Losing Papa 1 Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[T] IMRE PALLÓ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5305/t-imre-pall%C3%B3-725305.webp)

[T] IMRE PALLÓ

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs FRANZ (FRANTISEK) PÁCAL [t]. Leitomischi, Austria, 1865-Nepomuk, Czechoslo- vakia, 1938. First an orchestral violinist, Pácal then studied voice with Gustav Walter in Vienna and sang as a chorister in Cologne, Bremen and Graz. In 1895 he became a member of the Vienna Hofoper and had a great success there in 1897 singing the small role of the Fisherman in Rossini’s William Tell. He then was promoted to leading roles and remained in Vienna through 1905. Unfor- tunately he and the Opera’s director, Gustav Mahler, didn’t get along, despite Pacal having instructed his son to kiss Mahler’s hand in public (behavior Mahler considered obsequious). Pacal stated that Mahler ruined his career, calling him “talentless” and “humiliating me in front of all the Opera personnel.” We don’t know what happened to invoke Mahler’s wrath but we do know that Pácal sent Mahler a letter in 1906, unsuccessfully begging for another chance. Leaving Vienna, Pácal then sang with the Prague National Opera, in Riga and finally in Posen. His rare records demonstate a fine voice with considerable ring in the upper register. -Internet sources 1858. 10” Blk. Wien G&T 43832 [891x-Do-2z]. FRÜHLINGSZEIT (Becker). Very tiny rim chip blank side only. Very fine copy, just about 2. $60.00. GIUSEPPE PACINI [b]. Firenze, 1862-1910. His debut was in Firenze, 1887, in Verdi’s I due Foscari. In 1895 he appeared at La Scala in the premieres of Mascagni’s Guglielmo Ratcliff and Silvano. Other engagements at La Scala followed, as well as at the Rome Costanzi, 1903 (with Caruso in Aida) and other prominent Italian houses. -

Architecture As Frozen Music: Italy and Russia in the Context of Cultural Relations in the 18Th -19Th Centuries

Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts - Volume 4, Issue 2 – Pages 123-132 Architecture as Frozen Music: Italy and Russia in the Context of Cultural Relations in the 18th -19th Centuries By Tatiana Samsonova This article deals with the two kinds of art, architecture and music, in their stylistic mutual influence on the historical background of St. Petersburgʼs founding and developing as the new capital of the Russian Empire in the early 18th century. The author highlights the importance of Italian architects and musicians in the formation of modern culture in Russia and shows how the main features of Baroque and Classicism are reflected both in the architecture and music thanks to the influence of the Italian masters. For the first time the issue of the "Russian bel canto" formation resulted from the Italian maestros working in Russia in 18–19 centuries is revealed. Russian-Italian relations originated in the 18th century and covered various cultural phenomena. Their impact is vividly seen in architecture and music in St. Petersburg, which was founded in 1703 by the Russian Emperor Peter the Great whose strong desire was to turn Russia into Europe. As the famous Russian poet Alexander Pushkin wrote in his "The Bronze Horseman" (1834), "the Emperor cut a Europe window." For St. Petersburg construction as a new Russian capital outstanding Italian architects were invited. The first Italian architect, who came to St. Petersburg, was Domenico Trezzini (1670- 1734), a famous European urban designer and engineer. In the period of 1703- 1716 he was the only architect working in St. Petersburg and the Head of City Development Office. -

MS 254 A980 Women's Campaign for Soviet Jewry 1

1 MS 254 A980 Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry 1 Administrative papers Parliamentary Correspondence Correspondence with Members of Parliament 1/1/1 Members of Parliament correspondence regarding support for the 1978-95 efforts of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry and brief profiles and contact details for individual Members of Parliament; Diane Abbot, Robert Adley, Jonathan Aitken, Richard Alexander, Michael Alison, Graham Allen, David Alton, David Amess, Donald Anderson, Hilary Armstrong, Jacques Arnold, Tom Arnold, David Ashby, Paddy Ashdown, Joe Ashton, Jack Aspinwall, Robert Atkins, and David Atkinson 1/1/2 Members of Parliament correspondence regarding support for the 1974-93 efforts of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry and brief profiles and contact details for individual Members of Parliament; Kenneth Baker, Nicholas Baker, Tony Baldry, Robert Banks, Tony Banks, Kevin Barron, Spencer Batiste and J. D. Battle 1/1/3 Members of Parliament correspondence regarding support for the 1974-93 efforts of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry and brief profiles and contact details for individual Members of Parliament; Margaret Beckett, Roy Beggs, Alan James Beith, Stuart Bell, Henry Bellingham, Vivian Bendall, Tony Benn, Andrew F. Bennett, Gerald Bermingham, John Biffen, John Blackburn, Anthony Blair, David Blunkett, Paul Boateng, Richard Body, Hartley Booth, Nichol Bonsor, Betty Boothroyd, Tim Boswell and Peter Bottomley 1/1/4 Members of Parliament correspondence regarding support for the 1975-94 efforts of the Women’s Campaign -

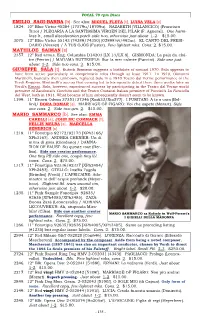

18.5 Vocal 78S. Sagi-Barba -Zohsel, Pp 135-170

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs EMILIO SAGI-BARBA [b]. See also: MIGUEL FLETA [t], LUISA VELA [s] 1824. 10” Blue Victor 45284 [17579u/18709u]. NAZARETH [VILLANCICO] (Francisco Titto) / PLEGARIA A LA SANTISSIMA VIRGEN DEL PILAR (F. Agüeral). One harm- less lt., small discoloration patch side two, otherwise just about 1-2. $15.00. 3075. 12” Blue Victor 55143 (74389/74350) [02898½v/492ac]. EL CANTO DEL PRESI- DARIO (Alvarez) / Á TUS OJOS (Fuster). Few lightest mks. Cons . 2. $15.00. MATHILDE SAIMAN [s] 2357. 12” Red acous. Eng. Columbia D14203 [LX 13/LX 8]. GISMONDA: La paix du cloï- tre (Février) / MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Sur la mer calmée (Puccini). Side one just about 1-2. Side two cons . 2. $15.00. GIUSEPPE SALA [t]. Kutsch-Riemens suggests a birthdate of around 1870. Sala appears to have been active particularly in comprimario roles through at least 1911. 1n 1910, Giovanni Martinelli, basically then unknown, replaced Sala in a 1910 Teatro dal Verme performance of the Verdi Requiem . Martinelli’s sucess that evening led to his operatic debut there three weeks later as Verdi’s Ernani. Sala, however, experienced success by participating in the Teatro dal Verme world premiere of Zandonai’s Conchita and the Teatro Costanzi Italian premiere of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West , both in 1911. What became of him subsequently doesn’t seem to be known. 1199. 11” Brown Odeon 37351/37346 [Xm633/Xm577]. I PURITANI: A te o cara (Bel- lini)/ DORA DOMAR [s]. MARRIAGE OF FIGARO: Voi che sapete (Mozart). Side one cons. 2. Side two gen . 2. -

ARSC Journal Encourages Recording Companies and Distributors to Send New Releases of Historic Recordings to the Sound Recording Review Editor

COMPILED BY CHRISTINA MOORE Recordings Received This column lists historic recordings which have been defined as 20 years or older. Historic recordings with one or two recent selections may be included as well. The ARSC Journal encourages recording companies and distributors to send new releases of historic recordings to the Sound Recording Review Editor. Anakkta: Les Grandes Voix du Canada/Great Voices of Canada, Volume 1. Selections by Jeanne Gordon, Edward Johnson, Joseph Saucier, Florence Easton, Sarah Fischer, Rodolphe Plamondon, Emma Albani, Eva Gauthier, Paul Dufault, Louise Edvina, Pauline Donalda, Raoul Jobin. Analekta AN 2 7801. CD, recorded 1903-1958. Les Grandes Voix du Canada/Great Voices of Canada, Volume 2. Edward Johnson, tenor: selections from Andrea Chenier, La Boheme, La Fanciulla del West, Pagliacci, Louise, Parsifal, Elijah, Fedora, songs, etc. Analekta AN 2 7802. CD, recorded 1914-1928. Les Grandes Voix du Canada/Great Voices of Canada, Volume 3. Raoul Jobin, tenor, en concert/live: selections from Herodiade, Madama Butterfly, La Fille du Regiment, Carmen, Louise, Lakme, Les Pecheurs de Perles, etc. Analekta AN 2 8903. CD, recorded 1939-1946. Arhoolie Productions, Inc.: Don Santiago Jimenez. His First and Last Recordings. La Dueiia de la Llave; La Tuna; Eres un Encanto; Antonio de Mis Amores; El Satelite; Ay Te Dejo en San Antonio; El Primer Beso; Las Godornises; Vive Feliz; etc. Arhoolie CD-414 (1994). CD, recorded 1937-38and1979. Folksongs of the Louisiana Acadians. Selections by Chuck Guillory, Wallace "Cheese" Read, Mrs. Odeus Guillory, Mrs. Rodney Fruge, Isom J. Fontenot, Savy Augustine, Bee Deshotels, Shelby Vidrine, Austin Pitre, Milton Molitor. -

Russian Minority in Latvia

Russian Minority in Latvia EXHIBITON CATHALOG Foundation of MEP Tatjana Ždanoka “For Russian Schools”, Riga-Brussels 2008-2009 Riga-Brussels 2008-2009 The Exhibition “Russian Minority in Latvia” is supported by the Foundation of MEP Tatjana Ždanoka “For Russian Schools”, by European Parliament political group “Greens/EFA” as well as the External Economic and International Relations Department of Moscow City Government and the Moscow House of Fellow Nationals. Author Team: Tatjana Feigman and Miroslav Mitrofanov (project managers) Alexander Gurin, Illarion Ivanov, Svetlana Kovalchuk, Alexander Malnach, Arnold Podmazov, Oleg Puhlyak, Anatoly Rakityansky, Svetlana Vidyakina Design by Victoria Matison © Foundation “For Russian Schools” ISBN 978-9984-39-661-3 The authors express their gratitude for assistance and consultation to the following: Metropolitan of Riga and all Latvia Alexander Kudryashov and priest Oleg Vyacheslav Altuhov, Natalia Bastina, Lev Birman, Valery Blumenkranz, Olga Pelevin, Bramley (UK), Vladimir Buzayev, Valery Buhvalov, Dzheniya Chagina, Yury Chagin, Chairman of the Central Council of Latvian Pomorian Old Orthodox Church Biruta Chasha, Alexey Chekalov, Irina Chernobayeva, Nataliya Chekhova, Elina Aleksiy Zhilko, Chuyanova, Vitaly Drobot, Yevgeny Drobot, Dmitry Dubinsky, Nadezhda Dyomina, Editor in chief of daily newspaper “Vesti Segodnya” Alexander Blinov, the Vladimir Eihenbaum, Xenia Eltazarova, Zhanna Ezit, Lyudmila Flam (USA), vice-editor in chief Natalya Sevidova, journalists Yuliya Alexandrova and Ilya Svetlana -

September 2018

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Ludmila & Paul Kulikovsky №126 September 2018 The "Romanov Griffin" on the Romanov Boyar House in Moscow "The last Tsar: Blood and Revolution" In the London Museum of Science, on 21 September, an exhibition dedicated to the last Russian Emperor was opened. The exposition is timed to the anniversary of the tragic death of the Romanov family. It is based on photographs, paintings, garments and ornaments, rare artefacts from archives, museums and private collections in Russia, United Kingdom and the United States. "We wanted to tell the story of the Romanovs differently, because people think about them in a rather sentimental way, but in fact, the Emperor [Nicholas II] can be called the pioneer of the scientific progress of his time," said the Director of the Museum of Science, Ian Blatchford. He also mentioned it demonstrates the inconsistency of the figure of the last Russian Emperor, when, being a progressive person in some matters, in others he was afraid of this very progress. "Nicholas II read the work of Leo Tolstoy for the first time after the abdication, for me this discovery was shocking because in British education this is the basis of Russian literature and any British schoolchild knows such names as Anna Karenina, and "War and Peace", "The fact that the Tsar got acquainted with this literature only at the end of his life means to me that he was also opposed to progress, I would call this the "Russian paradox" of the Romanovs, a controversial moment." Ian Blatchford, Director of the Science Museum, explained how the roots of the exhibition lie in "Cosmonauts", the first international exhibition about how Russia won the original space race. -

Soloists of the Bolshoi Theatre Поют Солисты Большого Театра Союза CCP Mp3, Flac, Wma

Soloists Of The Bolshoi Theatre Поют Солисты Большого Театра Союза CCP mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Поют Солисты Большого Театра Союза CCP Country: USSR Released: 1985 MP3 version RAR size: 1794 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1924 mb WMA version RAR size: 1564 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 945 Other Formats: WAV RA MP3 VOC MP4 MPC DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Onegin's Aria ("Eugene Onegin", Act I) A1 –P. Tchaikovsky* 4:46 Baritone Vocals – Yuri Mazurok Marina's Aria ("Boris Godunov", Act II) A2 –M. Mussorgsky* 3:17 Mezzo-soprano Vocals – Elena Obraztsova Hermann's Arioso ("The Queen Of Spades", Act I) A3 –P. Tchaikovsky* 3:18 Tenor Vocals – Vladimir Atlantov The Miller's Aria ("The Rusalka", Act I) A4 –A. Dargomyzhsky* 4:26 Bass Vocals – Alexander Vedernikov* Kuma's Aria ("The Enchantress", Act I) A5 –P. Tchaikovsky* 4:05 Soprano Vocals – Tamara Milashkina Farlaf's Rondo ("Ruslan And Ludmila", Act II) A6 –M. Glinka* 3:34 Bass Vocals – Evgeni Nesterenko* Jeanne's Aria ("The Maid Of Orleans", Act I) B1 –P. Tchaikovsky* 6:37 Mezzo-soprano Vocals – Irina Arkhipova* Cavaradossi's Aria ("Tosca", Act III) B2 –G. Puccini* 3:04 Tenor Vocals – Zurab Sotkilava* Volkhova's Cradle Song ("Sadko", Scene 7) B3 –N. Rimsky-Korsakov* 3:12 Soprano Vocals – Bela Rudenko* Demon's Romance ("Demon", Act II) B4 –A. Rubinstein* 4:04 Bass Vocals – Alexander Ognivtsev* Cherubino's Aria ("Le Nozze Di Figaro", Act II) B5 –W. A. Mozart* 2:42 Mezzo-soprano Vocals – Galina Borisova Robert's Arioso ("Iolanta") B6 –P. Tchaikovsky* 2:06 Baritone Vocals – Yuri Gulyaev* Notes Made in USSR Related Music albums to Поют Солисты Большого Театра Союза CCP by Soloists Of The Bolshoi Theatre Tchaikovsky / Solists, Chorus And Orchestra Of The Bolshoi Theatre Conducted By Mstislav Rostropovich - Eugene Onegin Tchaikovsky, Mstislav Rostropovitch Conducting The Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra & Chorus - Eugene Onegin Highlights П. -

MOMENTS MUSICAUX Occasional Essays on Opera

MOMENTS MUSICAUX Occasional Essays on Opera This PDF is one of a series designed to assist scholars in their research on Isaiah Berlin, and the subjects in which he was interested. The series will make digitally available both selected published essays and edited transcripts of unpublished material. The red page numbers in square brackets in this online text mark the beginning of the relevant page in the original publication, and are provided so that citations from book and online PDF can use the same page-numbering. The PDF is posted by the Isaiah Berlin Legacy Fellow at Wolfson College, with the support of the Trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust. All enquiries, including those concerning rights, should be directed to the Legacy Fellow at [email protected] MOMENTS MUSICAUX Occasional Essays on Opera Edited by Henry Hardy Isaiah Berlin’s writings on music have never been printed in collected form. His undergraduate music criticism can be read here. Later critical writing on music is in the process of being posted separately, with links provided in the relevant catalogue entries. This PDF comprises his other principal essays on music, all with operatic subjects. Links to the individual essays appear below. Mozart at Glyndebourne since 1934 Tchaikovsky and Eugene Onegin Khovanshchina Performances memorable – and not so memorable Surtitles © Isaiah Berlin 1971, 1975, 1984, 1986 Editorial matter © Henry Hardy 2019 Posted in Isaiah Berlin Online 5 January 2019 Mozart at Glyndebourne First published as ‘Mozart at Glyndebourne Half a Century Ago’ in John Higgins (ed.), Glyndebourne: A Celebration (London, 1984: Cape), 101–9 I wish that I could say that I was a member of that small company which, drawn by friendship, curiosity, hope, or simple faith, boarded the historic train which went from Victoria to Sussex in May 1934 for the inaugural performance of Le nozze di Figaro. -

Pulitzer Prize-Winner Powers Speaks at Friends of the Libraries Luncheon

MU LIBRARIES Pulitzer Prize-winner Powers Speaks at Friends of the Libraries Luncheon University of Missouri Ron Powers, Doug Crews, Columbia r 1963 graduate of Friends of the Libraries the University of president, led the July 2007 Missouri School luncheon meeting and Volume 3, Number 2 of Journalism and announced the winners a Pulitzer-prize of the 2007 Robert J. winning journalist, Stuckey Essay Contest. told Friends of the Kelly Bouquet, St. MU Libraries about Louis, won first place Table of his childhood love of in the contest with a Contents reading at their 17th monetary award of annual luncheon Ron Powers, BJ ’63, author of $1,500 for her essay, Flags of our Fathers and other r April 14. “Bon Appètit.” Kristy books, described how libraries Powers said his Bass, Jefferson City, FACULTY LECTURE SERIE S influenced his life and career 2 hometown library at the Friends of the Libraries won second place in Hannibal, Mo., Luncheon April 14, 2007. with a $750 award for THE “FARMER S WI F E ” 3 revealed a world of her essay, “Bound to stories to him and helped inspire him be Best Friends.” The teachers of ENDO W MENT GI F T S to become a writer. He signed his two both students received $250 each for HELP STUDENT S 4 recent books, Mark Twain: A Life and encouraging excellence in reading and Flags of Our Fathers, for the group. writing. ABRAHAM LINCOLN EXHIBIT Flags of Our Fathers was recently made Read the award-winning essays on 7 into an award-winning movie directed the Web at mulibraries.missouri.edu/ LOVIN G CUP S GET by Clint Eastwood. -

Tchaikovsky and 'Eugene Onegin'

TCHAIKOVSKY AND EUGENE ONEGIN This PDF is one of a series designed to assist scholars in their research on Isaiah Berlin, and the subjects in which he was interested. The series will make digitally available both selected published essays and edited transcripts of unpublished material. The page numbers in square brackets in this online text mark the beginning of the relevant page in the original publication, and are provided so that citations from book and online PDF can use the same page-numbering. The PDF is posted by the Isaiah Berlin Legacy Fellow at Wolfson College, with the support of the Trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust. All enquiries, including those concerning rights, should be directed to the Legacy Fellow at [email protected] Tchaikovsky and Eugene Onegin Glyndebourne Festival Programme Book 1971, 58–63; repr. as ‘Tchaikovsky, Pushkin and Onegin’ in Musical Times 121 (1980), 163– 8, and in Eugene Onegin (Oxford University Opera Club programme) ([Oxford], 1992); edited by Henry Hardy for online posting 2019 On 18 May 18771 Petr Il′ich Tchaikovsky wrote to his brother Modest Il′ich: Last week I happened to be at Mme Lavrovsky’s. There was talk about suitable subjects for opera. Her stupid husband talked the most incredible nonsense, and suggested the most impossible subjects. Elizaveta Andreevna smiled amiably and did not say a word. Suddenly she said, ‘What about Eugene Onegin?’2 It seemed a wild idea to me, and I said nothing. Then when I supped alone in a tavern [59] I remembered Onegin, thought about it, and began to find her idea not impossible; then it gripped me, and before I had finished my meal I had come to a decision. -

5-2019 Vocal, Ol-Z

78 rpm VOCAL RECORDS MAGDA OLIVERO [s] 3575. 12” Green Cetra BB 25028 [2-70330-II/2-70331-II]. ADRIANA LECOUVREUR: Io sono l’umile ancella / ADRIANA LECOUVREUR: Poveri fiori gemme (Cilèa). Just about 1-2. $35.00. MARIA OLSZEWSKA [c] 2470. 12” Red acous. Polydor 72778 [753av/882av]. TRAUME / SCHMERZEN (Wagner, from Wesendonck Lieder). Gleaming mint copy. Just about 1-2. $35.00. 2413. 12” Red acous. Polydor 72778 [753av/882av]. Same as preceding listing [#2470]. Few lightest superficial mks., cons. 2. $30.00. AUGUSTA OLTRABELLA [s] 3073. 12” Italian Gram. DB 2828 [2BA1204-II/2BA1205-I] IL DIBUK: Eccoti, bellal amica / IL DIBUK: Ma ora torno mverso l’anima tua (Rocca). With GINO DEL SIGNORE [t]. Orch. dir. Giuseppe Antonicelli. Just about 1-2. $12.00. COLIN O’MORE [t] 1475. 10” Brown Shellec Vocalion 24031 [9503/ ? ]. WERTHER: Pourquoi me réveiller / MANON: Le rêve (both Massenet). Just about 1-2. $8.00. SIGRID ONEGIN [c] 1322. 10” Purple acous. Brunswick 10118 [12157/12013]. VAGGVISA (ar. Raucheisen) / HERDEGOSSEN (Berg). Side one piano acc. Michael Raucheisen. Side two with orch. Just about 1-2. $8.00. 1677. 10” Purple acous. Brunswick 10132 [ ? / ? ]. DER LINDENBAUM (Schubert) / ES IST BESTIMMT IN GOTTES RATH (Mendelssohn). Just about 1-2. $8.00. 3173. 12” Red Schall. Grammophon 72714 (043336/043337) [1462s/1461s]. SAPPHISCHE ODE (Brahms) / DER KREUZZUG (Schubert). Piano acc. In absolutely top condition. Just about 1-2. $25.00. 2643. 12” Red Scroll “Z”-type shellac Victor 7320 [CLR5799- II/CLR5800-I]. SAMSON ET DALILA: Printemps qui commence/ SAMSON ET DALILA: Mon coeur (Saint- Saëns).