian Humane Society Amount of State Funds Requested: $_s_oo_.o_o_o._oo____ _ Brief Description of Request (Please attach word document to back of page if extra space is needed): With the tremendous population growth in West Oahu and the animals who are both pets and homeless, the Hawaiian Humane Society (HHS) is stepping up to serve the community, and provide outreach to homeless and the animals in their care. The HHS seeks to build a facility near Old Ft. Weaver Road to be a center to welcome all animals, provide medical oversight and care, adoption opportunities, offer educational outreach and opportunities for young and old to volunteer to learn about the value to giving to their community. Amount of Other Funds Available: Total amount of State Grants Received in the Past 5 State: $300,000 Fiscal Years: ----------- $650,000 Feder a I: $__________ _ County: $_2_50_,_oo_o______ _ Unrestricted Assets: $32,469,619 Private/Other: $8,547,000----------- New Service (Presently Does Not Exist): l•I Existing Service (Presently in Operation): D Type of Business Entity: Mailing Address: l•l 501 (C)(3) Non Profit Corporation 2700 Waialae Avenue D Other Non Profit City: State: Zip: Oother Honolulu HI 96826 Contact Person for Matters Involving this Application Name: Title: Anna Neubauer President & CEO Email: Phone: [email protected] -

State of Animals Ch 04

From Pets to Companion Animals 4CHAPTER Researched by Martha C. Armstrong, Susan Tomasello, and Christyna Hunter A Brief History of Shelters and Pounds nimal shelters in most U.S. their destiny: death by starvation, harassed working horses, pedestrians, communities bear little trace injury, gassing, or drowning. There and shopkeepers, but also spread ra- A of their historical British were no adoption, or rehoming, pro- bies and other zoonotic diseases. roots. Early settlers, most from the grams and owners reclaimed few In outlying areas, unchecked breed- British Isles, brought with them the strays. And while early humanitarians, ing of farm dogs and abandonment of English concepts of towns and town like Henry Bergh, founder of the city dwellers’ unwanted pets created management, including the rules on American Society for the Prevention packs of marauding dogs, which keeping livestock. Each New England of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), and killed wildlife and livestock and posed town, for example, had a common, a George Thorndike Angell, founder of significant health risks to humans central grassy area to be used by all the Massachusetts Society for the and other animals. townspeople in any manner of bene- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals State and local governments were fit, including the grazing of livestock. (MSPCA), were concerned about ani- forced to pass laws requiring dog As long as the livestock remained on mal abuse, their focus was more on owners to control their animals. Al- the common, the animals could graze working animals—horses, in particu- though laws that prohibited deliber- at will, but once the animal strayed lar—than on the fate of stray dogs.