Toward a Humanistic Sociological Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialectical Self-Overcoming and the Concept of Resilience

“Think You Right: I Am Not What I Am”: Dialectical Self-Overcoming and the Concept of Resilience Benjamin B. Taylor Department of Political Science, John Hopkins University, [email protected] Abstract: In this paper, I argue that “resilience” in some sense of the term is a necessary predicate of all subjectivity, and thus of all political programs subjects could be capable of undertaking. While contemporary political discourses typically call for “resilience” as a way to justify the social formations already in place, this does not mean that the concept of resilience is itself irredeemable. In fact, all subjects must first be “resilient,” i.e., continue to exist as themselves in some sense, before they can aspire to be other than what they are. Consequently, we cannot totally abandon the concept, even as we must continue to examine with suspicion the ways those in authority deploy it to secure their rule. I contend that the term “resilience” embodies—etymologically and socially—the classical tension between “being” and “becoming” that lies at the root of dialectical thought. By framing resilience in terms of dialectical thinking, we can see how it is both necessary for and dangerous to the pursuit of a robust and imaginative politics, as well as to ethical projects of self-mastery and self-creation. Keywords: Resilience, Dialectics, Critical Theory, Foucault, Machiavelli, Nietzschean Ethics, Self-Mastery Introduction The call for papers that SPECTRA advertised for this volume was titled “critiques of resilience.” The rest of the call elaborated on the sense of “critique” in the title by explaining that the editors were seeking papers “critically engage[d] with the notion of resilience by way of integrating theoretical, empirical, literary, and ethnographic research.” What this makes apparent is that the editors were not merely in want of a ruthless criticism of the concept of resilience aimed at eviscerating it until it had been proved devoid of any value. -

CRITICAL THEORY Past, Present, Future Anders Bartonek and Sven-Olov Wallensein (Eds.) SÖDERTÖRN PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES

CRITICAL THEORY Past, Present, Future Anders Bartonek and Sven-Olov Wallensein (eds.) SÖDERTÖRN PHILOSOPHICAL STUDIES The series is attached to Philosophy at Sder- trn University. Published in the series are es- says as well as anthologies, with a particular em- phasis on the continental tradition, understood in its broadest sense, from German idealism to phenomenology, hermeneutics, critical theory and contemporary French philosophy. The com- mission of the series is to provide a platform for the promotion of timely and innovative phil- osophical research. Contributions to the series are published in English or Swedish. Cover image: Kristofer Nilson, System (Portrait of a Swedish Tax Form), 2020, Lead pencil drawing on chalk paint, on mdf 59.2 x 42 cm. Photo: Jesper Petersen. Te Swedish tax form is one of many systems designed to handle and present information. Mapped onto the surface of an artwork, it opens a free space; an untouched surface where everything can exist at the same time. Kristofer Nilson Critical Theory Past, Present, Future Edited by Anders Bartonek & Sven-Olov Wallenstein Sdertrns hgskola Sdertrns University Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © the Authors Published under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License Cover layout: Jonathan Robson Graphic form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2021 Sdertrn Philosophical Studies 28 ISSN 1651-6834 Sdertrn Academic Studies 83 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-89109-35-3 (print) ISBN 978-91-89109-36-0 (digital) Contents Introduction -

Modelling Communities and Populations: an Introduction to Computational Social Science

STUDIA METODOLOGICZNE NR 39 • 2019, 123–152 DOI: 10.14746/sm.2019.39.5 Andrzej Jarynowski, Michał B. Paradowski, Andrzej Buda Modelling communities and populations: An introduction to computational social science Abstract. In sociology, interest in modelling has not yet become widespread. However, the methodology has been gaining increased attention in parallel with its growing popularity in economics and other social sciences, notably psychology and political science, and the growing volume of social data being measured and collected. In this paper, we present representative computational methodologies from both data-driven (such as “black box”) and rule-based (such as “per analogy”) approaches. We show how to build simple models, and discuss both the greatest successes and the major limitations of modelling societies. We claim that the end goal of computational tools in sociology is providing meaningful analyses and calculations in order to allow making causal statements in sociological ex- planation and support decisions of great importance for society. Keywords: computational social science, mathematical modelling, sociophysics, quantita- tive sociology, computer simulations, agent-based models, social network analysis, natural language processing, linguistics. 1. One model of society, but many definitions Social reality has been a fascinating area for mathematical description for a long time. Initially, many mathematical models of social phenomena resulted in simplifications of low application value. However, with their grow- ing validity (in part due to constantly increasing computing power allowing for increased multidimensionality), they have slowly begun to be applied in prediction and forecasting (social engineering), given that the most interesting feature of social science research subjects – people, organisations, or societies – is their complexity, usually based on non-linear interactions. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Communism with Its Clothes Off: Eastern European Film Comedy and the Grotesque A Dissertation Presented by Lilla T!ke to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Lilla T!ke 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Lilla T!ke We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. E. Ann Kaplan, Distinguished Professor, English and Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies, Dissertation Director Krin Gabbard, Professor, Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies, Chairperson of Defense Robert Harvey, Professor, Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies and European Languages Sandy Petrey, Professor, Comparative Literary and Cultural Studies and European Languages Katie Trumpener, Professor, Comparative Literature and English, Yale University Outside Reader This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Communism with Its Clothes Off: Eastern European Film Comedy and the Grotesque by Lilla T!ke Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature Stony Brook University 2010 The dissertation examines the legacies of grotesque comedy in the cinemas of Eastern Europe. The absolute non-seriousness that characterized grotesque realism became a successful and relatively safe way to talk about the absurdities and the failures of the communist system. This modality, however, was not exclusive to the communist era but stretched back to the Austro-Hungarian era and forward into the Postcommunist times. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

Transpersonal Sociology: Origins, Development, and Theory Ryan Rominger Sofia University

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 32 | Issue 2 Article 5 7-1-2013 Transpersonal Sociology: Origins, Development, and Theory Ryan Rominger Sofia University Harris L. Friedman University of Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, Religion Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Rominger, R., & Friedman, H. L. (2013). Rominger, R., & Freidman, H. (2013). Transpersonal sociology: Origins, development, and theory. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 32(2), 17–33.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 32 (2). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2013.32.2.17 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transpersonal Sociology: Origins, Development, and Theory Ryan Rominger1 Harris Friedman Sofia University University of Florida Palo Alto, CA, USA Gainesville, FL, USA Transpersonal theory formally developed within psychology through the initial definition of the field in the publishing of the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. However, transpersonal sociology also developed with the Transpersonal Sociology Newsletter, which operated through the middle 1990s. Both disciplines have long histories, while one continues to flourish and the other, comparatively, is languishing. In order to encourage renewed interest in this important area of transpersonal studies, we discuss the history, and further define the field of transpersonal sociology, discuss practical applications of transpersonal sociology, and introduce research approaches that might be of benefit for transpersonal sociological researchers and practitioners. -

Curriculum Vitae

David Geronimo Truc-Thanh Embrick Work Department of Sociology Africana Studies Institute Address University of Connecticut University of Connecticut Manchester Hall, #224 241 Glenbrook Road 344 Mansfield Road Unit 4162 Storrs, CT 06269 Storrs, CT 06269 Email: [email protected] Office # 860-486-8003 Alt Email: [email protected] Birthplace Fort Riley, Kansas ACADEMIC TRAINING 2006 PhD, Sociology, Texas A&M University (dissertation defended with distinction). 2003 Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies, Texas A&M University 2002 MS, Sociology, Texas A&M University 1999 BS, Sociology, Texas A&M University 1999 Certificate in Ethnic Relations, Texas A&M University 1996 AS, Business, Blinn College 1993 AAS, Criminal Justice, Central Texas College ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2016-current Associate Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies, University of Connecticut Core Faculty: Race, Ethnicity, and Politics (Political Science Department) Affiliate: El Instituto Affiliate: Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP) 2012-2016 Associate Professor of Sociology, Loyola University Chicago1 Affiliate: Black World Studies Affiliate: Latin American and Latino/a Studies Affiliate: Peace Studies 2006-2012 Assistant Professor of Sociology, Loyola University Chicago 2004-2005 Assistant Lecturer, Department of Sociology, Texas A&M University 2003-2006 Sociology Instructor, Blinn College VISITING PROFESSORSHIPS and OTHER HONORIFICS 2017-2018 Senior Research Specialist; Institute on Race Relations and Public Policy (IRRPP), -

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of Its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueck

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner Working Paper # 0012 January 2018 Division of Social Science Working Paper Series New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island P.O Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, UAE https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/academics/divisions/social-science.html 1 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo Yale University [email protected] Julia Adams Yale University [email protected] Hannah Brueckner NYU-Abu Dhabi [email protected] Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge support for this research from the National Science Foundation (grant #1322971), research assistance from Yasmin Kakar, and comments from Scott Boorman, anonymous reviewers, participants in the Comparative Research Workshop at Yale Sociology, as well as from panelists and audience members at the Social Science History Association. 2 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner “People just don't vanish and so forth.” “But she has.” “What?” “Vanished.” “Who?” “The old dame.” … “But how could she?” “What?” “Vanish.” “I don't know.” “That just explains my point. People just don't disappear into thin air.” --- Alfred Hitchcock, The Lady Vanishes (1938)1 INTRODUCTION In comparison to many academic disciplines, sociology has been relatively open to women since its founding, and seems increasingly so. Yet many notable female sociologists are missing from the public history of American sociology, both print and digital. The rise of crowd- sourced digital sources, particularly the largest and most influential, Wikipedia, seems to promise a new and more welcoming approach. -

Timcke Triplec2

tripleC 11(2): 375-387, 2013 http://www.triple-c.at Is All Reification Forgetting?: On Connerton’s Types of For- getting Scott Timcke School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada, [email protected] Abstract: Drawing upon early the Frankfurt School tradition, I offer a qualified defence of Connerton’s version of collective forgetting against recent detractors. This defence pertains strictly to the material culture aspects of collective forgetting. In this respect, the paper argues that models of individual and collective memory must attend to the historical forces that combine to (re)produce a particular envi- ronment, and further, they should consider the subsequent role the reproduction process plays on triggering moments of recollection or collective memory actions. To explicate this claim, I draw upon a Marxist inspired account of the labour process to show that variations in types of consciousness are related to particular modes of production. It is my intent to explicate Connerton’s theoretical reasoning such that readers from diverse backgrounds are better informed about his underlying set of assump- tions. In this respect, this paper aims to contributing notes towards a political economy of memory. Keywords: Memory, Labour Process, Reification, Forgetting, Critical Theory, Paul Connerton Acknowledgement: Thanks to Rick Gruneau and Jan Marontate for assistance. The journal Memory Studies was established in 2008 to afford recognition to and provide a “critical forum” for the plural study of collective memory (Hoskins, et al 2008). Included in the inaugural issue was an article written by Paul Connerton, a well-known social anthropologist, which could be thought to go against the grain of the implied editorial objectives. -

Public Sociologies / 1603 Public Sociologies: Contradictions, Dilemmas, and Possibilities*

Public Sociologies / 1603 Public Sociologies: Contradictions, Dilemmas, and Possibilities* MICHAEL BURAWOY, University of California, Berkeley Abstract The growing interest in public sociologies marks an increasing gap between the ethos of sociologists and social, political, and economic tendencies in the wider society. Public sociology aims to enrich public debate about moral and political issues by infusing them with sociological theory and research. It has to be distinguished from policy, professional, and critical sociologies. Together these four interdependent sociologies enter into relations of domination and subordination, forming a disciplinary division of labor that varies among academic institutions as well as over time, both within and between nations. Applying the same disciplinary matrix to the other social sciences suggests that sociology’s specific contribution lies in its relation to civil society, and, thus, in its defense of human interests against the encroachment of states and markets. In 2003 the members of the American Sociological Association (ASA) were asked to vote on a member resolution opposing the war in Iraq. The resolution included the following justification: “[F]oreign interventions that do not have the support of the world community create more problems than solutions . Instead of lessening the risk of terrorist attacks, this invasion could serve as the spark for multiple attacks in years to come.” It passed by a two thirds majority (with 22% of voting members abstaining) and became the association’s official position. In an opinion poll on the same ballot, 75% of the members who expressed an opinion were opposed to the war. To assess the ethos of sociologists * This article was the basis of my address to the North Carolina Sociological Association, March 5, 2004. -

Alice Fothergill

ALICE FOTHERGILL University of Vermont, Department of Sociology, 31 South Prospect Street, Burlington, Vermont 05405 (802) 656-2127 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 2001 Ph.D. Sociology, University of Colorado at Boulder, with distinction 1989 B.A. Sociology, University of Vermont, Magna Cum Laude 1987 State University of New York at Catholic University, Lima, Peru ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2017 Fulbright Fellowship, Joint Centre for Disaster Research, Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand 2017- Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2008-2017 Associate Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2003-2008 Assistant Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2001-2003 Assistant Professor, University of Akron, Department of Sociology 1994-1999 Research Assistant, Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado 1998 Adjunct Faculty, Regis University, Denver, Department of Sociology 1997-2000 Graduate Instructor, University of Colorado, Department of Sociology AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Sociology of Disaster, Children & Youth, Family, Gender, Qualitative Methods, Inequality, Service Learning BOOKS Alice Fothergill and Lori Peek. 2015. Children of Katrina. Austin: University of Texas Press. * *Winner of the Outstanding Scholarly Contribution (Book) Award, American Sociological Association Children and Youth Section, 2016 *Winner of the Betty and Alfred McClung Lee Book Award, Association for Humanist Sociology, 2016 *Honorable Mention, Leo Goodman Award for the American Sociological Association Methodology Section 2016. * Finalist, Colorado Book Awards, 2016 *Selected as Outstanding Academic Title by Choice magazine, Association of College and Research Libraries/American Library Association), 2017 Deborah S.K. Thomas, Brenda D. Phillips, William E. Lovekamp, Alice Fothergill, Editors. 2013. Social Vulnerability to Disasters: 2nd Edition. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis. -

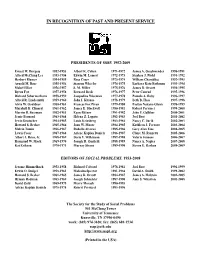

In Recognition of Past and Present Service

IN RECOGNITION OF PAST AND PRESENT SERVICE PRESIDENTS OF SSSP, 1952-2009 Ernest W. Burgess 1952-1953 Albert K. Cohen 1971-1972 James A. Geschwender 1990-1991 Alfred McClung Lee 1953-1954 Edwin M. Lemert 1972-1973 Stephen J. Pfohl 1991-1992 Herbert Blumer 1954-1955 Rose Coser 1973-1974 William Chambliss 1992-1993 Arnold M. Rose 1955-1956 Stanton Wheeler 1974-1975 Barbara Katz Rothman 1993-1994 Mabel Elliot 1956-1957 S. M. Miller 1975-1976 James D. Orcutt 1994-1995 Byron Fox 1957-1958 Bernard Beck 1976-1977 Peter Conrad 1995-1996 Richard Schermerhorn 1958-1959 Jacqueline Wiseman 1977-1978 Pamela A. Roby 1996-1997 Alfred R. Lindesmith 1959-1960 John I. Kitsuse 1978-1979 Beth B. Hess 1997-1998 Alvin W. Gouldner 1960-1961 Frances Fox Piven 1979-1980 Evelyn Nakano Glenn 1998-1999 Marshall B. Clinard 1961-1962 James E. Blackwell 1980-1981 Robert Perrucci 1999-2000 Marvin B. Sussman 1962-1963 Egon Bittner 1981-1982 John F. Galliher 2000-2001 Jessie Bernard 1963-1964 Helena Z. Lopata 1982-1983 Joel Best 2001-2002 Irwin Deutscher 1964-1965 Louis Kriesberg 1983-1984 Nancy C. Jurik 2002-2003 Howard S. Becker 1965-1966 Joan W. Moore 1984-1985 Kathleen J. Ferraro 2003-2004 Melvin Tumin 1966-1967 Rodolfo Alvarez 1985-1986 Gary Alan Fine 2004-2005 Lewis Coser 1967-1968 Arlene Kaplan Daniels 1986-1987 Claire M. Renzetti 2005-2006 Albert J. Reiss, Jr. 1968-1969 Doris Y. Wilkinson 1987-1988 Valerie Jenness 2006-2007 Raymond W. Mack 1969-1970 Joseph R. Gusfield 1988-1989 Nancy A.