Bill Stone in the Abyss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public in Ven Tions and in Ter Ven Tions

Public Inven tions and Inter ven tions Public Inventions and Interventions PART 2: Public Phenom e na November 10 - 28, 2000. Opening service: November 10, 5-9 pm. Blackstone Bicycle Works / monk parakeet / Dan Pe ter man Michael Blum Chemi Rosado Seijo Biotic Baking Brigade The Stockyard Institute / kids from the Back of the Yards / Jim Duignan Collectivo Cambalache Reverend Billy Eco Vida N55 REPOhistory Ultra-red (a project for our toll free line: 1-800-731-4973) Jorge Rivera Reclaim The Streets Elyce Semenec Paul Chan Urban Exploration - Infi ltration and Jinx Magazine Temporary Services Temporary Services 202 S. State Street, Suite 1124 Chicago, IL 60604 www.temporaryservices.org Front Cover: Jorge Rivera's Paracaídas - 200 parachutes thrown out over a square in San Juan Back Cover: Found photo of children playing with a discarded tire. From the Temporary Ser- vices Public Phenomena Archive Public Inventions and Inter ven tions This is a two-part exhibition looking at a broad range of practices, defi nitions, theories and uses of what is called "public space". Urban ecology, humorous activism, radical art projects, strange private expressions in public spaces and many more things will be presented along side each other mapping out a vastly complex political and social continuum that makes working in public so engaging. Part 1 - 3 Acres on the Lake: DuSable Park Proposal Project by Laurie Palmer, October 20 - November 3, 2000. Laurie Palmer has long been interested in an undeveloped 3-acre parcel of landfi ll that juts out into Lake Michigan near Navy Pier. A debate is raging right now over the future of this land, now an overgrown meadow. -

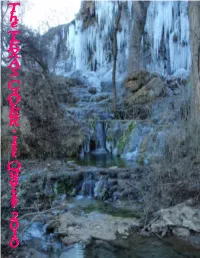

The Texas Caver, 1St Quarter 2010, Website Version, Compressed.Pub

Photo Credits: The TEXAS CAVER January — March - Vol. 56, Number 1 Front Cover— A rather frozen Gorman Falls. Project weekend and TSA Winter Business Meeting at The Texas Caver is a quarterly publication of the Texas Colorado Bend State Park, Sunday, January 10th. Speleological Association (TSA), an internal Photo by Andy Zenker. organization of the National Speleological Society . All material copyrighted 2010 by the Texas Speleological Back Inside Cover — A montage of photos of Gorman Association, unless otherwise stated. Falls. Top and lower left by Allan Cobb. Lower right by Andy Zenker. Subscriptions are included with TSA membership, which is $15/year for students, $20/year for individuals Back Cover — The view from Gerardo’s property near and $30/year for families. Laguna de Sanchez. Photo by Dale Barnard. Trip report on page 2. Libraries, institutions, and out-of-state subscribers may receive The Texas Caver for $20/year. Student subscriptions are $15/year. 2010 Texas Speleological Submissions, correspondence, and corrections should Association Officers be sent to the Editor: The TEXAS CAVER Chair: Mark Alman c/o Mark Alman [email protected] 1312 Paula Lane, Mesquite, TX 75149 [email protected] Vice-Chair: Ellie Thoene Subscriptions, dues, payments for ads, and [email protected] membership info should be sent to the TSA: Secretary: Denise Prendergast The Texas Speleological Association Post Office Box 8026 [email protected] Austin, TX 78713-8026 www.cavetexas.org Treasurer: Darla Bishop The opinions and methods [email protected] expressed in this publication are solely those of the respective authors, Publications Committee Chairman - and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editor, the TSA, or the NSS. -

January 2021

January 2021 Tim H. recommends: Upload (2020– television series) From rottentomatoes.com: From Emmy-Award winning writer Greg Daniels (The Office, Parks and Recreation) comes Upload, a new sci-fi comedy series set in a technologically advanced future where hologram phones, 3D food printers and automated grocery stores are the norm. Most uniquely, humans can choose to be "uploaded" into a virtual afterlife when they find themselves near-death. The se- ries follows a young app developer, Nathan Brown (Robbie Amell), who winds up in the hospital following a self-driving car accident, needing to quickly decide his fate. After a rushed deliberation with his shallow girlfriend Ingrid (Allegra Ed- wards), he chooses to be uploaded to her family's luxurious virtual afterlife, the Horizen company's "Lakeview." Once uploaded in Lakeview, Nathan meets his cus- tomer service "Angel" Nora Anthony (Andy Allo), who at first is his charismatic concierge and guide, but quickly becomes his friend and confidante, helping him navigate this new digital extension of life. Comedy -and- Leverage (2008-2012 television series) A drama about a team of high-tech Robin Hoods who scam greedy corporations and corrupt forces that have victimized average citizens. A sly former insurance sleuth captains the crack crew, which includes an eccentric expert thief; a comput- er virtuoso; a hardfisted "retrieval specialist"; and a grifter with ace thespian skills. Thriller Keara B. recommends: Homebody: A Guide to Creating Spaces You Never Want To Leave by Joanna Gaines From amazon.com: In Homebody: A Guide to Creating Spaces You Never Want to Leave, Joanna Gaines walks you through how to create a home that reflects the personalities and stories of the people who live there. -

Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of Ve Erything

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of vE erything R. Joshua Scannell The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2571 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of Everything by R. Joshua Scannell A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 i © 2018 R. Joshua Scannell All Rights Reserved ii Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of Everything by R. Joshua Scannell This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Patricia Ticineto Clough Chair of Examining Committee ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Victoria Pitts-Taylor, Department of Sociology Michael Jacobson, CUNY Institute for State and Local Governance Jasbir K. Puar, Department of Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers University The City University of New York iii ABSTRACT Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of Everything Author: R. Joshua Scannell Advisor: Patricia T. -

Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film Alex

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Surfing the Interzones: Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film Alex McAulay A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Pamela Cooper María DeGuzmán Kimball King Julius Raper Linda Wagner-Martin © 2008 Alex McAulay ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ALEX MCAULAY: Surfing the Interzones: Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film (Under the direction of Pamela Cooper) This dissertation presents an analysis of posthuman texts through a discussion of posthuman landscapes, bodies, and communities in literature and film. In the introduction, I explore and situate the relatively recent term "posthuman" in relation to definitions proposed by other theorists, including N. Katherine Hayles, Donna Haraway, Judith Halberstam and Ira Livingston, Hans Moravec, Max More, and Francis Fukuyama. I position the posthuman as being primarily celebratory about the collapse of restrictive human boundaries such as gender and race, yet also containing within it more disturbing elements of the uncanny and apocalyptic. My project deals primarily with hybrid texts, in which the posthuman intersects and overlaps with other posts, including postmodernism and postcolonialism. In the first chapter, I examine the novels comprising J.G. Ballard's disaster series, and apply Bakhtin's theories of hybridization, and Deleuze and Guattari's notions of voyagings, becomings, and bodies without organs to delineate the elements that constitute a posthuman landscape. -

Liminality in Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere and American Gods Courtney Linn Firman Bucknell University

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Master’s Theses Student Theses 2010 Fantasy Making the Invisible Visible: Liminality in Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere and American Gods Courtney Linn Firman Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/masters_theses Recommended Citation Firman, Courtney Linn, "Fantasy Making the Invisible Visible: Liminality in Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere and American Gods" (2010). Master’s Theses. 27. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/masters_theses/27 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master’s Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I, Courtney L. Firman, do grant permission for my thesis to be copied. i Acknowledgements I would like to, first, thank my committee for all of their input and support. Prof. Jean Peterson, Prof. Alf Siewers, and Prof. James Peterson have been indispensible throughout this process. Second, I would like to thank my entire family (especially Logan and Nicole). Without their love, support, and understanding there is no way I could have reached this goal. ii Table of Contents Introduction p. 1 Chap. 1 : The Invisible in Literature: The Voice of the Liminal in Neverwhere p. 5 and American Gods Chap. 2 : The Beast in the Sewer: Representing the Liminal for Two Millenia p. 27 Chap. 3 : Revealing the Invisible: Gaiman’s Use of the Beast in the Sewer p. 41 Conclusion p. 54 Works Cited p. 56 iii Abstract The purpose of this thesis was to examine the ways in which the fantasy genre is ideally positioned for discussing social issues, such as invisibility and liminality. -

The Northeastern Caver Cumulative Index (Volumes I – Xlv, 1969 – 2014)

THE NORTHEASTERN CAVER CUMULATIVE INDEX (VOLUMES I – XLV, 1969 – 2014) by Steve Higham revision 0: 12/14/14 PARTIAL LIST OF SECTIONS ARTICLE INDEX page 2 Accidents, safety, hazards, rescue page 2 Biology page 4 Book reviews page 4 Cartoons and drawings page 5 Cave description and exploration page 6 Cave lengths and lists page 16 Caving organizations, conventions, meetings page 16 Conservation, ownership, management page 18 Cover photos page 21 Equipment and techniques page 22 Geology, hydrology page 23 History page 24 Humor, poetry, fiction, creative page 27 Northeastern Caver page 28 Other page 29 People page 31 AUTHOR INDEX page 31 CAVE INDEX page 85 Connecticut page 85 Maine page 87 Massachusetts page 91 New Hampshire page 97 New Jersey page 101 New York page 101 Rhode Island page 120 Vermont page 121 Ontario page 128 Quebec page 129 The codes used in the cave index are as follows: a accident, rescue g geology/hydrology o owners, access, gating b biology h history p photograph c conservation i illustration r rumor or report d description m map x location Each entry is coded "xx-yyy", where the first two digits indicate the volume and the digits after the dash indicate the page number. "(S)" indicates that the article appears in the Speleodigest for the year of publication. Also, "(abs)" = abstract. 1 The table below shows the first page number of each issue in volumes I to XLV: ISSUE NO. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 VOL. NO. YR. OF PUB. FIRST PAGE OF ISSUE 1 1969 1 13 25 43 55 67 79 91 101 113 125 137 2 1970 1 9 17 1971 25 45 3 1972 -

LCSH Section U

U-2 (Reconnaissance aircraft) (Not Subd Geog) U.S. 31 U.S. Cleveland Post Office Building (Punta Gorda, Fla.) [TL686.L (Manufacture)] USE United States Highway 31 UF Cleveland Post Office Building (Punta Gorda, [UG1242.R4 (Military aeronautics)] U.S. 40 Fla.) UF Lockheed U-2 (Airplane) USE United States Highway 40 BT Post office buildings—Florida BT Lockheed aircraft U.S. 41 U.S. Coast Guard Light Station (Jupiter Inlet, Fla.) Reconnaissance aircraft USE United States Highway 41 USE Jupiter Inlet Light (Fla.) U-2 (Training plane) U.S. 44 U.S. Consulate Terrorist Attack, Banghāzī, Libya, 2012 USE Polikarpov U-2 (Training plane) USE United States Highway 44 USE Benghazi Consulate Attack, Banghāzī, Libya, U-2 Incident, 1960 U.S. 50 2012 BT Military intelligence USE United States Highway 50 U.S. Department of Education Building (Washington, Military reconnaissance U.S. 51 D.C.) U-Bahn-Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 51 USE Lyndon Baines Johnson Department of USE U-Bahnhof Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 52 Education Building (Washington, D.C.) U-Bahnhof Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 52 U.S. Embassy Bombing, Nairobi, Kenya, 1998 UF Kröpcke, U-Bahnhof (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 54 USE United States Embassy Bombing, Nairobi, Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) USE United States Highway 54 Kenya, 1998 U-Bahn-Station Kröpcke (Hannover, Germany) U.S. 58 (Va. and Tenn.) U.S. General Post Office (New York, N.Y.) BT Subway stations—Germany USE United States Highway 58 (Va. and Tenn.) USE James A. Farley Building (New York, N.Y.) U-Bahnhof Lohring (Bochum, Germany) U.S. -

The Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York City Free

FREE THE MOLE PEOPLE: LIFE IN THE TUNNELS BENEATH NEW YORK CITY PDF Jennifer Toth | 280 pages | 01 Oct 1995 | Chicago Review Press | 9781556522413 | English | Chicago, United States 20 Secrets About The Mole People Living In New York City's Tunnels Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Thousands of people live in the subway, railroad, and sewage tunnels that form the bowels of New York City. This book is about them, the so-called "mole people" The Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York City alone and in communities, in the frescoed waiting rooms of long-forgotten subway tunnels and in pick-axed compartments below busway platforms. It is about how and why people move underground, who they are, a Thousands of people live in the subway, railroad, and sewage tunnels that form the bowels of New York City. It is about how and why people move underground, who they are, and what they have to say about their lives and the treacherous "topside" world they've left behind. There are even the voices of young children taken down to the tunnels by parents who are determined to keep their families together, although as one tunnel dweller explains, "once you go down there, you can't be a child anymore. They are a diverse group, and they choose to live underground for many reasonssome rejecting society and its values, others reaffirming those values in what they view as purer terms, and still others seeking shelter from the harsh conditions on the streets. -

After Sundown

After Sundown by Frank Trollman and The Gaming Den August 10, 2012 Table of Contents Table of Contents2 Courier Run.................... 29 Fetch Quest .................... 30 1 After Sundown7 Reconnaissance.................. 30 1.1 After Sundown: An Introduction....... 7 Rescue Mission .................. 30 1.2 Monster Means Many Things.......... 7 Wet Work...................... 31 1.3 Things You Need To Play............ 8 3.6 Character Generation .............. 31 1.4 The Role of the MC................ 9 Characters for an Origin Story......... 31 Characters for an In Media Res story . 32 2 Terrible Places 11 The Power Fantasy................ 33 2.1 A Life in Horror: The Good and The Bad . 11 Placing Opposition................ 34 2.2 The Four Worlds ................. 11 Maya: The Dreamlands............. 12 4 Monstrous Society 35 Limbo: The Dark Reflection .......... 14 4.1 Organization of the Damned.......... 35 Mictlan: The Gloom ............... 15 4.2 Bands........................ 35 Being In Between Worlds............ 17 4.3 Syndicates..................... 35 2.3 Terrible People .................. 18 The Makhzen ................... 36 2.4 People in Horror: Extras and Luminaries . 18 The Cauchemar Communes........... 37 2.5 The Playable Types................ 18 The Covenant................... 37 Vampires...................... 18 World Crime League............... 38 Animates...................... 19 4.4 Cults......................... 38 Lycanthropes ................... 19 The Ash Walkers ................. 39 Witches...................... -

Megaichnus Igen. Nov.: Giant Paleoburrows Attributed to Extinct Cenozoic Mammals from South America

Ichnos An International Journal for Plant and Animal Traces ISSN: 1042-0940 (Print) 1563-5236 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gich20 Megaichnus igen. nov.: Giant Paleoburrows Attributed to Extinct Cenozoic Mammals from South America Renato Pereira Lopes, Heinrich Theodor Frank, Francisco Sekiguchi de Carvalho Buchmann & Felipe Caron To cite this article: Renato Pereira Lopes, Heinrich Theodor Frank, Francisco Sekiguchi de Carvalho Buchmann & Felipe Caron (2017) Megaichnus igen. nov.: Giant Paleoburrows Attributed to Extinct Cenozoic Mammals from South America, Ichnos, 24:2, 133-145, DOI: 10.1080/10420940.2016.1223654 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2016.1223654 Published online: 15 Sep 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 353 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gich20 ICHNOS 2017, VOL. 24, NO. 2, 133–145 https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2016.1223654 Megaichnus igen. nov.: Giant Paleoburrows Attributed to Extinct Cenozoic Mammals from South America Renato Pereira Lopesa, Heinrich Theodor Frankb, Francisco Sekiguchi de Carvalho Buchmannc, and Felipe Carona aUniversidade Federal do Pampa, Campus de Cacapava¸ do Sul, Cacapava¸ do Sul, Brazil; bUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Instituto de Geoci^encias, Porto Alegre, Brazil; cUniversidade Estadual Paulista, Laboratorio de Estratigrafia e Paleontologia, Campus do Litoral Paulista, S~ao Vicente, Brazil ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In the last ten years, more than 1,500 large burrows have been discovered in southern and Continental ichnology; southeastern Brazil, dug in rocks that include weathered granitic and basaltic rocks, sandstones, and Semifossorial mammals; other consolidated sediments. -

Part 7 79 Acres

www.PDHcenter.com PDHonline Course C634 www.PDHonline.org Part 7 A Proposition Alive with Problems 79 Acres 1 2 The City of New York granted the sub-surface rights of the area bounded by E. 42nd /47th Street/s and Lexington / Madison Avenue/s to the NYCRR in perpetuity for a $25K annual payment. Work on the new terminal began on August 17th 1903. On seventeen acres of the newly purchased plots, stables, warehouses, an orphanage and other structures required demolition including; • 120 houses • 3 churches • 2 hospitals Some station functions were temporarily relocated to the nearby Grand Central Palace hotel (an exhibition hall converted to a temporary terminal). For the utilities and two-level track scheme, excavation through solid rock ninety-feet deep was “…In the history of railroad building there is nothing to compare with the called for. Proceeding from east-to-west, Wilgus’ well thought out construction works at the Grand Central. It is a comparatively easy matter to dig a hole, plan would proceed in longitudinal “bites.” Even with an efficient and workable lay tracks and put up a building, but to rebuild a station under traffic, plan, construction would take ten full years to complete. Steam shovels excavated change the entire plant so that not a vestige of the old remained, keep 800 rock and earth to an average depth of forty-five feet to accommodate the trains running and handle from 75,000 to 100,000 passengers a day, was a underground facilities/infrastructure of the terminal (the suburban/lower level nd proposition alive with engineering and operating problems.