A Look at the Interdependence of the Triangle ‚Casinos – Land Claims – Identity’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delaware Indian Land Claims: a Historical and Legal Perspective

Delaware Indian land Claims: A Historical and Legal Perspective DAVID A. EZZO Alden, New York and MICHAEL MOSKOWITZ Wantagh, New York In this paper we shall discuss Delaware Indian land claims in both a histori cal and legal context. The first section of the paper deals with the historical background necessary to understand the land claims filed by the Delaware. In the second part of the paper the focus is on a legal review of the Delaware land claims cases. Ezzo is responsible for the first section while Moskowitz is responsible for the second section. 1. History The term Delaware has been used to describe the descendants of the Native Americans that resided in the Delaware River Valley and other adjacent areas at the start of the 17th century. The Delaware spoke two dialects: Munsee and Unami, both of these belong to the Eastern Algonquian Lan guage family. Goddard has noted that the Delaware never formed a single political unit. He also has noted that the term Delaware was only applied to these groups after they had migrated from their original Northeastern homeland. Goddard sums up the Delaware migration as follows: The piecemeal western migration, in the face of white settlement and its attendant pressures during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, left the Delaware in a number of widely scattered places in Southern Ontario, Western New York, Wisconsin, Kansas and Oklahoma. Their history involves the repeated divisions and consolidations of many villages and of local, political and linguistic groups that developed in complicated and incompletely known ways. In addition, individuals, families and small groups were constantly moving from place to place. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Oneida Nation Cultural Symbols in and Around Oneida Reservation

Oneida Cultural Heritage Department By: Judith L. Jourdan, Genealogist, Cultural Heritage Department Edit, Revision, and Layout: Tiffany Schultz (09/13) Oneida Nation Cultural Symbols: In and Around the Oneida Reservation Drawing by: Judith L. Jourdan © INTRODUCTION The use of symbolism within the THE IROQUOIS CREATION STORY Iroquois culture dates back to the time of Creation. Among the Iroquois, the power of their Every group of people has its own story symbolism is profound because they used the of creation, an explanation of how the earth and symbols as a means to feed their minds and to human beings came to exist. The guide their actions. Like the stars and stripes and Haudenosaunee people, later renamed the the symbols on the back of a dollar bill to Iroquois by early French explorers, are no Americans, so are there many sites in and different. Being a nation of oral tradition, the around the Oneida Reservation that depict following story and variations of it have been symbols of Oneida. passed down from generation to generation. Today Iroquois people can be found all over the eastern, northeastern and the Midwestern United States. Many of them continue the ancient ways, The sea animals plunged down into the preserving the language and ceremonies. water looking for some earth. Muskrat succeeded and came up with a large handful of The creation story, as well as other earth, which he placed in Turtle’s back and the stories about Haudensaunee life, is still told to earth began to grow. Thus we call Mother the children. From this story can be derived Earth, “Turtle Island”. -

Official Guide to Native American Communities in Wisconsin

Official Guide to Native American Communities in Wisconsin www.NativeWisconsin.com Shekoli (Hello), elcome to Native Wisconsin! We are pleased to once again provide you with our much anticipated NATIVE WISCONSIN MAGAZINE! WAs always, you will find key information regarding the 11 sovereign tribes in the great State of Wisconsin. From history and culture to current events and new amenities, Native Wisconsin is the unique experience visitors are always looking for. As our tribal communities across WI continue to expand and improve, we want to keep you informed on what’s going on and what’s in store for the future. With a new vision in place, we plan to assist each and every beautiful reservation to both improve what is there, and to create new ideas to work toward. Beyond their current amenities, which continue to expand, we must diversify tribal tourism and provide new things to see, smell, touch, taste, and hear. Festivals, culinary arts, song and dance, storytelling, Lacrosse, new tribal visitor centers, even a true hands on Native Wisconsin experience! These are just a few of the elements we want to provide to not only give current visitors what they’ve been waiting for, but to entice new visitors to come see us. We are always looking to our visitors for input, so please let us know how you would like to experience NATIVE WISCONSIN in the future, and we will make it happen for you. We are looking forward to 2015 and beyond. With the return of this magazine, a new website, our annual conference in Mole Lake, and a new online TV show in development, things are getting exciting for all of us. -

Topography Section References

Section 8 References 8. REFERENCES 1. Purpose and Need for the proposed Action Bureau of Indian Affairs (2006). Website. Retrieved May 24, 2006 from http://www.doi.gov/bureau-indian-affairs.html. 3.2.1 Topography Fenneman, N.M., & Johnson, D.W. (1946). Physical Divisions of the United States: Washington, DC. US Geological Survey Special Map Series. NASA Visible Earth Image catalog (1991, October 18). SRTM, Landsat. Retreived February 13, 2000, from http://visibleearth.nasa.gov USGS (2006). Seamless Data Distribution System. Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved March 22, 2006, from http://seamless.usgs.gov 3.2.2 Soils USDA– SCS (1987). Hydric Soils of the United States. United States Department of Agriculture– Soil Conservation Service. USDA. Natural Resource Conservation Service Soil Data Mart. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from http://soildatamart.nrcs.usda.gov/. United States Department of Agriculture. Natural Resources Conservation Service. (1993, October). Soil Survey Manual. Retrieved April 8, 2006 from http://soils.usda.gov/technical/manual/print_version/chapter6.html U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, (2005). National Soil Survey Handbook, title 430-VI. Retrieved from http://soils.usda.gov/technical/handbook/ 3.2.3 Geological Setting and Mineral Resources Cadwell, D.H., Connally, G.G., Dineen, R.J., Fleisher, P.J., & Rich, J.L. (1987) Surficial Geologic Map of New York – Hudson-Mohawk Sheet. New York State Museum Geological Survey. Bureau of Indian Affairs Draft EIS 8-1 Oneida Nation of New York Conveyance of Lands Into Trust Section 8 References Fisher, D.W., Isachsen, Y.W., & Rickard, L.V. -

Annual Report of New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs, 1973-74

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 103 184 RC 008 414 AUTHOR Hathorn, John R. TITLE Annual Report of New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs, 1973-74. INSTITUTION New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs, Albany. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 35p.; For related documents, see ED 032 959; ED 066 279-280; ED 080 267 EDRS PRICE NF-$0.76 HC-$1.95 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTJRS *American Indians; *Innual Reports; Clinics; Committees; Educational Finance; Expenditures; Health Services; Leadership; Legislation; *Reservations (Indian); *Services; Social Services; *State Programs; Transportation IDENTIFIERS *New York ABSTPACT The purpose and function of the New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs is to render, through the several state departments and agencies represented, various services to the 8 American Indian reservations (Cattaraugus, St. Regis, Tonawanda, Tuscarora, Allegany, Onandaga, Shinpecock, and Poospatuck) located within the boundaries of New York. This 1973-74 annual report describes the various services rendered by the State Departments of Commerce, Education, Health, Transportation, and Social Services. Information is given on educational programs, clinic services, general nursing services, dental services, transportation, social services, housing, and foster care. The 1973 post-session and the 1974 legislative session activities of the State Assembly Subcommittee on Indian Affairs, which serves as advocate for the Indian people, are briefly discussed. Addresses of the Interdepartmental Committee members and of the Indian Reservation leaders and officials are included. (NQ) a BEST COPY AVAILABLE r ANNUAL REPORT \ Ui of NEW YORK STATE INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEE on INDIAN AFFAIRS 19731974 us otomermaNY OF WEALTH InluontoPi aWEIS AO* NATIONAL INSTITUTEor EDUCATION DOCUMENT HAS BEEN IIrrRO O's.,CEO fxAtit,v AS REtt IvEo 1;oM 1HE PERSON OR ORGANIZA T1ON OalcoN A +NG IT POINTS Or VIEW OR °Pt N IONS STATED DO NOT NtcEssmaiLv REPRE SENT erg ictm. -

Curing the Tribal Disenrollment Epidemic: in Search of a Remedy

CURING THE TRIBAL DISENROLLMENT EPIDEMIC: IN SEARCH OF A REMEDY Gabriel S. Galanda and Ryan D. Dreveskracht* This Article provides a comprehensive analysis of tribal membership, and the divestment thereof—commonly known as “disenrollment.” Chiefly caused by the proliferation of Indian gaming revenue distributions to tribal members over the last 25 years, the rate of tribal disenrollment has spiked to epidemic proportions. There is not an adequate remedy to stem the crisis or redress related Indian civil rights violations. This Article attempts to fill that gap. In Part I, we detail the origins of tribal membership, concluding that the present practice of disenrollment is, for the most part, a relic of the federal government’s Indian assimilation and termination policies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In Part II, we use empirical disenrollment case studies over the last 100 years to show those federal policies at work during that span, and thus how disenrollment operates in ways that are antithetical to tribal sovereignty and self-determination. Those case studies highlight the close correlation between federally prescribed distributions of tribal governmental assets and monies to tribal members on a per-capita basis, and tribal governmental mass disenrollment of tribal members. In Part III, we set forth various proposed solutions to curing the tribal disenrollment epidemic, in hope of spurring discussion and policymaking about potential remedies at the various levels of federal and tribal government. Our goal is to find a cure, before it is too late. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 385 A. Overview .................................................................................................... 385 B. Background ................................................................................................ 389 I. ORIGINS OF TRIBAL “MEMBERSHIP” ................................................................ -

Oriskany:Aplace of Great Sadness Amohawk Valley Battelfield Ethnography

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Ethnography Program Northeast Region ORISKANY:APLACE OF GREAT SADNESS AMOHAWK VALLEY BATTELFIELD ETHNOGRAPHY FORT STANWIX NATIONAL MONUMENT SPECIAL ETHNOGRAPHIC REPORT ORISKANY: A PLACE OF GREAT SADNESS A Mohawk Valley Battlefield Ethnography by Joy Bilharz, Ph.D. With assistance from Trish Rae Fort Stanwix National Monument Special Ethnographic Report Northeast Region Ethnography Program National Park Service Boston, MA February 2009 The title of this report was provided by a Mohawk elder during an interview conducted for this project. It is used because it so eloquently summarizes the feelings of all the Indians consulted. Cover Photo: View of Oriskany Battlefield with the 1884 monument to the rebels and their allies. 1996. Photograph by Joy Bilharz. ExEcuTivE SuMMARy The Mohawk Valley Battlefield Ethnography Project was designed to document the relationships between contemporary Indian peoples and the events that occurred in central New York during the mid to late eighteenth century. The particular focus was Fort Stanwix, located near the Oneida Carry, which linked the Mohawk and St. Lawrence Rivers via Wood Creek, and the Oriskany Battlefield. Because of its strategic location, Fort Stanwix was the site of several critical treaties between the British and the Iroquois and, following the American Revolution, between the latter and the United States. This region was the homeland of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy whose neutrality or military support was desired by both the British and the rebels during the Revolution. The Battle of Oriskany, 6 August 1777, occurred as the Tryon County militia, aided by Oneida warriors, was marching to relieve the British siege of Ft. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______DONALD L

No. 07-526 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _________ DONALD L. CARCIERI, GOVERNOR OF RHODE ISLAND, ET AL., Petitioners, v. DIRK KEMPTHORNE, SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR, ET AL., Respondents. ________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit ________ BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL CONGRESS OF AMERICAN INDIANS AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENTS ________ JOHN DOSSETT IAN HEATH GERSHENGORN NATIONAL CONGRESS OF Counsel of Record AMERICAN INDIANS SAM HIRSCH 1301 Connecticut Ave., N.W. JENNER & BLOCK LLP Washington, DC 20005 1099 New York Ave., N.W. (202) 466-7767 Washington, DC 20001 (202) 639-6000 RIYAZ A. KANJI PHILIP P. FRICKEY KANJI & KATZEN, PLLC UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, 101 North Main Street BERKELEY Suite 555 SCHOOL OF LAW Ann Arbor, MI 48104 892 Simon Hall (734) 769-5400 Berkeley, CA 94720 (510) 643-4180 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE.............................1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..........................................................2 ARGUMENT ...............................................................6 I. THE INDIAN LAND CONSOLIDATION ACT GIVES THE SECRETARY AUTHORITY UNDER SECTION 465 TO TAKE LAND IN TRUST FOR THE NARRAGANSETT INDIAN TRIBE.....................................................................6 II. THE SECRETARY HAS STATUTORY AUTHORITY UNDER THE IRA TO TAKE LAND IN TRUST FOR THE NARRAGANSETT INDIAN TRIBE......................9 A. The IRA Leaves Ample Room for the Secretary’s Reasonable Interpretation. ........11 1. The Definition of “Indian” Is Not Exhaustive.................................................12 2. Congress Did Not Unambiguously Require “Now” to Mean “At the Time of Enactment.”...............................................14 3. Section 465 Provides the Secretary with Broad Authority to Take Land in Trust for an “Indian Tribe.” ................................21 ii B. -

Table-12.Pdf

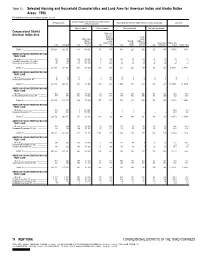

Table 12. Selected Housing and Household Characteristics and Land Area for American Indian and Alaska Native Areas: 1990 [For definitions of terms and meanings of symbols, see text] Occupied housing units with American Indian, Eskimo, All housing units or Aleut householder Households with American Indian, Eskimo, or Aleut householder Land area Owner occupied Renter occupied Family households Nonfamily households Congressional District Mean con- American Indian Area tract rent (dollars), Female Mean value specified house- (dollars), renter Married- holder, no specified paying cash couple husband Householder Square kilo- Total Occupied Total owner Total rent Total family present Total living alone meters Square miles ------------------------ District 1 239 124 192 807 313 139 800 176 637 364 224 109 125 105 1 650.6 637.3 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 219 180 139 95 800 13 400 108 72 24 44 44 3.6 1.4 Poospatuck Reservation, NY (state)-------- 46 45 29 175 200 2 313 23 13 6 8 8 .2 .1 Shinnecock Reservation, NY (state)-------- 173 135 110 86 100 11 458 85 59 18 36 36 3.4 1.3 ----------------------- District 23 243 283 211 591 264 63 700 234 286 331 228 77 167 128 15 504.1 5 986.1 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 20 1211–1363104421.2.1 Oneida (East) Reservation, NY------------ 20 1211–1363104421.2.1 ----------------------- District 24 261 036 202 380 934 46 900 489 264 1 055 734 234 368 291 32 097.8 12 393.0 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 754 634 561 45 000 64 184 485 342 106 140 124 49.2 19.0 St. -

235-1 Cherokee Freedmen Brief

Case 1:13-cv-01313-TFH Document 235-1 Filed 01/31/14 Page 1 of 57 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) THE CHEROKEE NATION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) RAYMOND NASH, et al., ) ) Defendants /Cross-Claimants/ ) Counter-Claimants ) ) -and- ) ) MARILYN VANN, et al. ) Case No. 1:13-cv-01313 (TFH) ) Judge: Thomas F. Hogan Intervenors/Defendants/Cross- ) Claimants/Counter-Claimants ) ) v. ) ) THE CHEROKEE NATION, et al., ) ) Counter-Defendants, ) ) -and- ) ) SALLY JEWELL, SECRETARY OF THE ) INTERIOR, AND THE UNITED STATES ) DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, ) ) Counter-Claimants/Cross-Defendants. ) THE CHEROKEE FREEDMEN’S MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN OPPOSITION TO THE CHEROKEE PARTIES’ MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND IN SUPPORT OF THE CHEROKEE FREEDMEN’S CROSS-MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT Case 1:13-cv-01313-TFH Document 235-1 Filed 01/31/14 Page 2 of 57 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. OVERVIEW AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND ........................................................... 1 II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................................... 4 A. Statement of Undisputed Facts Material to Partial Summary Judgment ............................ 4 B. Historical Background of the Treaty and its Interpretation ................................................ 6 1. Slavery in the Cherokee Nation Prior to the Civil War ................................................ 6 2. The Cherokee Nation Sides with the Confederacy. ...................................................