Kansas History the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CWSAC Report Update

U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields Commonwealth of Kentucky Washington, DC October 2008 Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields Commonwealth of Kentucky U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program Washington, DC October 2008 Authority The American Battlefield Protection Program Act of 1996, as amended by the Civil War Battlefield Preservation Act of 2002 (Public Law 107-359, 111 Stat. 3016, 17 December 2002), directs the Secretary of the Interior to update the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission (CWSAC) Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields. Acknowledgments NPS Project Team Paul Hawke, Project Leader; Kathleen Madigan, Survey Coordinator; Tanya Gossett, Reporting; Lisa Rupple and Shannon Davis, Preservation Specialists; Matthew Borders, Historian; Renee S. Novak and Gweneth Langdon, Interns. Battlefield Surveyor(s) Joseph E. Brent, Mudpuppy and Waterdog, Inc. Respondents Betty Cole, Barbourville Tourist and Recreation Commission; James Cass, Camp Wildcat Preservation Foundation; Tres Seymour, Battle for the Bridge Historic Preserve/Hart County Historical Society; Frank Fitzpatrick, Middle Creek National Battlefield Foundation, Inc.; Rob Rumpke, Battle of Richmond Association; Joan House, Kentucky Department of Parks; and William A. Penn. Cover: The Louisville-Nashville Railroad Bridge over the Green River, Munfordville, Kentucky. The stone piers are original to the 1850s. The battles of Munfordville and Rowlett’s Station were waged for control of the bridge and the railroad. Photograph by Joseph Brent. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................... -

Friends of the Capitol 2009-June 2010 Report

Friends of the Capitol 2009-June 2010 Report Our Mission Statement: Friends of the Capitol is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) corporation that is devoted to maintaining and improving the beauty and grandeur of the Oklahoma State Capitol building and showcasing the magnificent gifts of art housed inside. This mission is accomplished through a partnership with private citizens wishing to leave their footprint in our state's rich history. Education and Development In 2009 and 2010 Friends of the Capitol (FOC) participated in several educational and developmental projects informing fellow Oklahomans of the beauty of the capitol and how they can participate in the continuing renovations of Oklahoma State Capitol building. In March of 2010, FOC representatives made a trip to Elk City and met with several organizations within the community and illustrated all the new renovations funded by Friends of the Capitol supporters. Additionally in 2009 FOC participated in the State Superintendent’s encyclo-media conference and in February 2010 FOC participated in the Oklahoma City Public Schools’ Professional Development Day. We had the opportunity to meet with teachers from several different communities in Oklahoma, and we were pleased to inform them about all the new restorations and how their school’s name can be engraved on a 15”x30”paver, and placed below the Capitol’s south steps in the Centennial Memorial Plaza to be admired by many generations of Oklahomans. Gratefully Acknowledging the Friends of the Capitol Board of Directors Board Members Ex-Officio Paul B. Meyer, Col. John Richard Chairman USA (Ret.) MA+ Architecture Oklahoma Department Oklahoma City of Central Services Pat Foster, Vice Chairman Suzanne Tate Jim Thorpe Association Inc. -

The Ohio National Guard Before the Militia Act of 1903

THE OHIO NATIONAL GUARD BEFORE THE MILITIA ACT OF 1903 A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Cyrus Moore August, 2015 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Cyrus Moore B.S., Ohio University, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Kevin J. Adams, Professor, Ph.D., Department of History Master’s Advisor Kenneth J. Bindas, Professor, Ph.D, Chair, Department of History James L Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I. Republican Roots………………………………………………………19 II. A Vulnerable State……………………………………………………..35 III. Riots and Strikes………………………………………………………..64 IV. From Mobilization to Disillusionment………………………………….97 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….125 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..136 Introduction The Ohio Militia and National Guard before 1903 The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a profound change in the militia in the United States. Driven by the rivalry between modern warfare and militia tradition, the role as well as the ideology of the militia institution fitfully progressed beyond its seventeenth century origins. Ohio’s militia, the third largest in the country at the time, strove to modernize while preserving its relevance. Like many states in the early republic, Ohio’s militia started out as a sporadic group of reluctant citizens with little military competency. The War of the Rebellion exposed the serious flaws in the militia system, but also demonstrated why armed citizen-soldiers were necessary to the defense of the state. After the war ended, the militia struggled, but developed into a capable military organization through state-imposed reform. -

A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong

Tulsa Law Review Volume 48 Issue 2 Winter 2012 A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong Wyatt M. Cox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Wyatt M. Cox, A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong, 48 Tulsa L. Rev. 373 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol48/iss2/20 This Casenote/Comment is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cox: A Reserved Right Does Not Make a Wrong A RESERVED RIGHT DOES NOT MAKE A WRONG 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 374 II. TREATIES WITH THE TRIBAL NATIONS ............................................. 375 A. The Canons of Construction. ........................... ...... 375 B. The Power and Purpose of the Indian Treaty ............................... 376 C. The Equal Footing Doctrine .............................................377 D. A Brief Overview of the Policy History of Treaties ............ ........... 378 E. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.........................380 III. THE ESTABLISHMENT AND EXPANSION OF THE INDIAN RESERVED WATER RIGHT ....381 A. Winters v. United States: The Establishment of Reserved Indian Water Rights...................................................382 B. Arizona v. California:Not Only Enough Water to Fulfill the Purposes of Today, but Enough to Fulfill the Purposes of Forever ...................... 383 C. Cappaertv. United States: The Supreme Court Further Expands the Winters Doctrine ........................................ 384 IV. Two OKLAHOMA CASES THAT SUPPORT THE TRIBAL NATION CLAIMS .................... 385 A. Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma (The Arkansas River Bank Case) .................. -

Choctaw and Creek Removals

Chapter 6 Choctaw and Creek Removals The idea of indian removal as a government obligation first reared its head in 1802 when officials of the state of Georgia made an agreement with federal government officials. In the Georgia Compact, the state of Georgia gave up its claims to territorial lands west of that state in exchange for $1,250,000 and a promise that the federal government would abolish Indian title to Georgia lands as soon as possible. How seriously the government took its obligation to Georgia at the time of the agreement is unknown. The following year, however, the Louisiana Purchase was made, and almost immedi- ately, the trans-Mississippi area was seen by some as the answer to “The Indian Problem.” Not everyone agreed. Some congress- men argued that removal to the West was impractical because of land-hungry whites who could not be restrained from crossing the mighty river to obtain land. Although their conclusion was correct, it was probably made more in opposition to President Jefferson than from any real con- cern about the Indians or about practicality. Although some offers were made by government officials to officials of various tribes, little Pushmataha, Choctaw was done about removing the southeastern tribes before the War of 1812. warrior During that war several Indian tribes supported the British. After the war ended, many whites demanded that tribal lands be confiscated by Removals 67 the government as punishment for Indians’ treasonous activities. Many Americans included all tribes in their confiscationdemands , evidently feeling that all Indians were guilty, despite the fact that many tribes did not participate in the war. -

Kevin E. Dudley, Et Al.; Town of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma

INTERIOR BOARD OF INDIAN APPEALS Alan Chapman; Kevin E. Dudley, et al.; Town of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma; Muskogee County, Oklahoma; Oklahoma Tax Commission; Harold Wade; Quik Trip, Inc., et al.; City of Catoosa, Oklahoma v. Muskogee Area Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs 32 IBIA 101 (03/13/1998) Related Board case: 35 IBIA 285 United States Department of the Interior OFFICE OF HEARINGS AND APPEALS INTERIOR BOARD OF INDIAN APPEALS 4015 WILSON BOULEVARD ARLINGTON, VA 22203 ALAN CHAPMAN, : Order Lifting Stay, Vacating Appellant : Decisions, and Remanding KEVIN E. DUDLEY, et al., : Cases Appellants : TOWN OF FORT GIBSON, OKLAHOMA, : Appellant : MUSKOGEE COUNTY, OKLAHOMA, : COMMISSIONERS, : Appellants : ALAN CHAPMAN, : Appellant : KEVIN E. DUDLEY, et al., : Docket No. IBIA 96-115-A Appellants : Docket No. IBIA 96-119-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 96-122-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 96-123-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 96-124-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 96-125-A HAROLD WADE, : Docket No. IBIA 97-2-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 97-3-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 97-10-A Appellant : Docket No. IBIA 97-11-A QUIK TRIP, INC., et al., : Docket No. IBIA 97-12-A Appellants : Docket No. IBIA 97-14-A OKLAHOMA TAX COMMISSION, : Docket No. IBIA 97-40-A Appellant : CITY OF CATOOSA, OKLAHOMA : Appellant : : v. : : MUSKOGEE AREA DIRECTOR, : BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, : Appellee : March 13, 1998 32 IBIA 101 These are consolidated appeals from four decisions of the Muskogee Area Director, Bureau of Indian Affairs, to take certain tracts of land into trust. -

End: Grant Sidebar>>>>>

FINAL History of Wildwood 1860-1919 (chapter for 2018 printing) In the prior chapter, some of the key factors leading to the Civil War were discussed. Among them were the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the McIntosh Incident in 1836, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 which led to “the Bleeding Kansas” border war, and the Dred Scott case which was finally decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1856. Two books were published during this turbulent pre-war period that reflected the conflicts that were brewing. One was a work of fiction: Uncle Tom’s Cabin or a Life Among the Lowly by Harriet Beecher Stowe published in 1852. It was an anti-slavery novel and helped fuel the abolitionist movement in the 1850s. It was widely popular with 300,000 books sold in the United States in its first year. The second book was nonfiction: Twelve Years a Slave was the memoir of Solomon Northup. Northup was a free born black man from New York state who was kidnapped in Washington, D.C. and sold into slavery. He was in bondage for 12 years until family in New York secretly received information about his location and situation and arranged for his release with the assistance of officials of the State of New York. His memoir details the slave markets, the details of sugar and cotton production and the treatment of slaves on major plantations. This memoir, published in 1853, gave factual support to the story told in Stowe’s novel. These two books reflected and enhanced the ideological conflicts that le d to the Civil War. -

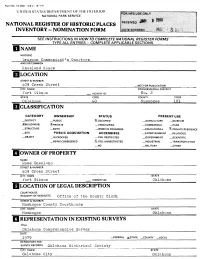

HCLASSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES •m^i:':^Mi:iMmm:mm-mmm^mmmmm:M;i:!m::::i!:- INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM 1 SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ [NAME HISTORIC Dragoon Commandant's Quarters_____________________________________ AND/OR COMMON Kneeland House________________________________________ LOCATION STREET & NUMBER /f09 Creek Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Fort Gibs on _. VICINITY OF No. 2. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Oklahoma uo Muskogee 101 HCLASSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM JSBUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ?_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT __|N PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Ross Kneeland STREETS. NUMBER Creek Street CITY. TOWN STATE Fort Gibson VICINITY OF Oklahoma LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDs.ETC. Office of the County Clerk STREET & NUMBER Muskogee County Courthouse CITY, TOWN STATE Muskogee Oklahoma REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Oklahoma Comprehensive Survey DATE 1979 —FEDERAL X-STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Oklahoma Historical Society CITY. TOWN STATE Oklahoma City Oklahoma DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE XGOOD —RUINS .^ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Paint and a modern composition roof tend to disguise the age of the Dragoon Commandant's Quarters. -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ...................................................................................................... -

By Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklah

FEDERAL REFUGEES FROM INDIAN TERRITORY, 1861-1867 By JERRY LEON GILL /( Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1967 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo~ the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1973 :;-1' ., '' J~~ /'77~' G415 f. •. &if'• .~:,; . ;.. , : - i \ . ..J ') .: • .·•.,. -~ 1•, j ( . i • • I OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OCT 8 1973 FEDERAL REFUGEES FROM IND IAN TERRITORY, 1861-1867 Thesis Approvedr cPean "of the Graduate College ii PREFACE This study is concerned with the influence of the Civil War on the Indian tribes residing in Indian Territory who chose to remain loyal to the United States government during the conflict. Emphasis is placed on the Cherokee, Cree~, Chickasaw, and Seminole Indians, but all tribes and portions of Indian Territory tribes loyal to the United States during the Civil War are included in the study. Confederate military control of Indian Territory early in the Civil War forced the Indians loyal to the United States to flee north from Indian Territory. Before the war had ended,·approximately 10,500 Feder al refugee Indians had scattered across Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, and :Mexico. The reasons why these Indians remained loyal to the United States, their exodus from Indian Territory, their exile, and their return to Indian Territory are documented and evaluated in this study. The suffering and death expe:i;ienced by these refugees are unique in Civil War history, and far surpassed the de.privation and sacrifices made by other civilian populations. Hundreds of non-combatants,. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

Oklahoma Women

Oklahomafootloose andWomen: fancy–free Newspapers for this educational program provided by: 1 Oklahoma Women: Footloose and Fancy-Free is an educational supplement produced by the Women’s Archives at Oklahoma State University, the Oklahoma Commission on the Status of Women and The Oklahoman. R. Darcy Jennifer Paustenbaugh Kate Blalack With assistance from: Table of Contents Regina Goodwin Kelly Morris Oklahoma Women: Footloose and Fancy-Free 2 Jordan Ross Women in Politics 4 T. J. Smith Women in Sports 6 And special thanks to: Women Leading the Fight for Civil and Women’s Rights 8 Trixy Barnes Women in the Arts 10 Jamie Fullerton Women Promoting Civic and Educational Causes 12 Amy Mitchell Women Take to the Skies 14 John Gullo Jean Warner National Women’s History Project Oklahoma Heritage Association Oklahoma Historical Society Artist Kate Blalack created the original Oklahoma Women: watercolor used for the cover. Oklahoma, Foot-Loose and Fancy Free is the title of Footloose and Fancy-Free Oklahoma historian Angie Debo’s 1949 book about the Sooner State. It was one of the Oklahoma women are exciting, their accomplishments inspirations for this 2008 fascinating. They do not easily fi t into molds crafted by Women’s History Month supplement. For more on others, elsewhere. Oklahoma women make their own Angie Debo, see page 8. way. Some stay at home quietly contributing to their families and communities. Some exceed every expectation Content for this and become fi rsts in politics and government, excel as supplement was athletes, entertainers and artists. Others go on to fl ourish developed from: in New York, California, Japan, Europe, wherever their The Oklahoma Women’s fancy takes them.