Oronhyatekha, Baptized Peter Martin, Was a Mohawk, Born and Raised at Six Nations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of PCB Contamination on the Environment and the Cultural Integrity of the St

University of Vermont UVM ScholarWorks Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2015 Effects of PCB Contamination on the Environment and the Cultural Integrity of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe in the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne Kim Ellen McRae University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons Recommended Citation McRae, Kim Ellen, "Effects of PCB Contamination on the Environment and the Cultural Integrity of the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe in the Mohawk Nation of Akwesasne" (2015). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 522. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/522 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at UVM ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of UVM ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTS OF PCB CONTAMINATION ON THE ENVIRONMENT AND THE CULTURAL INTEGRITY OF THE ST. REGIS MOHAWK TRIBE IN THE MOHAWK NATION OF AKWESASNE A Dissertation Presented by Kim McRae to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Specializing in Natural Resources May, 2015 Defense Date: May, 2015 Thesis Committee: Saleem Ali, Ph.D., Advisor Cecilia Danks, Ph.D., Co-Advisor Susan Comerford, Ph.D., Chair Glenn McRae, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of Graduate College ABSTRACT The following research project examines the effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on the environment and the cultural integrity of the St. -

Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Environment Division Environmental Assessment Form Project Name: St. Regis River Water Main Crossing P

Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Environment Division Environmental Assessment Form Project Name: St. Regis River Water Main Crossing Project Developer: Colleen Thomas, Director, Planning & Infrastructure Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Project Coordinator: Rob Henhawk, Field Superintendant Brent Herne, Construction Manager Address: 2817 State Route 95 Akwesasne NY 13655 Phone Number: 1-518-358-4205 FAX Number: 1-518-358-5919 Other Contacts: Shawn Martin Manager, Public Works Aaron Jarvis, Tisdel Associates, Project Engineer 1 © Copyright 2007 St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, or its Licensors. All rights reserved. Introduction It is the tradition of the Mohawk People to look seven generations ahead in making decisions that affect the community. It is in this spirit that the Environmental Review Process has been developed. The resources available on the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation are limited and dwindling with each year that passes. It is the intention of this process to increase awareness of available resources and ensure that all consideration of these resources is taken when initiating a project. Focus and vigilance are required to make sure the seventh generation will have all that is necessary to maintain and continue our way of life. This community is unique and consists of cultural resources that have survived countless efforts to eliminate them and they are deserving of our protection and care. Development can proceed and remain in harmony with the cultural values passed on to us by our ancestors, but it requires forethought and effort. The land and resources should be considered as a gift to pass down to future generations, and as such it should remain as whole, intact, and healthy as it was received so that it may sustain them. -

2020 a Sentimental Journey

0 1 3 Lifescapes is a writing program created to help people tell their life stories, to provide support and guidance for beginner and experienced writers alike. This year marks our thirteenth year running the program at the Brantford Public Library, and A Sentimental Journey is our thirteenth collection of stories to be published. On behalf of Brantford Public Library and this year’s participants, I would like to thank lead instructor Lorie Lee Steiner and editor Shailyn Harris for their hard work and dedication to bringing this anthology to completion. Creating an anthology during a pandemic has been a truly unprecedented experience for everyone involved. Beyond the stress and uncertainty of facing a global contagion, our writers lost the peer support of regular meetings and access to resources. Still, many persevered with their writing, and it is with considerable pride and triumph that I can share the resulting collection of memories and inspiration with you. I know that many of us will look back at 2020 and remember the hardship, the fear, and the loss. It is more important than ever to remember that we – both individually and as a society – have persevered through hard times before, and we will persevere through these times as well. As you read their stories, be prepared to feel both the nostalgia of youth and the triumph of overcoming past adversity. Perhaps you will remember your own childhood memories of travelling with your family, or marvel at how unexpected encounters with interesting people can change perspective and provide insight … and sometimes, change the course of a life. -

Rhetorical Gardening: Greening Composition

Rhetorical Gardening: Greening Composition A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School Of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Carla Sarr June 2017 Master of Science in Teaching and Secondary Education, The New School Committee Chair: Laura R. Micciche Abstract Rhetorical Gardening: Greening Composition argues that the rhetorical understanding of landscapes offers a material site and a metaphor by which to broaden our understanding of rhetoric and composition, as well as increasing the rhetorical archive and opportunities for scholarship. An emphasis on material place in composition is of particular value as sustainability issues are among the toughest challenges college students will face in the years to come. Reading landscapes is an interpretive act central to meaningful social action. The dissertation argues that existing work in rhetorical theory and composition pedagogy has set the stage for an ecological turn in composition. Linking ecocomposition, sustainability, cultural geography, and literacy pedagogies, I trace the origins of my belief that the next manifestation of composition pedagogy is material, embodied, place-based, and firmly planted in the literal issues resulting from climate change. I draw upon historical gardens, landscapes composed by the homeless, community, commercial, and guerilla gardens to demonstrate the rhetorical capacity of landscapes in detail. Building from the argument that gardens can perform a rhetorical function, I spotlight gardeners who seek to move the readers of their texts to social action. Finally, I explore how the study of place can contribute to the pedagogy of composition. -

October 2011 Issue of the Calgary Known Soldier Is at the Base of the Memorial

The www.nwfedstamps.org Federated Philatelist Newsletter of the Northwest Federation of Stamp Clubs No. 196, October, 2011 Canadian Remembrance Day 1959 Calgary, Alberta and 1965 Vancouver, British Columbia slogan cancels for Canadian Remembrance Day . — By Gordon Demke McCrae was a Canadian soldier and physician during World War I and wrote the poem in May 1915, following On Remembrance Day, November 11 of each year, the death of a close friend in the second battle of Ypres in Canadians pay special tribute to and remember those who Flanders, Belgium. McCrae, 1872-1918, was himself a sacrificed their lives during the First World War, the Sec- ond World War, the Korean War, and all other conflicts casualty of that war, dying in France in January 1918, dur- in which members of the Canadian armed forces have ing the final year of the war. participated. — Continued on page 2 The poppy is an important symbol of Remembrance Day and comes from John McCrae’s famous poem In Flanders Fields : In this Issue In Flanders Fields the poppies blow Canadian Remembrance Day………………….. 1 Between the crosses row on row, From the Editor’s Desk …..…………………….. 3 That mark our place; and in the sky Striking First Issue Revenue Coincidence……. 4 The larks, still bravely singing, fly The Early Days of Stamp Collecting…………... 5 Scarce heard amid the guns below. Richard W. Helbock…………………………….. 6 British Columbia Philatelic Society……………. 7 2011 Show Schedule……………………………... 8 October, 2011 — No. 196 The Federated Philatelist 1 Canadian Stamps of Remembrance (continued from page 1) 1968 Canadian stamp commemorating the 50th anniversary of John McCrae’s death. -

Memorials and Memories

MEDALS AND MEMORIES Memorials and Memories Character Education • Explore Canadian memorials and the purpose of remembering • Integrate the past into the student’s present • Build character education upon local experiences Facts selves very clearly in a can-do light that day. A Canadian identify was forged in the fighting at Vimy Ridge and it was • There are cenotaphs and war memorials throughout only fitting that a Canadian memorial was built there. Ontario communities from Aylmer, Orono, North Bay and Port Colborne to Tavistock and Temagimi The Canadian government announced in 1920 that they had acquired the land at the highest point of the ridge. In • The Book of Remembrance in the Peace Tower in Dec. 1922, the government concluded an agreement with Ottawa contains the names of over 112,000 Canadians France that granted Canada the use of 250 acres of land killed in wars since the 19th century on Vimy Ridge in recognition of Canada’s war effort. • When the Vimy Ridge monument was dedicated in Walter Seymour Allward’s design was selected from a July 26, 1936 there were as many people present as Canadian sculpture competition. In 1936, when the sculp- there had been at the battle April 9, 1917 ture was finally ready for unveiling, five trans-Atlantic liners departed from Montreal, bringing over 6,400 people from Before the Reading all over Canada. 1,365 Canadian sailed from Britain. In • List all the local area cenotaphs and war memorials in total, there were over 50,000 Canadian, British and your community and surrounding area. Where are they French veterans and their families present when King located in your community? Edward VIII, King of Canada, unfurled the Union Jack from an imposing figure carved out of single 30 tonne • Discuss the design of the cenotaph or war memorial EMORIES block of stone. -

Trauma and Survival in the Contemporary Church

Trauma and Survival in the Contemporary Church Trauma and Survival in the Contemporary Church: Historical Responses in the Anglican Tradition Edited by Jonathan S. Lofft and Thomas P. Power Trauma and Survival in the Contemporary Church: Historical Responses in the Anglican Tradition Edited by Jonathan S. Lofft and Thomas P. Power This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Jonathan S. Lofft, Thomas P. Power and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6582-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6582-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Jonathan S. Lofft and Thomas P. Power Chapter One ................................................................................................ 9 Samuel Hume Blake’s Pan-Anglican Exertions: Stopping the Expansion of Residential and Industrial Schools for Canada’s Indigenous Children, 1908 William Acres Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

Before Albany

Before Albany THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University ROBERT M. BENNETT, Chancellor, B.A., M.S. ...................................................... Tonawanda MERRYL H. TISCH, Vice Chancellor, B.A., M.A. Ed.D. ........................................ New York SAUL B. COHEN, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. ................................................................... New Rochelle JAMES C. DAWSON, A.A., B.A., M.S., Ph.D. ....................................................... Peru ANTHONY S. BOTTAR, B.A., J.D. ......................................................................... Syracuse GERALDINE D. CHAPEY, B.A., M.A., Ed.D. ......................................................... Belle Harbor ARNOLD B. GARDNER, B.A., LL.B. ...................................................................... Buffalo HARRY PHILLIPS, 3rd, B.A., M.S.F.S. ................................................................... Hartsdale JOSEPH E. BOWMAN,JR., B.A., M.L.S., M.A., M.Ed., Ed.D. ................................ Albany JAMES R. TALLON,JR., B.A., M.A. ...................................................................... Binghamton MILTON L. COFIELD, B.S., M.B.A., Ph.D. ........................................................... Rochester ROGER B. TILLES, B.A., J.D. ............................................................................... Great Neck KAREN BROOKS HOPKINS, B.A., M.F.A. ............................................................... Brooklyn NATALIE M. GOMEZ-VELEZ, B.A., J.D. ............................................................... -

Howitzer Task Force.Pdf

MEMORANDUM Date: February 7, 2020 To: Vice-Chairs and Members Restoration of the Field Howitzer Task Force From: Sara Munroe, Manager of Tourism, Culture & Sport CC: Brian Hutchings, Chief Administrative Officer Kevin Finney, Director, Economic Development & Tourism Brian Hughes, Director, Parks Services Tanya Daniels, City Clerk and Director of Clerks Services Vicki Armitage, Manager, Parks Services RE: Recommended Process for Brant War Memorial Monument, Park and WWII Monument Projects At its meeting on January 27, 2020, the Restoration of the Field Howitzer Task Force made the following (draft) resolution: Moved by Councillor McCreary Seconded by Councillor Carpenter THAT staff BE DIRECTED to: 1. Investigate and cost the completion of the Brant War Memorial Monument as originally designed; and 2. Relocate the WWII bronze figures to a prominent location where they will be the focal point; and 3. Investigate and add the missing names of veterans to the Cenotaph and confirm with Veteran’s Affairs as to whether they should be on the existing monument; and 4. Redesign the park to accommodate the use of the portable bleachers and built in seating. CARRIED UNANIMOUSLY Staff Report Staff Report 2019-500 (Appendix A) includes information about how to undertake the process to have this work completed. At this time, a Task Force report to Council, identifying funding to complete the preparation work, must be completed for staff to move forward with the above resolution. Cost and Completion of the Brant War Memorial Walter Allward’s original maquette for the Brant War Memorial included two bronze figures that were not included when the original monument was unveiled in 1933. -

Researching Aboriginal Ancestors

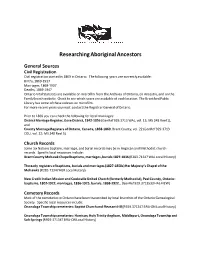

Researching Aboriginal Ancestors General Sources Civil Registration Civil registration started in 1869 in Ontario. The following years are currently available: Births, 1869-1917 Marriages, 1869-1937 Deaths, 1869-1947 Ontario Vital Statistics are available on microfilm from the Archives of Ontario, on Ancestry, and on the FamilySearch website. Check to see which years are available at each location. The Brantford Public Library has some of these indexes on microfilm. For more recent years you must contact the Registrar General of Ontario. Prior to 1869 you can check the following for local marriages: District Marriage Register, Gore District, 1842-1856 (GenRef 929.3713 WAL, vol. 13; MS 248 Reel 1), and County Marriage Registers of Ontario, Canada, 1858-1869, Brant County, vol. 22 (GenRef 929.3713 COU, vol. 22; MS 248 Reel 5) Church Records Some Six Nations baptism, marriage, and burial records may be in Anglican and Methodist church records. Specific local resources include: Brant County Mohawk Chapel baptisms, marriages, burials 1827-1836 (R283.71347 WAL Local History) The early registers of baptisms, burials and marriages (1827-1850s) Her Majesty’s Chapel of the Mohawks (R283.71347 HER Local History) New Credit Indian Mission and Cooksville United Church (formerly Methodist), Peel County, Ontario: baptisms, 1802-1922, marriages, 1836-1925, burials, 1868-1922… (GenRef 929.3713533 HAL-NEW) Cemetery Records Most of the cemeteries in Ontario have been transcribed by local branches of the Ontario Genealogical Society. Specific local resources include: Onondaga Township cemeteries: Baptist Church and Pleasant Hill (R929.371347 BRA-ON Local History) Onondaga Township cemeteries: Harrison, Holy Trinity Anglican, Middleport, Onondaga Township and Salt Springs (R929.371347 BRA-ON Local History) Tuscarora Township Indian burial sites, Ontario Genealogical Society. -

Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE December 2015 Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York Judd David Olshan Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Olshan, Judd David, "Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 399. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/399 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract: Butlers of the Mohawk Valley: Family Traditions and the Establishment of British Empire in Colonial New York Historians follow those tributaries of early American history and trace their converging currents as best they may in an immeasurable river of human experience. The Butlers were part of those British imperial currents that washed over mid Atlantic America for the better part of the eighteenth century. In particular their experience reinforces those studies that recognize the impact that the Anglo-Irish experience had on the British Imperial ethos in America. Understanding this ethos is as crucial to understanding early America as is the Calvinist ethos of the Massachusetts Puritan or the Republican ethos of English Wiggery. We don't merely suppose the Butlers are part of this tradition because their story begins with Walter Butler, a British soldier of the Imperial Wars in America. -

Ohero:Kon “Under the Husk” Konon:Kwe, Haudenosaunee Confederacy

Ohero:kon “Under the Husk” Konon:kwe, Haudenosaunee Confederacy The teenage years are an exciting but challenging phase of life. For Native youth, racism and mixed messages about identity can make the transition to adulthood particularly fraught, and may even lead to risky or self-destructive behavior. Within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, a groundbreaking initiative to restore rites of passage for youth has engaged the entire community. The Ohero:kon ceremonial rite guides youth through Mohawk practices and teachings in the modern context, strengthening their cultural knowledge, self-confidence, and leadership skills. A Loss of Connection Located along the Saint Lawrence River, Akwesasne is home to approximately 13,000 Mohawks. A complex mix of governments exercise jurisdiction over its territory. The international border between the United States and Canada bisects Akwesasne lands, and the community shares a geography with two Canadian provinces (Ontario and Quebec) and one US state (New York). Within the community, there are two externally recognized governments—the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, recognized by the US government, and the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, recognized by the Canadian government—and two longhouse (traditional) governments. Additionally, the Mohawk people are part of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, which has a rich presence throughout the region. Incompatibility between the robust governance institutions and the policies of the colonizing governments has led to intense and, at times, violent political polarization within the community. Because of these schisms, the Mohawk people have found it difficult to resolve or even address many pressing social and governmental issues. The proliferation of contradicting laws, moral codes, and standards of behavior is another result, which fuels further divisions.