Nordic American Voices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Battlefields & Treaties

welcome to Indian Country Take a moment, and look up from where you are right now. If you are gazing across the waters of Puget Sound, realize that Indian peoples thrived all along her shoreline in intimate balance with the natural world, long before Europeans arrived here. If Mount Rainier stands in your view, realize that Indian peoples named it “Tahoma,” long before it was “discovered” by white explorers. Every mountain that you see on the horizon, every stand of forest, every lake and river, every desert vista in eastern Washington, all of these beautiful places are part of our Indian heritage, and carry the songs of our ancestors in the wind. As we have always known, all of Washington State is Indian Country. To get a sense of our connection to these lands, you need only to look at a map of Washington. Over 75 rivers, 13 counties, and hundreds of cities and towns all bear traditional Indian names – Seattle, Tacoma, Yakima, and Spokane among them. Indian peoples guided Lewis and Clark to the Pacifi c, and pointed them safely back to the east. Indian trails became Washington’s earliest roads. Wild salmon, delicately grilled and smoked in Alderwood, has become the hallmark of Washington State cuisine. Come visit our lands, and come learn about our cultures and our peoples. Our families continue to be intimately woven into the world around us. As Tribes, we will always fi ght for preservation of our natural resources. As Tribes, we will always hold our elders and our ancestors in respect. As Tribes, we will always protect our treaty rights and sovereignty, because these are rights preserved, at great sacrifi ce, ABOUT ATNI/EDC by our ancestors. -

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation As a National Heritage Area

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION APRIL 2010 The National Maritime Heritage Area feasibility study was guided by the work of a steering committee assembled by the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Steering committee members included: • Dick Thompson (Chair), Principal, Thompson Consulting • Allyson Brooks, Ph.D., Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation • Chris Endresen, Office of Maria Cantwell • Leonard Forsman, Chair, Suquamish Tribe • Chuck Fowler, President, Pacific Northwest Maritime Heritage Council • Senator Karen Fraser, Thurston County • Patricia Lantz, Member, Washington State Heritage Center Trust Board of Trustees • Flo Lentz, King County 4Culture • Jennifer Meisner, Washington Trust for Historic Preservation • Lita Dawn Stanton, Gig Harbor Historic Preservation Coordinator Prepared for the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation by Parametrix Berk & Associates March , 2010 Washington State NATIONAL MARITIME HERITAGE AREA Feasibility Study Preface National Heritage Areas are special places recognized by Congress as having nationally important heritage resources. The request to designate an area as a National Heritage Area is locally initiated, -

Pm AGENCY Office of Education (DREW), Washington, P

itOCUITT RESUME 2-45t 95 . - ,RC 010 425 .. UTROR' Niatuw, Duane; Rickman, Uncle TITLE The. History and Culture of the'Indiand of Wilahington State ---A curriculua'GuiAer..Revised 1975. ,INmpUTION Washington Office of the State Superintendent of .' Public Instruction, Olympia.; Washington Univ., v .1 . 'Seattle. Coll. of Edication. , ;pm AGENCY Office of Education (DREW), Washington, p. C. r 08-,DATE . 75' Lima -------,_ 248p.: - BOBS PRICE HF-$0443-7801.414.71 Plus POstage. " -DESCRIPTORS Activities; fAmericarLindians; Audioviival lids; *Bibliographies; Cat:mad-inn-Concept Formation; Conflict; *Cultural Awareness; CuTttialBackground. Cultural Differences; *CurriCulumOuideal-iducat4onal Objectives; *Elementary 'Secondary- Education;. Enrichment; Futures (of Society) * 'History; Instructional Materials: InterdiLiplOau Approach:. / Organizations (Groups); Problems; *Reionice ., Haterfals; Social Change; Students; Teachers IDENTIF*S' *Washington -,,,. 'AB4T4CT - 0 social. Designed to be utilized as a supplementtar,,, studies crr culum (any level) .in-the public schodlgirofAiasking,ton thiscurricula*,- guide on: the histOry 4AWc4tt#4 of . ..- 4t4te. ... NAshington's American Indians includes; ailindez; a 0.14-00-;#04ia . , guide;-a guide to teaching materialetsauath0-2, .., resource ._..., -_,,,......- -, ,study,itself. The content of the course of St04200#441'6 ;:thee .: 11#10 4;eisearlii life of the Indians ofilvall#00,01*4,the::,. NMshington Indians! encounter with non 4andiane;,04-0400,0 ,,, .InAians of Washington. The subject patter iso.0#4110kiii*OePt P ' A4'n'Of'Socialissuesand is developedbysielliWWCO:i01041. '. ,,,f ,4ener4imationS, and values derived from all at 00,:4140(science dirge 04Ines;specific objectives and actAvitieg:4Sik 4414- c -60d. e:)14.1liggraphy/resources section inclu400: 40040, l is: ,; mt. ipii; gases: newspapers and journ4s1 twOotdM, MOta 'Wit organizations and institutions; U.S. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NFS Form 10-900-b 0MB No, 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Movie Theaters in Washington State from 1900 to 1948 B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Film Entertainment in Washington from 1900 to 1948________________________ (Historic Contexts for future development) ____________________________ Stage, Musical, and Oratory Entertainment in Washington from Early Settlement to 1915 Entertainment Entrepreneurs in Washington from 1850 to 1948 C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ The State of Washington LjSee continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the NationaLRegister documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFfe ParM6t) and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. / 6* /JL^ , , , /^ \ MA^D L *'Jr *^^ August 20, 1991 Signature of certifying official Date Waphingpon State Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Statelor Federal agency and bureau ^ 1, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

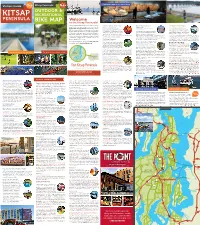

VKP Visitorguide-24X27-Side1.Pdf

FREE FREE MAP Kitsap Peninsula MAP DESTINATIONS & ATTRACTIONS Visitors Guide INSIDE INSIDE Enjoy a variety of activities and attractions like a tour of the Suquamish Museum, located near the Chief Seattle grave site, that tell the story of local Native Americans Welcome and their contribution to the region’s history and culture. to the Kitsap Peninsula! The beautiful Kitsap Peninsula is located directly across Gardens, Galleries & Museums Naval & Military History Getting Around the Region from Seattle offering visitors easy access to the www.VisitKitsap.com/gardens & Memorials www.VisitKitsap.com/transportation Natural Side of Puget Sound. Hop aboard a famous www.VisitKitsap.com/arts-and-culture visitkitsap.com/military-historic-sites- www.VisitKitsap.com/plan-your-event www.VisitKitsap.com/international-visitors WA State Ferry or travel across the impressive Tacaoma Visitors will find many places and events that veterans-memorials The Kitsap Peninsula is conveniently located Narrows Bridge and in minutes you will be enjoying miles offer insights about the region’s rich and diverse There are many historic sites, memorials and directly across from Seattle and Tacoma and a short of shoreline, wide-open spaces and fresh air. Explore history, culture, arts and love of the natural museums that pay respect to Kitsap’s remarkable distance from the Seattle-Tacoma International waterfront communities lined with shops, art galleries, environment. You’ll find a few locations listed in Naval, military and maritime history. Some sites the City & Community section in this guide and many more choices date back to the Spanish-American War. Others honor fallen soldiers Airport. One of the most scenic ways to travel to the Kitsap Peninsula eateries and attractions. -

Youth Vax Clinic Release

Contact: Sarah van Gelder For the Suquamish Tribe [email protected] 206-491-0196 OR Ginger Vaughan For the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe [email protected] 360-620-9107 Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe and Suquamish Tribe Host Youth Vaccination Clinic on May 17 All Tribal youth or any youth living in North Kitsap aged 12 to 17 now eligible to receive Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine The Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe and the Suquamish Tribe are partnering to host a COVID-19 Youth Vaccination Clinic on Monday, May 17 from 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. at the Elders Center on the PGST government campus. Tribal youth or any youth living in North Kitsap aged 12 – 17 are invited to get vaccinated at the clinic. An appointment is required and can be scheduled online at https://bookpgst.timetap.com. Vaccinations are provided free of charge. There are 300 appointments available at this clinic. Participants will receive their first dose of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine. A second follow-up shot will be provided three weeks later. All participants will be expected to return to the same location for their second dose on June 7. Parental consent is required for anyone under the age of 18. Parents or legal guardians can accompany their child to the appointment or provide a signed consent form along with a phone number should they need to be reached. Consent forms are available for download after setting up an appointment. The Pfizer vaccine was recently approved by the FDA, CDC, and Washington State Health Department for youth as young as 12 years old. -

Indigenous Walking Tour at the University of Washington Dedicated to Indigenous Students; Past, Present, and Future

Indigenous Walking Tour at the University of Washington Dedicated to Indigenous students; past, present, and future. First Edition: 2021 Written by Owen L. Oliver Illustrations by Elijah N. Pasco (@the_campus_sketcher) This piece of work was written, created, and curated within multiple Indigenous lands and waters. Not limited to but including the Musqueam, Duwamish, Suquamish, Tulalip, Muckleshoot, Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian territories Contents Stop 1: Guest from the Great River Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture The beginning of this tour starts with a testament of knowledge. Specifically, Indigenous knowledge systems, Stop 2: Longhouse Welcome and how they are grounded in place on the University of Washington campus. This is especially important as these Intellectual House systems are not sprinkled around like many visitors and guests to the land may view it. These knowledge systems Stop 3: A Changing Story are rooted in the natural landscape that ties language Miller Hall and sacred history into what we call ‘Place’. Place of the first peoples has been intentionally and continuously Stop 4: Shoreline Connection entangled with colonial assimilation and destruction. What few people explain though, is how resilient Union Bay Natural Area and Preserve these Indigenous Knowledge Systems are. Ultimately, forgetting to showcase how these Indigenous Stop 5: Rest and Relaxation communities alongside welcomed community members, University of Washington Medicinal Garden allies, and all peoples take action and responsibility to prune out historical disenfranchisements. Stop 6: Building Coalitions, Inspiring others Samuel E. Kelly Ethnic Cultural Center Stop 7: Onward Husky Union Building Stop 1: Guests from the Great River I come from the people of the Lower Columbia River. -

Meeting and Weaving with Your 100 Grandparents

Cover of new book by Ed Carriere, Suquamish Elder and Master Basketmaker and Dale Croes, Wet Site Archaeologist, Washington State University. (Left, back cover) Ed’s Archaeology Basket representing ancient weaves from 4,500, 3,000, 2,000 and 1,000 years ago in the Salish Sea, (Right, cover) Dale and Ed with their replicated 2,000 year old Biderbost wet site pack baskets (Carriere and Croes 2018; available on Amazon.com). Meeting and Weaving with your 100th Grandparents Ed Carriere, Suquamish Elder (84) and Master Basketweaver and Canoe Carver, and Dale R. Croes, Washington State University (WSU) wet/waterlogged archaeological site and ancient basket specialist (71), have written a book documenting their partnership in understanding and replicating the over 2,000 years, or 100 generations, of ancient Salish Sea basketry artifacts. This article takes excerpts from this new book in Ed’s own words as he contributes half the text in this 300 page book, accompanied with details by 314 color plates, 100 line drawings, maps and charts, bibliography, list of suggested readings, a glossary and full index. The book, Re- Awakening Ancient Salish Sea Basketry, Fifty Years of Basketry Studies is published by Northwest Anthropology, LLC. and available through Amazon.com. Search for Carriere and click on his Author’s page for a great video featuring him making his traditional clam baskets that he had made for his family (Figure 1). 1 Figure 1. Ed Carriere, Suquamish Elder and Master Basketmaker and Dale Croes, Ph.D., WSU Wet site archaeologist in front of replicated Biderbost and other baskets they made and use to explain a new approach they are proposing that involves both ongoing cultural transmission and archaeological analysis: Generationally-Linked Archaeology. -

THE SUQUAMISH TRIBE October 27,2011 PO Box 498 Suquamish, WA 98392-0498

PHorur (360) 598-3311 Fax (360) 598-6295 ish.nsn.us THE SUQUAMISH TRIBE October 27,2011 PO Box 498 Suquamish, WA 98392-0498 Keri Weaver City of Poulsbo Planning Department 200 NE Moe Street Poulsbo, WA 98370 Re: Poulsbo Shoreline Master Program Update (File 09-21-l l-1) The proposed project area lies within the Suquamish Tribe's ancestral territory and Usual and Accustomed fishing area ("U&A"). The 1855 Treaty of Point Elliot outlined articles of agreement between the United States and the Suquamish Tribe. Under the articles of the treaty the Tribe ceded certain areas of its aboriginal lands to the United States and reserved for its use and occupation certain lands, rights and privileges and the United States assumed fiduciary obligations, including, but not limited to, legal and fiscal responsibilities to the Tribe. Aboriginal rights reserved under the Treaty includes the immemorial custom and practice to hunt, fish, and gather within the usual and accustomed grounds and stations, which was the basis of the Tribe's source of food and culture. Treaty-reserved resources situated on and offthe Port Madison Indian Reservation include, but are not limited to, fishery resources situated within the Suquamish Tribe's U&A which extend well beyond Reservation boundaries and crosses at least five counties in Puget Sound. Ethnographic and archaeological evidence demonstrates that the Suquamish people have lived, gathered food stuffs, produced ceremonial and spiritual items, and hunted and fished for thousands of years in the area now known as Kitsap County (Barbara Lane, Identity, Treaty Status and Fisheries of the Suquamish Tribe of the Port Madison Indian Reservation,1974). -

Federal Register/Vol. 72, No. 95/Thursday, May 17, 2007/Notices

27846 Federal Register / Vol. 72, No. 95 / Thursday, May 17, 2007 / Notices represent the physical remains of nine This notice is published as part of the between the Native American human individuals of Native American National Park Service’s administrative remains and the Confederated Tribes of ancestry. Officials of the Museum of responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 the Umatilla Reservation, Oregon. Anthropology, Washington State U.S.C. 3003 (d)(3). The determinations Representatives of any other Indian University also have determined that, in this notice are the sole responsibility tribe that believes itself to be culturally pursuant to 25 U.S.C. 3001 (3)(A), the 82 of the museum, institution, or Federal affiliated with the human remains objects described above are reasonably agency that has control of the Native should contact Dr. John Finney, believed to have been placed with or American human remains. The National Associate Dean, University of Puget near individual human remains at the Park Service is not responsible for the Sound, 1500 N. Warner, Tacoma, WA time of death or later as part of the death determinations in this notice. 98416, telephone (253) 879–3207, before rite or ceremony. Lastly, officials of the A detailed assessment of the human June 18, 2007. Repatriation of the Museum of Anthropology, Washington remains was made by the Slater human remains to the Confederated State University have determined that, Museum of Natural History, University Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, pursuant to 25 U.S.C. 3001 (2), there is of Puget Sound professional staff and a Oregon may proceed after that date if no a relationship of shared group identity consultant in consultation with additional claimants come forward. -

Testimony of Leonard Forsman

TESTIMONY OF LEONARD FORSMAN CHAIRMAN SUQUAMISH TRIBE BEFORE THE SENATE COMMITTEE OF INDIAN AFFAIRS DOUBLING DOWN ON INDIAN GAMING: EXAMINING NEW ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR SUCCESS IN THE NEXT 30 YEARS” OCTOBER 4, 2017 Good afternoon Chairman Hoeven, Vice Chairman Udall, and Members of the Committee. Thank you for the opportunity to testify at this important hearing. My name is Leonard Forsman and I serve as the chairman of the Suquamish Tribe located in Washington state. The Suquamish Tribe is a signatory to the Treaty of Point Elliot of 1855 and a federally recognized Indian tribe. The Tribe has roughly 950 enrolled citizens, half of whom reside on the Tribe’s present day homeland on the Point Madison Indian Reservation, which is located just west of Seattle, WA, across Puget Sound. I am here today to testify about how tribal governmental gaming is working. For the Suquamish Tribe, gaming has helped to revitalize our government, and enable us to invest in the Suquamish people and our future. Our tribe still faces many challenges, but governmental gaming has brought greater tribal employment, education, economic development, and reacquisition of our reservation lands. As one of the largest employers in our region, government gaming has also given the Suquamish Tribe a seat at the table with our neighboring jurisdictions and governments to discuss shared interests and issues impacting our communities. Tribal Background The name Suquamish means “people of the clear saltwater.” We are the successor to the Suquamish and Duwamish people. Chief Seattle signed the Treaty of Point Elliot in 1855, on behalf of the Suquamish and Duwamish—34 years before Washington became the 42nd state. -

History & Culture Chief Seattle Page 1 of 3 the Suquamish Tribe: People

The Suquamish Tribe: People of Chief Seattle - History & Culture Page 1 of 3 Search... Login Home History & Culture Employment Departments Museum Suquamish Foundation Contact Community Notices You Are Here: History & Culture Monday, August 1, 2016 History & Culture The Suquamish are a Lushootseed (Puget Salish) speaking people that traditionally lived along the Kitsap Chief Seattle Peninsula, including Bainbridge and Blake Islands, across Puget Sound from present Seattle. Many of the present Suquamish live on the Port Madison Indian Reservation in the reservation towns of Suquamish and Indianola. The ancestral Suquamish have lived in Central Puget Sound for approximately 10,000 years. The major Suquamish winter village was at Old Man House on the shoreline of Agate Passage at d’suq’wub meaning “clear salt water.” The Suquamish name translates into the “people of the clear salt water.” The Suquamish depended on salmon, cod and Chief Seattle other bottom fish, clams and other shellfish, berries, roots, ducks and other waterfowl, deer and other land game for was an food for family use, ceremonial feasts, and for trade. The Suquamish, due to the absence of a major river with large ancestral leader salmon runs in their immediate territory, had to travel to neighboring marine areas and beyond to harvest salmon. of the Suquamish The Suquamish Tribe born in lived in shed- 1786 at the roofed, cedar Old-Man-House plank houses village in Suquamish. His father was during the winter Schweabe, a Suquamish Chief, and his months. The was mother Scholitza, a Duwamish Suquamish had from a village near present Kent. winter villages at Seattle was a six years old when Suquamish (Old- Captain George Vancouver anchored in Man-House), Point Suquamish waters off Bainbridge Bolin, Poulsbo, Silverdale, Chico, Colby, Olalla, Point White, Lynwood Center, Eagle Harbor, Port Madison and Battle Island in 1792.