William Clifton Mabry Aug

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choctaw Code Talkers

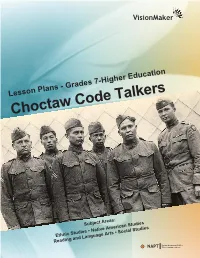

VisionMaker Lesson Plans - Grades 7-Higher Education Choctaw Code Talkers Subject Areas: Ethnic Studies • Native American Studies Reading and Language Arts • Social Studies NAPT Native American Public Telecommunications VisionMaker Procedural Notes for Educators Film Synopsis In 1918, not yet citizens of the United States, Choctaw men of the American Expeditionary Forces were asked to use their Native language as a powerful tool against the German Forces in World War I, setting a precedent for code talking as an effective military weapon and establishing them as America's original Code Talkers. A Note to Educators These lesson plans are created for students in grades 7 through higher education. Each lesson can be adapted to meet your needs. Robert S. Frazier, grandfather of Code Talker Tobias Frazier, and sheriff of Jack's Fork and Cedar Counties Image courtesy of "Choctaw Code Talkers" Native American Public 2 NAPT Telecommunications VisionMaker Objectives and Curriculum Standards a. Use context (e.g., the overall meaning of a sentence, Objectives paragraph, or text; a word’s position or function in a sentence) These activities are designed to give participants as a clue to the meaning of a word or phrase. learning experiences that will help them understand and b. Identify and correctly use patterns of word changes that indicate different meanings or parts of speech. consider the history of the sovereign Choctaw Nation c. Consult general and specialized reference materials (e.g., of Oklahoma, and its unique relationship to the United dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses), both print and digital, to States of America; specifically how that relates to the find the pronunciation of words, a word or determine or clarify documentary, Choctaw Code Talkers. -

A Critical Analysis of the Black President in Film and Television

“WELL, IT IS BECAUSE HE’S BLACK”: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BLACK PRESIDENT IN FILM AND TELEVISION Phillip Lamarr Cunningham A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2011 Committee: Dr. Angela M. Nelson, Advisor Dr. Ashutosh Sohoni Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Butterworth Dr. Susana Peña Dr. Maisha Wester © 2011 Phillip Lamarr Cunningham All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Ph.D., Advisor With the election of the United States’ first black president Barack Obama, scholars have begun to examine the myriad of ways Obama has been represented in popular culture. However, before Obama’s election, a black American president had already appeared in popular culture, especially in comedic and sci-fi/disaster films and television series. Thus far, scholars have tread lightly on fictional black presidents in popular culture; however, those who have tend to suggest that these presidents—and the apparent unimportance of their race in these films—are evidence of the post-racial nature of these texts. However, this dissertation argues the contrary. This study’s contention is that, though the black president appears in films and televisions series in which his presidency is presented as evidence of a post-racial America, he actually fails to transcend race. Instead, these black cinematic presidents reaffirm race’s primacy in American culture through consistent portrayals and continued involvement in comedies and disasters. In order to support these assertions, this study first constructs a critical history of the fears of a black presidency, tracing those fears from this nation’s formative years to the present. -

Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina David W

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 8-9-2014 Hard Rows to Hoe: Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina David W. Dangerfield University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dangerfield, D. W.(2014). Hard Rows to Hoe: Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2772 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARD ROWS TO HOE: FREE BLACK FARMERS IN ANTEBELLUM SOUTH CAROLINA by David W. Dangerfield Bachelor of Arts Erskine College, 2005 Master of Arts College of Charleston, 2009 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Mark M. Smith, Major Professor Lacy K. Ford, Committee Member Daniel C. Littlefield, Committee Member David T. Gleeson, Committee Member Lacy K. Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by David W. Dangerfield, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation and my graduate education have been both a labor and a vigil – and neither was undertaken alone. I am grateful to so many who have worked and kept watch beside me and would like to offer a few words of my sincerest appreciation to the teachers, colleagues, friends, and family who have helped me along the way. -

1918 Journal

; 1 SUPEEME COUET OE THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 7, 1918. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day, Mr. Justice Van Devanter, Mr. Justice Pitney, Mr. Justice McReynolds, Mr. Justice Brandeis, and Mr. Justice Clarke. John Carlos Shields, of Detroit, Mich.; Willis G. Clarke, of Detroit, Mich.; J. Merrill Wright, of Pittsburgh, Pa.; David L. Starr, of Pittsburgh, Pa.; Albert G. Liddell, of Pittsburgh, Pa.; Claude R. Porter, of Centerville, Iowa; Henry F. May, of Denver, Colo. ; James H. Anderson, of Chattanooga, Tenn. ; Robert A. Hun- ter, of Shreveport, La.; J. W. Pless, of Marion, N. C. ; Stanley Moore, of Oakland, Cal. ; John Evarts Tracy, of Milwaukee, Wis.; Walter Carroll Low, of New York City; Norbert Heinsheimer, of New York City ; John R. Lazenby, of Boston, Mass. ; Frederick W. Gaines, of Toledo, Ohio; Roger Hinds, of New York City; Henry Wiley Johnson, of Savannah, Ga. ; Frederick R. Shearer, of Wash- ington, D. C. ; Walter C. Balderson, of Washington, D. C. ; Thomas M. Kirby, of Cleveland, Ohio; Arthur Mayer, of New York City; Samuel Marcus, of New York City; Kheve Henry Rosenberg, of New York City ; Isidor Kalisch, of Newark, N. J. ; Francis Lafferty, of Newark, N. J.; C. H. Henkel, of Mansfield, Ohio; Frederick A. Mohr, of Auburn, N. Y. Henry A. Brann, jr., of New York City; ; Frank Wagaman, of Hagerstown, Md. Spotswood D. Bowers, of G. ; New York City; Morris L. Johnston, of Chicago, 111.; Benjamin W. Dart, of New Orleans, La.; Maryus Jones, of Newport News, Va. -

The University of Tulsa Magazine Is Published Three Times a Year Major National Scholarships

the university of TULSmagazinea 2001 spring NIT Champions! TU’s future is in the bag. Rediscover the joys of pudding cups, juice boxes, and sandwiches . and help TU in the process. In these times of tight budgets, it can be a challenge to find ways to support worthy causes. But here’s an idea: Why not brown bag it,and pass some of the savings on to TU? I Eating out can be an unexpected drain on your finances. By packing your lunch, you can save easy dollars, save commuting time and trouble, and maybe even eat healthier, too. (And, if you still have that childhood lunch pail, you can be amazingly cool again.) I Plus, when you share your savings with TU, you make a tremendous difference.Gifts to our Annual Fund support a wide variety of needs, from purchase of new equipment to maintenance of facilities. All of these are vital to our mission. I So please consider “brown bagging it for TU.” It could be the yummiest way everto support the University. I Watch the mail for more information. For more information on the TU Annual Fund, call (918) 631-2561, or mail your contribution to The University of Tulsa Annual Fund, 600 South College Avenue, Tulsa, OK 74104-3189. Or visit our secure donor page on the TU website: www.utulsa.edu/development/giving/. the university of TULSmagazinea features departments 16 A Poet’s Perspective 2 Editor’s Note 2001 By Deanna J. Harris 3 Campus Updates spring American poet and philosopher Robert Bly is one of the giants of 20th century literature. -

This Fact Sheet Is Prepared by the Sons of Confederate

AMERICAN INDIAN CONFEDERATES *** After The War Between the States began, President Jefferson Davis addressed the Congress of the Confederate States of America to establish a Bureau of Indian Affairs.1 While the North was apathetic concerning the plight of American Indians2, the South determinedly created a positive relationship with “Indian Country.”3 In May 1861 Confederate envoy Albert Pike arrived in Indian Territory so that he could negotiate treaty terms with American Indians who were originally from the South.4 Pike found that most Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks and Seminoles immediately allied themselves with the Confederacy,5 but Cherokees were conflicted and bitterly divided just as other Americans. Still others in Indian Territory wanted neutrality.6 After their careful consideration, most American Indians living in Indian Territory or a confederated state believed that siding with the Confederacy was in their best interest.7 Confederate treaties were quite extensive, explicit, and inclusive which American Indians viewed favorably; one such treaty presented national sovereignty, confederate citizenship possibilities, and an entitled delegate in the Confederate House of Representatives.8 However, the situation was far from ideal despite treaty promises.9 American Indian Confederate soliders, who were expecting arms; supplies; and pay, got little or none.10 Confederate units often commandeered supplies that were designated for Indian Territory confederates.11 Such events caused friction between high ranking Confederate military -

Grade 8 Social Studies TEKS Curriculum Framework

____________________________________________________________________________________ TEKS Curriculum Framework for STAAR Alternate 2 Grade 8 Social Studies Copyright © September 2016, Texas Education Agency. All rights reserved. Reproduction of all or portions of this work is prohibited without express written permission from the Texas Education Agency. Social Studies TEKS Curriculum Framework for STAAR Alternate 2 | Grade 8 STAAR Reporting Category 1 – History: The student will demonstrate an understanding of issues and events in U.S. history. TEKS Knowledge and Skills Statement/ Essence of TEKS Knowledge and Skills Statement/ STAAR-Tested Student Expectations STAAR-Tested Student Expectations (8.1) History. The student understands traditional historical points of Recognizes important dates and time periods in U.S. history reference in U.S. history through 1877. The student is expected to through 1877. (A) identify the major eras and events in U.S. history through 1877, including colonization, revolution, drafting of the Declaration of Independence, creation and ratification of the Constitution, religious revivals such as the Second Great Awakening, early republic, the Age of Jackson, westward expansion, reform movements, sectionalism, Civil War, and Reconstruction, and describe their causes and effects; Readiness Standard (B) apply absolute and relative chronology through the sequencing of significant individuals, events, and time periods; Supporting Standard (C) explain the significance of the following dates: 1607, founding of Jamestown; -

Incorporating Emancipation Celebrations in the Sixth Grade

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 427 992 SO 029 441 AUTHOR Peterson, Lorna TITLE Incorporating Emancipation Celebrations in the Sixth Grade Social Studies and Library Skills Curriculum: A University, School, and Public Library Program on Juneteenth. PUB DATE 1997-03-00 NOTE 15p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (Chicago, IL, March 24-28, 1997). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College School Cooperation; Grade 6; Higher Education; *Information Technology; Intermediate Grades; *Library Skills; Middle Schools; Primary Sources; Public Education; *Research Skills; Skill Development; Social Studies; Student Development; *United States History IDENTIFIERS Douglass (Frederick); Historical Research; Juneteenth; State University of New York Buffalo; Texas ABSTRACT This paper describes a cooperative effort, part of a school/university partnership between the Graduate School of Education and the School of Information and Library Studies at the State University of New York at Buffalo, in which a core curriculum was developed and coordinated in library research skills and information technology for two sixth-grade classes in an urban public school. The paper explains that using the Texas emancipation celebration, Juneteenth, as the intellectual domain, students learned how and when to use various libraries and library resources, and how historians answer questions through primary document research. Special instruction on the use of the school library media center, the neighborhood branch public library, the main library of Buffalo and Erie County Public Library (a research library), and the State University at Buffalo Undergraduate Library provided students with the opportunity to research, read, and participate in knowledge production. -

Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Kentucky Library - Serials Society Newsletter

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Kentucky Library - Serials Society Newsletter Summer 1992 Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter Volume 15, Number 2 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/longhunter_sokygsn Part of the Genealogy Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter Volume 15, Number 2" (1992). Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter. Paper 123. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/longhunter_sokygsn/123 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JIi!~ HUNT[R 6ovihorn ~entvck~ <5~n~nlo9iCo.l GOCi~19 + VOLUME XV, NUMBER 2 SOUTHERN KENTUCKY GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY P. -O. Box 1t111Mt 1782- Bowling Green, KY 42102-lei/73L 1992 OFFICERS AND CHAIRPERSONS ***************************************************************************** , President: Mrs. Betty Boyd Lyne, 613 E. 11th St., Bowling Green, KY 42101, Ph. 502 843 9452 Vice President: Mrs. Mildred E. Collier, 1644 Smallhouse Rd., Bowling Green, KY 42104, Ph. 502 843 4753 Recording Secretary: Mrs. Mary Garrett, 5409 Bowling Green Rd., Franklin, KY, 42134, Ph. 1 502 586 4086 Corresponding Secretary Mrs. Sue Sensenig, 9706 Porter Pike Rd., Oakland, KY 42159, Ph. 563 9853 Treasurer Gene A. Whicker, 1118 Nahm Drive , Bowling Green, KY, 42104, Ph. 502 842 5382 Sargent at Arms/Parliam. Leroy Collier, 1644 Smallhouse Rd., Bowling Green, KY, 42104, Ph. -

The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-01-08 Southern Pride and Yankee Presence: The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865 Ruminski, Jarret Ruminski, J. (2013). Southern Pride and Yankee Presence: The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865 (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27836 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/398 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Southern Pride and Yankee Presence: The Limits of Confederate Loyalty in Civil War Mississippi, 1860-1865 by Jarret Ruminski A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER, 2012 © Jarret Ruminski 2012 Abstract This study uses Mississippi from 1860 to 1865 as a case-study of Confederate nationalism. It employs interdisciplinary literature on the concept of loyalty to explore how multiple allegiances influenced people during the Civil War. Historians have generally viewed Confederate nationalism as weak or strong, with white southerners either united or divided in their desire for Confederate independence. This study breaks this impasse by viewing Mississippians through the lens of different, co-existing loyalties that in specific circumstances indicated neither popular support for nor rejection of the Confederacy. -

From an Empty Room at Princeton

GERALD L C OOPER From An Empty On Room At Princeton Scholarshıp On Scholarship From An Empty Room at Princeton GERALD L COOPER Copyright 2010 Gerald L. Cooper. All rights reserved. Editorial: Alfred P. Scott Graphic Design: Jack Amos Printed in the United States of America This book is available in PDF format at www.talkeetna.com This is dedicated to the one I love: Prior Meade Cooper I never thought I’d marry a May Queen. Contents Foreword i My Early Years 1 Getting an Education, Not the Confederacy 26 A Log Cabin on the Corrotoman 36 Seeing Life in a New Light 46 The Neck, the River and College Prep 64 An Empty Room at Princeton 80 Life and Work in Boarding Schools 105 A New Era at Woodberry Forest 132 Ed Dorsey: Powerful and Effective 162 To the Children of Tomorrow 171 To Winston-Salem and Beyond 195 A Different Kind of University 204 WSSU—Where Failure Was Not An Option 228 College Access at Career End 242 Changing Lives in Rural Virginia 273 Leading to Diversity at the University of Virginia 286 Epilogue 301 End Notes 305 ON SC HOLAR S HIP Foreword Pursuits of my own choice … I would be indulged … with the blessings of domestic society, and pursuits of my own choice … Thomas Jefferson to his daughter, Martha, 1807 s I approached age sixty-five in the year 2000, several of Amy male contemporaries told me how they were resisting retirement to the last possible moment. Unlike them, I was ready to retire. I knew that retirement would give me the opportunity to concentrate on two activities I had wanted to pursue more deeply for most of my life: broad-based reading and reflective writing. -

Dear Charlie Richie

SOUTHEASTERN AMERICAN INDIANS DURING THE CIVIL WAR *** American Indians participated in America’s deadliest conflict. While a large number of Indians enlisted with the North, the South, by far, had the largest enrollment. After he joined his respective command, the American Indian soldier was found fighting in the Eastern, Western, or Trans-Mississippi Theaters. After the War ended, the greater amount of historical focus was given to Trans- Mississippi Indians while those tribes found east were neglected of any significant historical attention. Authors, such as Annie H. Abel, wrote volumes concerning the struggle in the Trans-Mississippi West. However, American Indians, who were found east of the Mississippi River, have a fragmented and obscured Civil War history. Since Southeastern Indian Confederates have been condemned to historical footnotes, it is time to take a closer look and ask some basic, but overlooked, questions. Why were these Indians in the South after removal? Why did they join the Confederacy? Who were these Southeastern Indian Confederates? Who were their white patrons? What did they accomplish? These are simple questions but profoundly revealing. Although the majority of Southeastern Indians were sent west during the removal years, small groups elected to remain in their old homelands. Florida’s Seminoles resisted removal through decades of war and earned the right to stay in the Everglades. Mississippi’s Choctaws were allowed to stay because of an article provision found in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. North Carolina’s Cherokees remained largely due to the efforts of a white man by the name of William H. Thomas.