Race and Reflexivity 575 Quest for Certainty (1988 [1929], P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 4 Issue 4 Spring 2013 Article 5 Spring 2013 Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory Susan Archer Mann University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Mann, Susan A.. 2018. "Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 4 (Spring): 54-73. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol4/iss4/5 This Viewpoint is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory Cover Page Footnote The author wishes to thank Oxford University Press for giving her permission to draw from Chapters 1, 5, 6, 7, and the Conclusion of Doing Feminist Theory: From Modernity to Postmodernity (2012). This viewpoint is available in Journal of Feminist Scholarship: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol4/iss4/5 Mann: Third Wave Feminism's Unhappy Marriage VIEWPOINT Third Wave Feminism’s Unhappy Marriage of Poststructuralism and Intersectionality Theory Susan Archer Mann, University of New Orleans Abstract: This article first traces the history of unhappy marriages of disparate theoretical perspectives in US feminism. In recent decades, US third-wave authors have arranged their own unhappy marriage in that their major publications reflect an attempt to wed poststructuralism with intersectionality theory. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

Developing a Critical Realist Positional Approach to Intersectionality

Developing a Critical Realist Positional Approach to Intersectionality ANGELA MARTINEZ DY University of Nottingham LEE MARTIN University of Nottingham SUSAN MARLOW University of Nottingham This article identifies philosophical tensions and limitations within contemporary intersectionality theory which, it will be argued, have hindered its ability to explain how positioning in multiple social categories can affect life chances and influence the reproduction of inequality. We draw upon critical realism to propose an augmented conceptual framework and novel methodological approach that offers the potential to move beyond these debates, so as to better enable intersectionality to provide causal explanatory accounts of the ‘lived experiences’ of social privilege and disadvantage. KEYWORDS critical realism, critique, feminism, intersectionality, methodology, ontology Introduction Intersectionality has emerged over the past thirty years as an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing the concurrent impacts of social structures, with a focus on theorizing how belonging to multiple exclusionary social categories can influence political access and equality.1 It conceptualizes the interaction of categories of difference such as gender, race and class at many levels, including individual experience, social practices, institutions and ideologies, and frames the outcomes of these interactions in terms of the distribution and allocation of power.2 As a form of social critique originally rooted in black feminism,3 intersectionality is described by Jennifer -

Curriculum Vitae

David Geronimo Truc-Thanh Embrick Work Department of Sociology Africana Studies Institute Address University of Connecticut University of Connecticut Manchester Hall, #224 241 Glenbrook Road 344 Mansfield Road Unit 4162 Storrs, CT 06269 Storrs, CT 06269 Email: [email protected] Office # 860-486-8003 Alt Email: [email protected] Birthplace Fort Riley, Kansas ACADEMIC TRAINING 2006 PhD, Sociology, Texas A&M University (dissertation defended with distinction). 2003 Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies, Texas A&M University 2002 MS, Sociology, Texas A&M University 1999 BS, Sociology, Texas A&M University 1999 Certificate in Ethnic Relations, Texas A&M University 1996 AS, Business, Blinn College 1993 AAS, Criminal Justice, Central Texas College ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2016-current Associate Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies, University of Connecticut Core Faculty: Race, Ethnicity, and Politics (Political Science Department) Affiliate: El Instituto Affiliate: Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP) 2012-2016 Associate Professor of Sociology, Loyola University Chicago1 Affiliate: Black World Studies Affiliate: Latin American and Latino/a Studies Affiliate: Peace Studies 2006-2012 Assistant Professor of Sociology, Loyola University Chicago 2004-2005 Assistant Lecturer, Department of Sociology, Texas A&M University 2003-2006 Sociology Instructor, Blinn College VISITING PROFESSORSHIPS and OTHER HONORIFICS 2017-2018 Senior Research Specialist; Institute on Race Relations and Public Policy (IRRPP), -

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of Its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueck

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner Working Paper # 0012 January 2018 Division of Social Science Working Paper Series New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island P.O Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, UAE https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/academics/divisions/social-science.html 1 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo Yale University [email protected] Julia Adams Yale University [email protected] Hannah Brueckner NYU-Abu Dhabi [email protected] Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge support for this research from the National Science Foundation (grant #1322971), research assistance from Yasmin Kakar, and comments from Scott Boorman, anonymous reviewers, participants in the Comparative Research Workshop at Yale Sociology, as well as from panelists and audience members at the Social Science History Association. 2 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner “People just don't vanish and so forth.” “But she has.” “What?” “Vanished.” “Who?” “The old dame.” … “But how could she?” “What?” “Vanish.” “I don't know.” “That just explains my point. People just don't disappear into thin air.” --- Alfred Hitchcock, The Lady Vanishes (1938)1 INTRODUCTION In comparison to many academic disciplines, sociology has been relatively open to women since its founding, and seems increasingly so. Yet many notable female sociologists are missing from the public history of American sociology, both print and digital. The rise of crowd- sourced digital sources, particularly the largest and most influential, Wikipedia, seems to promise a new and more welcoming approach. -

Public Sociologies / 1603 Public Sociologies: Contradictions, Dilemmas, and Possibilities*

Public Sociologies / 1603 Public Sociologies: Contradictions, Dilemmas, and Possibilities* MICHAEL BURAWOY, University of California, Berkeley Abstract The growing interest in public sociologies marks an increasing gap between the ethos of sociologists and social, political, and economic tendencies in the wider society. Public sociology aims to enrich public debate about moral and political issues by infusing them with sociological theory and research. It has to be distinguished from policy, professional, and critical sociologies. Together these four interdependent sociologies enter into relations of domination and subordination, forming a disciplinary division of labor that varies among academic institutions as well as over time, both within and between nations. Applying the same disciplinary matrix to the other social sciences suggests that sociology’s specific contribution lies in its relation to civil society, and, thus, in its defense of human interests against the encroachment of states and markets. In 2003 the members of the American Sociological Association (ASA) were asked to vote on a member resolution opposing the war in Iraq. The resolution included the following justification: “[F]oreign interventions that do not have the support of the world community create more problems than solutions . Instead of lessening the risk of terrorist attacks, this invasion could serve as the spark for multiple attacks in years to come.” It passed by a two thirds majority (with 22% of voting members abstaining) and became the association’s official position. In an opinion poll on the same ballot, 75% of the members who expressed an opinion were opposed to the war. To assess the ethos of sociologists * This article was the basis of my address to the North Carolina Sociological Association, March 5, 2004. -

Alice Fothergill

ALICE FOTHERGILL University of Vermont, Department of Sociology, 31 South Prospect Street, Burlington, Vermont 05405 (802) 656-2127 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 2001 Ph.D. Sociology, University of Colorado at Boulder, with distinction 1989 B.A. Sociology, University of Vermont, Magna Cum Laude 1987 State University of New York at Catholic University, Lima, Peru ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2017 Fulbright Fellowship, Joint Centre for Disaster Research, Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand 2017- Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2008-2017 Associate Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2003-2008 Assistant Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2001-2003 Assistant Professor, University of Akron, Department of Sociology 1994-1999 Research Assistant, Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado 1998 Adjunct Faculty, Regis University, Denver, Department of Sociology 1997-2000 Graduate Instructor, University of Colorado, Department of Sociology AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Sociology of Disaster, Children & Youth, Family, Gender, Qualitative Methods, Inequality, Service Learning BOOKS Alice Fothergill and Lori Peek. 2015. Children of Katrina. Austin: University of Texas Press. * *Winner of the Outstanding Scholarly Contribution (Book) Award, American Sociological Association Children and Youth Section, 2016 *Winner of the Betty and Alfred McClung Lee Book Award, Association for Humanist Sociology, 2016 *Honorable Mention, Leo Goodman Award for the American Sociological Association Methodology Section 2016. * Finalist, Colorado Book Awards, 2016 *Selected as Outstanding Academic Title by Choice magazine, Association of College and Research Libraries/American Library Association), 2017 Deborah S.K. Thomas, Brenda D. Phillips, William E. Lovekamp, Alice Fothergill, Editors. 2013. Social Vulnerability to Disasters: 2nd Edition. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis. -

The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader Intellectual and Political Controversies

The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader Intellectual and Political Controversies Edited by Sandra Harding '; c ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK AND LONDON Published in 2004 by Routledge CONTENTS 29 West 35th Street New York, New York 10001 Acknowledgments IX www.routledge-ny.com Permissions xi Published in Great Britain by Routledge 1. Introduction: Standpoint Theory as a Site of Political, 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE Philosophic, and Scientific Debate www.routledge.co.uk SANDRA HARDING Copyright © 2004 by Routledge I. The Logic of a Standpoint 17 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. 2. Women's Perspective as a Radical Critique of Sociology 21 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. DOROTHY E. SMITH All rights reserved. No part of this book maybe reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any 3. The Feminist Standpoint: Developing the Ground for form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, a Specifically Feminist Historical Materialism 35 including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. NANCY C. M. HARTSOCK 4. Feminist Politics and Epistemology: The Standpoint 10 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 of Women 55 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data ALISON M. JAGGAR The feminist standpoint theory reader : intellectual and political 5. Hand, Brain, and Heart: A Feminist Epistemology controversies / edited by Sandra Harding. for the Natural Sciences 67 p. cm. HILARY ROSE Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-415-94500-3 (alk. paper)—ISBN 0-415-94501-1 (pbk.: alk. -

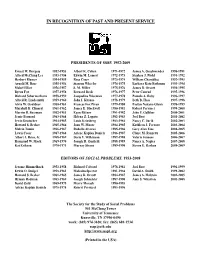

In Recognition of Past and Present Service

IN RECOGNITION OF PAST AND PRESENT SERVICE PRESIDENTS OF SSSP, 1952-2009 Ernest W. Burgess 1952-1953 Albert K. Cohen 1971-1972 James A. Geschwender 1990-1991 Alfred McClung Lee 1953-1954 Edwin M. Lemert 1972-1973 Stephen J. Pfohl 1991-1992 Herbert Blumer 1954-1955 Rose Coser 1973-1974 William Chambliss 1992-1993 Arnold M. Rose 1955-1956 Stanton Wheeler 1974-1975 Barbara Katz Rothman 1993-1994 Mabel Elliot 1956-1957 S. M. Miller 1975-1976 James D. Orcutt 1994-1995 Byron Fox 1957-1958 Bernard Beck 1976-1977 Peter Conrad 1995-1996 Richard Schermerhorn 1958-1959 Jacqueline Wiseman 1977-1978 Pamela A. Roby 1996-1997 Alfred R. Lindesmith 1959-1960 John I. Kitsuse 1978-1979 Beth B. Hess 1997-1998 Alvin W. Gouldner 1960-1961 Frances Fox Piven 1979-1980 Evelyn Nakano Glenn 1998-1999 Marshall B. Clinard 1961-1962 James E. Blackwell 1980-1981 Robert Perrucci 1999-2000 Marvin B. Sussman 1962-1963 Egon Bittner 1981-1982 John F. Galliher 2000-2001 Jessie Bernard 1963-1964 Helena Z. Lopata 1982-1983 Joel Best 2001-2002 Irwin Deutscher 1964-1965 Louis Kriesberg 1983-1984 Nancy C. Jurik 2002-2003 Howard S. Becker 1965-1966 Joan W. Moore 1984-1985 Kathleen J. Ferraro 2003-2004 Melvin Tumin 1966-1967 Rodolfo Alvarez 1985-1986 Gary Alan Fine 2004-2005 Lewis Coser 1967-1968 Arlene Kaplan Daniels 1986-1987 Claire M. Renzetti 2005-2006 Albert J. Reiss, Jr. 1968-1969 Doris Y. Wilkinson 1987-1988 Valerie Jenness 2006-2007 Raymond W. Mack 1969-1970 Joseph R. Gusfield 1988-1989 Nancy A. -

SWS Network News – Fall 2014

I N S I D E Network news T H I S ISSUE: NETWORK NEWS OCTOBER 2014 Reports from 1 the Leadership As the new academic year gets under- Education”; “Gender and Sci- way, it’s time to mark your calendars ence”; “International Perspectives on Membership 5 for the upcoming Winter Meeting: Feminist Sociology”; “Global Femi- drive nist Partnerships”; “The Politics of Executive 7 FEMINISM IN THEORY, Paid Family Leave”; “Women and Office PRACTICE, AND POLICY Health”; and “Writing for Feminist Sociologists.” Session 9 February 19 - 22, 2015 summaries * Roundtables, poster sessions, new Washington, DC book exhibits, and mentoring sessions. Awards 11 Our meeting theme draws on SWS’s * A wide range of committee meet- G & S in the 20 historic mission to contribute to posi- ings, where the work of building the Classroom tive change for women, both in the organization, pursuing ongoing pro- academy and in society. We’ve chosen jects, and developing new initiatives Chapter 27 DC to highlight our goal of melding takes place Updates sociological insight with real-world ac- tivism and are now hard at work devel- * Lots of opportunities to see old Members 30 friends and make new ones at recep- Bookshelf oping the program. Here’s an early re- port on how things are shaping up: tions, coffee breaks, the banquet and auction, and other events for socializ- * A lineup of plenaries that includes ing, networking, and just hanging out. Global 33 “Building Feminist and Women’s Or- Feminist ganizations”; “The Gender Revolution: We’re enthusiastic about this lineup of Partnership Where are We Now?”; “Gender and panels, workshops, and activities. -

OK, Erving, I Am Sending Over a Reporter"

Bios Sociologicus: The Erving Goffman Archives Center for Democratic Culture 5-19-2009 Had the New President, So I Said, "OK, Erving, I Am Sending Over a Reporter" Russell Dynes University of Delaware Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/goffman_archives Part of the Politics and Social Change Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Repository Citation Dynes, R. (2009). Had the New President, So I Said, "OK, Erving, I Am Sending Over a Reporter". In Dmitri N. Shalin, Bios Sociologicus: The Erving Goffman Archives 1-17. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/goffman_archives/18 This Interview is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Interview in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Interview has been accepted for inclusion in Bios Sociologicus: The Erving Goffman Archives by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remembering Erving Goffman Russell Dynes: Had the New President, So I Said, "OK, Erving, I Am Sending Over a Reporter" This interview with Russell Dynes, professor emeritus at the Universityof Delaware, was recorded over the phone on February 4, 2009. Dmitri Shalin transcribed the interview, after which Dr. -

Toward a Humanistic Sociological Theory

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete.