T.F. Mcilwraith and the NUXALK (BELLA COOLA INDIANS)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia's Central Coast

A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast REPORT · 2021 citation Atlas, W. I., K. Connors, L. Honka, J. Moody, C. N. Service, V. Brown, M .Reid, J. Slade, K. McGivney, R. Nelson, S. Hutchings, L. Greba, I. Douglas, R. Chapple, C. Whitney, H. Hammer, C. Willis, and S. Davies. (2021). A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Pacific Salmon Foundation. authors Will Atlas, Katrina Connors, Jason Slade Rich Chapple, Charlotte Whitney Leah Honka Wuikinuxv Fisheries Program Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance Salmon Watersheds Program, Wuikinuxv Village, BC Campbell River, BC Pacific Salmon Foundation Vancouver, BC Kate McGivney Haakon Hammer, Chris Willis North Coast Stock Assessment, Snootli Hatchery, Jason Moody Fisheries and Oceans Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Nuxalk Fisheries Program Bella Coola, BC Bella Coola, BC Bella Coola, BC Stan Hutchings, Ralph Nelson Shaun Davies Vernon Brown, Larry Greba, Salmon Charter Patrol Services, North Coast Stock Assessment, Christina Service Fisheries and Oceans Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Kitasoo / Xai’xais Stewardship Authority BC Prince Rupert, BC Klemtu, BC Ian Douglas Mike Reid Salmonid Enhancement Program, Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Fisheries and Oceans Canada Management Department Bella Coola, BC Bella Bella, BC published by Pacific Salmon Foundation 300 – 1682 West 7th Avenue Vancouver, BC, V6J 4S6, Canada www.salmonwatersheds.ca A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast REPORT 2021 Acknowledgements We thank everyone who has been a part of this collaborative Front cover photograph effort to develop a salmon monitoring and stewardship and photograph on pages 4–5 framework for the Central Coast of British Columbia. -

Indigenous Peoples' Food Systems and Well-Being

Chapter 11 The Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program for Health revisited v nanCy J. turnEr 1 v WilFred r. talliO 2 v sanDy BurgEss 2, 3 v HarriEt V. KuHnlEin 3 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems & well-being 177 British Columbia Bella Coola Vancouver Canada Figure 11.1 NUXALK Nation Bella Coola, British Columbia Data from ESRI Global GIS, 2006. Walter Hitschfield Geographic Information Centre, McGill University Library. 1 school of Environmental studies, university of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada 4 2 Centre for indigenous nuxalk nation, peoples’ nutrition Indigenous Peoples, food systems, Bella Coola, and Environment (CinE) Key words > British Columbia, Canada and school of Dietetics traditional food, Nuxalk Nation, British Columbia, and Human nutrition, intervention 3 mcgill university, (retired) salmon arm, montreal, Quebec, British Columbia, Canada Canada Photographic section >> XXII 178 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems & well-being | Case studies | nuxalk “They came out in droves!” Rose Hans, in recollection of the feasts for youth that were part of the Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Program, as remembered in 2006 abstract Introduction the original diet of the nuxalk nation incorporated a range of nutritious fish and seafood, game and various plant foods, he Nuxalk Food and Nutrition including greens, berries and root vegetables. However, early Program was conceived in the research underlying the nuxalk Food and nutrition program demonstrated a dramatic shift in diet during the twentieth early 1980s and began officially in century, with less use of traditional food and greater reliance 1983. It was a collaborative research on processed and less healthy food, combined with a more project involving the Nuxalk1 Nation sedentary lifestyle. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

Introductions & Greetings 2018-20

Rosser’s Indigenous Language Club Introductions & Greetings 2018-20 Rosser’s Indigenous Language Club Introductions & Greetings This book is dedicated to the students, staff & community of Rosser Elementary School. Researched & Designed by Brandi Price & Brentwood Park Indigenous Students. Photo Credits: Brandi Price Picture Credits: Pixabay.com Audio Recording: Brentwood Park Indigenous students Edited by Burnaby Indigenous Resource Team 2018-2020 Table of Contents 1. What is Indigenous Language Club Page 2 2. Acknowledgements Page 2 3. Kwak’wala Page 3 4. Nuxalk Page 3 5. Nēhiyawēwin-Y Dialect Page 4-5 6. Secwepemctsín Page 6 7. Secwepemctsín Page 7 8. Español Page 7 9. Secwepemctsín Page 8 10. Kwak’wala Page 9 11. Indigenous Language Map of Canada Page 10 12. Map of the World Page 11 13. UNESCO status of Indigenous Languages in Canada Page 12-13 14. Resources Page 14 About Indigenous Language Club Rosser language club is a safe place for students to increase their awareness of the Indigenous languages in Canada and is inclusive to all languages. All Indigenous languages in Canada are at a high risk of becoming endangered or extinct due to the impacts of colonization and residential schools. Indigenous communities are currently engaged in a variety of efforts to maintain and revitalize their languages. Using the Truth And Reconciliation (TRC), section 13 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples (UNDRIP), article 13 as a guide, I wanted to create an opportunity for urban indigenous students who come from various cultural backgrounds to explore, learn, research and play with their ancestral language through firstvoices.com, learnmichif.com, youtube and other online platforms. -

Attribution, Continuity, and Symbolic Capital in a Nuxalk Community

THUNDER AND BEING: ATTRIBUTION, CONTINUITY, AND SYMBOLIC CAPITAL IN A NUXALK COMMUNITY by CHRISTOPHER WESLEY SMITH B.A., University of Alaska Anchorage, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2019 © Christopher Wesley Smith, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis entitled: Thunder and Being: Attribution, Continuity, and Symbolic Capital in a Nuxalk Community submitted by Christopher Wesley Smith in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology Examining Committee: Jennifer Kramer Supervisor Bruce Granville Miller Supervisory Committee Member Additional Examiner ii Abstract This ethnography investigates how Nuxalk carpenters (artists) and cultural specialists discursively connect themselves to cultural treasures and historic makers through attributions and staked cultural knowledge. A recent wave of information in the form of digital images of ancestral objects, long-absent from the community, has enabled Nuxalk members to develop connoisseurial skills to reinterpret, reengage, and re-indigenize those objects while constructing cultural continuity and mobilizing symbolic capital in their community, the art market, and between each other. The methodologies described in this ethnography and deployed by Nuxalk people draw from both traditional knowledge and formal analysis, problematizing the presumed binary division between these epistemologies in First Nations art scholarship and texts. By developing competencies with objects though exposure and familiarity, Nuxalk carpenters and cultural specialists are driving a spiritual and artistic resurgence within their community. -

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools

Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory Curriculum and Resources for First Nations Language Programs in BC First Nations Schools Resource Directory: Table of Contents and Section Descriptions 1. Linguistic Resources Academic linguistics articles, reference materials, and online language resources for each BC First Nations language. 2. Language-Specific Resources Practical teaching resources and curriculum identified for each BC First Nations language. 3. Adaptable Resources General curriculum and teaching resources which can be adapted for teaching BC First Nations languages: books, curriculum documents, online and multimedia resources. Includes copies of many documents in PDF format. 4. Language Revitalization Resources This section includes general resources on language revitalization, as well as resources on awakening languages, teaching methods for language revitalization, materials and activities for language teaching, assessing the state of a language, envisioning and planning a language program, teacher training, curriculum design, language acquisition, and the role of technology in language revitalization. 5. Language Teaching Journals A list of journals relevant to teachers of BC First Nations languages. 6. Further Education This section highlights opportunities for further education, training, certification, and professional development. It includes a list of conferences and workshops relevant to BC First Nations language teachers, and a spreadsheet of post‐ secondary programs relevant to Aboriginal Education and Teacher Training - in BC, across Canada, in the USA, and around the world. 7. Funding This section includes a list of funding sources for Indigenous language revitalization programs, as well as a list of scholarships and bursaries available for Aboriginal students and students in the field of Education, in BC, across Canada, and at specific institutions. -

7"'" Eyak Tlingit/1\ Dialects

301 302 THE ATHABASCAN COMPONENT OF NUXALK so be shown that the Nuxalk-Athabascan connection underlies certain phonological traits and developments in Nuxalk that are quite unique in Salish. Considering Hank Nater Red Earth Creek, Alberta the typological distance between Salish and Athabascan in general, we infer that Athabascan linguistic pressure has been more penetrating in Nuxalk than in other Canada TOGlXO Salish;2 the likelihood that the origin of the Nuxalk-Athabascan interrelation antedates the development of the Nuxalk-Wakash Sprachbund is an indication that O. Introduction. Obvious lexical similarities between Nuxalk (Bella Coola, at least a section of the Nuxalk population has ancestral ties with the Interior Salish) and Upper North Wakash have been described on previous occasions (Nater Salish (which is corroborated by the fact that the Salish portion of the Nuxalk 1974, 1977, 1984; Nater and Rath 1987; Newman 1973). I also reported that a few lexicon links Nuxalk with both Coast and Interior Salish, cf. Nater 1984: XVII). Nuxalk words appear to be of Athabascan origin, and it is the latter portion of In this paper, the circumflex (as in lei le'l I§/) is used instead of the hachek the Nuxalk lexicon that we shall examine here in more detail than before. Note to transcribe apico-alveolars; in Iii and Iii, the superscript dot replaces the that, while I had presumed that traces of Athabascan vocabulary in Nuxalk were subscript dot, and Igl = IG/. References are abbreviated as follows: C = Cook largely attributable to interaction with speakers of contemporary neighboring 1983; CD = Carrier Dictionary Committee 1974; K70 = Kuipers 1970, K74 = Kuipers Athabascan languages (Carrier, Chilcotin), further research has revealed that 1974, K82 = Kuipers 1982, K89 = Kuipers 1989; KL = Krauss and Leer 1981; L = most such borrowings are older than hitherto alleged; in addition, the number of Leer 1979; LR = Lincoln and Rath 1986; MI = Morice 1932 (vol. -

Medical Missions and Indigenous Medico-Spiritual Cosmologies on the Central Coast of British Columbia, 1897-1914

A Time to Heal: Medical Missions and Indigenous Medico-Spiritual Cosmologies on the Central Coast of British Columbia, 1897-1914 by Alice Chi Huang B.A., University of British Columbia, 2012 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Ó Alice Chi Huang 2017 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2017 Approval Name: Alice Chi Huang Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title: A Time to Heal: Medical Missions and Indigenous Medico-Spiritual Cosmologies on the Central Coast of British Columbia, 1897-1914 Examining Committee: Chair: Thomas Kuehn Associate Professor Mary-Ellen Kelm Senior Supervisor Professor Luke Clossey Supervisor Associate Professor Paige Raibmon External Examiner Associate Professor Department of History University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: July 14, 2017 ii Abstract In the late 1890s, the Methodist Church of Canada established medical missions among the two largest Indigenous settlements of the Central Coast: the Heiltsuk village of Bella Bella, and the Nuxalk village of Bella Coola. These medical missions emphasized the provision of biomedical care as an evangelization strategy, since the Methodists believed that God’s grace and power manifested through their integrated medico-spiritual work. Although missionaries attempted to impose Euro-Canadian notions of health and healing, their assimilatory efforts resulted in an unexpected outcome. Rather than abandoning Indigenous healing, the Heiltsuk and Nuxalkmc recognized the limitations of biomedicine but also its advantages, and thus incorporated biomedical care into their cultural beliefs and practices. This thesis examines the convergence of Euro-Canadian and Indigenous healing systems and how it resulted in the emergence of medical pluralism, and considers how this reciprocal process of exchange affected both missionaries and Indigenous peoples. -

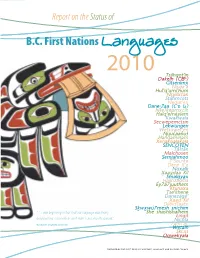

2010 Report on the Status of B.C First Nations Languages

Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages 2010 Tsilhqot’in Dakelh (ᑕᗸᒡ) Gitsenimx̱ Nisg̱a’a Hul’q’umi’num Nsyilxcən St̓át̓imcets Nedut’en Dane-Zaa (ᑕᓀ ᖚ) Nłeʔkepmxcín Halq’eméylem Kwak̓wala Secwepemctsin Lekwungen Wetsuwet’en Nuučaan̓uɫ Hən̓q̓əm̓inəm̓ enaksialak̓ala SENĆOŦEN Tāłtān Malchosen Semiahmoo T’Sou-ke Dene K’e Nuxalk X̱aaydaa Kil Sm̓algya̱x Hailhzaqvla Éy7á7juuthem Ktunaxa Tse’khene Danezāgé’ X̱aad Kil Diitiidʔaatx̣ Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim “…I was beginning to fear that our language was slowly She shashishalhem Łingít disappearing, especially as each Elder is put into the ground.” Nicola Clara Camille, secwepemctsin speaker Pəntl’áč Wetalh Ski:xs Oowekyala prepared by the First peoples’ heritage, language and Culture CounCil The First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council (First We sincerely thank the B.C. First Nations language revitalization Peoples’ Council) is a provincial Crown Corporation dedicated to First experts for the expertise and input they provided. Nations languages, arts and culture. Since its formation in 1990, the Dr. Lorna Williams First Peoples’ Council has distributed over $21.5 million to communi- Mandy Na’zinek Jimmie, M.A. ties to fund arts, language and culture projects. Maxine Baptiste, M.A. Dr. Ewa Czaykowski-Higgins The Board and Advisory Committee of the First Peoples’ Council consist of First Nations community representatives from across B.C. We are grateful to the three language communities featured in our case studies that provided us with information on the exceptional The First Peoples’ Council Mandate, as laid out in the First Peoples’ language revitalization work they are doing. Council Act, is to: Nuučaan̓uɫ (Barclay Dialect) • Preserve, restore and enhance First Nations’ heritage, language Halq’emeylem (Upriver Halkomelem) and culture. -

Table of Contents Monica Auer, Forum for Research and Policy in Communications (FRPC)

Abstracts & Bios, Page 1 PRESENTER BIOGRAPHIES AND PRESENTATION ABSTRACTS Table of Contents Monica Auer, Forum for Research and Policy in Communications (FRPC)...................................................2 Melissa Begay, Native Public Media............................................................................................................2 Geneviève Bonin, University of Ottawa.......................................................................................................3 Andrew Cardozo, Pearson Centre................................................................................................................4 Les Carpenter, Native Communications Society (NCS) of the NWT.............................................................4 Penny Carpenter, First Mile Connectivity Consortium.................................................................................5 Annie Clair, Pjilasi Mi'kma'ki........................................................................................................................5 Kristiana Clemens, Community Media Advocacy Centre.............................................................................6 Sam Cohn-Cousineau, Isuma Distribution International..............................................................................7 Conner Coles, Native Communications Society (NCS) of the NWT..............................................................8 Aliaa Dakroury, Saint Paul University...........................................................................................................8 -

Broadcasting Live from Unceded Coast Salish Territory: Aboriginal Community Radio, Unsettling Vancouver

Broadcasting Live from Unceded Coast Salish Territory: Aboriginal Community Radio, Unsettling Vancouver Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Margaret Helen Bissler, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Christine Ballengee-Morris Danielle Fosler-Lussier Copyright by Margaret Helen Bissler 2014 Abstract This thesis examines moments of spatial, historical, and identity transformation through the performance of aboriginal community radio production in contemporary Vancouver, BC. It highlights points at which space is marked as indigenous and colonial through physical movement and through discourse. Beginning with a trip to record a public demonstration for later broadcast, this thesis follows the event in a public performance to question and unpack spatial, sonic, and historical references made by participants. The protest calls for present action while drawing upon past experiences of indigenous peoples locally and nationwide that affect the lived present and foreseeable future. This thesis also moves to position aboriginal community radio practice in a particular place and time, locating the discussion in unceded indigenous territory within the governmental forces of Canadian regulation at a single radio station. Vancouver Co- op Radio, to provide a more coherent microcosm of Vancouver's indigenous community radio scene. CFRO is located in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and its shows, mostly aired live from the studio, broadcast a marginalized voices. The content of its overtly indigenous shows includes aboriginal language learning and revival, aboriginal political issues or “talk radio,” “NDN” (pronounced “Indian”) pop culture/music, and aboriginal music more broadly writ. -

DEAN River BC Alert

Disaster on the Dean In what appears to be a repeat of the 2013 massacre of wild steelhead and other wild salmon in the Dean Channel in Central British Columbia by a surplus of commercial seine and net fishers seeking out hatchery salmon returning amidst wild steelhead and wild chum salmon to the Dean and Kitimat Rivers, Canadian conservationists and anglers can only point to unanswered questions about the intensity of the fleet and the catch and bycatch as the diminishing wild steelhead in the Dean began showing the carnage of net marks as they ascended in their home waters. Apparently the commercial opening was unannounced to the lodges and tourism engine of Central BC. According to local conservationists, the commercial fleet is completely unmonitored. The Dean Channel, where portion of the Area 8 commercial fishery occurs, typically sees minimal to moderate commercial fishing pressure, but the recent Skeena closure was very detrimental to the Dean steelhead as Skeena boats harvested low value Chum in area 8. This fisheries management blunder from 2013 is repeating itself in 2017. Anglers and guide operations were taken by surprise in 2013 and merely resulted in some angry letters being sent to the Fisheries Minister (Gail Shae) and Bella Coola DFO Area Manager Dan Wagner. Unfortunately, all after the damage was done. The bottom line is that the chum fishery should not be taking place because of the impact on Dean steelhead runs, but also because chum stocks in both the Dean and Bella Coola rivers have declined 80 per cent in recent years.