The Art and Science of Somatic Praxis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychotherapeutic Postural Integration (IPP)

Member of the Fédération Française de Psychothérapie et Psychanalyse (FF2P) Institute Accredited by the European Association of Psychotherapy Psychotherapeutic Postural Integration (IPP) By Eliane and Claude Vaux Société Civile IFCC – SIRET 405 186 875 00036 – 102 Route du Polygone – 67100 Strasbourg Tel: 0033 (0)3 88 60 44 84 – Email: [email protected] – Site: www.ifcc-psychotherapie.fr 1 2 Short history The IFCC was founded in 1996 with enthusiasm and joy. Eliane Jung-Fliegans, clinical psychologist, and Claude Vaux, body psychotherapist, combined their expertise and their passion for this work since 1982 and decided to create a psychotherapy training course mainly focused on Gestalt Therapy and Postural Integration. At the time, Claude Vaux was working in Paris at the Triangle association, with Michel Sokoloff and Dominique Vayner. Triangle opens the field to new therapies from the USA and from India by organizing seminars and training courses. In this way, they bring to France a range of therapists known in Esalen, cradle of humanist psychology, such as Léonard Orr, creator of Rebirth, Paul Rebillot, founder of Experiential Gestalt, Alexander Lowen, founder of Bioenergetic Analysis, Gerda Boyesen, creator of Biodynamics, Harvey Jackins, founder of Co-Counseling, Jack Painter, creator of Postural Integration… Eliane, after obtaining a master’s degree in psychology, created the Cabinet of Humanist Psychology in Strasbourg, where she practices Gestalt Therapy and Creative Visualization. Little by little, the method they teach became more and more distinctive and eventually unified under the name of Psychotherapeutic Postural Integration. Claude and Eliane collaborate with Jack Painter and Paul Rebillot, but above all integrate into their training the Regenerative Movement taught by Itsuo Tsuda, whom Claude met in 1978. -

December 2007

December 2007 Issue 5 ISSN 1553-3069 Table of Contents Editorial A Time of Transition ................................................................ 1 Jonathan Reams Peer Reviewed Works The Evolution of Consciousness as a Planetary Imperative: An Integration of Integral Views ............................................................. 4 Jennifer Gidley Editorially Reviewed Works Towards an Integral Critical Theory of the Present Age ..................... 227 Martin Beck Matuštík Illuminating the Blind Spot: An Overview and Response to Theory U ............................................ 240 Jonathan Reams Sent to Play on the Other Team ........................................................... 260 Josef San Dou Art and the Future: An Interview with Suzi Gablik ............................. 263 Russ Volckmann cont'd next page ISSN 1553-3069 Reactivity to Climate Change .............................................................. 275 Jan Inglis Developing Integral Review: IR Editors Reflect on Meta-theory, the Concept of "Integral," Submission Acceptance Criteria, our Mission, and more............................................................................................... 278 IR Editors ISSN 1553-3069 Editorial A Time of Transition As we welcome you to the fifth semi-annual issue of Integral Review (IR), I would like to point to signs that mark a time of transition for this journal. Some are small, like shifting our table of contents headings to more clearly identify which works are peer reviewed, and changing the spacing between articles’ paragraphs. Others are more obvious, like the ability and willingness to publish even longer works than previously, in addition to the ongoing array of works published. Some transitions are in process and less visible. For example, we are working to evolve IR’s structure to reflect its degree of engagement from others, and making behind the scene shifts in our ability to better understand and realize the goals we set out to accomplish. -

Here They Appear) for Non-Commercial Use Or Use Sincere Thanks and Acknowledgement Also Go To: Within Your Organisation

Massage Therapy Code of Practice association of massage therapists page 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Code of Practice would not have come into © Association of Massage Therapists Ltd being without the effort, commitment and energy of a number of people. Special acknowledgement This material is copyright © Association of Massage is due to Rebecca Barnett, Tamsin Rossiter and Therapists Ltd (AMT). You may download, store in Desley Scott who researched and wrote most of the cache, display, print and reproduce the material in standards contained in this document. unaltered form only (retaining this notice, or links to it where they appear) for non-commercial use or use Sincere thanks and acknowledgement also go to: within your organisation. You may not deal with the material in a manner that might mislead or deceive • Alan Ford and Linda Hunter, any person. who drafted three of the Standards in the Code You may not reproduce this material without • Beth Wilson and Grant Davies acknowledging AMT's authorship. (Office of the Health Services Commissioner, Victoria) and Professor Michael Ward (Health Quality Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright and Complaints Commission, Queensland) who Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests for provided invaluable feedback and insight further authorisation should be directed to: • Colin Rossie, whose research and contributions Association of Massage Therapists Ltd to the Code of Practice Wiki helped to maximise PO Box 826 stakeholder engagement in the process Broadway NSW 2007 P: 02 9211 2441 • Annette Cassar and Jodee Shead, E: [email protected] who assisted in the review process • Linda White, Paul Lindsay and Katie Snell, who proofed the document • All those who took the time to read the draft Code and provide feedback. -

Dare I Touch? Exploring the Potentials of Using Touch in Neuro-Linguistic-Psychotherapy Asaf Rolef Ben-Shahar

Dare I touch? Exploring the Potentials of using touch in Neuro-Linguistic-Psychotherapy Asaf Rolef Ben-Shahar Touch remains the most trusted connection between people. I will believe your touch before I believe your words. Virginia Satir (1988) I breathe. I come to my centre. What does it mean to come to my centre, for me? It means being at home with me; it means being ok with the thoughts, sensations, emotions, being ok with me. Moreover, it means making a statement to the world about being me: it’s ok. Strangely, it is when I’m mostly in my centre, that I’m also mostly connected to others. This is nothing new, I haven’t invented any novelty; different people in different cultures have talked about these moments. I breathe. I come to my centre and connect with you through my centre. We watch each other, we sense each other’s presence; we touch. What could be more wonderful than this celebration of life? What could be scarier than this celebration of life? And in those moments it doesn’t matter that I am a therapist and you are a client (or vice-versa). In those moments we are. And when I am, then all is ok, and when you are all is ok. And techniques? And changework? And achieving the client’s outcome? Well, techniques is what we do when being isn’t that easy, isn’t it? Some people are afraid of trance; they are fearful because trance opens the door to powerful change, it opens doors to genuine and authentic magic. -

MBLX Final Review 112 Questions MBLX Review

Instructor’s Review for Final Exams MBLX Final Review 112 Questions MBLX Review Plain & Simple Guide to Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork Examinations Client History General Review 1. A client comes in and reports that her lower back has been hurting ever since she mowed her lawn yesterday. In which section of the SOAP notes is this information recorded? a. S b. O c. A d. P General Review 2. To assist in making a postural assessment, you could use ______. a. A plumb line b. A grid c. Two pieces of tape on the wall d. All of the above General Review 3. SOAP is the acronym for ______. a. Structure, Objective, Assessment, Protocol b. Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Practice c. Subjective, Observation, Action, Plan d. Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan General Review 4. Informed consent should be obtained from each client. You should obtain it _____. a. Before doing any work on the client b. Before the client leaves the office c. After the client has completed one session d. While the client is on the table General Review 5. Your client is experiencing pain in the arm, wrist, and hand. You are pretty sure he has carpal tunnel syndrome. You should take the following action: a. Share your diagnosis with the client b. Apply a heating pad for a short time followed by cryotherapy c. Tell him to take a couple of aspirin for the pain, and give him some exercises to do at home d. Suggest that he see his doctor for a diagnosis General Review 6. Touching and feeling the muscles for signs of tautness or trauma is referred to as ______. -

Following the Trail of the Snake: a Life History of Cobra Mansa “Cobrinha” Mestre of Capoeira

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FOLLOWING THE TRAIL OF THE SNAKE: A LIFE HISTORY OF COBRA MANSA “COBRINHA” MESTRE OF CAPOEIRA Isabel Angulo, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Directed By: Dr. Jonathan Dueck Division of Musicology and Ethnomusicology, School of Music, University of Maryland Professor John Caughey American Studies Department, University of Maryland This dissertation is a cultural biography of Mestre Cobra Mansa, a mestre of the Afro-Brazilian martial art of capoeira angola. The intention of this work is to track Mestre Cobrinha’s life history and accomplishments from his beginning as an impoverished child in Rio to becoming a mestre of the tradition—its movements, music, history, ritual and philosophy. A highly skilled performer and researcher, he has become a cultural ambassador of the tradition in Brazil and abroad. Following the Trail of the Snake is an interdisciplinary work that integrates the research methods of ethnomusicology (oral history, interview, participant observation, musical and performance analysis and transcription) with a revised life history methodology to uncover the multiple cultures that inform the life of a mestre of capoeira. A reflexive auto-ethnography of the author opens a dialog between the experiences and developmental steps of both research partners’ lives. Written in the intersection of ethnomusicology, studies of capoeira, social studies and music education, the academic dissertation format is performed as a roda of capoeira aiming to be respectful of the original context of performance. The result is a provocative ethnographic narrative that includes visual texts from the performative aspects of the tradition (music and movement), aural transcriptions of Mestre Cobra Mansa’s storytelling and a myriad of writing techniques to accompany the reader in a multi-dimensional journey of multicultural understanding. -

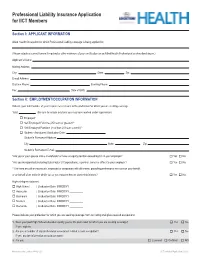

Professional Liability Insurance Application for IICT Members

Professional Liability Insurance Application for IICT Members Section I: APPLICANT INFORMATION Allied Health Occupation for which Professional Liability coverage is being applied for: (Please attach a current license if required or other evidence of your certification as anAllied Health Professional as described above.) Applicant’s Name: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: E-mail Address: Daytime Phone: Evening Phone: Fax: Date of Birth: Section II: EMPLOYMENT/OCCUPATION INFORMATION Indicate your total number of years experience relevant to the profession for which you are seeking coverage. Total: (Be sure to include any time you may have worked under supervision) o Employed* o Self-Employed Full-time (25 hours or greater)** o Self-Employed Part-time (less than 25 hours a week)** o Student - Anticipated Graduation Date: Student’s Permanent Address: City: State: Zip: Student’s Permanent E-mail: *Are you or your spouse also a shareholder or have an equity position exceeding 5% in your employer? o Yes o No *Are you incorporated (including Sub chapter S Corporations), a partner, owner or officer to your employer? o Yes o No **Are there any other individuals, employed or associated with otherwise, providing professional services on your behalf, or on behalf of an entity in which you or your spouse has an ownership interest? o Yes o No Highest degree obtained: o High School | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Associate | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Bachelors | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Masters | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Doctorate | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ Please indicate your profession for which you are seeking coverage from our listing of eligible covered occupations: ______________________________________ 1. -

Defining-Reflex.Pdf

REPORT: DEFINITIONS OF REFLEXOLOGY Prepared by Christine Issel with assistance from Bill Flocco Originally prepared for the America Reflexology Certification Board & Reflexology Association of America May 2003 updated November 2013 1 INTRODUCTION In order to have a unified profession we must seek to establish a unified definition to which most reflexologists can subscribe. In trying to create this universal definition several issues need to be kept in mind. 1. As we move forward in legislative endeavors at any level, it is important to have a similar definition in use and seen in printed literature by the different agencies representing reflexology. There is a national movement to assign billing codes to complementary therapies so that their practitioners can bill through insurance companies. However, in order to do that the practitioner must be licensed by the state*. So we will see more, not less legislation in the years ahead. (*Unlicensed professionals will be able to bill through a licensed practitioner to receive payment.) 2. A definition by the Reflexology Association of America (RAA) must be inclusive, to allow as many reflexologists as possible to subscribe to and thus become members of the association, without being too general as to be meaningless. Whereas a definition by the American Reflexology Certification Board (ARCB) needs to include what it tests. 3. With the best of intent, many reflexologists sometimes want to put as much as possible into a definition. Many people confuse a definition (which defines the word, or what is meant by the word Reflexology) with a scope of practice (what part of the body we work on), the theory (how it is believed to work), the application of techniques (the techniques used and how applied), its history or origin, it’s results or benefits (how it is going to help people). -

Professional Liability Insurance Application for IICT Members

Professional Liability Insurance Application for IICT Members Section I: APPLICANT INFORMATION Allied Health Occupation for which Professional Liability coverage is being applied for: (Please attach a current license if required or other evidence of your certification as anAllied Health Professional as described above.) Applicant’s Name: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: E-mail Address: Daytime Phone: Evening Phone: Fax: Date of Birth: Section II: EMPLOYMENT/OCCUPATION INFORMATION Indicate your total number of years experience relevant to the profession for which you are seeking coverage. Total: (Be sure to include any time you may have worked under supervision) o Employed* o Self-Employed Full-time (25 hours or greater)** o Self-Employed Part-time (less than 25 hours a week)** o Student - Anticipated Graduation Date: Student’s Permanent Address: City: State: Zip: Student’s Permanent E-mail: *Are you or your spouse also a shareholder or have an equity position exceeding 5% in your employer? o Yes o No *Are you incorporated (including Sub chapter S Corporations), a partner, owner or officer to your employer? o Yes o No **Are there any other individuals, employed or associated with otherwise, providing professional services on your behalf, or on behalf of an entity in which you or your spouse has an ownership interest? o Yes o No Highest degree obtained: o High School | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Associate | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Bachelors | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Masters | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ o Doctorate | Graduation Date: MM/DD/YY __________ Please indicate your profession for which you are seeking coverage from our listing of eligible covered occupations: ______________________________________ 1. -

NARRATIVES of NOTHING in TWENTIETH-CENTURY LITERATURE by MEGHAN CHRISTINE VICKS B.A., Middlebury College, 2003 M.A., University of Colorado, 2007

NARRATIVES OF NOTHING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY LITERATURE by MEGHAN CHRISTINE VICKS B.A., Middlebury College, 2003 M.A., University of Colorado, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature 2011 This thesis entitled: Narratives of Nothing in Twentieth-Century Literature written by Meghan Christine Vicks has been approved for the Department of Comparative Literature _________________________________________________ Mark Leiderman _________________________________________________ Jeremy Green _________________________________________________ Rimgaila Salys _________________________________________________ Davide Stimilli _________________________________________________ Eric White November 11, 2011 The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned disciple. iii Vicks, Meghan Christine (Ph.D., Comparative Literature) Narratives of Nothing in Twentieth-Century Literature Thesis directed by Associate Professor Mark Leiderman (Lipovetsky) This study begins with the observation that much of twentieth-century art, literature, and philosophy exhibits a concern with nothing itself. Both Martin Heidegger and Jean Paul Sartre, for example, perceive that nothing is part-and-parcel of (man’s) being. The present study adopts a similar position concerning nothing and its essential relationship to being, but adds a third element: that of writing narrative. This relationship between nothing and narrative is, I argue, established in the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, Mikhail Bakhtin, Jacques Derrida, and Julia Kristeva. As Heidegger and Sartre position nothing as essential to the creation of being, so Nietzsche, Bakhtin, Derrida, and Kristeva figure nothing as essential to the production of narrative. -

Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia Michael David Lawson East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2019 Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia Michael David Lawson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Disability Studies Commons, European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Folklore Commons, History of Religion Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Scandinavian Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Michael David, "Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3538. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3538 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Children of a One-Eyed God: Impairment in the Myth and Memory of Medieval Scandinavia ————— A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University ————— In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree -

Adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents

.....••_•____________•. • adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents Ordering Information 2 Arabic * Middle Eastern 51 Order Blank 3 Jewish 52 About Ladyslipper 4 Alternative 53 Donor Discount Club * Musical Month Club 5 Rock * Pop 56 Readers' Comments 6 Folk * Traditional 58 Mailing List Info * Be A Slipper Supporter! 7 Country 65 Holiday 8 R&B * Rap * Dance 67 Calendars * Cards 11 Gospel 67 Classical 12 Jazz 68 Drumming * Percussion 14 Blues 69 Women's Spirituality * New Age 15 Spoken 70 Native American 26 Babyslipper Catalog 71 Women's Music * Feminist Music 27 "Mehn's Music" 73 Comedy 38 Videos 77 African Heritage 39 T-Shirts * Grab-Bags 82 Celtic * British Isles 41 Songbooks * Sheet Music 83 European 46 Books * Posters 84 Latin American . 47 Gift Order Blank * Gift Certificates 85 African 49 Free Gifts * Ladyslipper's Top 40 86 Asian * Pacific 50 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fri 9-8, Sat'11-5) Ordering Information INFORMATION: 919-683-1570 (same as above) FAX: 919-682-5601 (24 hours'7 days a week) PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available. LP = record, CS = cassette, CD = com schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives pact disc. Some recordings are available only on LP Ladyslipper, Inc.