Including Claude Mckay in the Secondary-Level Classroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

HARLEM in SHAKESPEARE and SHAKESPEARE in HARLEM: the SONNETS of CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, and GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2015 HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS David J. Leitner Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Leitner, David J., "HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 1012. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS by David Leitner B.A., University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, 1999 M.A., Southern Illinois University Carbondale, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Department of English in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2015 DISSERTATION APPROVAL HARLEM IN SHAKESPEARE AND SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM: THE SONNETS OF CLAUDE MCKAY, COUNTEE CULLEN, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND GWENDOLYN BROOKS By David Leitner A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Approved by: Edward Brunner, Chair Robert Fox Mary Ellen Lamb Novotny Lawrence Ryan Netzley Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 10, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF DAVID LEITNER, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in ENGLISH, presented on April 10, 2015, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Final November 2005 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Summary Statement 1 Bac.ground and Purpose 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 National Persp4l<live 5 1'k"Y v. f~u,on' World War I: 1896-1917 5 World W~r I and Postw~r ( r.: 1!1t7' EarIV 1920,; 8 Tulsa RaCR Riot 14 IIa<kground 14 TI\oe R~~ Riot 18 AIt. rmath 29 Socilot Political, lind Economic Impa<tsJRamlt;catlon, 32 INVENTORY 39 Survey Arf!a 39 Historic Greenwood Area 39 Anla Oubi" of HiOlorK G_nwood 40 The Tulsa Race Riot Maps 43 Slirvey Area Historic Resources 43 HI STORIC GREENWOOD AREA RESOURCeS 7J EVALUATION Of NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 91 Criteria for National Significance 91 Nalional Signifiunce EV;1lu;1tio.n 92 NMiol\ill Sionlflcao<e An.aIYS;s 92 Inl~ri ly E~alualion AnalY'is 95 {"",Iu,ion 98 Potenl l~1 M~na~menl Strategies for Resource Prote<tion 99 PREPARERS AND CONSULTANTS 103 BIBUOGRAPHY 105 APPENDIX A, Inventory of Elltant Cultural Resoun:es Associated with 1921 Tulsa Race Riot That Are Located Outside of Historic Greenwood Area 109 Maps 49 The African American S«tion. 1921 51 TI\oe Seed. of c..taotrophe 53 T.... Riot Erupt! SS ~I,.,t Blood 57 NiOhl Fiohlino 59 rM Inva.ion 01 iliad. TIll ... 61 TM fighl for Standp''''' Hill 63 W.II of fire 65 Arri~.. , of the Statl! Troop< 6 7 Fil'lal FiOlrtino ~nd M~,,;~I I.IIw 69 jii INTRODUCTION Summary Statement n~sed in its history. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

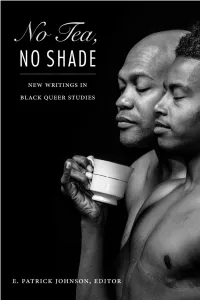

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

THE POLITICAL THOUGHT of the THIRD WORLD LEFT in POST-WAR AMERICA a Dissertation Submitted

LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Washington, DC August 6, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Benjamin Feldman All Rights Reserved ii LIBERATION FROM THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY: THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE THIRD WORLD LEFT IN POST-WAR AMERICA Benjamin Feldman, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the full intellectual history of the Third World Turn: when theorists and activists in the United States began to look to liberation movements within the colonized and formerly colonized nations of the ‘Third World’ in search of models for political, social, and cultural transformation. I argue that, understood as a critique of the limits of New Deal liberalism rather than just as an offshoot of New Left radicalism, Third Worldism must be placed at the center of the history of the post-war American Left. Rooting the Third World Turn in the work of theorists active in the 1940s, including the economists Paul Sweezy and Paul Baran, the writer Harold Cruse, and the Detroit organizers James and Grace Lee Boggs, my work moves beyond simple binaries of violence vs. non-violence, revolution vs. reform, and utopianism vs. realism, while throwing the political development of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and the Third World Women’s Alliance into sharper relief. -

Introduction 1

Notes Introduction 1 . Similar attempts to link poetry to immediate political occasions have been made by Mark van Wienen in Partisans and Poets: The Political Work of American Poetry in the Great War and by John Marsh’s anthology You Work Tomorrow . See also Nancy Berke’s Women Poets on the Left and John Lowney’s History, Memory, and the Literary Left: Modern American Poetry, 1935–1968 . 2 . Jos é E. Lim ó n discusses the “mixture of poetry and politics” that informed the Chicano movements of the 1960s and 1970s (81). On Vietnam antiwar poetry, see Bibby. There are, of course, countless studies of individual authors that trace their relationships to politics and social movements. I incorporate the relevant studies throughout the chapters. 3 . In analogy to Wallerstein’s model, the literary world has been conceptualized as a largely autonomous cultural space constituted by power struggles between centers, semi-peripheries, and peripheries, most prominently by Franco Moretti and Pascale Casanova (cf. Moretti; Casanova). But since Wallerstein insists that the world-system is concerned with world-economies (global capitalism) and world-empires (nation-states aiming for geopolitical dominance), systems, that is, which cut across cultural and institutional zones, it seems more plausible to posit the modern world-system as the historical horizon of textual production and interpretation. One of the first uses of world-systems analysis for a concep- tualization of postmodernity and postmodern art was Fredric Jameson’s essay “Culture and Finance Capital” ( Cultural Turn 136–61). 4 . Ramazani remains elusive about the extraliterary reference of these poets’ imagination. -

11Th Week of April 27Th, 2020 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 ELA Read

Christina School District Instructional Board Grade Level: 11th Week of April 27th, 2020 Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 ELA Read the two quotes Read the poem Read the poem Complete the Short- The poem “If We Must below. Explain what “My City” by James “If We Must Die” by Written Response 16 Die” is considered an each means in your Weldon Johnson and Claude McKay and and 17. English, or own words and then answer the questions answer the questions Shakespearean. The explain how each 1-7. 8-15. sonnet has a rhyme resonates with you scheme of abab cdcd and/or your life. efef gg. This divides --------------------------- the poem into four “The world does not distinct line groups: know that a people three quatrains, or is great until that four-line units, people produces followed by a couplet, great literature and a pair of rhymed lines. art.” —James Weldon Write your own Johnson English Sonnet and --------------------------- title it My City. It can “If a man is not be about where you faithful to his own live now or a city you individuality, he would like to visit. cannot be loyal to anything.” —Claude McKay --------------------------- Read the background information on James Weldon Johnson and Claude Christina School District Instructional Board McKay. Underline 2 important details for each. Math Properties of Complete Properties of Complete Properties of Complete Properties of Complete Properties of (IM3) Logarithms Logarithms Worksheet 2 Logarithms Worksheet 2 Logarithms Worksheet 3 Logarithms Worksheet 4 #1-13. (attached) #14-26. (attached) #1-9. (attached) #1-5. -

Teacher Kit Unit 3 GRACE ABOUNDING the Core Knowledge Anthology of African-American Literature, Music, and Art Please Read

GRACE ABOUNDING The Core Knowledge Anthology of African-American Literature, Music, and Art Teacher Kit Unit 3 GRACE ABOUNDING The Core Knowledge Anthology of African-American Literature, Music, and Art Please Read Editor’s Note About the Teacher Resource Kits For each of the four major literary units in Grace Abounding there is a corresponding Teacher Resource Kit, which includes Lesson Plans, Reading Check Tests, Vocabulary Tests, and answer keys. Please fi nd the forementioned sections in the bookmark tab of your Teacher Resource Kit PDF. Copyright Information. Th e purchase of a Grace Abounding Teacher Kit grants to the teacher (Purchaser) the right to reprint materials as needed for use in the classroom. For instance, Student Handouts and other assessments may be reproduced as needed by Purchasers for use in the classroom or as homework assignments. Materials in the Teacher Kits may not be reproduced for commercial purposes and may not be reproduced or distributed for any other use outside of the Purchaser’s classroom without written consent from the Core Knowledge Foundation. Lesson Plans With the lesson plans, teachers can target major language arts objectives while giving students exposure to important African-American writers, thinkers, and activists. Th e fi rst page of each lesson plan is for the teacher’s reference only and should be used in planning for a day’s lesson. Th e fi rst page usually includes basic information about the lesson (e.g., objectives, time allotment, and content), a “mini-lesson” that contains basic information and terminology the students should know as well as examples for the teacher to write on the board and use as the basis of discussion and instruction. -

Vol. 40, No. 6, Jul, 1995

NEWS & LETTERS Theory/Practice 'Human Power is its own end'—Marx Vol. 40 - No. 6 JULY 1995 250 Chinatown a Supreme Court opens new racist era J.S. labor by Michelle Landau The U.S. Supreme Court closed out its 1994-95 term in June with a sweeping, retrograde attack on Black jattlefront America, whose effects will be felt for years to come. The Court ruled against the legality of federal mandates for by John Marcotte affirmative action; against efforts to improve the quality It is a long distance from the Midwest farm country of education in segregated inner-city Black schools; and iround Decatur, 111., where Staley, Caterpillar and Fire against initiatives that had succeeded in translating mi stone workers have been on strike or locked out, to New nority group voting rights into voting power. fork City's Chinatown. It is a distance of a thousand All three decisions (by the same 5-4 majority of Jus niles, and of language and culture. tices Rehnquist, Kennedy, Scalia, O'Connor, and Thom But Chinatown is every bit as much a war zone as De- as) represent reversals from the one period in the :atur, and if the Chinese restaurant, garment and con- Court's existence when it responded to the progressive itruction workers could meet the struggling workers thrust of American history, the mid-1950s through the rom Staley and Cat and Firestone, I don't think lan- mid-1970s. All three decisions proclaim a "color-blind so fuage would be a big problem between them. They ciety," and insidiously use the 1950s-60s language of vould speak the same language, the language of freedom equality and civil rights to reduce the meaning of rom slave labor. -

If We Must Die

summary This poem is a defiant call to protest. The speaker warns against passive acceptance of hostility and urges people to fight back. He suggests that death is inevitable but can be noble if it serves a cause. The final couplet states the speaker’s resolve to die fighting. If We Must Die Claude McKay If we must die, let it not be like hogs Hunted and penned in an inglorious1 spot, LITERARY ANALYSIS While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs, Making their mock at our accursed lot. c sonnet 5 If we must die, O let us nobly die, Possible answer: The rhyme scheme is So that our precious blood may not be shed In vain; then even the monsters we defy abab, cdcd. On the basis of this rhyme Shall be constrained2 to honor us though dead! c c SONNET scheme, the sonnet is Shakespearean. O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe! State the rhyme scheme of lines 1–8. Considering 10 Though far outnumbered let us show us brave, If students need help . Refer them to the rhyme scheme, what page 847 and the definitions of Petrarchan And for their thousand blows deal one deathblow! type of sonnet is this? and Shakespearean sonnets. What though before us lies the open grave? Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack, Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back! d d FORM AND MEANING By the end of the poem, what resolution has the READING SKILL speaker reached? d form and meaning Possible answer: The speaker decides that he will fight back even if he dies fighting.