Protecting Kentucky Bourbon in the Global Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PASSPORT Kentucky Bourbon Trail® Completion Certification (For Kentucky Distillers’ Association Use Only) Personal Information

© 2018 Kentucky Distillers’ Association. All Rights Reserved. Kentucky Bourbon Trail® is a registered trademark of the Kentucky Distillers’ Association. PASSPORT Kentucky Bourbon Trail® Completion Certification (For Kentucky Distillers’ Association use only) Personal Information REQUIRED – PLEASE PRINT NAME Welcome to the famous Kentucky Bourbon Trail® tour. Here’s your Passport to the world’s greatest Bourbon, with ten legendary DATE OF BIRTH distilleries waiting to share their historic craft and timeless secrets. (MUST BE 21 TO COMPLETE) Collect stamps at all ten distilleries and we’ll send you a free If you would like to pick up your Passport completion souvenir gift to commemorate your journey. Your souvenir Passport will be immediately, follow the directions on the below link: ADDRESS returned along with the gift. Allow 4-6 weeks for delivery. kybourbontrail.com You must be 21 years old to participate. To receive your ADDRESS 2 completion souvenir you may mail your stamped passport to: Kentucky Bourbon Trail Contact us at: 675 Setzer Way CITY / STATE / ZIP CODE Lexington, KY 40508 kybourbontrail.com (Mail only, not a pick-up location.) kybourbontrailshop.com If you would like to pick up your Passport completion souvenir facebook.com/kybourbontrail EMAIL immediately, follow the directions on the below link: (By providing your email you agree to receive updates about your passport and the Kentucky Bourbon Trail® Tour) kybourbontrail.com @kybourbontrail For more information, visit kybourbontrail.com. kybourbon.com PHONE Please savor -

What's New in Kentucky Bourbon

WHAT’S NEW IN KENTUCKY BOURBON Bourbon Events, Distillers, Expansions Enhance Guests’ Experiences 2021 Bourbon Trail™ Passport and Field Guide released – The Kentucky Distillers’ Association recently released the 2021 Bourbon Trail™ Passport and Field Guide, a 150-page document containing all the information needed for planning travel, food, tours, tastings and cocktails, plus tips and tricks about the 37 distilleries that are part of the official Kentucky Bourbon Trail® and Kentucky Bourbon Craft Trail®. The guide will be sold at all distilleries included on the trails, the KBT Welcome Center® and online. New this year, in addition to collecting stamps for visiting and touring spots, the passport will also unlock perks such as private barrel selections, tastings, special barware and access to collectible bottles. https://www.msn.com/en-us/foodanddrink/cocktails/new-bourbon-passport-is-your-perfect-guide-to-the-best-whiskey-in- kentucky/ar-AAKRFQf & https://kybourbontrail.com/field-guide/ African American owned distillery planned for Lexington – African American Lexington entrepreneurs Sean and Tia Edwards plan to build a distillery, music hall, and event center in downtown Lexington. Fresh Bourbon Distilling Co.’s 34,000-square-foot facility will be near the Distillery District, with a likely completion date in late 2021. https://smileypete.com/business/fresh-bourbon-distilling/ B-Line in northern Kentucky adds new stops – On National Bourbon Day, June 14, 2021, the B-Line announced four additions to Northern Kentucky’s bourbon experience. The new stops include Smoke Justis and Libby’s Southern Comfort in Covington, Three Spirits Tavern in Bellevue and The Beehive Augusta Tavern in Augusta. -

(Ka Potheen, Potcheen, Poiteen Või Poitín) – Vis, Dst Samakas

TARTU ÜLIKOOL FILOSOOFIATEADUSKOND GERMAANI, ROMAANI JA SLAAVI FILOLOOGIA INSTITUUT VÄIKE INGLISE-EESTI SELETAV VISKISÕNASTIK MAGISTRITÖÖ Tõnu Soots Juhendaja: Krista Kallis TARTU 2013 Sisukord Sissejuhatus ....................................................................................................................... 3 Terminoloogia valik ja allikad .......................................................................................... 5 Terminoloogilised probleemid ja terminiloome................................................................ 6 Lühidalt viskist ................................................................................................................ 11 Inglise-eesti seletav viskisõnastik ................................................................................... 13 Märgendid ja lühendid ................................................................................................ 13 Kokkuvõte ....................................................................................................................... 75 Kasutatud materjalid ....................................................................................................... 76 Raamatud..................................................................................................................... 76 Veebilehed, artiklid, videod, arutelud, arvutisõnastikud............................................. 77 Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

Cox's Creek Shepherdsville

THE B-LINE 4 11 1 Shelbyville frankfort 7 14 3 13 10 18 SHEPHERDSVILLE 15 17 7 5 5 COX’S CREEK Owensboro 8 12 Elizabethtown 2 6 9 DANVILLE Miles Between Distilleries Angel’s EnvyBardstown BourbonBulleit Distilling CompanyEvan WilliamsCo. Four Experience Roses DistilleryHeaven HillJim Distillery Beam DistilleryLux Row Maker’s MarkMichter’s Distillery FortOld Nelson Forester DistilleryO.Z. Tyler Rabbit HoleStitzel-WellerTown Distillery BranchWilderness Distillery WildTrail TurkeyDistilleryWoodford Distillery Reserve Distillery Angel’s Envy — 3 34 1 60 44 28 44 61 1 1 111 1 5 76 84 57 60 Lebanon 16 Bardstown Bourbon Company 46 — 43 47 47 5 20 3 31 47 45 127 46 48 59 43 43 56 Bulleit Distilling Co. 34 43 — 36 27 44 51 41 54 35 35 143 34 42 46 54 25 28 Evan Williams Experience 1 47 36 — 60 44 28 45 61 1 1 109 2 5 76 86 57 60 Four Roses Distillery 60 47 27 60 — 38 53 37 54 59 59 160 57 64 24 29 8 21 Heaven Hill Distillery 44 5 44 44 38 — 18 4 18 44 42 124 43 45 60 44 45 56 61 Jim Beam Distillery 28 20 51 28 53 18 — 18 35 28 27 121 28 29 74 60 60 71 Lux Row 44 3 41 45 37 4 18 — 15 43 43 127 43 46 58 43 43 55 Maker’s Mark Distillery 61 31 54 61 54 18 35 15 — 59 58 134 58 62 75 34 61 72 Michter’s Fort Nelson Distillery 1 47 35 1 59 44 28 43 59 — 1 108 2 6 78 85 56 60 Old Forester 1 45 35 1 59 42 27 43 58 1 — 109 1 11 76 85 56 60 Pikeville O.Z. -

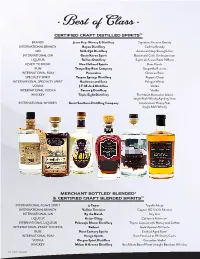

• Best of Class •

• Best of Class • Certified Craft Distilled Spirits™ BRANDY Jaxon Keys Winery & Distillery Signature Reserve Brandy INTERNATIONAL BRANDY Bayon Distillery Cashew Brandy GIN StilL 630 Distillery American Navy Strength Gin INTERNATIONAL GIN Great Karoo Spirit Bossieveld Craft Gin Inspiration LIQUEUR Rollins Distillery Esprit de Krewe Rock ‘N Rum READY TO DRINK New Holland Spirits Rum Punch RUM Tampa Bay Rum Company Gasparilla Reserve INTERNATIONAL RUM Paranubes Oaxacan Rum SPECIALTY SPIRIT Tarpon Springs Distillery Papou’s Ouzo INTERNATIONAL SPECIALTY SPIRIT Rodionov and Sons Polugar Wheat VODKA J.T. Meleck Distillers Vodka INTERNATIONAL VODKA Patent 5 Distillery Vodka WHISKEY Triple Eight Distillery The Notch Nantucket Island Single Malt Whisky Aged 15 Years INTERNATIONAL WHISKEY Great Southern Distilling Company Limeburners Heavy Peat Single Malt Whisky Merchant Bottled1 Blended 2 & Certified Craft Blended Spirits™ 1 INTERNATIONAL AGAVE SPIRIT 4 Copas Tequila Añejo INTERNATIONAL BRANDY Vallein Tercinier Cognac XO Vieille Réserve 1 INTERNATIONAL GIN By the Dutch Dry Gin 1 LIQUEUR Geijer Glögg California Falernum INTERNATIONAL LIQUEUR Pakruojis Manor Distillery Thyme Liqueur with Honey and Saffron INTERNATIONAL READY TO DRINK Bailoni Gold Apricot-Frizzante 2 RUM Next Century Spirits Exalted Aged Rum INTERNATIONAL RUM Virago Spirits Rum Finished in PX Sherry Casks 1 VODKA Oregon Spirit Distillers Cascadian Vodka WHISKEY Milam & Greene Distillery Ben Milam Barrel Proof Straight Bourbon Whiskey 14 distiller • Excellence in Packaging • Best of Category BEST BACKBAR PACKAGING One Eight Distilling Untitled Whiskey No. 13 BEST ECO-PACKAGING Isle of Wight Distillery Mermaid Gin BEST RETAIL PACKAGING Isle of Wight Distillery Mermaid Gin Brand Identity GOLD Blackland Distillery Graton Spirits Company Hotel Tango Distillery SILVER Bethel Rd. -

Vintage Whiskey Menu (Pdf)

EACH TASTING IS PRICED PER 1 OZ. POUR CAREFULLY CURATED by FRED MINNICK VINTAGE WHISKEY VINTAGE VINTAGE WHISKEYS FROM 1800’s a TASTE of HISTORY TO MODERN ERA Our unique collection features whiskey, bourbon, and rye brands from across the globe, including over 400 vintage American whiskeys curated by renowned whiskey author Fred Minnick. THE 1800‘S Throughout the 1800s, whiskey dominated the news and medicine. You’d find whiskey invading the White House and causing scandals. President Grant’s reelection campaign was, in part, paid for by whiskey distillers defrauding the government and bribing politicians so they wouldn’t have to pay as much in taxes. It also was the subject of great political debate, from temperance women trying to ban it, to whiskey distillers trying to protect it, while doctors prescribed bourbon for everything from gout to cancer. The whiskeys from this era did not have the same consumer protection as they do today. In some cases, the whiskey rectifiers added acids and unpalatable materials VINTAGE WHISKEY VINTAGE that would be banned by today’s regulations. These whiskeys were tested, but taste at your own risk. IMPORTANT LEGISLATION Bottled in Bond Act of 1897. This was the first consumer protection legislation for whiskey and is still seen on bottles today. E1. CEDAR BROOK WHISKEY VINTAGE HANDMADE SOUR MASH WHISKEY / $1,600 BOTTLED 1892 U.S. President: Benjamin Harrison Cedar Brook was a popular Anderson County brand made at the McBrayer Distillery. This brand won the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. This particular bottle is believed to have been a contract produced product for a grocer named James Levy & Bro. -

“Too Much of Anything Is Bad, but Too Much Good Whiskey Is Barely Enough.”

“Too much of anything is bad, but too much good whiskey is barely enough.” MARK TWAIN PROVISIONS bar snacks & eats lobster roll 23 B+B burger 19 SPICY OLIVES 7 BARREL AGED COCKTAILS Boulevardier 18 rittenhouse rye / cocchi di torino campari Manhattan 18 knob creek rye / dickel rye / cocchi di torino Old Fashioned 18 buffalo trace bourbon / old forester bourbon dickel rye / jameson black barrel demerara simple Sazerac 21 sazerac rye / hennessy vsop demerara simple Samurai 18 bank note scotch / licor 43 amaretto / demerara simple Tipperary 19 jameson black barrel / cocchi di torino green chartreuse page 4 SPECIALTY COCKTAILS Chocolate Volcano 15 tito’s / frangelico / crème de cacao / chocolate cream Campfire Tale 18 highwest campfire bourbon / cruzan blackstrap rum knob creek / cinnamon / sweet potato simple Cross Country 16 rittenhouse rye / amaro montenegro / lemon passion fruit / fresno chili Bengal 16 bols genever / st. george spiced pear liqueur ancho reyes / bengali spice simple / lemon Coconut Lassi 16 tito’s / letherbee absinthe / coconut greek yogurt lime / vanilla simple Whiskey Smash 14 old forester bourbon / lemon / simple / mint St. Honore 16 ron zacapa 23 / auchentoshan scotch / sherry vanilla simple / cream / egg La Mentira 14 sauza tequila / st. george spiced pear liqueur pamplemousse rose / honey simple lime / peppercorn Morning Glory Fizz 16 old forester bourbon / letherbee absinthe / lemon simple / soda / egg white Lake Effect 16 tito’s, prosecco / st. germaine liqueur honey simple / lemon Tai Pan 16 clement rhum agricole / cocchi americano chinese five spice / lime / bitters page 5 BOURBON BARON PROGRAM Regions around the world create unique expressions of what we call whiskey, whisky, scotch whiskey and bourbon, utilizing various grains, barrels and aging techniques to create distinct profile characteristics. -

Too Much of Anything Is Bad, but Too Much Good Whiskey Is Barely Enough.”

“Too much of anything is bad, but too much good whiskey is barely enough.” MARK TWAIN PROVISIONS available at the bar from 2pm - 5pm SPICED NUTS + BACON 8 lobster roll 23 SPICY OLIVES 7 B & B Burger 19 James Beard Week Featured Cocktail The Yankee Clipper 15 “I can’t taste rum without visualizing Yankee clipper ships in full sail, palm-fringed Caribbean inlets inhabited by buccaneers, and dimly lit waterfront taverns of the 18th century where our forebears studied maps of buried treasure and planned how to run the British blockade,” - James Beard CLASSIC COCKTAILS Daiquiri 15 brugal dry rum / lime / sugar MANHATTAN 15 rittenhouse 100 proof rye / carpano antica / aromatic bitters BOULEVARDIER 14 knob creek 100 proof bourbon / campari / carpano antica toronto 14 knob creek rye / fernet / demerara OLD FASHIONED 15 old forester bourbon / demerara / orange and aromatic bitters SAZERAC 15 highwest rendevous rye / absinthe / peychaud’s bitters Spanish COffee (served hot) 25 bacardi 151 / kahlua / metropolis coffee / whipped cream page 4 SPECIALTY COCKTAILS Chocolate Whip 15 housemade hot chocolate / brandy / bourbon / grand marnier Sparkling Skyline 15 beefeater gin / st. germaine / giffard pamplemousse / lime / prosecco Kitihawa 15 belvedere vodka / lemon / grapefruit / st. germaine foam American redhead 15 ginger / lemon / ancho-mint bourbon LSD 15 partida tequila / amaro montenegro / lime / crème de cassis Ravenswood Mule 15 koval bourbon / st. george spiced pear / lemon / ginger beer R&R 15 brugal dry white rum / chareau / lime / mint / -

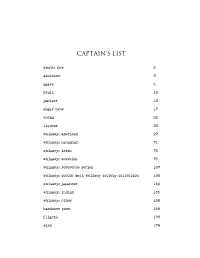

Captain's List

CAPTAIN’S LIST what’s new 2 absinthe 3 agave 5 fruit 10 juniper 13 sugar cane 17 vodka 22 liqueur 23 whiskey: american 27 whiskey: canadian 71 whiskey: irish 72 whiskey: scottish 75 whiskey: reference series 107 whiskey: scotch malt whiskey society collection 108 whiskey: japanese 150 whiskey: indian 155 whiskey: other 156 hardcore porn 159 flights 173 wine 174 WHAT’S NEW D2 old forester statesman 47.5% $14 D2 copperworks single malt release no. 5 50% $14 D2 redemption wheated bourbon 48% $13 D2 distiller’s way 10 yr 47.8% $12 david nicholson 1843 1963 stitzel-weller* $550 E0 angel’s envy cask strength 2016 62.3% $75 G4 old maysville club 50% $24 D0 jack daniel's single barrel barrel proof 65.25% $18 D0 iron smoke apple wood smoked whiskey 40% $16 D0 old forester 1920 prohibition style 57.5% $14 tullamore dew cider cask 40% $11 ardbeg an oa 46.6% $23 imperial 1995 15 yr signatory $21 mortlach 1995 19 yr alexander murray & co 55.6% $41 monumental 30 yr alexander murray & co 40% $51 C3 chateau de pellehaut 1989 28 yr armagnac $43 C4 roger groult calvados pays d’auge reserve 40% $15 B2 foursquare 2015 11 yr zinfandel cask 43% $15 H4 vigilant navy strength 57% $11 B2 el buho especial joven mezcal 48% $28 2 ABSINTHE absinthe amer $19 absinthe bizarre 69% -swiss $33 absinthe bourgeois les fils d’emile pernot $22 absinthe l’ancienne 2012 $51 absinthe l’ancienne 2013 $47 absinthe l’ancienne 2014 $41 absinthe valkyria, oak aged 60% - swedish $41 adnams southwold copper house absinthe verte $27 angelique verte suisse $23 brevens h.r. -

The Poetry and Humor of the Scottish Language

in" :^)\EUN'i\TPr/> ^ c^ < ^ •-TilJD^ =o o ir.t' ( qm-^ I| POETRY AND HUMOUR OF THE SCOTTISH LANGUAGE. THE POETRY AND HUMOUR OF THE SCOTTISH LANGUAGE. BY CHARLES MACKAY, LL.D, " Autlior of The Gaelic Etymology of the Languages of Westerti Europe, tuore particularly of the English and Lowland Scotch;" " Recreations Gauloises, or Sources Celtigues de la " " Langue Fratifaise ; and The Obscure Words and Phrases in Shakspeare and his Con- temporaries" is'c. ALEXANDER GARDNER, PAISLEY; LONDON : 12 PATERNOSTER ROW. 1882. :•: J ^ PREFACE. a I/) c The nucleus of this volume was contributed in three " papers to Blackwood's Magazine," at the end of the year 1869 and beginning of 1870. They are here of Messrs. r--. reprinted, by the kind permission Blackwood, CO ^ with many corrections and great extensions, amounting "^ to more than two-thirds of the volume. The original :> intention of the work was to present to the admirers of ^o Scottish literature, where it differs from that of England, only such words as were more poetical and humorous in the Scottish language than in the English, or were \ altogether wanting in the latter. The design gradually extended itself as the with his ^ compiler proceeded task, ^^11 it came to include large numbers of words derived from the Gaelic or Keltic, with which Dr. Jamieson, the 4 author of the best and most copious Scottish Dictionary ^ hitherto published, was very imperfectly or scarcely at all acquainted, and which he very often wofuUy or ludi- crously misunderstood. " Broad Scotch," says Dr. Adolphus Wagner, the eru- and editor of the Poems of Robert dite sympathetic Burns,— pubUshed in Leipzig, in 1835, "is literally broadened, i.e.^ a language ot dialect very worn off, and blotted, whose VL PREFACE. -

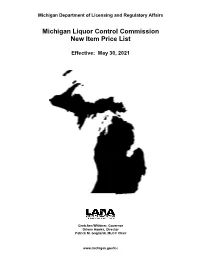

Michigan Liquor Control Commission New Item Price List

Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs Michigan Liquor Control Commission New Item Price List Effective: May 30, 2021 Gretchen Whitmer, Governor Orlene Hawks, Director Patrick M. Gagliardi, MLCC Chair www.michigan.gov/lcc ADA CODE BRAND NAME PROOF SIZE PACK BASE ON OFF MINIMUM NO. # IN ML SIZE PRICE PREMISES PREMISES SHELF PRICE PRICE PRICE NEW ITEMS: MAY 30, 2021 STRAIGHT BOURBON 141 24379 MAMMOTH BT SMALL BATCH BOURBON 86.0 750 12 40.16 35.75 38.16 44.99 141 24307 NORTH PIER CSK STRGTH BBN WSKY 115.7 750 6 57.75 51.40 54.86 64.68 141 24455 SINGLETREE SMALL BATCH BOURBON 89.5 750 12 27.66 24.63 26.29 30.99 STRAIGHT RYE 141 24419 DARBY'S RESERVE RYE WHISKEY 90.0 750 12 24.99 22.24 23.74 27.99 141 24420 DARBY'S RESERVE RYE WHISKEY 90.0 1750 6 45.53 40.52 43.25 50.99 141 24306 NORTH PIER CSK STRGTH RYE WSKY 115.7 750 6 57.75 51.40 54.86 64.68 CANADIAN 141 24450 MCADAMS CANADIAN WHISKEY 80.0 750 12 11.61 10.32 11.02 12.99 141 24451 MCADAMS CANADIAN WHISKEY 80.0 1750 6 21.41 19.07 20.35 23.99 SCOTCH 141 24340 MASH CUT BLENDED SCOTCH WHISKY 86.0 750 6 24.11 21.44 22.89 26.99 MISCELLANEOUS WHISKEY 141 24288 COASTAL CREEK PB WHISKEY 60.0 750 6 24.11 21.44 22.89 26.99 141 24289 THREE CHORD SINGLE BARREL BBN 95.0 750 6 44.62 39.70 42.37 49.96 141 24290 THREE CHORD STRAIGHT WHISKEY 85.0 750 6 26.78 23.83 25.44 29.99 141 24291 THREE CHORD STRAIGHT WHISKEY 85.0 1000 6 31.24 27.80 29.68 34.99 GIN 141 24287 AFTER V PREMIUM AUSTRALIAN GIN 80.0 750 6 33.00 29.37 31.35 36.96 141 24441 HADLEY & SONS GIN 92.0 750 12 15.16 13.50 14.41 16.99 -

The Whiskey Book

THE WHISKEY BOOK THE HOUSE WHISKEY Buffalo Trace If you’re drinking whiskey just for fun, and aren’t interested Frankfort, Kentucky 90 Proof in discerning the subtle differences between the array of Buffalo Trace Bourbon is our House We at Eureka! take great pride in our Bourbon at Eureka! and we take choices available to you, then by all means continue to whiskey selection and we appreciate the great pride in being able to serve this amazing whiskey in our house work that went into crafting it. We take cocktails. Buffalo Trace is renowned drink whatever you’d like. We aren’t going to tell you how equal pride in having such a fine whiskey for making quality products for over 200 Years. Buffalo Trace is one of as our house offering. All of our signature only a few distilleries that was allowed bourbon cocktails are made with verve, to continue to produce whiskey to enjoy yourself. However, we are here to tell you that if during prohibition. Although the care, and this superb whiskey. name of the distillery has changed over the years, one thing has re- discovering new facets and insight about your whiskey mained consistent: their dedication to great American-made whiskey. sounds like enjoyment to you, then enjoyment you shall Nose: sweet caramel, toffee, cereal, and hints of oak and cinnamon Taste: brown sugar, spice, oak, find. We can help you pinpoint your favorite whiskies and toffee, dark fruit, and anise Finish: long and smooth with a to understand what about them you like, so you can find slight hint of toasty oak and mint more favorites.