Earth Vernacular Architecture in the Western Desert of Egypt Dabaieh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Materials & Construction

INTERMEDIATE VOCATIONAL COURSE SECOND YEAR BUILDING MATERIALS & CONSTRUCTION FOR THE COURSE OF WATER SUPPLY AND SANITARY ENGINEERING STATE INSTITUTE OF VOCATIONAL EDUCATION DIRECTOR OF INTERMEDIATE EDUCATION GOVT. OF ANDHRA PRADESH 2006 Intermediate Vocational Course, 2nd Year : Building Materials and Construction (For the Course of Water Supply and Sanitary Engineering) Author : Sri P. Venkateswara Rao & M.Vishnukanth, Editor : Sri L. Murali Krishna. © State Institute of Vocational Education Andhra Pradesh, Hyderabad. Printed and Published by the Telugu Akademi, Hyderabad on behalf of State Institute of Vocational Education Govt. of Andhra Pradesh, Hyderabad. First Edition : 2006 Copies : All rights whatsoever in this book are strictly reserved and no portion of it may be reproduced any process for any purpose without the written permission of the copyright owners. Price Rs: /- Text Printed at …………………… Andhra Pradesh. AUTHOR Puli Venkateshwara Rao, M.E. (STRUCT. ENGG.) Junior Lecturer in Vocational, WS & SE Govt. Junior College, Malkajgiri, Secunderabad. & M. VISHNUKANTH, B.TECH.(Civil) Junior Lecturer in Vocational, WS & SE Govt. Junior College, Huzurabad, Karimnagar Dist. EDITOR L. MURALI KRISHNA, M.TECH.(T.E.) Junior Lecturer in Vocational, CT Govt. Junior College, Ibrahimpatnam, Ranga Reddy Dist. IVC SECOND YEAR BUILDING MATERIALS & CONSTRUCTION STATE INSTITUTE OF VOCATIONAL EDUCATION WATER SUPPLY AND SANITARY ENGINEERING DIRECTOR OF INTERMEDIATE EDUCATION GOVT. OF ANDHRAPRADESH REFERENCE BOOKS 1. BUILDING MATERIAL - RANGAWALA 2. BUILDING MATERIAL - SUSHIL KUMAR 3. BUILDING MATERIALS & CONSTRUCTION - B.P.BINDRA 4. BUILDING CONSTRUCTION - B.C.RANGAWALA 5. BUILDING MATERIALS - A.KAMALA MODEL PAPER BUILDING MATERIALS AND CONSTRUCTION Time : 3 hrs Max Marks : 50 SECTION – A Note: 1) Attempt all questions 2) Each question carries 2 marks 10x2=20 1. -

Building Material Reuse Guide

Sonoma County Waste Management Agency 2300 County Center Drive, Suite B-100 Santa Rosa, California 95403 Building Materials Reuse Guide Look for your Recycling Guide in the AT&T Phone Book under Recycling. Builders’ Guide on-line at www.RecycleNow.org appliances doors cabinets electrical fencing hardware lumber plumbing tile windows updated: 9.29.08 ECO-DESK 565-DESK(3375) www.RecycleNow.org Funding Provided by a Grant from the California Integrated Waste Management Board. Zero Waste—You Make it Happen! IN T E G R A T E D PRINTED ON 100% POST-CONSUMER (PC) FIBER PAPER for Sonoma County W A S T E M A N A G E M E N T B O A R D Appliances Doors Cabinets Electrical Fencing Flooring Hardware Lumber Plumbing, Sheetrock/ Tile Windows Facility newer than (bath & fixtures & & tools fixtures & drywall accepts Reuse Building Materials 5 years kitchen) supplies supplies mixed loads of Free classified ads The following chart lists organizations that construction to help manage promote the salvage or reuse of good building & demolition materials. Some are nonprofits that offer debris for your building charitable receipts for donations. recycling material discards. Beyond Waste Tu-F 9-1 605 West Sierra, Cotati.........................792-2555 & by appt. TT TT T T Materials Exchange Daniel O. Davis, Inc. M-F 7:30-5. 1051 Todd Rd., Santa Rosa...................585-1903 TT TT T T Central Disposal Site (Reuse area) Daily 500 Mecham Rd, Petaluma..................795-3660 7-3:30. TTTTTTTTT TT Browse the SonoMax listings. Post a new ad— Global Material Recovery Services M-Sa 7-5, Search the available available or wanted. -

Megastructures: Steel, Brick and Concrete

Megastructures: Steel, Brick and Concrete 3 x 60’ EPISODIC BREAKDOWN 1. Steel It is one of the strongest materials on earth. It has changed the course of history and altered human civilization. From the soaring skylines in a vast metropolis…to dinner tables across the world and razor sharp tools responsible for medical miracles: Steel has defined life as we know it. MegaStructures: The Science of Steel will bring viewers face to face with this magical material that serves as the strength behind urban infrastructure, epic skyscrapers and everyday objects that shape our world. Our cameras will go inside the mills of U.S. Steel to see how this incredible invention of man is born and also visit such historic steel structures as the Brooklyn Bridge, the Empire State Building, and the Gateway Arch. This program will explore steel, from its grandest achievements to the simplest tools of life. How It’s Built: Steel will display why steel makes the impossible, possible. 2. Brick Brick: baptized in fire to be rock-hard – and prized because it is fire-proof. Brick has become an icon in our culture. You start with a block you can hold in your hand, but when you lay 10 or 20 million, they add up to a soaring structure: MegaStructures: The Science of Brick will take the viewer from the earliest man-made buildings to the 21st Century’s green/eco-friendly building movement, all while highlighting the inspiring buildings and monuments that this remarkable material has made possible. 3. Concrete It is the most-used building material on Earth. -

Building Materials

JUNE 2019 Building Materials VOLUME 301 A FAR CRY FROM LAST YEAR DOMESTIC DEMAND CAUTION ABOUNDS HARDWOOD TUMULT The optimism persisting on the Wary of further price drops, The domestic hardwood market domestic construction market over the market participants limit purchasing is working to cope with falling past few years is waning, despite the export demand impending building season MONITOR BUILDING MATERIALS VOLUME GREATAMERICAN.COM In This Issue JUNE 2019 800-45-GREAT 301 Building Materials Reference Trend Tracker 03 10 Sheet 05 Overview 11 Monitor Information 06 Softwood Lumber 12 Experience 07 Softwood Panels 13 Appraisal & Valuation Team 08 Hardwood Lumber 14 About Great American Lumber and Woodworking 09 Equipment Deals are a moving target. A constantly shifting mix of people, numbers and timing. We’re here to simplify this process for you. Our experts are dedicated to tracking down and flushing out the values you need even on the most complex deals, so you can leverage our hard-won knowledge to close the deal. © 2019 Great American Group, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Trend Tracker - Inventory Market Prices Lumber Building Materials Three Months Year NOLVs Decreasing Decreasing Sales Trends Decreasing Increasing Softwood Decreasing Decreasing Gross Margin Decreasing Mixed Hardwood Increasing Decreasing Inventory Mixed Increasing NOLVS • Building materials: Gross margins have been mixed, as • Lumber: NOLVs generally declined over the past quarter prices for items such as wallboard and vinyl siding have and versus the prior year as pricing declined from the climbed, in some cases due to tariffs for products such as mid-2018 peak as a result of lower demand and higher steel studs and tracks. -

Building Products & Materials Industry Update

BUILDING PRODUCTS & MATERIALS INDUSTRY UPDATE │ AUGUST 2015 www.harriswilliams.com Investment banking services are provided by Harris Williams LLC, a registered broker-dealer and member of FINRA and SIPC, and Harris Williams & Co. Ltd, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Harris Williams & Co. is a trade name under which Harris Williams LLC and Harris Williams & Co. Ltd conduct business. 0 BUILDING PRODUCTS & MATERIALS INDUSTRY UPDATE │ AUGUST 2015 BUILDING PRODUCTS & MATERIALS GROUP OVERVIEW CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . WHAT WE’RE READING Harris Williams & Co. is pleased to present our Building Products and Materials . PUBLIC MARKETS Industry Update for August 2015. This report provides commentary and analysis on . PUBLIC COMPARABLES current capital market trends and merger and acquisition dynamics within the . M&A ACTIVITY global building products and materials industry. We hope you find this edition helpful and encourage you to contact us directly if you would like to discuss our perspective on current industry trends and M&A opportunities or our relevant industry experience. CONTACTS Mike Hogan OUR PRACTICE Managing Director [email protected] Harris Williams & Co. is a leading advisor to the building products and materials +1 (804) 915-0104 industry. Our significant experience covers a broad range of end markets, industries, and business models. Ryan Nelson Managing Director [email protected] Distribution & Construction Building Products +1 (804) 915-0121 Services Materials . Acoustical . Roofing . Architectural and . Aggregates Trey Packard . Cabinets and . Siding . Engineering . Asphalt Vice President . Countertops . Tools and Hardware . Installation and . Aluminum [email protected] . Carpet and Flooring . Windows and Doors . Contracting . Bricks +1 (804) 887-6016 . -

Bero Architecture PLLC BA915.32.Construction Quality.04512.Doc Some Thoughts on Construction Quality

B E R O ARCHITECTURE P L L C ARCHITECTURE SUSTAINABILITY PRESERVATION Thirty Two Winthrop Street, Rochester, New York 14607 585-262-2035 (phone) • 585-262-2054 (fax) • [email protected] (email) SOME THOUGHTS ON CONSTRUCTION QUALITY Quality Options Building construction varies in quality. The following list is arranged from modest conventional quality to the highest quality: residential, commercial, institutional, and museum. Residential quality is least expensive, least durable and most susceptible to destruction by natural forces. We urge owners of other than residential buildings (especially organizations planning to own their buildings beyond an individual human life time) to implement at least institutional quality construction and repairs. Conventional Wisdom As day-to-day decisions are made regarding how to repair your building, beware of conventional wisdom. Conventional wisdom is the basis of advice promulgated by suppliers and contractors who are engaged in conventional construction, most of which is residential or light commercial. The fundamental premise is that cost is of utmost importance and durability is secondary. Since average home ownership is reputed to last only seven years, conventional wisdom may be appropriate for many homeowners. But for individuals or organizations planning to preserve a building, replacing sound original materials with short-lived materials is almost always a bad idea, for example, replacing wood windows with vinyl windows. Similarly, use of temporary materials like aluminum flashing and pressure-treated wood is ultimately more expensive than use of more durable materials. When planning repairs and improvements you may wish to seek durability and analyze costs vs. benefits over time, as befits preservation of a significant building. -

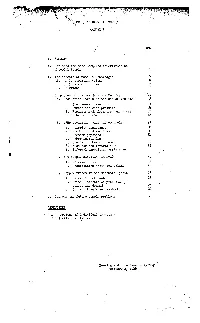

Building Material Supply

CONTENTS Page r. summary 1 II. The need for more adequate infonnation on Material Supply 4 III. The effects •f material shortages 6 A. On Construction Volume 6 B, On Construction Time 6 c. On Prices 7 IV. Supply and price trends since V-J Day 13 A. Production levels at the end of the war 13 1. The general level 13 2. Lumber and wood products 14 3. Preducts made from iron and steel 17 4. Other products 18 B. VEHP production aids and controls 19 1. Priority assistance 20 2. Production directives 20 3. Premium payments 21 :1 Labor recruiting 22 4. )1 , s~ Special lumber programs 22 6. Aids f•r new materials 23 7. Infonnal expediting assistance 23 • c. The supply situation in 1946 23 1. Materials output 23 2. Construction costs and volume 24 n. Supply trends in the decontrol peri•d 25 1. Relaxation of centrals 25 2. Initial effects on production, prices and demand 26 3. Current trends and eutlook 27 v. Current and future supply problems 30 APPENDIXES A. Preblems ef individual materials B. statistical tables Rsusing and Home Finance Agency Februar.r 4, 1948 ...... ..,1!11!'19! ..U-""l!lllll .... -•1111!1•t'l!llt. •a _u...,.:.. !l!l!!h""H-. ..,+,...,,.., --"""'""''-•-.~.,.......,.....,..._.,,,__ . ..,,.,..,...,.,""". ~.,.... """'""' ·-· _......,, ·-x•-1'*'°"""'.1. -·•-••¥.1'24111!11!u;t!ll'P.. !ll!!t!lll .. tl!!!'J!!!!!Hl!!l!M" . l!IJ... llJ!l.MUl!Q!ll!l!#llllll 1111!!.,[email protected]•™·- · ~ .. ~ _,,,~~ ! BUILDING W\.TERIAL SUPPLY I, SUMMARY Building material shortages were the primary: limj.ting factors in the volUi~e of housing construction immediately after the end of the war; and at the present time more than two years cU'ter v ... -

Commercial Building Material Reference Guide

COMMERCIAL BUILDING MATERIAL REFERENCE GUIDE DRYWALL ■ STEEL STUDS ■ CEILING SYSTEMS ■ INSULATION ■ COMMERCIAL DOORS & HARDWARE LOCATIONS WITH LARGEST COMMERCIAL BUILDING MATERIAL INVENTORY SUCCASUNNA, NJ: 33 ROUTE 10 EAST, SUCCASUNNA, NJ 07876 – (973) 968-7700 EMERSON, NJ: 246 KINDERKAMACK RD, EMERSON, NJ 07630 – (201) 262-6666 GARFIELD, NJ: 485 RIVER DR., GARFIELD, NJ 07026 – (973) 772-0044 NEWARK, NJ: 500 DOREMUS AVE., NEWARK, NJ 07105 – (973) 638-7200 KUIKENBROTHERS.COM/COMMERCIAL KUIKEN BROTHERS COMPANY, INC is a full service residential and commercial building material supplier serving the greater New York and New Jersey market. Our core customers are small and large general contractors, developers, subcontractors, builders and remodelers. The following pages feature our stock and readily available commercial materials that are most commonly used in mid-rise/ mixed use, multi-family, office buildings, hospitals, schools/ university and retail projects. PRODUCTS: ■ Drywall ■ Heavy & Light Gauge Metal Studs ■ Drywall Compounds & Accessories ■ Lumber & Plywood ■ Fasteners & Adhesives ■ Engineered Lumber & Truss Systems ■ Ceiling Tiles & Suspension Systems ■ Commercial Door & Hardware ■ FRP Panels ■ Windows Doors, Moulding, Cabinetry ■ Insulation & Vapor Barriers SERVICES: ■ Boom Delivery 4, 6 & 8 story ■ Jobsite Consultations ■ Moffet Truck Mounted Forklift ■ Large Product Inventory ■ Project Management ■ 9 Locations in NJ & NY While we have made every effort to portray each item in this guide as accurately as possible, adjustments to our in-stock inventory may occur, or certain items may be discontinued. Always check current availability with a Kuiken Brothers sales representative. GARFIELD, NJ KUIKENBROTHERS.COM/COMMERCIAL 1 Metal Studs (HEAVY & LIGHT GAUGE FRAMING) Steel stud construction has been the standard for commercial and multi- family projects for years. -

Building a Better World

BUILDING A BETTER WORLD Eliminating Unnecessary PFAS in Building Materials This report was developed by the Green Science Policy Institute, whose mission is to facilitate safer use of chemicals to protect human and ecological health. Learn more at www.greensciencepolicy.org AUTHORS Seth Rojello Fernández, Carol Kwiatkowski, Tom Bruton EDITORS Arlene Blum, Rebecca Fuoco, Hannah Ray, Anna Soehl EXTERNAL REVIEWERS* Katie Ackerly (David Baker Architects) Brent Ehrlich (BuildingGreen) Juliane Glüge (ETH Zurich) Jen Jackson (San Francisco Department of the Environment) David Johnson (SERA Architects) Rebecca Staam (Healthy Building Network) DESIGN Allyson Appen, StudioA2 ILLUSTRATIONS Kristina Davis, University of Notre Dame * External reviewers provided helpful comments and discussion on the report but do not endorse the factual nature of the content. THE BUILDING INDUSTRY HAS THE WILL AND THE KNOW-HOW TO REDUCE ITS USE OF PFAS CHEMICALS. UNDERSTANDING WHERE PFAS ARE USED AND FINDING SAFER ALTERNATIVES ARE CRITICAL. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 7 List of Abbreviations 8 Background 9 PFAS in Humans and the Environment 11 Health Hazards of PFAS 11 Who is at Risk? 12 Non-essential Uses 13 PFAS Use in Building Materials 14 Roofing 17 Coatings 20 Flooring 22 Sealants and Adhesives 24 Glass 25 Fabrics 26 Wires and Cables 27 Tape 28 Timber-Derived Products 28 Solar Panels 29 Artificial Turf 29 Seismic Damping Systems 30 From Building Products to the Environment 32 Moving forward 32 Managing PFAS as a Class 32 The Need for Transparency 34 Safer Alternatives 35 What Can You Do? 36 List of References 45 Appendix 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 er- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) consumers and some governments are call- are synthetic chemicals that are useful in ing for limits on the production and use of P many building materials and consumer all PFAS, except when those uses are truly products but have a large potential for harm. -

The Potential Role of Cattail-Reinforced Clay Plaster in Sustainable Building

The potential role of cattail-reinforced clay plaster in sustainable building G. Georgiev, W. Theuerkorn, M. Krus, R. Kilian and T. Grosskinsky Fraunhofer-Institute for Building Physics IBP Holzkirchen, Germany _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY Sustainable development is a key goal in town and country planning, as well as in the building industry. The main aims are to avoid inefficient land use, to improve the energy efficiency of buildings and, thus, to move towards meeting the challenges of climate change. In this article we consider how the use of a traditional low-energy building material, namely clay, might contribute. Recent research has identified a promising connection between the reinforcement of clay for internal wall plastering with fibres from the wetland plant Typha latifolia (cattail) and the positive environmental effects of cultivating this species. If large quantities of Typha fibres were to be used in building, the need for cultivation of the plant would increase and create new possibilities for the renaturalisation of polluted or/and degraded peatlands. We explore the topic first on the basis of literature, considering the suitability of Typha for this application and possibilities for its sustainable cultivation, as well as implications for the life cycle analyses of buildings in which it is used. We then report (qualitatively) the results of testing different combinations of clay with natural plant (straw and cattail) fibres for their suitability as a universal plaster, which demonstrate clearly the superior properties of Typha fibres as a reinforcement material for clay plaster mortars. KEY WORDS: clay mortar; life cycle analysis; paludiculture; peatland; Typha latifolia; wetland _______________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION clay has already been proved as a sustainable building material. -

Construction Manual for Earthquake-Resistant Houses Built Of

Gernot Minke Construction manual for earthquake-resistant houses built of earth Published by GATE - BASIN (Building Advisory Service and Information Network) at GTZ GmbH (Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit) P.O.Box 5180 D-65726 Eschborn Tel.: ++49-6196-79-3095 Fax: ++49-6196-79-7352 e-mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.gtz.de/basin December 2001 Contents Acknowledgement 4 Introduction 5 1. General aspects of earthquakes 6 1.1 Location, magnitude, intensity 6 1.2 Structural aspects 6 2. Placement of house in the case of 8 slopes 3. Shape of plan 9 4. Typical failures, 11 typical design mistakes 5. Structural design aspects 13 6. Rammed earth walls 14 6.1 General 14 6.2 Stabilization through mass 15 6.3 Stabilization through shape of16 elements 6.4 Internal reinforcement 19 7. Adobe walls 22 7.1 General 22 7.2 Internal reinforcement 24 7.3 Interlocking blocks 26 7.4 Concrete skeleton walls with 27 adobe infill 8. Wattle and daub 28 9. Textile wall elements filled with 30 earth 10. Critical joints and elements 34 10.1 Joints between foundation, 34 plinth and wall 10.2 Ring beams 35 10.3 Ring beams which act as roof support 36 11. Gables 37 12. Roofs 38 12.1 General 38 12.2 Separated roofs 38 13. Openings for doors and windows 41 14. Domes 42 15. Vaults 46 16. Plasters and paints 49 Bibliographic references 50 3 Acknowledgement This manual was first published in Spanish within the context of the research and development project Viviendas sismorresistentes en zonas rurales de los Andes, supported by the German organizations Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn (DFG), and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Eschborn (gtz). -

Environmental Profile on Building Material Passports for Hot Climates

sustainability Article Environmental Profile on Building Material Passports for Hot Climates Amjad Almusaed 1,* , Asaad Almssad 2 , Raad Z. Homod 3 and Ibrahim Yitmen 1 1 Department of Construction Engineering and Lighting Science, Jönköping University, 551 11 Jönköping, Sweden; [email protected] 2 Head of Building Technology, Karlstad University Sweden, 651 88 Karlstad, Sweden; [email protected] 3 Department of Oil and Gas Engineering, Basrah University for Oil and Gas, Garmat Ali Campus, Basrah 61004, Iraq; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-70-045-1114 Received: 20 March 2020; Accepted: 27 April 2020; Published: 4 May 2020 Abstract: Vernacular building materials and models represent the construction methods and building materials used in a healthy manner. Local building materials such as gravel, sand, stone, and clay are used in their natural state or with minor processing and cleaning to mainly satisfy local household needs (production of concrete, mortar, ballast, silicate, and clay bricks and other products). In hot climates, the concept of natural building materials was used in a form that can currently be applied in different kinds of buildings. This concept depends on the proper consideration of the climate characteristics of the construction area. A material passport is a qualitative and quantitative documentation of the material composition of a building, displaying materials embedded in buildings as well as showing their recycling potential and environmental impact. This study will consider two usages of building materials. The first is the traditional use of building materials and their importance in the application of vernacular building strategies as an essential global bioclimatic method in sustainable architecture.