Beneath the Neon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public in Ven Tions and in Ter Ven Tions

Public Inven tions and Inter ven tions Public Inventions and Interventions PART 2: Public Phenom e na November 10 - 28, 2000. Opening service: November 10, 5-9 pm. Blackstone Bicycle Works / monk parakeet / Dan Pe ter man Michael Blum Chemi Rosado Seijo Biotic Baking Brigade The Stockyard Institute / kids from the Back of the Yards / Jim Duignan Collectivo Cambalache Reverend Billy Eco Vida N55 REPOhistory Ultra-red (a project for our toll free line: 1-800-731-4973) Jorge Rivera Reclaim The Streets Elyce Semenec Paul Chan Urban Exploration - Infi ltration and Jinx Magazine Temporary Services Temporary Services 202 S. State Street, Suite 1124 Chicago, IL 60604 www.temporaryservices.org Front Cover: Jorge Rivera's Paracaídas - 200 parachutes thrown out over a square in San Juan Back Cover: Found photo of children playing with a discarded tire. From the Temporary Ser- vices Public Phenomena Archive Public Inventions and Inter ven tions This is a two-part exhibition looking at a broad range of practices, defi nitions, theories and uses of what is called "public space". Urban ecology, humorous activism, radical art projects, strange private expressions in public spaces and many more things will be presented along side each other mapping out a vastly complex political and social continuum that makes working in public so engaging. Part 1 - 3 Acres on the Lake: DuSable Park Proposal Project by Laurie Palmer, October 20 - November 3, 2000. Laurie Palmer has long been interested in an undeveloped 3-acre parcel of landfi ll that juts out into Lake Michigan near Navy Pier. A debate is raging right now over the future of this land, now an overgrown meadow. -

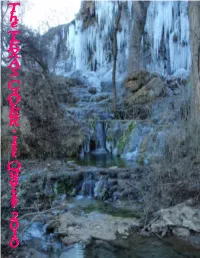

The Texas Caver, 1St Quarter 2010, Website Version, Compressed.Pub

Photo Credits: The TEXAS CAVER January — March - Vol. 56, Number 1 Front Cover— A rather frozen Gorman Falls. Project weekend and TSA Winter Business Meeting at The Texas Caver is a quarterly publication of the Texas Colorado Bend State Park, Sunday, January 10th. Speleological Association (TSA), an internal Photo by Andy Zenker. organization of the National Speleological Society . All material copyrighted 2010 by the Texas Speleological Back Inside Cover — A montage of photos of Gorman Association, unless otherwise stated. Falls. Top and lower left by Allan Cobb. Lower right by Andy Zenker. Subscriptions are included with TSA membership, which is $15/year for students, $20/year for individuals Back Cover — The view from Gerardo’s property near and $30/year for families. Laguna de Sanchez. Photo by Dale Barnard. Trip report on page 2. Libraries, institutions, and out-of-state subscribers may receive The Texas Caver for $20/year. Student subscriptions are $15/year. 2010 Texas Speleological Submissions, correspondence, and corrections should Association Officers be sent to the Editor: The TEXAS CAVER Chair: Mark Alman c/o Mark Alman [email protected] 1312 Paula Lane, Mesquite, TX 75149 [email protected] Vice-Chair: Ellie Thoene Subscriptions, dues, payments for ads, and [email protected] membership info should be sent to the TSA: Secretary: Denise Prendergast The Texas Speleological Association Post Office Box 8026 [email protected] Austin, TX 78713-8026 www.cavetexas.org Treasurer: Darla Bishop The opinions and methods [email protected] expressed in this publication are solely those of the respective authors, Publications Committee Chairman - and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editor, the TSA, or the NSS. -

January 2021

January 2021 Tim H. recommends: Upload (2020– television series) From rottentomatoes.com: From Emmy-Award winning writer Greg Daniels (The Office, Parks and Recreation) comes Upload, a new sci-fi comedy series set in a technologically advanced future where hologram phones, 3D food printers and automated grocery stores are the norm. Most uniquely, humans can choose to be "uploaded" into a virtual afterlife when they find themselves near-death. The se- ries follows a young app developer, Nathan Brown (Robbie Amell), who winds up in the hospital following a self-driving car accident, needing to quickly decide his fate. After a rushed deliberation with his shallow girlfriend Ingrid (Allegra Ed- wards), he chooses to be uploaded to her family's luxurious virtual afterlife, the Horizen company's "Lakeview." Once uploaded in Lakeview, Nathan meets his cus- tomer service "Angel" Nora Anthony (Andy Allo), who at first is his charismatic concierge and guide, but quickly becomes his friend and confidante, helping him navigate this new digital extension of life. Comedy -and- Leverage (2008-2012 television series) A drama about a team of high-tech Robin Hoods who scam greedy corporations and corrupt forces that have victimized average citizens. A sly former insurance sleuth captains the crack crew, which includes an eccentric expert thief; a comput- er virtuoso; a hardfisted "retrieval specialist"; and a grifter with ace thespian skills. Thriller Keara B. recommends: Homebody: A Guide to Creating Spaces You Never Want To Leave by Joanna Gaines From amazon.com: In Homebody: A Guide to Creating Spaces You Never Want to Leave, Joanna Gaines walks you through how to create a home that reflects the personalities and stories of the people who live there. -

Homeowner Guide to Spiders Around the Home and Yard

HOMEOWNER Guide to by Edward John Bechinski, Dennis J. Schotzko, and Craig R. Baird BUL 871 Spiders around the home and yard “Even the two potentially most harmful spiders – the black widow and the hobo spider – rarely injure people in Idaho.” TABLE OF CONTENTS QUICK GUIDE TO COMMON SPIDERS . .4 PART 1 SPIDER PRIMER . .6 Basic external body structure . .6 Spider biology & behavior . .7 Spider bites . .8 PART 2 COMMONLY ENCOUNTERED SPIDERS . .10 Web-spinning spider •funnel-web weavers . .11 •orb weavers . .11 •sheet-web spiders . .12 •cellar spiders . .12 •cobweb weavers . .13 Spiders that do not spin webs Active hunters •jumping spiders . .14 Lie-and-wait ambush hunter •trapdoor spider . .15 •crab spiders . .15 •wolf spiders . .16 •tarantulas . .17 Daddy longlegs . .17 PART 3 POISONOUS SPIDERS IN IDAHO . .18 •western black widow . .18 •hobo spider . .20 •yellow sac spider . .22 •brown recluse spider . .22 PART 4 DEALING WITH SPIDERS AROUND THE HOME . .24 MYTHS ABOUT SPIDERS #1 A sleeping person swallows eight spiders per year . .9 #2 Daddy longlegs are the most poisonous spiders known . .18 #3 Widow-makers . .20 #4 Hobos are the spiders with “boxing gloves” . .21 #5 Hobo spiders are unusually aggressive . .22 Spiders around the home and yard 3 QUICK GUIDE TO COMMON SPIDERS IN IDAHO Note: spiders are shown as typical life-size adults; immatures will be smaller Spiders on webs If web looks like a . and the web is located . and the spider looks like . then it might be . vertical bull’s-eye of concentric outside under the eaves OR orb weaver rings between landscape plants see page 11 30 mm flat trampoline that narrows into a outside on evergreen shrubs and funnel-web weaver funnel rock gardens OR inside the corners see page 11 of basements and garages 40 mm messy cobweb inside garage, shed, basement, cellar spider crawlspace OR outside under decks see page 12 OR 40 mm cobweb weaver 10 mm see page 13 thin, small oval purse outside within a rolled-up leaf OR sac spider inside along ceiling and wall 8 mm see page 22 Spiders NOT on webs If the spider is . -

PLS 116 How to Identify Or Misidentify the Hobo Spider

PLS 116 How to identify (or misidentify) the hobo spider Rick Vetter and Art Antonelli Since the late 1980s, many people in Washington have been concerned about the hobo spider because it has been blamed as the cause of dermatologic wounds. We offer here a guide to help identify some medium-sized Washington spiders found in homes. However, keep in mind that without a microscope you may not be able to identify hobo spiders and may have to settle for determining that your spider is NOT a hobo spider. This may be frustrating and not the goal you had in mind, however, quite often the question is not "What spider do I have?" but "Do I have a hobo spider?" You should be able to learn enough to eliminate many spiders from consideration without a microscope and sometimes with just the naked eye. Most people want a world with simple black/white answers but you must realize that there many shades of gray in between and this is the reality of spider identification. This publication was initiated discriminatory skills up a notch, with because there is no currently a little practice, you should be able to available guide to spider confidently determine the identification for the person with characteristics of spiders that are limited arachnological skills. Most of NOT hobo spiders, which will be the the previous guides for hobo spider majority of the medium-sized spiders identification try to give a simplistic you will encounter. way to discern hobo spiders. We have found that many well- intentioned people misconstrue the information and confidently misidentify their non-hobo spider as a hobo. -

The Strip: Las Vegas and the Symbolic Destruction of Spectacle

The Strip: Las Vegas and the Symbolic Destruction of Spectacle By Stefan Johannes Al A dissertation submitted in the partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor Greig Crysler Professor Ananya Roy Professor Michael Southworth Fall 2010 The Strip: Las Vegas and the Symbolic Destruction of Spectacle © 2010 by Stefan Johannes Al Abstract The Strip: Las Vegas and the Symbolic Destruction of Spectacle by Stefan Johannes Al Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Over the past 70 years, various actors have dramatically reconfigured the Las Vegas Strip in many forms. I claim that behind the Strip’s “reinventions” lies a process of symbolic destruction. Since resorts distinguish themselves symbolically, each new round of capital accumulation relies on the destruction of symbolic capital of existing resorts. A new resort either ups the language within a paradigm, or causes a paradigm shift, which devalues the previous resorts even further. This is why, in the context of the Strip, buildings have such a short lifespan. This dissertation is chronologically structured around the four building booms of new resort construction that occurred on the Strip. Historically, there are periodic waves of new casino resort constructions with continuous upgrades and renovation projects in between. They have been successively theorized as suburbanization, corporatization, Disneyfication, and global branding. Each building boom either conforms to a single paradigm or witnesses a paradigm shift halfway: these paradigms have been theorized as Wild West, Los Angeles Cool, Pop City, Corporate Modern, Disneyland, Sim City, and Starchitecture. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 02-04-1910 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 2-4-1910 Santa Fe New Mexican, 02-04-1910 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 02-04-1910." (1910). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/132 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 6 SANTA FE NEW MEXICAN' "32zziziiiiiiiiiiiiiii 4 rzzzizizizzzz!mTzz VOL. 46 12 PAGES SANTA NEW MEXICO. FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 4. 1910 12 PAGES NO 304 mif suns m STEAMER KENtUGKYilNQUIRY UG jPARiS CLEANER HE COURT Bl ; BUT s sinking; is postponed than before EST GAT ON WRECKED Robert J. Rosenfeld Recovers Wireless Messages Picked There Was Some Resistance Example of What Thorough Officials of Federal Govern- - With Remnants of It Paulhan i Big Judgment Against Min- Up Telling of Vessel's to This Move but the Ma Disinfection and Sanitary ment Arrive at Primero Started Taday for New ing Company Bad Plight jority Prevailed Work Can Accomplish for Purpose Orleans SMALLPOX AT LOS PINOS IN STORM OFF HATTERAS SURGEON GENERAL FOR NAVY FOREIGN RELIEF $1,000,000 SIXTEEN FUNERALS TODAY KIAY VISIT DALLAS AND HOUSTON Three Companies Filed Incor- Louisiana and Other Boats Hast- Bill to Quiet Title to Refugio In Appearance the City Is Now Almost Impassable Obstructions Made His Record Flight in poration Papers in Secretary's ening to Assist Doomed Ship Colony Grant Is Intro Approaching the Normal Continue to be Encountered Machine That Was Crumbled Office. -

Wyoming Road Trip WESTERN HERITAGE ALONG OUR SCENIC BYWAYS

Wyoming Road Trip WESTERN HERITAGE ALONG OUR SCENIC BYWAYS WYOMINGTOURISM.ORG ~ 800-225-5996 A | B | C | D | E | F | G | 8 22 1 1 2 7 2 6 3 18 NORTHWEST 3 20 4 4 5 17 5 21 6 13 7 9 SOUTHWEST 8 11 9 12 15 10 14 | H | I | J yoming’s scenic byways offer the visitor a Wspectacular choice of routes. Views range from snow-capped peaks and alpine plateaus to wide grassland vistas. Many Wyoming roads wind through beautiful National Forests and each scenic byway passes through an area with its own unique beauty and history so don’t forget to stop the car, get out and explore a little further. Wyoming’s fresh air, wildflowers, and mountain pines are best experienced up close and personal. NORTHWEST 1. Beartooth Scenic Byway (B,1) ...................... 2-3 19 2. Chief Joseph Scenic Byway (C,1).................... 4-5 3. Buffalo Bill Cody Scenic Byway (C,2) ................ 6-7 4. Wind River Canyon Scenic Byway (D,4) .............8-10 5. Wyoming Centennial Scenic Byway (B,4) ........... 11-13 NORTHEAST 6. Red Gulch/Alkali Scenic Backway (D,4) ............ 14-15 7. Big Horn Scenic Byway (F,2) .....................16-17 8. Medicine Wheel Passage (E,1) ................... 18-19 SOUTHWEST 9. Big Spring Scenic Backway (A,7) ................. 20-21 10. Mirror Lake Scenic Byway (A,9) .................. 22-23 11. Muddy Creek Historic Backway Bridger Valley Historic Byway (B,9) ............... 24-25 12. Flaming Gorge/Green River Scenic Byway (D,9) ...... 26-27 SOUTHEAST 13. Seminoe-Alcova Backway (F,7) ................... 28-29 16 14. -

Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of Ve Erything

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of vE erything R. Joshua Scannell The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2571 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of Everything by R. Joshua Scannell A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 i © 2018 R. Joshua Scannell All Rights Reserved ii Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of Everything by R. Joshua Scannell This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Patricia Ticineto Clough Chair of Examining Committee ______________________ __________________________________________ Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Victoria Pitts-Taylor, Department of Sociology Michael Jacobson, CUNY Institute for State and Local Governance Jasbir K. Puar, Department of Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers University The City University of New York iii ABSTRACT Electric Light: Automating the Carceral State During the Quantification of Everything Author: R. Joshua Scannell Advisor: Patricia T. -

The Metal Resources of New Mexico and Their Economic Features Through 1954

BULLETIN 39 The Metal Resources of New Mexico and Their Economic Features Through 1954 A revision of Bulletin 7, by Lasky and Wootton, with detailed information for the years 1932-1954 BY EUGENE CARTER ANDERSON 1957 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY CAMPUS STATION SOCORRO, NEW MEXICO NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING & TECHNOLOGY E. J. Workman, President STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES Alvin J. Thompson, Director THE REGENTS MEMBERS EX OFFICIO THE HONORABLE EDWIN L. MECHEM………...Governor of New Mexico MRS. GEORGIA L. LUSK ......................Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTED MEMBERS ROBERT W. BOTTS ....................................................................Albuquerque HOLM O. BURSUM, JR. .....................................................................Socorro THOMAS M. CRAMER .................................................................... Carlsbad JOHN N. MATHEWS, JR. ...................................................................Socorro RICHARD A. MATUSZESKI ......................................................Albuquerque Contents Page INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Scope of Bulletin ..................................................................................... 1 Other Reports Dealing With the Geology and Mineral Resources of New Mexico ...................................................................................................... -

Las Vegas Optic, 06-21-1909 the Optic Publishing Co

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Las Vegas Daily Optic, 1896-1907 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-21-1909 Las Vegas Optic, 06-21-1909 The Optic Publishing Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lvdo_news Recommended Citation The Optic Publishing Co.. "Las Vegas Optic, 06-21-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lvdo_news/2698 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Las Vegas Daily Optic, 1896-1907 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL. XXXJ NO. 198 EAST LAS VEGAS, NEW. MEXICO, MONDAY, JUNE 21, 1909 FIVE O'CLOCK EDITION)- - 1MAC KILLS PABLO SAFE TAPPED MURDERER SURPRISE IN ISTRIAL II ARELLANES, WEALTHY ON WEST EVADES GOULD CALHOUN ORA STOCKMA SIDE POLICE CASE CASE .v.. , .. SMOOTH PIECE OF WORK AT H. 0. CHINAMAN SUSPECTED OF SLAY DEFENSE RESTS UNEXPECTEDLY, JURY STOOD TEN FOR ACqVjIT. BROWN TRADING ING MISSIONARY DROPS OUT . TAKING UNA-- CON. Attacks Him While He t PLAINTIFF . TAL AND TWO FOR is ; Working ' OF SIGHT - -- f WARES VICTION Alone in Field, Braining Him With JaggecL Rock and Beating His Head to CONSIDERABLt HAUL MADE IMPORTANT WITNESS HELD ENOUGH EVIDENCE' ALHEADY mnRY fah iifffnmt a -- After r '. Jelly Captured Desperate right BURGLARS SECURE $25 IN MONEY RESTAURANT PROPRIETOR WHO COUNSEL FOR HUSBAND SAYS HE SORELY DISAPPOINTED, HOWEV-- , - AND GOLD WATCH VAL- . , WAS'SUITOR OF VICTIM IS HAS SHOWN DESERTION WAS ER. FOR HE EXPECTED AN - Mora, N. -

Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film Alex

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Surfing the Interzones: Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film Alex McAulay A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Pamela Cooper María DeGuzmán Kimball King Julius Raper Linda Wagner-Martin © 2008 Alex McAulay ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ALEX MCAULAY: Surfing the Interzones: Posthuman Geographies in Twentieth Century Literature and Film (Under the direction of Pamela Cooper) This dissertation presents an analysis of posthuman texts through a discussion of posthuman landscapes, bodies, and communities in literature and film. In the introduction, I explore and situate the relatively recent term "posthuman" in relation to definitions proposed by other theorists, including N. Katherine Hayles, Donna Haraway, Judith Halberstam and Ira Livingston, Hans Moravec, Max More, and Francis Fukuyama. I position the posthuman as being primarily celebratory about the collapse of restrictive human boundaries such as gender and race, yet also containing within it more disturbing elements of the uncanny and apocalyptic. My project deals primarily with hybrid texts, in which the posthuman intersects and overlaps with other posts, including postmodernism and postcolonialism. In the first chapter, I examine the novels comprising J.G. Ballard's disaster series, and apply Bakhtin's theories of hybridization, and Deleuze and Guattari's notions of voyagings, becomings, and bodies without organs to delineate the elements that constitute a posthuman landscape.