OK, Erving, I Am Sending Over a Reporter"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Tradition in Qualitative Research

SAGE BENCHMARKS IN RESEARCH METHODS THE AMERICAN TRADITION IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH VOLUME I EDITED BY NORMAN K. DENZIN YVONNA S. LINCOLN SAGE Publications London • Thousand Oaks • New Delhi CONTENTS VOLUME I Appendix of Sources I Editors' Introduction xi PART ONE HISTORY, ETHICS, POLITICS AND PARADIGMS OF INQUIRY Section One History and Ethics 1. Qualitative Methods: Their History in Sociology and Anthropology Arthur J. Vidich & Stanford M. Lyman 3 2. Action Anthropology Sol Tax 62 3. Whose Side Are We On? Howard S. Becker 71 4. Black Bourgeoisie: Public and Academic Reactions E. Franklin Frazier 82 5. Sociological Snoopers and Journalistic Moralizers: An Exchange Nicholas von Hoffman 88 6. Ethics: The Failure of Positivist Science Yvonna S. Lincoln &Egon G. Guba 92 7. Emerging Criteria for Quality in Qualitative and Interpretive Research Yvonna S. Lincoln 108 Section Two Positivism, Postpositivism and Constructivism 8. Methodological Principles of Empirical Science Herbert Blumer 122 9. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective Donna Haraway 128 Section Three Feminism, Racialized Discourse, Critical Theory 10. Criteria of Negro Art W.E.B.DuBois 149 11. Research Zora Neale Hurston 157 12. A Blueprint for Negro Authors Nick Aaron Ford 173 13. An American Dilemma: A Review Ralph Ellison 177 14. The Homeland Aztland and Movimientos de Rebeldia y las Culturas que Traicionan Gloria Anzaldua 186 15. Toward an Afrocentric Feminist Epistemology Patricia Hill Collins 195 16. Saving Black Folk Culture: Zora Neale Hurston as Anthropologist and Writer bell hooks 215 17. The Black Arts Movement Larry Neal 223 18. Coloring Epistemologies: Are Our Research Epistemologies Racially Biased? James Joseph Scheurich & Michelle D. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

Curriculum Vitae

David Geronimo Truc-Thanh Embrick Work Department of Sociology Africana Studies Institute Address University of Connecticut University of Connecticut Manchester Hall, #224 241 Glenbrook Road 344 Mansfield Road Unit 4162 Storrs, CT 06269 Storrs, CT 06269 Email: [email protected] Office # 860-486-8003 Alt Email: [email protected] Birthplace Fort Riley, Kansas ACADEMIC TRAINING 2006 PhD, Sociology, Texas A&M University (dissertation defended with distinction). 2003 Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies, Texas A&M University 2002 MS, Sociology, Texas A&M University 1999 BS, Sociology, Texas A&M University 1999 Certificate in Ethnic Relations, Texas A&M University 1996 AS, Business, Blinn College 1993 AAS, Criminal Justice, Central Texas College ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2016-current Associate Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies, University of Connecticut Core Faculty: Race, Ethnicity, and Politics (Political Science Department) Affiliate: El Instituto Affiliate: Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP) 2012-2016 Associate Professor of Sociology, Loyola University Chicago1 Affiliate: Black World Studies Affiliate: Latin American and Latino/a Studies Affiliate: Peace Studies 2006-2012 Assistant Professor of Sociology, Loyola University Chicago 2004-2005 Assistant Lecturer, Department of Sociology, Texas A&M University 2003-2006 Sociology Instructor, Blinn College VISITING PROFESSORSHIPS and OTHER HONORIFICS 2017-2018 Senior Research Specialist; Institute on Race Relations and Public Policy (IRRPP), -

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of Its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueck

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner Working Paper # 0012 January 2018 Division of Social Science Working Paper Series New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island P.O Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, UAE https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/academics/divisions/social-science.html 1 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo Yale University [email protected] Julia Adams Yale University [email protected] Hannah Brueckner NYU-Abu Dhabi [email protected] Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge support for this research from the National Science Foundation (grant #1322971), research assistance from Yasmin Kakar, and comments from Scott Boorman, anonymous reviewers, participants in the Comparative Research Workshop at Yale Sociology, as well as from panelists and audience members at the Social Science History Association. 2 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner “People just don't vanish and so forth.” “But she has.” “What?” “Vanished.” “Who?” “The old dame.” … “But how could she?” “What?” “Vanish.” “I don't know.” “That just explains my point. People just don't disappear into thin air.” --- Alfred Hitchcock, The Lady Vanishes (1938)1 INTRODUCTION In comparison to many academic disciplines, sociology has been relatively open to women since its founding, and seems increasingly so. Yet many notable female sociologists are missing from the public history of American sociology, both print and digital. The rise of crowd- sourced digital sources, particularly the largest and most influential, Wikipedia, seems to promise a new and more welcoming approach. -

Public Sociologies / 1603 Public Sociologies: Contradictions, Dilemmas, and Possibilities*

Public Sociologies / 1603 Public Sociologies: Contradictions, Dilemmas, and Possibilities* MICHAEL BURAWOY, University of California, Berkeley Abstract The growing interest in public sociologies marks an increasing gap between the ethos of sociologists and social, political, and economic tendencies in the wider society. Public sociology aims to enrich public debate about moral and political issues by infusing them with sociological theory and research. It has to be distinguished from policy, professional, and critical sociologies. Together these four interdependent sociologies enter into relations of domination and subordination, forming a disciplinary division of labor that varies among academic institutions as well as over time, both within and between nations. Applying the same disciplinary matrix to the other social sciences suggests that sociology’s specific contribution lies in its relation to civil society, and, thus, in its defense of human interests against the encroachment of states and markets. In 2003 the members of the American Sociological Association (ASA) were asked to vote on a member resolution opposing the war in Iraq. The resolution included the following justification: “[F]oreign interventions that do not have the support of the world community create more problems than solutions . Instead of lessening the risk of terrorist attacks, this invasion could serve as the spark for multiple attacks in years to come.” It passed by a two thirds majority (with 22% of voting members abstaining) and became the association’s official position. In an opinion poll on the same ballot, 75% of the members who expressed an opinion were opposed to the war. To assess the ethos of sociologists * This article was the basis of my address to the North Carolina Sociological Association, March 5, 2004. -

Great Divides: the Cultural, Cognitive, and Social Bases of the Global Subordination of Women

2006 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Great Divides: The Cultural, Cognitive, and Social Bases of the Global Subordination of Women Cynthia Fuchs Epstein Graduate Center, City University of New York Categorization based on sex is the most basic social divide. It is the organizational basis of most major institutions, including the division of labor in the home, the workforce, politics, and religion. Globally, women’s gendered roles are regarded as subordinate to men’s. The gender divide enforces women’s roles in reproduction and support activities and limits their autonomy, it limits their participation in decision making and highly-rewarded roles, and it puts women at risk. Social, cultural, and psychological mechanisms support the process. Differentiation varies with the stability of groups and the success of social movements. Gender analyses tend to be ghettoized; so it is recommended that all sociologists consider gender issues in their studies to better understand the major institutions and social relation- ships in society. he world is made up of great divides— social boundaries as well (Gerson and Peiss Tdivides of nations, wealth, race, religion, 1985; Lamont and Molnar 2002). Today, as in education, class, gender, and sexuality—all con- the past, these constructs not only order social structs created by human agency. The concep- existence, but they also hold the capacity to create serious inequalities, generate conflicts, tual boundaries that define these categories are and promote human suffering. In this address, always symbolic and may create physical and I argue that the boundary based on sex creates the most fundamental social divide—a divide Direct correspondence to Cynthia Fuchs Epstein, Department of Sociology, Graduate Center, City rial help over many incarnations of this paper and to University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, New Kathleen Gerson, Jerry Jacobs, Brigid O’Farrell, York, NY 10016 ([email protected]). -

Alice Fothergill

ALICE FOTHERGILL University of Vermont, Department of Sociology, 31 South Prospect Street, Burlington, Vermont 05405 (802) 656-2127 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 2001 Ph.D. Sociology, University of Colorado at Boulder, with distinction 1989 B.A. Sociology, University of Vermont, Magna Cum Laude 1987 State University of New York at Catholic University, Lima, Peru ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2017 Fulbright Fellowship, Joint Centre for Disaster Research, Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand 2017- Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2008-2017 Associate Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2003-2008 Assistant Professor, University of Vermont, Department of Sociology 2001-2003 Assistant Professor, University of Akron, Department of Sociology 1994-1999 Research Assistant, Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado 1998 Adjunct Faculty, Regis University, Denver, Department of Sociology 1997-2000 Graduate Instructor, University of Colorado, Department of Sociology AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Sociology of Disaster, Children & Youth, Family, Gender, Qualitative Methods, Inequality, Service Learning BOOKS Alice Fothergill and Lori Peek. 2015. Children of Katrina. Austin: University of Texas Press. * *Winner of the Outstanding Scholarly Contribution (Book) Award, American Sociological Association Children and Youth Section, 2016 *Winner of the Betty and Alfred McClung Lee Book Award, Association for Humanist Sociology, 2016 *Honorable Mention, Leo Goodman Award for the American Sociological Association Methodology Section 2016. * Finalist, Colorado Book Awards, 2016 *Selected as Outstanding Academic Title by Choice magazine, Association of College and Research Libraries/American Library Association), 2017 Deborah S.K. Thomas, Brenda D. Phillips, William E. Lovekamp, Alice Fothergill, Editors. 2013. Social Vulnerability to Disasters: 2nd Edition. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis. -

In Recognition of Past and Present Service

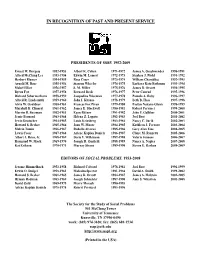

IN RECOGNITION OF PAST AND PRESENT SERVICE PRESIDENTS OF SSSP, 1952-2009 Ernest W. Burgess 1952-1953 Albert K. Cohen 1971-1972 James A. Geschwender 1990-1991 Alfred McClung Lee 1953-1954 Edwin M. Lemert 1972-1973 Stephen J. Pfohl 1991-1992 Herbert Blumer 1954-1955 Rose Coser 1973-1974 William Chambliss 1992-1993 Arnold M. Rose 1955-1956 Stanton Wheeler 1974-1975 Barbara Katz Rothman 1993-1994 Mabel Elliot 1956-1957 S. M. Miller 1975-1976 James D. Orcutt 1994-1995 Byron Fox 1957-1958 Bernard Beck 1976-1977 Peter Conrad 1995-1996 Richard Schermerhorn 1958-1959 Jacqueline Wiseman 1977-1978 Pamela A. Roby 1996-1997 Alfred R. Lindesmith 1959-1960 John I. Kitsuse 1978-1979 Beth B. Hess 1997-1998 Alvin W. Gouldner 1960-1961 Frances Fox Piven 1979-1980 Evelyn Nakano Glenn 1998-1999 Marshall B. Clinard 1961-1962 James E. Blackwell 1980-1981 Robert Perrucci 1999-2000 Marvin B. Sussman 1962-1963 Egon Bittner 1981-1982 John F. Galliher 2000-2001 Jessie Bernard 1963-1964 Helena Z. Lopata 1982-1983 Joel Best 2001-2002 Irwin Deutscher 1964-1965 Louis Kriesberg 1983-1984 Nancy C. Jurik 2002-2003 Howard S. Becker 1965-1966 Joan W. Moore 1984-1985 Kathleen J. Ferraro 2003-2004 Melvin Tumin 1966-1967 Rodolfo Alvarez 1985-1986 Gary Alan Fine 2004-2005 Lewis Coser 1967-1968 Arlene Kaplan Daniels 1986-1987 Claire M. Renzetti 2005-2006 Albert J. Reiss, Jr. 1968-1969 Doris Y. Wilkinson 1987-1988 Valerie Jenness 2006-2007 Raymond W. Mack 1969-1970 Joseph R. Gusfield 1988-1989 Nancy A. -

WILLIAM FOOTE WHYTE, <I>STREET CORNER SOCIETY</I

Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 50(1), 79–103 Winter 2014 View this article online at Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/jhbs.21630 C 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. WILLIAM FOOTE WHYTE, STREET CORNER SOCIETY AND SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OSCAR ANDERSSON Social scientists have mostly taken it for granted that William Foote Whyte’s sociological classic Street Corner Society (SCS, 1943) belongs to the Chicago school of sociology’s research tradition or that it is a relatively independent study which cannot be placed in any specific research tradition. Social science research has usually overlooked the fact that William Foote Whyte was educated in social anthropology at Harvard University, and was mainly influenced by Conrad M. Arensberg and W. Lloyd Warner. What I want to show, based on archival research, is that SCS cannot easily be said either to belong to the Chicago school’s urban sociology or to be an independent study in departmental and idea-historical terms. Instead, the work should be seen as part of A. R. Radcliffe-Brown’s and W. Lloyd Warner’s comparative research projects in social anthropology. C 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. INTRODUCTION Few ethnographic studies in American social science have been as highly praised as William Foote Whyte’s Street Corner Society (SCS) (1943c). The book has been re-published in four editions (1943c, 1955, 1981, 1993b) and over 200,000 copies have been sold (Adler, Adler, & Johnson, 1992; Gans, 1997). John van Maanen (2011 [1988]) compares SCS with Bronislaw Malinowski’s social anthropology classic Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1985 [1922]) and claims that “several generations of students in sociology have emulated Whyte’s work by adopting his intimate, live-in, reportorial fieldwork style in a variety of community settings” (p. -

SWS Network News – Fall 2014

I N S I D E Network news T H I S ISSUE: NETWORK NEWS OCTOBER 2014 Reports from 1 the Leadership As the new academic year gets under- Education”; “Gender and Sci- way, it’s time to mark your calendars ence”; “International Perspectives on Membership 5 for the upcoming Winter Meeting: Feminist Sociology”; “Global Femi- drive nist Partnerships”; “The Politics of Executive 7 FEMINISM IN THEORY, Paid Family Leave”; “Women and Office PRACTICE, AND POLICY Health”; and “Writing for Feminist Sociologists.” Session 9 February 19 - 22, 2015 summaries * Roundtables, poster sessions, new Washington, DC book exhibits, and mentoring sessions. Awards 11 Our meeting theme draws on SWS’s * A wide range of committee meet- G & S in the 20 historic mission to contribute to posi- ings, where the work of building the Classroom tive change for women, both in the organization, pursuing ongoing pro- academy and in society. We’ve chosen jects, and developing new initiatives Chapter 27 DC to highlight our goal of melding takes place Updates sociological insight with real-world ac- tivism and are now hard at work devel- * Lots of opportunities to see old Members 30 friends and make new ones at recep- Bookshelf oping the program. Here’s an early re- port on how things are shaping up: tions, coffee breaks, the banquet and auction, and other events for socializ- * A lineup of plenaries that includes ing, networking, and just hanging out. Global 33 “Building Feminist and Women’s Or- Feminist ganizations”; “The Gender Revolution: We’re enthusiastic about this lineup of Partnership Where are We Now?”; “Gender and panels, workshops, and activities. -

Sociology 861: Work and Occupations

SOCIOLOGY 861: WORK AND OCCUPATIONS Professor Arne Kalleberg Spring, 2016 Office: 261 Hamilton Hall (962-0630) Email: [email protected] Tuesday, 12:30-3:00 151 Hamilton Hall COURSE DESCRIPTION This course combines aspects of a survey course (an overview and synthesis of material on topics related to work and occupations in industrial societies) with those of a seminar (identification and intensive discussions of research questions). We will cover topics such as: concepts and theories of work and work organization; the relations between markets and work structures such as occupations, industries, classes, unions, and jobs; employment relations and labor market segmentation; professions and occupational control; occupational differentiation and inequality; gender differences in work and occupations; control over work activities and work time; individuals' assessments of their job satisfaction and quality of their jobs; social policies related to work; and the prospects for social movements related to work. We will place particular emphasis on comparative (historical, cross-national) perspectives on these issues. Each class will be framed around a set of questions that address particular topics, and that are related to the readings for that day. I will lead off in each class by providing an introduction and context to the day’s topic(s). In some of the classes, I will ask teams to stimulate debate and critical thinking about the questions for the day. I will then try to summarize the day’s discussion. READINGS Students are expected to participate in discussions of readings, so please complete them by the assigned date. These readings can be downloaded from the course’s “Sakai” website (sakai.unc.edu) or from the UNC Libraries e-journal collection. -

Toward a Humanistic Sociological Theory

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete.