The Indian Law, Although a Part of the Scheme of General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Effects of PCB Contamination on the Environment and the Cultural Integrity of the St

University of Vermont UVM ScholarWorks Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2015 Effects of PCB Contamination on the Environment and the Cultural Integrity of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe in the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne Kim Ellen McRae University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons Recommended Citation McRae, Kim Ellen, "Effects of PCB Contamination on the Environment and the Cultural Integrity of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe in the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne" (2015). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 522. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/522 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at UVM ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of UVM ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTS OF PCB CONTAMINATION ON THE ENVIRONMENT AND THE CULTURAL INTEGRITY OF THE ST. REGIS MOHAWK TRIBE IN THE MOHAWK NATION OF AKWESASNE A Dissertation Presented by Kim McRae to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Specializing in Natural Resources May, 2015 Defense Date: May, 2015 Thesis Committee: Saleem Ali, Ph.D., Advisor Cecilia Danks, Ph.D., Co-Advisor Susan Comerford, Ph.D., Chair Glenn McRae, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of Graduate College ABSTRACT The following research project examines the effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on the environment and the cultural integrity of the St. -

Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Environment Division Environmental Assessment Form Project Name: St. Regis River Water Main Crossing P

Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Environment Division Environmental Assessment Form Project Name: St. Regis River Water Main Crossing Project Developer: Colleen Thomas, Director, Planning & Infrastructure Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Project Coordinator: Rob Henhawk, Field Superintendant Brent Herne, Construction Manager Address: 2817 State Route 95 Akwesasne NY 13655 Phone Number: 1-518-358-4205 FAX Number: 1-518-358-5919 Other Contacts: Shawn Martin Manager, Public Works Aaron Jarvis, Tisdel Associates, Project Engineer 1 © Copyright 2007 St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, or its Licensors. All rights reserved. Introduction It is the tradition of the Mohawk People to look seven generations ahead in making decisions that affect the community. It is in this spirit that the Environmental Review Process has been developed. The resources available on the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation are limited and dwindling with each year that passes. It is the intention of this process to increase awareness of available resources and ensure that all consideration of these resources is taken when initiating a project. Focus and vigilance are required to make sure the seventh generation will have all that is necessary to maintain and continue our way of life. This community is unique and consists of cultural resources that have survived countless efforts to eliminate them and they are deserving of our protection and care. Development can proceed and remain in harmony with the cultural values passed on to us by our ancestors, but it requires forethought and effort. The land and resources should be considered as a gift to pass down to future generations, and as such it should remain as whole, intact, and healthy as it was received so that it may sustain them. -

Annual Report of New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs, 1973-74

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 103 184 RC 008 414 AUTHOR Hathorn, John R. TITLE Annual Report of New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs, 1973-74. INSTITUTION New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs, Albany. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 35p.; For related documents, see ED 032 959; ED 066 279-280; ED 080 267 EDRS PRICE NF-$0.76 HC-$1.95 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTJRS *American Indians; *Innual Reports; Clinics; Committees; Educational Finance; Expenditures; Health Services; Leadership; Legislation; *Reservations (Indian); *Services; Social Services; *State Programs; Transportation IDENTIFIERS *New York ABSTPACT The purpose and function of the New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs is to render, through the several state departments and agencies represented, various services to the 8 American Indian reservations (Cattaraugus, St. Regis, Tonawanda, Tuscarora, Allegany, Onandaga, Shinpecock, and Poospatuck) located within the boundaries of New York. This 1973-74 annual report describes the various services rendered by the State Departments of Commerce, Education, Health, Transportation, and Social Services. Information is given on educational programs, clinic services, general nursing services, dental services, transportation, social services, housing, and foster care. The 1973 post-session and the 1974 legislative session activities of the State Assembly Subcommittee on Indian Affairs, which serves as advocate for the Indian people, are briefly discussed. Addresses of the Interdepartmental Committee members and of the Indian Reservation leaders and officials are included. (NQ) a BEST COPY AVAILABLE r ANNUAL REPORT \ Ui of NEW YORK STATE INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEE on INDIAN AFFAIRS 19731974 us otomermaNY OF WEALTH InluontoPi aWEIS AO* NATIONAL INSTITUTEor EDUCATION DOCUMENT HAS BEEN IIrrRO O's.,CEO fxAtit,v AS REtt IvEo 1;oM 1HE PERSON OR ORGANIZA T1ON OalcoN A +NG IT POINTS Or VIEW OR °Pt N IONS STATED DO NOT NtcEssmaiLv REPRE SENT erg ictm. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

6 MB Searchable

This document is from the Cornell University Library's Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections located in the Carl A. Kroch Library. If you have questions regarding this document or the information it contains, contact us at the phone number or e-mail listed below. Our website also contains research information and answers to frequently asked questions. http://rmc.library.cornell.edu Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections 2B Carl A. Kroch Library Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 Phone: (607) 255-3530 Fax: (607) 255-9524 E-mail: [email protected] CALENDAR 1934-1944 1934 J anuar'7 8 Tonawanda Reservation, New York Jesse Cornplanter to Joseph Keppler I IROQUOIS S~ing that he used the money sent tor PAPERS food instead ot overalls because he could JOSEPH KEPPLER not get on C. W. A. work because he is COLLE.CTION disabled with a pension pending; rpporting he can get no help trom the various veteran agencies supposed to make it available and that his mind 1s so upset he cannot work on his tather's notes and records. J anu8r7 27 Akron, Bew York Dinah Sundown to Joseph Keppler IROQUOIS PAPERS Reporting accident ot previous June and JOSEPH KEPPLER s81ing she vas on crutches tor 5 months; COLLECTION aSking tor clothes; announcing that New Year's dances are Just over. [Marked: Answered, in Keppler's hand) Ji'ebru8l'7 1 Lawtons, Bew York Fred Ninham to Joseph Keppler IROQUOIS S~ing he has made inquir'7 about a pig- PAPERS head mask but has located none as yet; JOSEPH KEPPLER reporting that the New Y ear Ce.remo~ COLLECTION was well attended and that Arthur Parker was a recent visitor at the Reservation r:r>.:., tJ. -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ............................................................... -

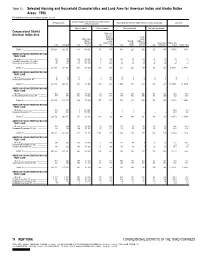

Table-12.Pdf

Table 12. Selected Housing and Household Characteristics and Land Area for American Indian and Alaska Native Areas: 1990 [For definitions of terms and meanings of symbols, see text] Occupied housing units with American Indian, Eskimo, All housing units or Aleut householder Households with American Indian, Eskimo, or Aleut householder Land area Owner occupied Renter occupied Family households Nonfamily households Congressional District Mean con- American Indian Area tract rent (dollars), Female Mean value specified house- (dollars), renter Married- holder, no specified paying cash couple husband Householder Square kilo- Total Occupied Total owner Total rent Total family present Total living alone meters Square miles ------------------------ District 1 239 124 192 807 313 139 800 176 637 364 224 109 125 105 1 650.6 637.3 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 219 180 139 95 800 13 400 108 72 24 44 44 3.6 1.4 Poospatuck Reservation, NY (state)-------- 46 45 29 175 200 2 313 23 13 6 8 8 .2 .1 Shinnecock Reservation, NY (state)-------- 173 135 110 86 100 11 458 85 59 18 36 36 3.4 1.3 ----------------------- District 23 243 283 211 591 264 63 700 234 286 331 228 77 167 128 15 504.1 5 986.1 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 20 1211–1363104421.2.1 Oneida (East) Reservation, NY------------ 20 1211–1363104421.2.1 ----------------------- District 24 261 036 202 380 934 46 900 489 264 1 055 734 234 368 291 32 097.8 12 393.0 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 754 634 561 45 000 64 184 485 342 106 140 124 49.2 19.0 St. -

Community Engagement Plan

Appendix 2-A: Community Engagement Plan Community Engagement Plan Cider Solar Farm Towns of Oakfield and Elba, Genesee County, New York Updated October 2020 Prepared for: Hecate Energy Cider Solar LLC 621 West Randolph Street Chicago, IL 60661 Prepared by: Stantec Consulting Services Inc. 61 Commercial Street, Suite 100 Rochester, New York 14614-1009 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PLAN Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS .....................................................................................................................III 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................1.1 2.0 PROJECT OVERVIEW ................................................................................................2.1 2.1 COMPANY PROFILE ...................................................................................................2.1 2.2 PROJECT SITING AND LOCATION ............................................................................2.1 2.3 PROJECT SUMMARY ................................................................................................. 2.2 2.4 PROJECT BENEFITS ..................................................................................................2.2 3.0 IDENTIFICATION OF STAKEHOLDERS .....................................................................3.1 3.1 REPRESENTATIVE STATE AND FEDERAL AGENCIES ............................................3.2 3.2 LOCAL AGENCIES AND GOVERNMENTS ................................................................ -

Craft Masonry in Genesee & Wyoming County, New York

Craft Masonry in Genesee & Wyoming County, New York Compiled by R.’.W.’. Gary L. Heinmiller Director, Onondaga & Oswego Masonic Districts Historical Societies (OMDHS) www.omdhs.syracusemasons.com February 2010 Almost all of the land west of the Genesee River, including all of present day Wyoming County, was part of the Holland Land Purchase in 1793 and was sold through the Holland Land Company's office in Batavia, starting in 1801. Genesee County was created by a splitting of Ontario County in 1802. This was much larger than the present Genesee County, however. It was reduced in size in 1806 by creating Allegany County; again in 1808 by creating Cattaraugus, Chautauqua, and Niagara Counties. Niagara County at that time also included the present Erie County. In 1821, portions of Genesee County were combined with portions of Ontario County to create Livingston and Monroe Counties. Genesee County was further reduced in size in 1824 by creating Orleans County. Finally, in 1841, Wyoming County was created from Genesee County. Considering the history of Freemasonry in Genesee County one must keep in mind that through the years many of what originally appeared in Genesee County are now in one of other country which were later organized from it. Please refer to the notes below in red, which indicate such Lodges which were originally in Genesee County and would now be in another county. Lodge Numbers with an asterisk are presently active as of 2004, the most current Proceedings printed by the Grand Lodge of New York, as the compiling of this data. Lodges in blue are or were in Genesee County. -

Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE December 2015 Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York Judd David Olshan Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Olshan, Judd David, "Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 399. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/399 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract: Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York Historians follow those tributaries of early American history and trace their converging currents as best they may in an immeasurable river of human experience. The Butlers were part of those British imperial currents that washed over mid Atlantic America for the better part of the eighteenth century. In particular their experience reinforces those studies that recognize the impact that the Anglo-Irish experience had on the British Imperial ethos in America. Understanding this ethos is as crucial to understanding early America as is the Calvinist ethos of the Massachusetts Puritan or the Republican ethos of English Wiggery. We don't merely suppose the Butlers are part of this tradition because their story begins with Walter Butler, a British soldier of the Imperial Wars in America. -

Ohero:Kon “Under the Husk” Konon:Kwe, Haudenosaunee Confederacy

Ohero:kon “Under the Husk” Konon:kwe, Haudenosaunee Confederacy The teenage years are an exciting but challenging phase of life. For Native youth, racism and mixed messages about identity can make the transition to adulthood particularly fraught, and may even lead to risky or self-destructive behavior. Within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, a groundbreaking initiative to restore rites of passage for youth has engaged the entire community. The Ohero:kon ceremonial rite guides youth through Mohawk practices and teachings in the modern context, strengthening their cultural knowledge, self-confidence, and leadership skills. A Loss of Connection Located along the Saint Lawrence River, Akwesasne is home to approximately 13,000 Mohawks. A complex mix of governments exercise jurisdiction over its territory. The international border between the United States and Canada bisects Akwesasne lands, and the community shares a geography with two Canadian provinces (Ontario and Quebec) and one US state (New York). Within the community, there are two externally recognized governments—the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, recognized by the US government, and the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, recognized by the Canadian government—and two longhouse (traditional) governments. Additionally, the Mohawk people are part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, which has a rich presence throughout the region. Incompatibility between the robust governance institutions and the policies of the colonizing governments has led to intense and, at times, violent political polarization within the community. Because of these schisms, the Mohawk people have found it difficult to resolve or even address many pressing social and governmental issues. The proliferation of contradicting laws, moral codes, and standards of behavior is another result, which fuels further divisions.