Redalyc.Film and Ritual. Epistemological Dialogs Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grandmothers Matter

Grandmothers Matter: Some surprisingly controversial theories of human longevity Introduction Moses Carr >> Sound of rolling tongue Wanda Carey >> laughs Mariel: Welcome to Distillations, I’m Mariel Carr. Rigo: And I’m Rigo Hernandez. Mariel: And we’re your producers! We’re usually on the other side of the microphones. Rigo: But this episode got personal for us. Wanda >> Baby, baby, baby… Mariel: That’s my mother-in-law Wanda and my one-year-old son Moses. Wanda moved to Philadelphia from North Carolina for ten months this past year so she could take care of Moses while my husband and I were at work. Rigo: And my mom has been taking care of my niece and nephew in San Diego for 14 years. She lives with my sister and her kids. Mariel: We’ve heard of a lot of arrangements like the ones our families have: grandma retires and takes care of the grandkids. Rigo: And it turns out that across cultures and throughout the world scenes like these are taking place. Mariel: And it’s not a recent phenomenon either. It goes back a really long time. In fact, grandmothers might be the key to human evolution! Rigo: Meaning they’re the ones that gave us our long lifespans, and made us the unique creatures that we are. Wanda >> I’m gonna get you! That’s right! Mariel: A one-year-old human is basically helpless. We’re special like that. Moses can’t feed or dress himself and he’s only just starting to walk. Gravity has just become a thing for him. -

Patterns of Traumatic Injury in Historic African and African American Populations

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2005 Patterns of Traumatic Injury in Historic African and African American Populations Christina Nicole Brooks University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Brooks, Christina Nicole, "Patterns of Traumatic Injury in Historic African and African American Populations. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1801 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Christina Nicole Brooks entitled "Patterns of Traumatic Injury in Historic African and African American Populations." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Murray K Marks, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Andrew Kramer, George White Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Christina Nicole Benton Brooks entitled “Patterns of Traumatic Injury in Historic African and African American Populations.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. -

Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation Through Kinship Terminology Erin Wilkinson

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Mexico University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Linguistics ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2009 Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation through Kinship Terminology Erin Wilkinson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds Recommended Citation Wilkinson, Erin. "Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation through Kinship Terminology." (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds/40 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TYPOLOGY OF SIGNED LANGUAGES: DIFFERENTIATION THROUGH KINSHIP TERMINOLOGY BY ERIN LAINE WILKINSON B.A., Language Studies, Wellesley College, 1999 M.A., Linguistics, Gallaudet University, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Linguistics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico August, 2009 ©2009, Erin Laine Wilkinson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii DEDICATION To my mother iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many thanks to Barbara Pennacchi for kick starting me on my dissertation by giving me a room at her house, cooking me dinner, and making Italian coffee in Rome during November 2007. Your endless support, patience, and thoughtful discussions are gratefully taken into my heart, and I truly appreciate what you have done for me. I heartily acknowledge Dr. William Croft, my advisor, for continuing to encourage me through the long number of months writing and rewriting these chapters. -

Gender, Language, and Wills Karen J

Marquette Law Review Volume 98 Article 3 Issue 4 Summer 2015 Not Your Mother's Will: Gender, Language, and Wills Karen J. Sneddon Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Repository Citation Karen J. Sneddon, Not Your Mother's Will: Gender, Language, and Wills, 98 Marq. L. Rev. 1535 (2015). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol98/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW Volume 98 Summer 2015 Number 4 NOT YOUR MOTHER’S WILL: GENDER, LANGUAGE, AND WILLS KAREN J. SNEDDON* “Boys will be boys, but girls must be young ladies” is an echoing patriarchal refrain from the past. Formal equality has not produced equality in all areas, as demonstrated by the continuing wage gap. Gender bias lingers and can be identified in language. This Article focuses on Wills, one of the oldest forms of legal documents, to explore the intersection of gender and language. With conceptual antecedents in pre-history, written Wills found in Ancient Egyptian tombs embody the core characteristics of modern Wills. The past endows the drafting and implementation of Wills with a wealth of traditions and experiences. The past, however, also entombs patriarchal notions inappropriate in Wills of today. This Article explores the language of the Will to parse the historical choices that remain relevant choices for today and the vestiges of a patriarchal past that should be avoided. -

The Dobe Ju/'Hoansi

Lee Case Studies Janice E. Stockard and From the Field to the Classroom Dobe Ju/’hoansi The in Cultural Anthropology George Spindler, Series Editors Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology Series Editors: Janice E. Stockard and George Spindler The Dobe Ju/’hoansi Fourth Edition Geographically and topically diverse, the Case The Dobe Ju/’hoansi, 4th Edition, Studies in Cultural Anthropology series has Richard B. Lee Richard B. Lee enriched the study of cultural anthropology ISBN-13: 978-1-111-82877-6 and the social sciences for countless Shadowed Lives: Undocumented Immigrants in undergraduate and graduate students. More American Society than 200 ethnographies have been published , 3rd Edition, Leo R. Chavez through the years, many of which have ISBN-13: 978-1-133-58845-0 become classics in the field. And as the world continues to evolve into a global community, CourseReader for Cultural Anthropology the more recent studies in the series provide CourseReader: Cultural Anthropology allows not only readable, informative ethnographic you to create a fully customized online treatments of the world’s cultures but also reader in minutes. Access a rich collection discussions of their interactions and the of thousands of primary and secondary consequent changes that ensue. sources, readings, and audio and video selections from multiple disciplines. You A partial listing of series titles follows. For have the freedom to assign and customize more information on the series and to access individualized content at an affordable price. a wide range of anthropology resources, CourseReader: Cultural Anthropology is the visit us on the web at www.cengage.com/ perfect complement to any class. -

Language and Culture. Work Papers of SIL-AAB, Series B, Volume 8. INSTITUTION Summer Inst

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 282 426 FL 016 724 AUTHOR Hargrave, Susanne, Ed. TITLE Language and Culture. Work Papers of SIL-AAB, Series B, Volume 8. INSTITUTION Summer Inst. of Linguistics, Darwin (Australia). Australian Aborigines Branch. REPORT NO ISBN-0-86892-252-8 PUB DATE Dec 82 NOTE 242p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020)-- Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Children; Color; Comparative Analysis; Concept Formation; Creoles; *Cultural Context; Cultural Traits; Ethnic Groups; Females; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Kinship; Language Research; Lexicology; Linguistic Theory; Literacy; *Mathematical Concepts; Social Values; Sociocultural Patterns; Structural Analysis (Linguistics); Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *Aboriginal People; Anindilyakwa; *Australia;Yanyuwa Possessives ABSTRACT Six Papers on the relationship of language and culture in the Australian Aboriginal contextare presented. "Some Thoughts on Yanyuwa Language and Culture" byJean Kirton gives an overview of some language-culture relationships and examinesseven kinds of possession in one language. "Nyangumarta Kinship:A Woman's Viewpoint" by Helen Geytenbeck outlines kinship and itsterminology as learned by a field linguist for her work with thisgroup. In "A Description of the Mathematical Concepts of Groote Hylandt Aborigines," Judith Stokes describesan Anindilyakwa mathematical language in its cultural context, refuting popular-generalizations about the limited counting ability of the Aboriginal people."Facts and Fallacies of Aboriginal Number Systems" by John Harriscriticizes anthropologists' and linguists' neglect of and bias concerning existing data about the mathematics of Aboriginalgroups. In "Aboriginal Mathematical Concepts: A Cultural and Linguistic Explanation for Some of the Problems," BarbaraSayers suggests that the mathematical problems of some Aboriginal schoolchildrenare real, but have a cultural rather than linguistic basis. -

Hav and Paula

Hav’s Family Paula and our nephew, Max Our hom! Hav and Paula Dear Birth Mother, Thank you for taking the time to read our profile. We have wanted to be parents for a long time but have been unable to have a child. You are considering one of the biggest decisions in your life. We are humbled by your dedication to giving your child a good home. We respect and admire your courage. We’d like to tell you about our lives so that you might have the information you need to consider our family. Thank you. ! 1 We’ve shaped our work lives so that the child we are blessed to adopt will be cared for at home by us. Paula currently is a hospital nurse, and she works only on the weekends; therefore she is home full-time during the week. Hav works in education, focusing on ‘on-line’ education, much of which she can do from home. Your child would be blessed to have both parents at home most of the time. As Hav also speaks Spanish, we hope to give our child the opportunity to learn more than one language. The opportunity for a very warm and stable home and a great education are part of what we want to share. Paula, with our nephew, Max, and niece, Thierry We have been very blessed to share the last 22 years together as life partners and best friends. We met in college after we, literally, bumped into each other in a stair well. After nearly falling down the staircase, we got up, brushed ourselves off and ended up laughing for two hours about our mishap as we shared our life stories with each other. -

Stacey & Larry's Story

Stacey and Larry We are blessed in so many ways, and most importantly having been raised by very loving families that gave us both a strong moral compass. We’ve always loved children and are excited about adopting! We look forward to providing the same opportunity for a loving, happy, and successful life that we were given. We especially enjoy our new home, with plenty of room to expand our family. It has a beautiful yard that is perfect for kicking a ball or playing tag, and a great driveway just waiting for a game of hopscotch! At playground with niece Caroline & nephew Spencer We live a short walk from a playground/park, and are 15 minutes from a huge amusement and water park. We are both kids at heart and we’re confident that we will be great parents; we’re so excited to start our family through adoption! Teacup ride with niece Caroline & nephew Spencer About Larry, by Stacey I was instantly drawn to Larry’s energy and positive attitude. He’s confident, caring, and is the most generous person I know. He has a great sense of humor, and his friends and I depend on his sound reasoning and great advice. All of these traits would make him a great father, and someone that a child would look up to and could depend on. He is a unique combination of silly and serious. He has the strongest morals of anyone I’ve ever met, and inspires trust and honesty. At the same time, he can make up goofy, adlib lyrics to any song on the radio, and turn any tense situation around by knowing just the right thing to say. -

Children and Young People in Kinship Care

Report #1 Family Links: Kinship Care and Family Contact Research Series Breaking the rules Children and young people in kinship care speak about contact with their families Authors Meredith Kiraly is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne and is currently undertaking a short-term contract at the Offi ce of the Child Safety Commissioner, Victoria. She has a long history of practice in out of home care. Cathy Humphreys is Professor of Social Work at the University of Melbourne. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the young people who participated in this study and were prepared to discuss parts of their lives that often involved considerable pain. Many people assisted with recruiting young people for this study. Cathy Carnovale and Caitlin Telford at the CREATE Foundation arranged and participated in two focus groups. Jo Francis (Mirabel Foundation), Anne McLeish (Grandparents Victoria), Bronwyn Harrison (Oz Child), Robyn Brooke (Offi ce of the Child Safety Commissioner), Joan Healey and many kinship carers from support groups run by the Mirabel Foundation and Grandparents Victoria also helped recruit young people. Jim Oommen (Offi ce of the Child Safety Commissioner) assisted in focus groups. We also thank the members of the Family Links Research Project Reference Group for support and guidance. The Department of Human Services (Children, Youth and Families) provided substantial staff time and fi nancial assistance. The Ross Trust donated funds for project costs. Disclaimer The opinions, comments and/or analysis expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Child Safety Commissioner, and cannot be taken in any way as expressions of Government policy. -

John and Mark

John and Mark ACF Adoptions 1-800-348-0467 www.adoptionflorida.org Hello, We are John and Mark Going to see a race, fun in the sun! Visiting Denmark to meet John’s family We appreciate you taking the time to learn about us. We want you to know how deeply we respect you and the brave choices you are making. It must be an unimaginably complicated decision for you and we are so grateful that you would consider us as a family to support and love your child. We know that you are putting your child’s needs first and how serious and important of a choice you are making. We hope to support you through your journey and share who we are with you. How we met Mark’s niece and nephew arrive! Our family grows! We were both from the same area but didn’t know each other until Mark moved back to be near his family. Before we decided to go on our first date we talked for a while, chatting about our interests, hobbies, and families. The longer we spoke, the clearer it became that we needed to give a relationship a try. The first time we met for a date we brought each other food that we had been cooking for the holidays. We had been talking about how we each enjoyed cooking and when we decided to meet for a date we had the same idea – surprise the other with something special from home. From there, we both knew that we wanted the same things from life – a wonderful home to share with family, many celebrations with friends, and one love and life to share together. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Interrogating Pope Francis: On Gender Theory and Ideological Colonization Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6743q3gx Author Dempsey, Danielle Publication Date 2020 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Interrogating Pope Francis: On Gender Theory and Ideological Colonization A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies by Danielle Marie Dempsey June 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Melissa M. Wilcox, Chairperson Dr. Paul Chang Dr. Molly McGarry The Dissertation of Danielle Marie Dempsey is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my parents, sister, brother-in-law, and my niece and nephew Jackie and A.C. for your unconditional love and support and for being understanding of all the time I had to miss for school, when I would have preferred to be hanging out with you. Aunt Patti, Uncle Marv, and Aunt Lori, you have supported my educational endeavors for as long as I can remember – I think I was ten when I first told you I wanted a PhD, and you have encouraged me ever since. To my cousins Michelle, Megan, and Sadie, and to my Godmother Aunt Pami and the rest of my family, thank you for your love and encouragement now and always. Ms. Paige, you taught me everything I needed to know about life in kindergarten. Mr. Kammer, Ms. -

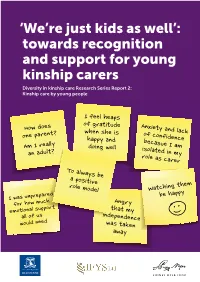

'We're Just Kids As Well': Towards Recognition and Support for Young

‘We’re just kids as well’: towards recognition and support for young kinship carers Diversity in kinship care Research Series Report 2: Kinship care by young people I feel heaps of gratitude Anxiety and lack How does when she is one parent? of confidence happy and becasue I am Am I really doing well isolated in my an adult? role as carer To always be a positive role model Watching them be happy I was unprepared Angry for how much that my emotional support all of us independence would need was taken away ‘We’re just kids as well’: towards recognition and support for young kinship carers Diversity in kinship care Research Series Report 2: Kinship care by young people Writer and Researcher Meredith Kiraly, Honorary Research Fellow Department of Social Work, University of Melbourne Acknowledgements First and foremost I thank the 42 young kinship carers and 16 young people who contributed their time and experiences in the cause of achieving recognition for young kinship carers. I am grateful to David Roth and Cathy Ashley of the UK Family Rights Group and Emeritus Professor Elaine Farmer, Professor Julie Selwyn and Dinithi Wijedasa at the Bristol University School for Policy Studies for consultation about this project in relation to their research about sibling carers. I also acknowledge Dr Lucy Peake of Grandparents Plus UK in relation to our mutual efforts to see effective support extended to younger kinship carers. This project would not have been possible without generous financial support. The R E Ross Trust provided seed funding which was followed by a major grant from the Sidney Myer Fund.