Comparison of Physicochemical Methods to Remove Arsenic from Landfill Leachate and Gas Condensate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playing Chicken: Avoiding Arsenic in Your Meat Around the World Through Research and Education, Science and Technology, and Advocacy

Playing Chicken Avoiding Arsenic in Your Meat Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy Food and Health Program The Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy About this publication promotes resilient family farms, rural communities and ecosystems Playing Chicken: Avoiding Arsenic in Your Meat around the world through research and education, science and technology, and advocacy. Written by David Wallinga, M.D. 2105 First Avenue South We would like to thank Ted Schettler, M.D., Minneapolis, Minnesota 55404 USA Karen Florini and Mardi Mellon for their helpful comments Tel.: (612) 870-0453 on this manuscript. We would especially like to acknowledge Fax: (612) 870-4846 the major contributions of Alise Cappel. We would like [email protected] iatp.org to thank the Quixote Foundation for their support of this work. iatp.org/foodandhealth Published April 2006 © 2006 IATP. All rights reserved. Table of contents Executive summary . 5 I. The modern American chicken: Arsenic use in context . 11 II. Concerns with adding arsenic routinely to chicken feed . 14 II. What we found: Arsenic in chicken meat . 21 Appendix A. FDA-approved feed additives containing arsenic . 26 Appendix B. Testing methodology . 29 References . 31 Playing Chicken: Avoiding Arsenic in Your Meat 3 4 Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy Executive summary Arsenic causes cancer even at the low levels currently feed additive, are given each year to chickens. Arsenic found in our environment. Arsenic also contributes to other is an element—it doesn’t degrade or disappear. Arsenic diseases, including heart disease, diabetes and declines subsequently contaminates much of the 26-55 billion pounds in intellectual function, the evidence suggests. -

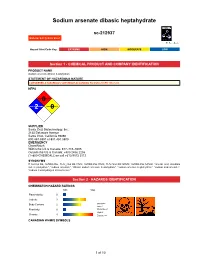

Sodium Arsenate Dibasic Heptahydrate

Sodium arsenate dibasic heptahydrate sc-212937 Material Safety Data Sheet Hazard Alert Code Key: EXTREME HIGH MODERATE LOW Section 1 - CHEMICAL PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION PRODUCT NAME Sodium arsenate dibasic heptahydrate STATEMENT OF HAZARDOUS NATURE CONSIDERED A HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE ACCORDING TO OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1200. NFPA FLAMMABILITY0 HEALTH2 HAZARD INSTABILITY0 SUPPLIER Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. 2145 Delaware Avenue Santa Cruz, California 95060 800.457.3801 or 831.457.3800 EMERGENCY ChemWatch Within the US & Canada: 877–715–9305 Outside the US & Canada: +800 2436 2255 (1–800-CHEMCALL) or call +613 9573 3112 SYNONYMS H-As-Na2-O4, AsHO4.2Na, H-As_Na2-O4.7H2O, AsHO4.2Na.7H2O, H-As-Na2-O4.12H2O, AsHO4.2Na.12H2O, "arsenic acid, disodium salt, heptahydrate", "sodium arseniate", "dibasic sodium arsenate heptahydrate", "sodium arsenate heptahydrate", "sodium acid arsenate", "sodium monohydrogen orthoarsenate" Section 2 - HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION CHEMWATCH HAZARD RATINGS Min Max Flammability: 0 Toxicity: 3 Body Contact: 2 Min/Nil=0 Low=1 Reactivity: 0 Moderate=2 High=3 Chronic: 4 Extreme=4 CANADIAN WHMIS SYMBOLS 1 of 10 EMERGENCY OVERVIEW RISK May cause CANCER. Toxic by inhalation and if swallowed. Very toxic to aquatic organisms, may cause long-term adverse effects in the aquatic environment. POTENTIAL HEALTH EFFECTS ACUTE HEALTH EFFECTS SWALLOWED ! Toxic effects may result from the accidental ingestion of the material; animal experiments indicate that ingestion of less than 40 gram may be fatal or may produce serious damage to the health of the individual. ! Ingestion may produce nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, bloody stools, shock, rapid pulse and coma. Severe gastritis or gastroenteritis may occur as a result of lesions produced by vascular damage from absorbed arsenic (and not local corrosion); symptoms may be delayed for several hours. -

Multi-Residue Determination of Organic Arsenical Drugs in Feeds by LC-MS/MS

Multi-Residue Determination of Organic Arsenical Drugs in Feeds by LC-MS/MS Geneviève Grenier, Melanie Titley & Lise-Anne Prescott AAFCO Laboratory Methods and Services Committee meeting 2016-01-18 Background • Animal Feed Division of CFIA identified a high priority need for the determination of three organic arsenicals (arsanilic acid, roxarsone and nitarsone) at residue levels in animal feed • These are withdrawal drugs and are priority food contaminants • Current test methods are at guarantee levels greater than 10% minimum use rate • Therefore, current methods not well suited for residue or traceback testing • Requested feed residue LOQ of 1 mg/kg for all three organic arsenicals 2 Background • UHPLC-PDA Challenges • Extract were very dirty • Tried sample clean-up using Oasis MAX SPE • Still very dirty • HPLC Challenges • Compounds elute too easily • Analytical column must : retain and separate compounds, and give good peak shape • Analytical column : Phenomenex Onyx Monolithic C18 100 X 3.0mm 3 Background • LC/MS/MS method (positive mode) • Column: Phenomenex Onyx Monolithic C18 100 X 3.0mm • Linearity problems with Internal Standard (IS) • Internal standard – 4-hydroxyphenylarsonic acid • Peak area of the internal standard increased with increasing analyte concentration • Cause • 4-hydroxyphenyl arsanic acid co-elute with Arsanilic acid and have similar m/z 4 New method - summary • Liquid chromatography combined with atomic and molecular mass spectrometry for speciation of arsenic in chicken liver. Peng et. al., Journal of Chromatography -

Inorganic Arsenic Compounds Other Than Arsine Health and Safety Guide

OS INTERNATiONAL I'ROGRAMME ON CHEMICAL SAFETY Health and Safety Guide No. 70 INORGANIC ARSENIC COMPOUNDS OTHER THAN ARSINE HEALTH AND SAFETY GUIDE i - I 04 R. Q) UNEP UNITED NATIONS INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENT I'R( )GRAMME LABOUR ORGANISATION k\s' I V WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION, GENEVA 1992 IPcs Other H EA LTH AND SAFETY GUIDES available: Aerytonitrile 41. Clii rdeon 2. Kekvau 42. Vatiadiuni 3 . I Bula not 43 Di meLhyI ftirmatnide 4 2-Buta101 44 1-Dryliniot 5. 2.4- Diehlorpheiioxv- 45 . Ac rylzi mule acetic Acid (2.4-D) 46. Barium 6. NIcihylene Chhride 47. Airaziiie 7 . ie,i-Buia nol 48. Benlm'.ie 8. Ep Ichioroli) Olin 49. Cap a 64 P. ls.ihutaiiol 50. Captaii I o. feiddin oeth N lene Si. Parai.tuat II. Tetradi ion 51 Diquat 12. Te nacelle 53. Alpha- and Betal-lexachloro- 13 Clils,i (lane cyclohexanes 14 1 kpia Idor 54. Liiidaiic IS. Propylene oxide 55. 1 .2-Diciilroetiiane Ethylene Oxide 5t. Hydrazine Eiulosiillaii 57. F-orivaldehydc IS. Die h lorvos 55. MLhyI Isobu I V I kcloiic IV. Pculaehloro1heiiol 59. fl-Flexaric 20. Diiiiethoaie 61), Endrin 2 1 . A iii in and Dick) 0in 6 I . I sh IIZiLI1 22. Cyperniellirin 62. Nicki. Nickel Caution I. and some 23. Quiiiloieiic Nickel Compounds 24. Alkthrins 03. Hexachlorocyclopeuladiene 25. Rsiiiethii ins 64. Aidicaib 26. Pyr rot ii,id inc Alkaloids 65. Fe nitrolhioit 27. Magnetic Fields hib. Triclilorlon 28. Phosphine 67. Acroleiii 29. Diiiiethyl Sull'ite 68. Polychlurinated hiphenyls (PCBs) and 30. Dc lianteth nil polyc h In ruiated letlilienyls (fs) 31. -

Pharmaceutical Residues in the Environment • Jolanta Kumirska Pharmaceutical Residues in the Environment

Pharmaceutical Residues in the Environment the in Residues Pharmaceutical • Jolanta Kumirska Jolanta • Pharmaceutical Residues in the Environment Edited by Jolanta Kumirska Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Molecules www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Pharmaceutical Residues in the Environment Pharmaceutical Residues in the Environment Editor Jolanta Kumirska MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Jolanta Kumirska University of Gdansk, Faculty of Chemistry, Department of Environmental Analysis Poland Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Molecules (ISSN 1420-3049) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules/special issues/pharmaceutical residues environment). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03943-485-5 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03943-486-2 (PDF) c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Jolanta Kumirska Special Issue “Pharmaceutical Residues in the Environment” Reprinted from: Molecules 2020, 25, 2941, doi:10.3390/molecules25122941 ............. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0304998 A1 Sem (43) Pub

US 20100304998A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/0304998 A1 Sem (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 2, 2010 (54) CHEMICAL PROTEOMIC ASSAY FOR Related U.S. Application Data OPTIMIZING DRUG BINDING TO TARGET (60) Provisional application No. 61/217,585, filed on Jun. PROTEINS 2, 2009. (75) Inventor: Daniel S. Sem, New Berlin, WI Publication Classification (US) (51) Int. C. GOIN 33/545 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: GOIN 27/26 (2006.01) ANDRUS, SCEALES, STARKE & SAWALL, LLP C40B 30/04 (2006.01) 100 EAST WISCONSINAVENUE, SUITE 1100 (52) U.S. Cl. ............... 506/9: 436/531; 204/456; 435/7.1 MILWAUKEE, WI 53202 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY, Disclosed herein are methods related to drug development. Milwaukee, WI (US) The methods typically include steps whereby an existing drug is modified to obtain a derivative form or whereby an analog (21) Appl. No.: 12/792,398 of an existing drug is identified in order to obtain a new therapeutic agent that preferably has a higher efficacy and (22) Filed: Jun. 2, 2010 fewer side effects than the existing drug. Patent Application Publication Dec. 2, 2010 Sheet 1 of 22 US 2010/0304998 A1 augavpop, Patent Application Publication Dec. 2, 2010 Sheet 2 of 22 US 2010/0304998 A1 g Patent Application Publication Dec. 2, 2010 Sheet 3 of 22 US 2010/0304998 A1 Patent Application Publication Dec. 2, 2010 Sheet 4 of 22 US 2010/0304998 A1 tg & Patent Application Publication Dec. 2, 2010 Sheet 5 of 22 US 2010/0304998 A1 Patent Application Publication Dec. -

Arsenical Timeline Final Proofed

Backgrounder: FDA and Pfizer’s Collusion to Downplay Effects of Arsenicals in the U.S. Chicken Supply This document summarizes the FDA’s actions after learning that inorganic arsenic, a human carcinogen, was potentially present in the U.S. chicken supply and the FDA’s eventual decision to conduct its own study. It then discusses FDA’s relationship with Pfizer throughout this process and after the study results were made available. It details how the extremely close working relationship led to considerable collusion between the FDA and Pfizer in delaying the public release of the FDA’s study and in creating a coordinated media strategy, which included Pfizer supplying the actual content of the FDA’s media statements in order to minimize the impact of the announcement. The FDA has approved arsenical drugs for use in chickens, turkeys and pigs. These drugs have been approved for multiple purposes, including growth promotion, improved pigmentation and to treat, control and prevent animal diseases, such as coccidiosis, a parasitic infection of the intestinal track in poultry that can lead to death.1 The FDA has recognized organic arsenic as safe, while inorganic arsenic is considered a carcinogen. Chronic exposure to inorganic arsenic may lead to the development of lung, bladder or skin cancer, and is also associated with 1 Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Questions and Answers Regarding 3-Nitro (Roxarsone) (2011). Available at http://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/SafetyHealth/ProductSafetyInformation/ucm2583 13.htm. cardiovascular disease.2 Inorganic arsenic exposure may also lead to diabetes, neurological problems in children and adverse pregnancy outcomes.3 Because there are a variety of sources of inorganic arsenic in food (including rice and apple juice), the FDA attempts to monitor these sources.4 Alpharma Inc. -

Risk Assessment Report Arsenic in Foods (Chemicals and Contaminants)

[Tentative translation] Risk Assessment Report Arsenic in foods (Chemicals and Contaminants) Food Safety Commission Japan (FSCJ) October 2013 0 [Tentative translation] Contents Page Chronology of Discussions .................................................................................................... 3 List of members of the Food Safety Commission .................................................................. 3 List of members of the EPCC, the Food Safety Commission ................................................ 4 Executive summary ................................................................................................................ 6 I. Background ......................................................................................................................... 9 II. Outline of the Substances under Assessment .................................................................... 9 1. Physiochemical properties ......................................................................................... 9 (1) Metallic arsenic ................................................................................................... 9 (2) Inorganic arsenic compounds ........................................................................... 10 (3) Organic arsenic compounds .............................................................................. 12 (4) Analytical methods for arsenic ......................................................................... 16 2. Major use and production ....................................................................................... -

Interagency Committee on Chemical Management

DECEMBER 15, 2020 INTERAGENCY COMMITTEE ON CHEMICAL MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 02-19 REPORT TO THE GOVERNOR WALKE, PETER Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 II. Chemical Nomination Review Framework .......................................................................... 6 III. Summary of Chemical Use in the State Based on Reported Chemical Inventories.......... 8 IV. Summary of Identified Risks to Human Health and the Environment from Reported Chemical Inventories .............................................................................................................. 9 V. Summary of any change under Federal Statute or Rule affecting the Regulation of Chemicals in the State ............................................................................................................ 9 VI. Recommended Legislative or Regulatory Action to Reduce Risks to Human Health and the Environment from Regulated and Unregulated Chemicals of Emerging Concern . 25 VII. Final Thoughts ................................................................................................................. 26 Appendices ................................................................................................................................... 27 1 Executive Summary On August 7, 2017, Governor -

Interagency Committee on Chemical Management

DECEMBER 14, 2018 INTERAGENCY COMMITTEE ON CHEMICAL MANAGEMENT EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 13-17 REPORT TO THE GOVERNOR WALKE, PETER Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 I. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 3 II. Recommended Statutory Amendments or Regulatory Changes to Existing Recordkeeping and Reporting Requirements that are Required to Facilitate Assessment of Risks to Human Health and the Environment Posed by Chemical Use in the State ............................................................................................................................ 5 III. Summary of Chemical Use in the State Based on Reported Chemical Inventories....... 8 IV. Summary of Identified Risks to Human Health and the Environment from Reported Chemical Inventories ........................................................................................................... 9 V. Summary of any change under Federal Statute or Rule affecting the Regulation of Chemicals in the State ....................................................................................................... 12 VI. Recommended Legislative or Regulatory Action to Reduce Risks to Human Health and the Environment from Regulated and Unregulated Chemicals of Emerging Concern .............................................................................................................................. -

INVESTIGATION of a NOVEL APPROACH for ARSENIC REMOVAL from WATER USING MODIFIED RHYOLITE by VINOTH MANOHARAN Bachelor of Technol

INVESTIGATION OF A NOVEL APPROACH FOR ARSENIC REMOVAL FROM WATER USING MODIFIED RHYOLITE By VINOTH MANOHARAN Bachelor of Technology Perriyar University Tamilnadu, India 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December, 2005 INVESTIGATION OF A NOVEL APPROACH FOR ARSENIC REMOVAL FROM WATER USING MODIFIED RHYOLITE Thesis Approved: Dr. John N. Veenstra Thesis Advisor Dr. Gregory G. Wilber Dr. Steve Cross Dr. A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I extend my sincere gratitude and appreciation to many people who made this masters thesis possible. Special thanks are due to Dr. John N. Veenstra, my principal advisor for guidance and encouragement throughout my research work. I would like to express my sincere thanks to Dr. Steve Cross, a member of my advisory committee for his effort and support. I would like to extent my words of appreciation to Dr. Grergory G. Wilber for his help in troubleshooting of the lab equipments and his immediate presence whenever needed. Many thanks are due to the lab manager Mr. David Porter for helping me out in setting up experiments. I would also like to thank my friends Muralikrishnana Erat and Ann Mary Mathew for their constructive suggestions and the moral support they had offered. I am also thankful to Indumathi Appan, Arthi Krubanandh and Kirubhakaran Vyravan for their help at different stages of the research work. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 11 Overview......................................................................................................................... 1 Project Objective............................................................................................................. 2 ARSENIC BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... -

1 Study 318.41 Executive Summary Organic-Based Arsenical

Study 318.41 Executive Summary Organic-based arsenical compounds have been used in chickens since March 21, 1944, when the drug 3-Nitro® was approved. The active ingredient in 3-Nitro® is a chemical called roxarsone. Roxarsone and other organic arsenicals (nitarsone, arsanilic acid, and carbarsone) were approved for use in chickens for growth promotion, feed efficiency and improved pigmentation. The organic arsenicals, especially roxarsone, were approved in combination with other drugs such as narasin or salinomycin to prevent coccidiosis, a parasitic disease infecting the intestinal tracts in chickens which can lead to death. When 3-Nitro® (roxarsone) and the other organic arsenicals were approved, it was assumed that only organic arsenic and not inorganic arsenic would be excreted from the chickens. Organic arsenic compounds are much less toxic than inorganic arsenic, which is a known human carcinogen. Inorganic arsenic exists in two forms, arsenic (III) and arsenic (V) (pronounced arsenic-3, or trivalent arsenic, and arsenic 5, or pentavalent arsenic, respectively). The number refers to the number of electrons that elemental arsenic can donate to form other compounds. Humans (and other animals) can convert arsenic (V) to arsenic (III), which increases arsenic’s toxicity and retention by the body. In response to scientific reports that organic arsenicals could be transformed by the body into inorganic arsenic, scientists in FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine, in collaboration with scientists from FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition undertook a study to address this question; can an approved organic arsenical (3-Nitro®; roxarsone) when incorporated into chicken feed and fed to chickens according to approved label directions, result in the presence of inorganic arsenic in edible tissues? Using state-of-the art technology, FDA scientists were able to develop and validate a new analytical method that had the necessary sensitivity and specificity to detect and quantify the low levels of inorganic arsenic that were expected to be in edible tissues.