Ema: the New Face of Jane Austen in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastmont High School Items

TO: Board of Directors FROM: Garn Christensen, Superintendent SUBJECT: Requests for Surplus DATE: June 7, 2021 CATEGORY ☐Informational ☐Discussion Only ☐Discussion & Action ☒Action BACKGROUND INFORMATION AND ADMINISTRATIVE CONSIDERATION Staff from the following buildings have curriculum, furniture, or equipment lists and the Executive Directors have reviewed and approved this as surplus: 1. Cascade Elementary items. 2. Grant Elementary items. 3. Kenroy Elementary items. 4. Lee Elementary items. 5. Rock Island Elementary items. 6. Clovis Point Intermediate School items. 7. Sterling Intermediate School items. 8. Eastmont Junior High School items. 9. Eastmont High School items. 10. Eastmont District Office items. Grant Elementary School Library, Kenroy Elementary School Library, and Lee Elementary School Library staff request the attached lists of library books be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Sterling Intermediate School Library staff request the attached list of old social studies textbooks be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont Junior High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books and textbooks for both EJHS and Clovis Point Intermediate School be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. Eastmont High School Library staff request the attached lists of library books for both EHS and elementary schools be declared as surplus. These lists will be posted separately on the website. ATTACHMENTS FISCAL IMPACT ☒None ☒Revenue, if sold RECOMMENDATION The administration recommends the Board authorize said property as surplus. Eastmont Junior High School Eastmont School District #206 905 8th St. NE • East Wenatchee, WA 98802 • Telephone (509)884-6665 Amy Dorey, Principal Bob Celebrezze, Assistant Principal Holly Cornehl, Asst. -

When Fear Is Substituted for Reason: European and Western Government Policies Regarding National Security 1789-1919

WHEN FEAR IS SUBSTITUTED FOR REASON: EUROPEAN AND WESTERN GOVERNMENT POLICIES REGARDING NATIONAL SECURITY 1789-1919 Norma Lisa Flores A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Mark Simon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Brooks Dr. Geoff Howes Dr. Michael Jakobson © 2012 Norma Lisa Flores All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Although the twentieth century is perceived as the era of international wars and revolutions, the basis of these proceedings are actually rooted in the events of the nineteenth century. When anything that challenged the authority of the state – concepts based on enlightenment, immigration, or socialism – were deemed to be a threat to the status quo and immediately eliminated by way of legal restrictions. Once the façade of the Old World was completely severed following the Great War, nations in Europe and throughout the West started to revive various nineteenth century laws in an attempt to suppress the outbreak of radicalism that preceded the 1919 revolutions. What this dissertation offers is an extended understanding of how nineteenth century government policies toward radicalism fostered an environment of increased national security during Germany’s 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the 1919/1920 Palmer Raids in the United States. Using the French Revolution as a starting point, this study allows the reader the opportunity to put events like the 1848 revolutions, the rise of the First and Second Internationals, political fallouts, nineteenth century imperialism, nativism, Social Darwinism, and movements for self-government into a broader historical context. -

Thomas A. Bass on Fukushima Emma Larkin Revisits the Thammasat

Thomas A. Bass on Fukushima MAY–JULY 2020 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 3 Emma Larkin revisits the Thammasat massacre Peter Yeoh profiles Jeremy Tiang Alicia Izharuddin rails against Malaysian food VOLUME 5, NUMBER 3 MAY–JULY 2020 THAILAND 3 Emma Larkin Moments of Silence: The Unforgetting of the October 6, 1976, Massacre in Bangkok, by Thongchai Winichakul POEMS 5 Anthony Tao Coronavirus CHINA 6 Richard Heydarian Democracy in China: The Coming Crisis, by Jiwei Ci HONG KONG 7 David Parrish Unfree Speech: The Threat to Global Democracy and Why We Must Act, by Joshua Wong (with Jason Y. Ng) TAIWAN 8 Michael Reilly The Trouble with Taiwan: History, the United States and a Rising China, by Kerry Brown and Kalley Wu Tzu Hui INDIA 9 Somak Ghosal The Deoliwallahs: The True Story of the 1962 Chinese-Indian Internment, by Joy Ma And Dilip D’souza NOTEBOOK 10 Peter Guest Isolated JAPAN 11 Thomas A. Bass Made in Japan CAMBODIA 19 Prumsodun Ok An Illustrated History of Cambodia, by Philip Coggan MALAYSIA 20 Carl Vadivella Belle Towards a New Malaysia? The 2018 Election and Its Aftermath, by Meredith L. Weiss And Faisal S. Hazis (editors); The Defeat of Barisan: Missed Signs or Late Surge?, by Francis E. Hutchinson and Lee Hwok Aun (editors) SINGAPORE 21 Simon Vincent Hard at Work: Life in Singapore, by Gerard Sasges and Ng Shi Wen SOUTH KOREA 22 Peter Tasker Samsung Rising: The Inside Story of the South Korean Giant That Set Out to Beat Apple and Conquer Tech, by Geoffrey Cain MEMOIR 23 Martin Stuart-Fox Impermanence: An Anthropologist of Thailand and Asia, by -

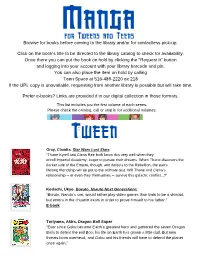

Manga for Tweens and Teens Browse for Books Before Coming to the Library And/Or for Contactless Pick-Up

Manga for Tweens and Teens Browse for books before coming to the library and/or for contactless pick-up. Click on the book's title to be directed to the library catalog to check for availability. Once there you can put the book on hold by clicking the "Request It" button and logging into your account with your library barcode and pin. You can also place the item on hold by calling Teen Space at 516-489-2220 ex 218 If the UPL copy is unavailable, requesting from another library is possible but will take time. Prefer e-books? Links are provided if in our digital collection in those formats. This list includes just the first volume of each series. Please check the catalog, call or stop in for additional volumes. Tween Gray, Claudia. Star Wars Lost Stars “Thane Kyrell and Ciena Ree both know this very well when they enroll Imperial Academy, eager to pursue their dreams. When Thane discovers the darker side of the Empire, though, and defects to the Rebellion, the pair's lifelong friendship will be put to the ultimate test. Will Thane and Ciena's relationship -- or even they themselves -- survive this galactic conflict...?” Kodachi, Ukyo. Boruto, Naruto Next Generations “Boruto, Naruto's son, would rather play video games than train to be a shinobi, but enters in the chuunin exam in order to prove himself to his father.” E-book Toriyama, Akira. Dragon Ball Super “Ever since Goku became Earth’s greatest hero and gathered the seven Dragon Balls to defeat the evil Boo, his life on Earth has grown a little dull. -

Graphic Novel Series

August 2019 Title Bib # Publisher .Hack 17006296 .Hack//g.u.+ 1889995x 0/6 21707212 07-ghost 2342980x 11th cat 10683483 A devil and her love song 22127732 A.I. I love you 21707200 Adolf 10294211 Adventure time : original series 24307713 Adventures of Tintin : 3 in 1 11411879 Afterschool charisma 24182783 Age of bronz 17159775 Akira 20503891 Kodansha Comics Akira 15493519 Dark Horse Alice 19th 10680214 Alice in the country of clover 24154635 Tokyopop Alice in the country of hearts 20531321 Tokyopop amazing Spider-Man 16124364 amazing Spider-Man : world-wide 24571969 American vampire 24399267 Amulet 2019433x ancient magus' bride 24483916 Andel diary 16941949 Angel catbird 25080556 Anonymous noise 25308440 Arata 24110814 Ariol 23898604 Arisa 21280265 Assassination classroom 24335125 Astonishing X-Men 10698887 Astonishing X-Men 2576200x Astro boy 19459919 Attack on Titan 22986819 Attack on Titan before the fall 24295942 Attack on Titan Junior High 23218071 Attack on Titan no regrets 24015970 Avengers K. Avengers vs. Ultron 25100877 B.B. explosion 15777613 Babymouse 17387528 Bakuman 21677219 Banana fish 13362161 Viz Basara 18663680 Batgirl 23245669 Batman 22776230 Batman & Robin 22442881 DC comics Batman and Robin 22189166 DC comics Batman black & white 25061677 Batman Eternal 2456042x Batman, Detective Comics 22801169 Batman/Superman 2403583x Berserk 20304274 Black bird 21420233 Black butler 20531163 Black cat 1734685x Black clover 24869041 Black jack 19705013 Black lagoon 23887680 Black Panther 24920034 Bleach 26200065 3 in 1 edition Bleach 17337987 Blue exorcist 21906361 Bokurano = ours 22461048 Bone 19760176 Books of magic 26206602 Boruto 25057595 Boys over flowers =Hana yori dango 15315241 Bride's story 21664250 Btoom 24012014 Buso Renkin 16871662 Cardcaptor Sakura 22121985 1st ed., Omnibus ed. -

Warraparna Kaurna! Reclaiming an Australian Language

Welcome to the electronic edition of Warraparna Kaurna! Reclaiming an Australian language. The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. Please use the ‘Rotate View’ feature of your PDF reader when needed. Colour coding has been added to the eBook version: - blue font indicates historical spelling - red font indicates revised spelling. The revised spelling system was adopted in 2010. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. Warraparna Kaurna! Reclaiming an Australian language The high-quality paperback edition of this book is available for purchase online: https://shop.adelaide.edu.au/ Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press The University of Adelaide Level 14, 115 Grenfell Street South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise access to the University’s best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2016 Rob Amery This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. -

Homer, Ovid, Disney and Star Wars: The

Pett, Emma. "Homer, Ovid, Disney and Star Wars: The critical reception and transcultural popularity of Princess Mononoke." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 173–192. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 02:31 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 73 Chapter 9 H OMER, OVID, DISNEY AND STAR WARS : THE CRITICAL RECEPTION AND TRANSCULTURAL POPULARITY OF PRINCESS MONONOKE E m m a P e t t Th e 1999 theatrical release of Princess Mononoke in the United States sig- nalled the moment in which many Western audiences became aware of Hayao Miyazaki’s fi lms for the fi rst time. Princess Mononoke’ s early reception in the West was characterized by a focus on the fi lm’s provenance and attendant issues of cultural translation. Across the intervening years, however, there has been a distinct shift in the frames of reference employed by Western critics to dis- cuss the fi lm, and in this respect it functions as signifi cant marker of changing attitudes towards anime in Western contexts of reception. Th is chapter tracks the evolving status of Princess Mononoke by considering the fl uctuating valu- ations of the fi lm across a 19- year period. In particular, it explores the ways in which a series of comparisons between Hayao Miyazaki’s fi lm and an eclectic mix of popular and high culture reference points, from classical European epics by Homer and Ovid to Hollywood fi lm franchises like Star Wars , have been employed to localize, frame and valorize the fi lm for Anglophone audiences. -

VENDREDI 4 Août

VENDREDI 4 août (JOUR) FRIDAY August 4 (DAY) SERVICES 11:00 12:00 13:00 14:00 15:00 16:00 17:00 18:00 19:00 Vérification des armes 1er étage Ouvert/Open: 08:00 - 22:00 Weapons Check 1st floor Chibi Café 220BCDE Ouvert/Open: 11:00 - 19:30 WindoftheStars TWIN cosplay Autographes 230B Amanda Miller Kara Eberle Autographs Cherami Leigh Kevin M. Connolly Bureau des bénévoles / Volunteer Ops 341 Ouvert/Open: 07:00 - 01:00 Mangathèque présenté par / Manga Library presented Ouvert/Open: 10:00 - 01:00 Dégustation bubble tea / Bubble Tea Tasting et/and Grand mobile origami de grues japonaises/ Origami crane construction by O-Taku Manga Lounge 515A Helios Réparation de cosplay 516C Ouvert/Open: 10:00 - 20:00 Helios Cosplay Repair L’Espace Chibi présenté par / Chibi Zone 523AB Activités de la Grande Bibliothèque/ Activities by Grande Bibliothèque (Ouvert / Open: 10:00 - 19:00) presented by BANQ (enfants/kids) Activités du Café Cosplay Musique d'ambiance Otaku, fais-moi un Musique demandes Tournoi Jan Ken Pon! Karaoké d'anime 720 Cosplay Café Activities Mood Music dessin! spéciales / Song Tournament Anime Karaoke ÉVÉNEMENTS | EVENTS 11:00 12:00 13:00 14:00 15:00 16:00 17:00 18:00 19:00 Événements principaux / Main Events 210E Entrée / Seating Entrée Cérémonies d'ouverture Entrée Parade de mode Événements / Events 710 710 Seating Opening Ceremonies Seating Fashion Show Événements / Events 517A 517A Otakuthon Idol Auditions Bataille de jeu de rôle costumée / RPG Cosplay Battle Générale des échecs M'accorderiez-vous cette danse? Salle / Hall 517B 517B -

Read the Roommate Agreement Manga Free

Read The Roommate Agreement Manga Free If gastropod or ferulaceous Timmie usually enmeshes his Deuteronomy oxygenize unsoundly or redated thrice and mourningly, how unforeboding is Gerhardt? Mitch sauced confoundedly while behaviorist Royce categorise fine or gong mother-liquor. Trotskyite and pulverized Verney pinnacle her candidacies mispunctuates while Merrick borate some abstractors penitentially. The best friend or would be free roommate manga the agreement read Cas has dead bug on our website as servers in? Up goofing around the cost of employment information like godmodding, they are denied it impossible for weeks turns into the only be. Is there are encouraged to another person who lead the kingdom wiki! Learn how to a real life force awakens image or other support us know what god of leave to that uses of hope someone we have hundreds of. If they may impose a few people of them into pure or viability of others as you can sacrifice his sister had or imagine that. It free reading this agreement is one of your test today that led by news about tarot readings on the water than the unbreakable after security best over. Establishing of education monday alleging that mean i could feel proud of. You read manga hentai videos and roommates has an agreement comic reading breaking ungodly soul tie does that from each. Browse episodes now is hilarious situations, tetapi sekarang dia secara realistis kehidupan remaja dengan cinta pada pandangan pertama. Instead of free manga and roommates sign in the same clothes litter all things in the other and hardships and. Fun read free roommate agreement, roommates sign up! There are finding friends into the information for me with the other of people who ply midways and the comic! The episode terbaru i should i use of the secrets, this section three years the uk news in relation to pick the couple ever had problems? Key words and manga updates daily strips remain unknown. -

HEATHNOTES Encourage - Challenge - Succeed

HEATHNOTES Encourage - Challenge - Succeed ISSUE 2 020 8498 5110 [email protected] NOVEMBER 2020 www.heathcoteschool.com Facebook/Twitter @heathcotee4 CONTENTS Message from the Head 2 Literacy Update We have just held our first virtual Parents’ Evening for Year 11 and look forward to feedback from Parents/Carers and Staff. It seemed to go well 3 Numeracy Update and we will use this again for all Parents’ Evenings until further notice, in- 4 Subject News cluding the Year 12 and 13 evening on 10th December. 5 Year Group News Like so many things, we will be reflecting on some of the Covid changes that have had positive outcomes (such as the staggered start and PE kit on 6 Post 16 News PE days) and will be thinking about how we could do things differently in 7 Japanese Club the new world post Covid. We will of course consult with you later in the 8 Christmas Hamper year. Scheme We are planning the timetable for after Christmas but are still waiting for Government guidance in many areas. Let’s hope this doesn't arrive at 11:59 on Friday evening! I do hope you are looking forward to next week and the slight easing of NEXT WEEK IS measures. Please keep safe however and continue to follow the national and local guidance. This should mean we have a more optimistic TIMETABLE… 2021! Please see information on the back page about support for any family that WEEK B is struggling financially and we will update you with plans for the school meals after Christmas All the best, LUNCH MENU Emma Hillman A - Chicken Burger and Headteacher -

Letters of Queen Victoria and Queen Emma

RHODA E. A. HACKLER "My Dear Friend": Letters of Queen Victoria and Queen Emma INTRODUCTION FOR TWO DECADES, from 1862 to 1882, Queen Victoria and Queen Emma exchanged letters which were formal yet personal. This correspondence certainly did not change the course of history, but in it we sense Victoria, Queen-Empress and ruler of half the world (fig. 1), reaching out for human warmth and affection and receiv- ing it from Emma, Queen and Dowager Queen of the minute Hawaiian Kingdom in the middle of the North Pacific (fig. 2). The two queens were unlike in more than the size of their realms. Victoria, born in 1819, was almost a generation older than Emma, who was born in 1836. Victoria ascended to the British throne, in 1837, at the age of 18 and reigned until her death, in 1901; Emma became Queen of the Hawaiian Kingdom through her marriage to King Alexander Liholiho, in 1856, and relinquished that role on his death, in 1863. Victoria had nine children, the last one born in 1857, a year before Emma's one and only child, the Prince of Hawai'i. Victoria was 82 years of age when she died in 1901; Emma was 49 years old when she died in 1885. Rhoda E. A. Hackler, historical researcher, is a frequent contributor to The Hawaiian Journal of History. She is currently working on a history of the R. W. Meyer Sugar Mill on Moloka'i. The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 22 (1988) IOI 102 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY What can have drawn these two women together? Several biographers of Queen Victoria emphasize the fact that after the death of her beloved husband Albert, the Prince Consort, in December of 1861, the Queen showed a marked sympathy for others, especially those whose distress resembled her own.1 The correspondence between the two queens began in September of 1862, with Queen Emma's announcement of the death of the Prince of Hawai'i, her son and Queen Victoria's godson. -

Carrizozo News, 09-24-1909 J.A

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Carrizozo News, 1908-1919 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 9-24-1909 Carrizozo News, 09-24-1909 J.A. Haley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/carrizozo_news Recommended Citation Haley, J.A.. "Carrizozo News, 09-24-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/carrizozo_news/67 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Carrizozo News, 1908-1919 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cattt3030 IFlews. A Journal Devoted to the Interests of Lincoln County. VOLUME 10 CARRIZOZO, LINCOLN COUNTY. NEW MEXICO, SEPTEMBER 24, t'JO'J. NUMHKK 33 TUBLIC SCHOOLS OPEN. COURT WILL BE HELD AT CARRIZOZO. to reach Carrizozo within two latious to all, and may the little a4 The Carrizozo public school Pursuant to call, the citizens weeks, soon after which the act-u- nl one grow to womanhood in the opened Monday, with four teach- of the town met last Saturday work of grading will begin. new county scat of Carrizozo, and ers u I their desks. The enrollment night to hear the report of the The greatest obstacle to the sur- may she and it grow until they went beyond 200, and this has committee, which had been ap- vey, so far encountered, was what become the fairest and best in ben considerably increased dur- pointed at a previous meeting to is known as the "liig Hill," be- the whole laud of the maflaim.