Countering Violent Extremism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nairobi Attack and Al-Shabab's Media Strategy

OCTOBER 2013 . VOL 6 . ISSUE 10 Contents The Nairobi Attack and FEATURE ARTICLE 1 The Nairobi Attack and Al-Shabab’s Al-Shabab’s Media Strategy Media Strategy By Christopher Anzalone By Christopher Anzalone REPORTS 6 The Dutch Foreign Fighter Contingent in Syria By Samar Batrawi 10 Jordanian Jihadists Active in Syria By Suha Philip Ma’ayeh 13 The Islamic Movement and Iranian Intelligence Activities in Nigeria By Jacob Zenn 19 Kirkuk’s Multidimensional Security Crisis By Derek Henry Flood 22 The Battle for Syria’s Al-Hasakah Province By Nicholas A. Heras 25 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts Kenyan soldiers take positions outside the Westgate Mall in Nairobi on September 21, 2013. - Photo by Jeff Angote/Getty Images fter carrying out a bold Godane. The attack also followed a attack inside the upscale year in which al-Shabab lost control Westgate Mall in Nairobi in of significant amounts of territory in September 2013, the Somali Somalia, most importantly major urban Amilitant group al-Shabab succeeded in and economic centers such as the cities recapturing the media spotlight. This of Baidoa and Kismayo. was in large part due to the nature of the attack, its duration, the difficulty This article examines al-Shabab’s About the CTC Sentinel in resecuring the mall, the number of media strategy during and immediately The Combating Terrorism Center is an casualties, and al-Shabab’s aggressive after the Westgate Mall attack, both independent educational and research media campaign during and immediately via micro-blogging on Twitter through institution based in the Department of Social after the attack.1 its various accounts as well as more Sciences at the United States Military Academy, traditional media formats such as West Point. -

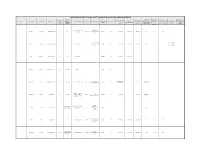

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11/01-12/31/14 Date of Initial Terrorist Country or If Parents Are Defendant's Immigration Status If a U.S. Citizen, Entry or Immigration Status Current Organization Conviction Current Territory of Origin, Citizens, Natural- Number Charge Date Conviction Date Defendant Age at Conviction Offenses Sentence Date Sentence Imposed Last U.S. Residence at Time of Natural-Born or Admission to at Time of Initial Immigration Status Affiliation or District Immigration Status If Not a Natural- Born or Conviction Conviction Naturalized? U.S., If Entry or Admission of Parents Inspiration Born U.S. Citizen Naturalized? Applicable 243 months 18/2339B; 18/922(g)(1); 1 5/27/2014 10/30/2014 Donald Ray Morgan 44 ISIS 5/13/15 imprisonment; 3 years MDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Natural-Born N/A N/A N/A 18/924(a)(2) SR 3 years imprisonment; Unknown. Mother 2 8/29/2013 10/28/2014 Robel Kidane Phillipos 19 2x 18/1001(a)(2) 6/5/15 3 years SR; $25,000 DMA MA U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Naturalized Ethiopia came as a refugee fine from Ethiopia. 3 4/1/2014 10/16/2014 Akba Jihad Jordan 22 ISIS 18/2339A EDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen 4 9/24/2014 10/3/2014 Mahdi Hussein Furreh 31 Al-Shabaab 18/1001 DMN MN 25 years Lawful Permanent 5 11/28/2012 9/25/2014 Ralph Kenneth Deleon 26 Al-Qaeda 18/2339A; 18/956; 18/1117 2/23/15 CDCA CA N/A Philippines imprisonment; life SR Resident 18/2339A; 18/2339B; 25 years 6 12/12/2012 9/25/2014 Sohiel Kabir 37 Al-Qaeda 18/371 (1812339D 2/23/15 CDCA CA U.S. -

Isis in the West

NEW INTERNATIONAL AMERICA SECURITY PETER BERGEN, COURTNEY SCHUSTER, AND DAVID STERMAN ISIS IN THE WEST THE NEW FACES OF EXTREMISM NOVEMBER 2015 About New America About the International Security Program New America is dedicated to the renewal of American The International Security Program aims to provide politics, prosperity, and purpose in the Digital Age. We evidence-based analysis of some of the thorniest carry out our mission as a nonprofit civic enterprise: an questions facing American policymakers and the public. intellectual venture capital fund, think tank, technology The program is largely focused on South Asia and the laboratory, public forum, and media platform. Our Middle East, al-Qaeda and allied groups, the rise of hallmarks are big ideas, impartial analysis, pragmatic political Islam, the proliferation of weapons of mass policy solutions, technological innovation, next destruction (WMD), homeland security, and the activities generation politics, and creative engagement with broad of U.S. Special Forces and the CIA. The program is also audiences. Find out more at newamerica.org/our-story. examining how warfare is changing because of emerging technologies, such as drones, cyber threats, and space- based weaponry, and asking how the nature and global About The Authors spread of these technologies is likely to change the very definition of what war is. Peter Bergen is a print, television and web journalist, documentary producer and the The authors would like to thank Emily Schneider and author or editor of six books, three of which Justin Lynch for their assistance with this research. were New York Times bestsellers and three of which were named among the best non- fiction books of the year by The Washington Post. -

American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat

American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat /name redacted/ Specialist in Organized Crime and Terrorism February 19, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R41416 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat Summary This report describes homegrown violent jihadists and the plots and attacks that have occurred since 9/11. For this report, “homegrown” describes terrorist activity or plots perpetrated within the United States or abroad by American citizens, lawful permanent residents, or visitors radicalized largely within the United States. The term “jihadist” describes radicalized individuals using Islam as an ideological and/or religious justification for their belief in the establishment of a global caliphate, or jurisdiction governed by a Muslim civil and religious leader known as a caliph. The term “violent jihadist” characterizes jihadists who have made the jump to illegally supporting, plotting, or directly engaging in violent terrorist activity. The report also discusses the radicalization process and the forces driving violent extremist activity. It analyzes post-9/11 domestic jihadist terrorism and describes law enforcement and intelligence efforts to combat terrorism and the challenges associated with those efforts. Appendix A provides details about each of the post-9/11 homegrown jihadist terrorist plots and attacks. There is an “executive summary” at the beginning that summarizes the report’s findings. Congressional -

When Jihadis Come Marching Home: the Terrorist Threat Posed by Westerners Returning from Syria and Iraq

Perspective C O R P O R A T I O N Expert insights on a timely policy issue When Jihadis Come Marching Home The Terrorist Threat Posed by Westerners Returning from Syria and Iraq Brian Michael Jenkins lthough the numbers of Western fighters slipping off to total number. U.S. intelligence sources indicate that 100 or more join the jihadist fronts in Syria and Iraq are murky, U.S. Americans have been identified. In an interview on October 5, counterterrorism officials believe that those fighters pose 2014, Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey said a clear and present danger to American security. Some that the FBI knew the identities of “a dozen or so” Americans who Awill be killed in the fighting, some will choose to remain in the were fighting in Syria on the side of the terrorists (Comey, 2014). Middle East, but some will return, more radicalized, determined to His comment surprised many who were familiar with the intel- continue their violent campaigns at home. Their presence in Syria ligence reports, but he was probably referring to a narrowly defined and Iraq also increases the available reservoir of Western passports category of persons who at the time of his statement were known and “clean skins” that terrorist planners could recruit to carry out to be currently fighting with particular terrorist groups in Syria. If terrorist missions against the West. we include all of those who went to or tried to go to Syria or Iraq How many Americans have gone to Syria? It is estimated to join various rebel formations, some of whom were arrested upon that as many as 15,000 foreigners have gone to Syria and Iraq to departure, some of whom were killed in the fighting, and some of fight against the Syrian or Iraqi governments, including more than whom have returned, the larger number would apply. -

Ohio Terrorism Potential Male American Terrorists Case Studies Terror Recruit? Terrorists Definitions of Terrorism

Americans Killing Americans: A Comparison of U.S. Male Citizens Charged with Acts Related to Terrorism Since 9/11. Terry Oroszi, MS, EdD Boonshoft School of Medicine, WSU Henry Jackson Foundation, WPAFB The Dayton Think Tank, Dayton, OH Plan of Action… Are You a Research on Ohio Terrorism Potential Male American Terrorists Case Studies Terror Recruit? Terrorists Definitions of Terrorism International Terrorism Domestic Terrorism Terrorism “use or threatened use of “violent acts that are “the intent to instill fear, and violence to intimidate a dangerous to human life the goals of the terrorists population or government and and violate federal or state are political, religious, or thereby effect political, laws” ideological” religious, or ideological change” Demographic patterns of enlisted terrorist recruits. Females Convicted with Acts Related to Terrorism Amera Akl, Angel Shannon, Kathy Aubsworth, Brandi Bowman, Joanne Chesimard, Shannon Conley, Kristi Goldstein, Carole Gordon, Sedina Hodzic, October Laris, Colleen LaRose, Tashfeen Malik, Nicole Mansfield, Proscovia Nzabanita, Diana Oughton, Jamie Ramirez, Nadia Rockwood, Shelly Shannon, Asia Siddiqui, Susan Stern, Lynne Stewart, Zeinab Taleb-Jedi, Noelle Velentzas, Jaelyn Young 1. If you are female please sit down. “Women are soft, gentle, and innocent” Sjoberg, L., & Gentry, C. E. (Eds.). (2011). Women, gender, and terrorism. University of Georgia Press. 2. If you are younger than 17, or older than 33 sit down. Oots, K. L. (1989). Organizational perspectives on the formation and disintegration of terrorist groups. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 12(3), 139-152. Hughbank, R. J., & Hughbank, D. L. (2008). The application of the social learning theory to domestic terrorist recruitment. SWATdigest. -

ISIS in the WEST the Western Militant Flow to Syria and Iraq

PETER BERGEN, DAVID STERMAN, ALYSSA SIMS, AND ALBERT FORD ISIS IN THE WEST The Western Militant Flow to Syria and Iraq UPDATED MARCH 2016 About the Authors About New America Peter Bergen is a print, television and New America is committed to renewing American politics, web journalist, documentary producer prosperity, and purpose in the Digital Age. We generate big and the author or editor of seven books, ideas, bridge the gap between technology and policy, and three of which were New York Times curate broad public conversation. We combine the best of bestsellers and three of which were a policy research institute, technology laboratory, public named among the best non-fiction books of the year by forum, media platform, and a venture capital fund for The Washington Post. The books have been translated into ideas. We are a distinctive community of thinkers, writers, twenty languages. Documentaries based on his books researchers, technologists, and community activists who have been nominated for two Emmys and also won the believe deeply in the possibility of American renewal. Emmy for best documentary in 2013. Find out more at newamerica.org/our-story. Mr. Bergen is vice president of New America, and directs the organization’s International Security and Fellows programs. He is CNN’s national security analyst, a About the International Security Program Professor of Practice at Arizona State University and a fellow at Fordham University’s Center on National Security. The International Security Program aims to provide evidence-based analysis of some of the thorniest David Sterman is a senior program questions facing American policymakers and the public. -

CTC Sentinel 6(4)

APRIL 2013 . VOL 6 . ISSUE 4 Contents Hizb Allah Resurrected: FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Hizb Allah Resurrected: The Party of The Party of God’s Return to God’s Return to Tradecraft By Matthew Levitt Tradecraft REPORTS By Matthew Levitt 6 The Sinaloa Federation’s International Presence By Samuel Logan 10 Boko Haram: Reversals and Retrenchment By David Cook 13 The Salafist Temptation: The Radicalization of Tunisia’s Post- Revolution Youth By Anne Wolf 16 Rethinking Counterinsurgency in Somalia By William Reno 19 France: A New Hard Line on Kidnappings? By Anne Giudicelli 22 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 24 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts Lebanese Hizb Allah militants visit the grave of former military chief Imad Mughniyyeh. - Anwar Amro/AFP/Getty Images uring the past few years, This article traces Hizb Allah’s recent Lebanese Hizb Allah’s spike in operational activity since global operations increased 2008, highlighting the group’s efforts markedly, but until recently to rejuvenate the capabilities of its IJO. Dits efforts yielded few successes. In July Many of these details derive from the 2012, however, Hizb Allah operatives author’s extensive conversations with bombed a busload of Israeli tourists in Israeli security officials in Tel Aviv, Burgas, Bulgaria, killing five Israelis which were then vetted and confirmed About the CTC Sentinel and a Bulgarian bus driver.1 Yet what in conversations with American and The Combating Terrorism Center is an may prove no less significant than this European security, intelligence and independent educational and research operational success was another plot military officials. institution based in the Department of Social foiled in Cyprus just two weeks earlier. -

PERSPECTIVES on TERRORISM Volume 9, Issue 6 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editor 1 I

ISSN 2334-3745 Volume IX, Issue 6 December 2015 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 9, Issue 6 Table of Contents Welcome from the Editor 1 I. Articles The Evolution of Al Qaeda’s Global Network and Al Qaeda Core’s Position Within it: A Network Analysis 2 by Victoria Barber Radical Groups’ Social Pressure Towards Defectors: The Case of Right-Wing Extremist Groups 36 by Daniel Koehler Religion, Democracy and Terrorism 51 by Nilay Saiya 20 Years Later: A Look Back at the Unabomber Manifesto 60 by Brett A. Barnett II. Research Notes Re-Examining the Involvement of Converts in Islamist Terrorism: A Comparison of the U.S. and U.K. 72 by Sam Mullins Terrorist Practices: Sketching a New Research Agenda 85 by Joel Day Eyewitness Accounts from Recent Defectors from Islamic State: Why They Joined, What They Saw, Why They Quit 95 by Anne Speckhard and Ahmet S. Yayla III. Resources Bibliography: Homegrown Terrorism and Radicalisation 119 Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes IV. Book Reviews Counterterrorism Bookshelf: 40 Books on Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism-Related Subjects 154 Reviewed by Joshua Sinai ISSN 2334-3745 i December 2015 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 9, Issue 6 V. Notes from the Editor A Word of Appreciation for Our External Peer Reviewers 167 from the Editorial Team TRI Award for Best PhD Thesis 2015: Call for Submissions 169 TRI National/Regional TRI Networks (Partial) Inventory of Ph.D. Theses in the Making 170 by Alex P. Schmid (Network Coordinator) Job Announcement: Open Rank Faculty Search at CTSS, UMass Lowell 175 About Perspectives on Terrorism 177 ISSN 2334-3745 ii December 2015 PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 9, Issue 6 Welcome from the Editor Dear Reader, We are pleased to announce the release of Volume IX, Issue 6 (December 2015) of Perspectives on Terrorism at www.terrorismanalysts.com. -

Foreign Fighters Under International Law

ACADEMY BRIEFING No. 7 Foreign Fighters under International Law October 2014 Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Geneva Académie de droit international humanitaire et de droits humains à Genève Academ The Academy, a joint centre of ISBN: 978-2-9700866-6-6 © Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, October 2014. Acknowledgements This Academy Briefing was researched and written by Sandra Kraehenmann, Research Fellow at the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights (Geneva Academy). The Geneva Academy would like to thank all those who commented on a draft of the Briefing, in particular Ambassador Stephan Husy, Swiss Coordinator for International Counter-Terrorism; Professor Andrea Bianchi, Professor of International Law, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies; Pascal-Hervé Bogdañski, Senior Legal Adviser, Counterterrorism, Coordination Office, Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (DFAE); and Emilie Max, Legal Officer, Directorate of International Law, DFAE. The Geneva Academy would also like to thank the DFAE for its support to the Academy’s research on foreign fighters under international law. Editing, design, and layout by Plain Sense, Geneva. Disclaimer This Academy Briefing is the work of the author. The views expressed in it do not necessarily reflect those of the project’s supporters or of anyone who provided input to, or commented on, a draft of this Briefing. The designation of states or territories does not imply any judgement by the Geneva Academy or DFAE regarding the legal status of such states or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or the delimitation of their boundaries, or the status of any states or territories that border them. -

Foreign Fighter Involvement in Syria

FOREIGN FIGHTER INVOLVEMENT IN SYRIA Ms. J. Skidmore Research Assistant, ICT January 2014 ABSTRACT As the conflict in Syria approaches its third year, increasing attention and concern are being paid to the conflict’s extremely high number of foreign fighters (FFs). Conservative estimates place the number of FFs in Syria between 6,000 – 12,000. Thus, Syria has attracted more FFs than any other previous conflict, and in particular, has attracted an enormous number of Western FFs. FFs pose various threats to both their home states and the current conflict. The staggering numbers of FFs in Syria therefore, have alarmed security officials who are faced with these threats. By outlining these various threats, assessing the Syrian conflict and its key actors, and the various FFs involved, this report seeks to explain why Syria has attracted so many FFs. Furthermore, this report proposes several essential measures necessary for counter strategies, specifically those developed by Western states. * The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT). 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 5 Why a Threat? ................................................................................................................. 7 LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................................................ -

United States District Court Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

AO 91 (REV.5/85) Criminal Complaint AUSA William E. Ridgway (312) 469-6233 W44444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CRIMINAL COMPLAINT v. CASE NUMBER: ABDELLA AHMAD TOUNISI I, the undersigned complainant, being duly sworn on oath, state that the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief: On or about April 19, 2013, in the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division, and elsewhere, ABDELLA AHMAD TOUNISI, defendant herein: knowingly attempted to provide material support and resources, namely, personnel, to a foreign terrorist organization, namely, al-Qaida in Iraq, designated as a foreign terrorist organization by the United States Department of State on or about October 15, 2004, and amended to include the alias Jabhat al-Nusrah on or about December 11, 2012, knowing that the organization was a designated terrorist organization and that the organization had engaged and was engaging in terrorist activity and terrorism, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 2339B(a)(1). I further state that I am a Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and that this complaint is based on the facts contained in the Affidavit which is attached hereto and incorporated herein. Signature of Complainant Dwayne W. Golomb Special Agent, Federal Bureau of Investigation Sworn to before me and subscribed in my presence, April 20, 2013 Chicago, Illinois at City and State Date DANIEL G. MARTIN, U.S. Magistrate Judge Name & Title of Judicial Officer Signature of Judicial Officer UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT ) ) NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS ) AFFIDAVIT Introduction and Agent Background I, Dwayne W.