This Fact Sheet Is Prepared by the Sons of Confederate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklah

FEDERAL REFUGEES FROM INDIAN TERRITORY, 1861-1867 By JERRY LEON GILL /( Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1967 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo~ the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1973 :;-1' ., '' J~~ /'77~' G415 f. •. &if'• .~:,; . ;.. , : - i \ . ..J ') .: • .·•.,. -~ 1•, j ( . i • • I OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OCT 8 1973 FEDERAL REFUGEES FROM IND IAN TERRITORY, 1861-1867 Thesis Approvedr cPean "of the Graduate College ii PREFACE This study is concerned with the influence of the Civil War on the Indian tribes residing in Indian Territory who chose to remain loyal to the United States government during the conflict. Emphasis is placed on the Cherokee, Cree~, Chickasaw, and Seminole Indians, but all tribes and portions of Indian Territory tribes loyal to the United States during the Civil War are included in the study. Confederate military control of Indian Territory early in the Civil War forced the Indians loyal to the United States to flee north from Indian Territory. Before the war had ended,·approximately 10,500 Feder al refugee Indians had scattered across Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, and :Mexico. The reasons why these Indians remained loyal to the United States, their exodus from Indian Territory, their exile, and their return to Indian Territory are documented and evaluated in this study. The suffering and death expe:i;ienced by these refugees are unique in Civil War history, and far surpassed the de.privation and sacrifices made by other civilian populations. Hundreds of non-combatants,. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Works

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Works Progress Administration Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ Projects Collection Compiled 1969 - Revised 2002 Works Progress Administration (WPA) Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ Project Collection. Records, 1937–1941. 23 feet. Federal project. Book-length manuscripts, research and project reports (1937–1941) and administrative records (1937–1941) generated by the WPA Historic Sites and Federal Writers’ projects for Oklahoma during the 1930s. Arranged by county and by subject, these project files reflect the WPA research and findings regarding birthplaces and homes of prominent Oklahomans, cemeteries and burial sites, churches, missions and schools, cities, towns, and post offices, ghost towns, roads and trails, stagecoaches and stage lines, and Indians of North America in Oklahoma, including agencies and reservations, treaties, tribal government centers, councils and meetings, chiefs and leaders, judicial centers, jails and prisons, stomp grounds, ceremonial rites and dances, and settlements and villages. Also included are reports regarding geographical features and regions of Oklahoma, arranged by name, including caverns, mountains, rivers, springs and prairies, ranches, ruins and antiquities, bridges, crossings and ferries, battlefields, soil and mineral conservation, state parks, and land runs. In addition, there are reports regarding biographies of prominent Oklahomans, business enterprises and industries, judicial centers, Masonic (freemason) orders, banks and banking, trading posts and stores, military posts and camps, and transcripts of interviews conducted with oil field workers regarding the petroleum industry in Oklahoma. ____________________ Oklahoma Box 1 County sites – copy of historical sites in the counties Adair through Cherokee Folder 1. Adair 2. Alfalfa 3. Atoka 4. Beaver 5. Beckham 6. -

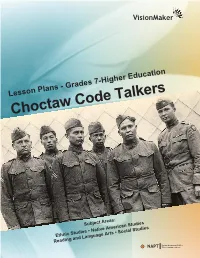

Choctaw Code Talkers

VisionMaker Lesson Plans - Grades 7-Higher Education Choctaw Code Talkers Subject Areas: Ethnic Studies • Native American Studies Reading and Language Arts • Social Studies NAPT Native American Public Telecommunications VisionMaker Procedural Notes for Educators Film Synopsis In 1918, not yet citizens of the United States, Choctaw men of the American Expeditionary Forces were asked to use their Native language as a powerful tool against the German Forces in World War I, setting a precedent for code talking as an effective military weapon and establishing them as America's original Code Talkers. A Note to Educators These lesson plans are created for students in grades 7 through higher education. Each lesson can be adapted to meet your needs. Robert S. Frazier, grandfather of Code Talker Tobias Frazier, and sheriff of Jack's Fork and Cedar Counties Image courtesy of "Choctaw Code Talkers" Native American Public 2 NAPT Telecommunications VisionMaker Objectives and Curriculum Standards a. Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, Objectives paragraph, or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) These activities are designed to give participants as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. learning experiences that will help them understand and b. Identify and correctly use patterns of word changes that indicate different meanings or parts of speech. consider the history of the sovereign Choctaw Nation c. Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., of Oklahoma, and its unique relationship to the United dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to States of America; specifically how that relates to the find the pronunciation of words, a word or determine or clarify documentary, Choctaw Code Talkers. -

This Document Is Made Available Electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library As Part of an Ongoing Digital Archiving Project

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH AND WRITINGS ON AMIIEIRIICAN IINIDIIANS RUSSELL THORNTON and MARY K. GRASMICK ~ ~" 'lPIH/:\RyrII~ F l\IHNN QlA A publication of the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, 311 Walter Library, 117 Pleasant St. S.E., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455 The content of this report is the responsibility of the authors and is not necessarily endorsed by CURA. Publication No. 79-1, 1979. Cover design by Janet Huibregtse. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 American and Ethnic Studies Journals . 3 Journals Surveyed 4 Bibliography 5 Economics Journals 13 Journals Surveyed 14 Bibliography 15 Geography Journals 17 Journals Surveyed 18 Bibliography 19 History Journals . 25 Journals Surveyed . 26 Bibliography 28 Interdisciplinary Social Science Journals .133 Journals Surveyed .134 Bibliography .135 Political Science Journals . .141 Journals Surveyed .142 Bibliography .143 Sociology Journals • .145 Journals Surveyed . .146 Bibliography .148 INTRODUCTION Social science disciplines vary widely in the extent to which they contain scholarly knowledge on American Indians. Anthropology and history contain the most knowledge pertaining to American Indians, derived from their long traditions of scholarship focusing on American Indians. The other social sciences are far behind. Consequently our social science knowledge about American Indian peoples and their concerns is not balanced but biased by the disciplinary perspectives of anthropology and history. The likelihood that American society contains little realistic knowledge about contemporary American Indians in comparison to knowledge about traditional and historical American Indians is perhaps a function of this disciplinary imbalance. -

A Critical Analysis of the Black President in Film and Television

“WELL, IT IS BECAUSE HE’S BLACK”: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BLACK PRESIDENT IN FILM AND TELEVISION Phillip Lamarr Cunningham A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2011 Committee: Dr. Angela M. Nelson, Advisor Dr. Ashutosh Sohoni Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Butterworth Dr. Susana Peña Dr. Maisha Wester © 2011 Phillip Lamarr Cunningham All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Ph.D., Advisor With the election of the United States’ first black president Barack Obama, scholars have begun to examine the myriad of ways Obama has been represented in popular culture. However, before Obama’s election, a black American president had already appeared in popular culture, especially in comedic and sci-fi/disaster films and television series. Thus far, scholars have tread lightly on fictional black presidents in popular culture; however, those who have tend to suggest that these presidents—and the apparent unimportance of their race in these films—are evidence of the post-racial nature of these texts. However, this dissertation argues the contrary. This study’s contention is that, though the black president appears in films and televisions series in which his presidency is presented as evidence of a post-racial America, he actually fails to transcend race. Instead, these black cinematic presidents reaffirm race’s primacy in American culture through consistent portrayals and continued involvement in comedies and disasters. In order to support these assertions, this study first constructs a critical history of the fears of a black presidency, tracing those fears from this nation’s formative years to the present. -

Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina David W

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 8-9-2014 Hard Rows to Hoe: Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina David W. Dangerfield University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dangerfield, D. W.(2014). Hard Rows to Hoe: Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2772 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARD ROWS TO HOE: FREE BLACK FARMERS IN ANTEBELLUM SOUTH CAROLINA by David W. Dangerfield Bachelor of Arts Erskine College, 2005 Master of Arts College of Charleston, 2009 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Mark M. Smith, Major Professor Lacy K. Ford, Committee Member Daniel C. Littlefield, Committee Member David T. Gleeson, Committee Member Lacy K. Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by David W. Dangerfield, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation and my graduate education have been both a labor and a vigil – and neither was undertaken alone. I am grateful to so many who have worked and kept watch beside me and would like to offer a few words of my sincerest appreciation to the teachers, colleagues, friends, and family who have helped me along the way. -

The Battle of Honey Springs: the Civil War Comes to Indian Territory

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 326 SO 032 673 AUTHOR Adkins, Mike; Jones, Ralph TITLE The Battle of Honey Springs: The Civil War Comes to Indian Territory. Teaching with Historic Places. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. National Register of Historic Places. PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 35p. AVAILABLE FROM Teaching with Historic Places, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Suite NC400, Washington, DC 20240. For full text: http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/68honey/68honey .htm. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Civil War (United States); *Heritage Education; *Historic Sites; History Instruction; Primary Sources; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Student Educational Objectives; Student Research IDENTIFIERS National Register of Historic Places ABSTRACT Union Army troops marched south through Indian territory on July 17, 1863, to face the Confederate Army forces in a battle that would help determine whether the Union or the Confederacy would control the West . beyond theMississippi River. The Confederate troops that these soldiers faced in the Battle of Honey Springs concealed themselves among the trees lining a nearby water source after which the battle is named. The Battle of Honey Springs was important because of its setting in what is now eastern Oklahoma and because Native Americans fought and died there for both the North and the South. This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file "Honey Springs Battlefield" and other sources. The lesson can be used to teach units on the Civil War, on Native American history, or on cultural diversity. -

1918 Journal

; 1 SUPEEME COUET OE THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 7, 1918. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day, Mr. Justice Van Devanter, Mr. Justice Pitney, Mr. Justice McReynolds, Mr. Justice Brandeis, and Mr. Justice Clarke. John Carlos Shields, of Detroit, Mich.; Willis G. Clarke, of Detroit, Mich.; J. Merrill Wright, of Pittsburgh, Pa.; David L. Starr, of Pittsburgh, Pa.; Albert G. Liddell, of Pittsburgh, Pa.; Claude R. Porter, of Centerville, Iowa; Henry F. May, of Denver, Colo. ; James H. Anderson, of Chattanooga, Tenn. ; Robert A. Hun- ter, of Shreveport, La.; J. W. Pless, of Marion, N. C. ; Stanley Moore, of Oakland, Cal. ; John Evarts Tracy, of Milwaukee, Wis.; Walter Carroll Low, of New York City; Norbert Heinsheimer, of New York City ; John R. Lazenby, of Boston, Mass. ; Frederick W. Gaines, of Toledo, Ohio; Roger Hinds, of New York City; Henry Wiley Johnson, of Savannah, Ga. ; Frederick R. Shearer, of Wash- ington, D. C. ; Walter C. Balderson, of Washington, D. C. ; Thomas M. Kirby, of Cleveland, Ohio; Arthur Mayer, of New York City; Samuel Marcus, of New York City; Kheve Henry Rosenberg, of New York City ; Isidor Kalisch, of Newark, N. J. ; Francis Lafferty, of Newark, N. J.; C. H. Henkel, of Mansfield, Ohio; Frederick A. Mohr, of Auburn, N. Y. Henry A. Brann, jr., of New York City; ; Frank Wagaman, of Hagerstown, Md. Spotswood D. Bowers, of G. ; New York City; Morris L. Johnston, of Chicago, 111.; Benjamin W. Dart, of New Orleans, La.; Maryus Jones, of Newport News, Va. -

The University of Tulsa Magazine Is Published Three Times a Year Major National Scholarships

the university of TULSmagazinea 2001 spring NIT Champions! TU’s future is in the bag. Rediscover the joys of pudding cups, juice boxes, and sandwiches . and help TU in the process. In these times of tight budgets, it can be a challenge to find ways to support worthy causes. But here’s an idea: Why not brown bag it,and pass some of the savings on to TU? I Eating out can be an unexpected drain on your finances. By packing your lunch, you can save easy dollars, save commuting time and trouble, and maybe even eat healthier, too. (And, if you still have that childhood lunch pail, you can be amazingly cool again.) I Plus, when you share your savings with TU, you make a tremendous difference.Gifts to our Annual Fund support a wide variety of needs, from purchase of new equipment to maintenance of facilities. All of these are vital to our mission. I So please consider “brown bagging it for TU.” It could be the yummiest way everto support the University. I Watch the mail for more information. For more information on the TU Annual Fund, call (918) 631-2561, or mail your contribution to The University of Tulsa Annual Fund, 600 South College Avenue, Tulsa, OK 74104-3189. Or visit our secure donor page on the TU website: www.utulsa.edu/development/giving/. the university of TULSmagazinea features departments 16 A Poet’s Perspective 2 Editor’s Note 2001 By Deanna J. Harris 3 Campus Updates spring American poet and philosopher Robert Bly is one of the giants of 20th century literature. -

William Clifton Mabry Aug

William Clifton Mabry Aug. 28, 1877-April 3, 1950 First board chairman at East Central Community College, Newton County superintendent of education, sheriff, senator, newspaper publisher, and postmaster By Kent Prince His Grandson Revised September 2019 When the family asked William Clifton Mabry about his ancestors in 1940, he dictated a history to his daughter Annie Rose, relying mainly on memory and family tradition that traced out a fairly accurate account of migration into Newton County after the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek opened up Choctaw lands. He would be amazed at the detailed history now available — not only about his great-grandfather, whose name he could not remember, but back to the man who started the family line in Virginia in the late 1600s and maybe even a couple of generations earlier in England. The most complete account of the updated information comes from Don Collins, whose book on the Mabrys has full detail on all those first generations. That work compiles the vast research by individual family members in the United States and Britain to trace the family lineage.1 Collins even coordinated a DNA project to nail the genealogy as it weaves through the many spellings of the name. Maybury is the one used by the probable ancestors in England, but as late as 1880 we find the census in Mississippi spells it Maybry in the first reference to William Clifton, then 2 years old. Using Collins, we can track William Clifton’s ancestors back to Francis Maybury who arrived in Virginia in the 1670s. There are no records on Francis’ parents, but Collins speculates he was born in the English midlands with earlier family roots in Sussex. -

Partial Bibliography

Partial Bibliography Part I: (Selected from holdings in the Honey Springs Battlefield Research Collection) Indian Territory Neighboring [& Other] Trans-Mississippi States Slavery; Abolition; African-American Soldiers; &c. Biographies & Memoirs Part II: Relevant articles from the Chronicles of Oklahoma (quarterly journal of the Oklahoma Historical Society) Indian Territory Neighboring [& Other] Trans-Mississippi States Slavery; Abolition; African-American Soldiers; &c. Biographies & Memoirs Indian Territory Able, Annie Heloise; intro. by Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green. The American Indian as Slaveholder and Secessionist. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ABison Books @, 1992; published by the Arthur Clark Co., Cleveland, Ohio, 1915; Eicher #678[a].) Abel, Annie Heloise; intro. by Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green. The American Indian in the Civil War, 1862-1865. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ABison Books @, 1992; published by The Arthur H. Clark Co., Cleveland, Ohio, 1919; Eicher #678[b].) Able, Annie Heloise; intro. by Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green The American Indian and the End of the Confederacy. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press ABison Books @, 1993; published by the Arthur Clark Co., Cleveland, Ohio, 1925; Eicher #678[c].) Agnew, Brad. Fort Gibson: Terminal on the Trail of Tears . (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979.) Anderson, Mabel Washbourne, with new material by Budd Parrish. Life of General Stand Watie, the only Indian Brigadier General of the Confederate Army and the Last to Surrender. (Harrah, Oklahoma: Brandy Station Bookshelf, 1995, facsimile reprint of 1915 volume by Mayes County Republican, with new maps.) Baird, W. David, and Danny Goble. The Story of Oklahoma. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994.) Bartels, Carolyn M.