(Miller) Status: High Concern. Saratoga Springs Pupfish Numbers Ap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California's Freshwater Fishes: Status and Management

California’s freshwater fishes: status and management Rebecca M. Quiñones* and Peter B. Moyle Center for Watershed Sciences, University of California at Davis, One Shields Ave, Davis, 95616, USA * correspondence to [email protected] SUMMARY Fishes in Mediterranean climates are adapted to thrive in streams with dy- namic environmental conditions such as strong seasonality in flows. Howev- er, anthropogenic threats to species viability, in combination with climate change, can alter habitats beyond native species’ environmental tolerances and may result in extirpation. Although the effects of a Mediterranean cli- mate on aquatic habitats in California have resulted in a diverse fish fauna, freshwater fishes are significantly threatened by alien species invasions, the presence of dams, and water withdrawals associated with agricultural and urban use. A long history of habitat degradation and dependence of salmonid taxa on hatchery supplementation are also contributing to the decline of fish- es in the state. These threats are exacerbated by climate change, which is also reducing suitable habitats through increases in temperatures and chang- es to flow regimes. Approximately 80% of freshwater fishes are now facing extinction in the next 100 years, unless current trends are reversed by active conservation. Here, we review threats to California freshwater fishes and update a five-tiered approach to preserve aquatic biodiversity in California, with emphasis on fish species diversity. Central to the approach are man- agement actions that address conservation at different scales, from single taxon and species assemblages to Aquatic Diversity Management Areas, wa- tersheds, and bioregions. Keywords: alien fishes, climate change, conservation strategy, dams Citation: Quiñones RM, Moyle PB (2015) California’s freshwater fishes: status and man- agement. -

§4-71-6.5 LIST of CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November

§4-71-6.5 LIST OF CONDITIONALLY APPROVED ANIMALS November 28, 2006 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Plesiopora FAMILY Tubificidae Tubifex (all species in genus) worm, tubifex PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Crustacea ORDER Anostraca FAMILY Artemiidae Artemia (all species in genus) shrimp, brine ORDER Cladocera FAMILY Daphnidae Daphnia (all species in genus) flea, water ORDER Decapoda FAMILY Atelecyclidae Erimacrus isenbeckii crab, horsehair FAMILY Cancridae Cancer antennarius crab, California rock Cancer anthonyi crab, yellowstone Cancer borealis crab, Jonah Cancer magister crab, dungeness Cancer productus crab, rock (red) FAMILY Geryonidae Geryon affinis crab, golden FAMILY Lithodidae Paralithodes camtschatica crab, Alaskan king FAMILY Majidae Chionocetes bairdi crab, snow Chionocetes opilio crab, snow 1 CONDITIONAL ANIMAL LIST §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Chionocetes tanneri crab, snow FAMILY Nephropidae Homarus (all species in genus) lobster, true FAMILY Palaemonidae Macrobrachium lar shrimp, freshwater Macrobrachium rosenbergi prawn, giant long-legged FAMILY Palinuridae Jasus (all species in genus) crayfish, saltwater; lobster Panulirus argus lobster, Atlantic spiny Panulirus longipes femoristriga crayfish, saltwater Panulirus pencillatus lobster, spiny FAMILY Portunidae Callinectes sapidus crab, blue Scylla serrata crab, Samoan; serrate, swimming FAMILY Raninidae Ranina ranina crab, spanner; red frog, Hawaiian CLASS Insecta ORDER Coleoptera FAMILY Tenebrionidae Tenebrio molitor mealworm, -

Solar Energy, National Parks, and Landscape Protection in the Desert

Solar Energy, National Parks, and Landscape Protection in the Desert Southwest - 1 - Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ - 3 - Part I. Solar energy tsunami headed for the American Southwest ......................................... - 6 - Solar Energy: From the fringes and into the light .................................................................. - 6 - The Southwest: Regional Geography and Environmental Features ..................................... - 12 - Regional Stakeholders and Shared Resources ...................................................................... - 23 - Part II. Case Studies of Approved Solar Energy Facilities .................................................... - 27 - Amargosa Farm Road Solar Energy Plant Near Death Valley National Park: Preserving Water Resources to Protect Critically Endangered Species............................................................. - 27 - Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System Near Mojave National Preserve: Protecting Endangered Desert Tortoises and Scenic Resources ............................................................ - 42 - Desert Sunlight Solar Farm Project Near Joshua Tree NP: Protecting Park Scenery from Adjacent Development .......................................................................................................... - 56 - Part III. The Department of Interior’s Programmatic Solar Energy Environmental Impact Statement ............................................................................................................................. -

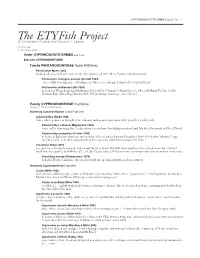

The Etyfish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J

CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3) · 1 The ETYFish Project © Christopher Scharpf and Kenneth J. Lazara COMMENTS: v. 3.0 - 13 Nov. 2020 Order CYPRINODONTIFORMES (part 3 of 4) Suborder CYPRINODONTOIDEI Family PANTANODONTIDAE Spine Killifishes Pantanodon Myers 1955 pan(tos), all; ano-, without; odon, tooth, referring to lack of teeth in P. podoxys (=stuhlmanni) Pantanodon madagascariensis (Arnoult 1963) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Madagascar, where it is endemic [extinct due to habitat loss] Pantanodon stuhlmanni (Ahl 1924) in honor of Franz Ludwig Stuhlmann (1863-1928), German Colonial Service, who, with Emin Pascha, led the German East Africa Expedition (1889-1892), during which type was collected Family CYPRINODONTIDAE Pupfishes 10 genera · 112 species/subspecies Subfamily Cubanichthyinae Island Pupfishes Cubanichthys Hubbs 1926 Cuba, where genus was thought to be endemic until generic placement of C. pengelleyi; ichthys, fish Cubanichthys cubensis (Eigenmann 1903) -ensis, suffix denoting place: Cuba, where it is endemic (including mainland and Isla de la Juventud, or Isle of Pines) Cubanichthys pengelleyi (Fowler 1939) in honor of Jamaican physician and medical officer Charles Edward Pengelley (1888-1966), who “obtained” type specimens and “sent interesting details of his experience with them as aquarium fishes” Yssolebias Huber 2012 yssos, javelin, referring to elongate and narrow dorsal and anal fins with sharp borders; lebias, Greek name for a kind of small fish, first applied to killifishes (“Les Lebias”) by Cuvier (1816) and now a -

Monitoring and Understanding Toxic Cyanobacteria and Cochlodinium Polykrikoides Blooms in Suffolk County

MONITORING AND UNDERSTANDING TOXIC CYANOBACTERIA AND COCHLODINIUM POLYKRIKOIDES BLOOMS IN SUFFOLK COUNTY A FINAL REPORT BY CHRISTOPHER J. GOBLER, STONY BROOK UNIVERSITY SUBMITTED SEPTEMBER 2013 REVISED MAY 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Executive Summary……………………………………………………………pages 3- 6 Task 1. – Literature and Regulatory Review…………………………………pages 7 - 14 Task 2. –Summer monitoring of freshwater bathing beach lakes in Suffolk County. Suffolk County Bathing Beaches………………………………….…………pages 15 - 16 Task 3. Seasonal monitoring the most toxic lakes in Suffolk County…..……pages 17 - 25 Task 4. Cyanotoxin findings and final report………………………...…………..pages 26 Task 5 & 6. Assess the ability of Cochlodinium polykrikoides to form cysts; Quantify the production and densities of Cochlodinium polykrikoides cysts before, during and after blooms………………………………………………………………..………pages 27 - 57 Task 7. Assess the temperature tolerance of Cochlodinium polykrikoides….pages 58 - 61 Task 8. Assess the mechanism of toxicity of Cochlodinium polykrikoides....pages 62 - 93 Task 9. Explore the vulnerability of Suffolk County fish populations to Cochlodinium polykrikoides………………………………………………………...………pages 94 - 113 Task 10. Prepare a final report regarding Cochlodinium polykrikoides results….pages 114 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This project, Monitoring and Understanding Toxic Cyanobacteria and Cochlodinium polykrikoides Blooms in Suffolk County, was funded by Suffolk County Capital Project 8224, Harmful Algal Blooms, and was initiated to address ongoing blooms of toxic cyanobacteria and Cochlodinium polykrikoides in Suffolk County waters. Cyanobacteria Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are microscopic organisms found in both marine and fresh water environments. Under favorable conditions of sunlight, temperature, and nutrient concentrations, cyanobacteria can form massive blooms that discolor the water and often result in a scums and floating mats on the water’s surface. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Relation of Desert Pupfish Abundance to Selected Environmental Variables

Environmental Biology of Fishes (2005) 73: 97–107 Ó Springer 2005 Relation of desert pupfish abundance to selected environmental variables in natural and manmade habitats in the Salton Sea basin Barbara A. Martin & Michael K. Saiki U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Western Fisheries Research Center-Dixon Duty Station, 6924 Tremont Road, Dixon, CA 95620, U.S.A. (e-mail: [email protected]) Received 6 April 2004 Accepted 12 October 2004 Key words: species assemblages, predation, water quality, habitat requirements, ecological interactions, endangered species Synopsis We assessed the relation between abundance of desert pupfish, Cyprinodon macularius, and selected biological and physicochemical variables in natural and manmade habitats within the Salton Sea Basin. Field sampling in a natural tributary, Salt Creek, and three agricultural drains captured eight species including pupfish (1.1% of the total catch), the only native species encountered. According to Bray– Curtis resemblance functions, fish species assemblages differed mostly between Salt Creek and the drains (i.e., the three drains had relatively similar species assemblages). Pupfish numbers and environmental variables varied among sites and sample periods. Canonical correlation showed that pupfish abundance was positively correlated with abundance of western mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis, and negatively correlated with abundance of porthole livebearers, Poeciliopsis gracilis, tilapias (Sarotherodon mossambica and Tilapia zillii), longjaw mudsuckers, Gillichthys mirabilis, and mollies (Poecilia latipinna and Poecilia mexicana). In addition, pupfish abundance was positively correlated with cover, pH, and salinity, and negatively correlated with sediment factor (a measure of sediment grain size) and dissolved oxygen. Pupfish abundance was generally highest in habitats where water quality extremes (especially high pH and salinity, and low dissolved oxygen) seemingly limited the occurrence of nonnative fishes. -

Cyprinodon Nevadensis Mionectes Ash Meadows Amargosa Pupfish

Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfsh Cyprinodon nevadensis mionectes WAP 2012 species due to impacts from introduced detrimental aquatc species, habitat degradaton, and federal endangered status. Agency Status NV Natural Heritage G2T2S2 USFWS LE BLM-NV Sensitve State Prot Threatened Fish NAC 503.065.3 CCVI Presumed Stable TREND: Trend is stable to increasing with contnued on-going restoraton actvites. DISTRIBUTION: Springs and associated springbrooks, outlow stream systems and terminal marshes within Ash Meadows Natonal Wildlife Refuge, Nye Co., NV. GENERAL HABITAT AND LIFE HISTORY: This species is isolated to warm springs and outlows in Ash Meadows NWR including Point of Rocks, Crystal Springs, and the Carson Slough drainage. Pupfshes feed generally on substrate; feeding territories are ofen defended by pupfshes. Diet consists of mainly algae and detritus however, aquatc insects, crustaceans, snails and eggs are also consumed. Spawning actvity is typically from February to September and in some cases year round. Males defend territories vigorously during breeding season (Soltz and Naiman 1978). In warm springs, fsh may reach sexual maturity in 4-6 weeks. Reproducton variable: in springs, pupfsh breed throughout the year, may have 8-10 generatons/year; in streams, breeds in spring and summer, 2-3 generatons/year (Moyle 1976). In springs, males establish territories over sites suitable for ovipositon. Short generaton tme allows small populatons to be viable. Young adults typically comprise most of the biomass of a populaton. Compared to other C. nevadensis subspecies, this pupfsh has a short deep body and long head with typically low fn ray and scale counts (Soltz and Naiman 1978). CONSERVATION CHALLENGES: Being previously threatened by agricultural use of the area (loss and degradaton of habitat resultng from water diversion and pumping) and by impending residental development, the TNC purchased property, which later became the Ash Meadows NWR. -

Three New Pupfish Species, Cyprinodon (Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae), from Chihuahua, México, and Arizona, USA Author(S): W

Three New Pupfish Species, Cyprinodon (Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae), from Chihuahua, México, and Arizona, USA Author(s): W. L. Minckley, Robert Rush Miller and Steven Mark Norris Source: Copeia, Vol. 2002, No. 3 (Aug. 15, 2002), pp. 687-705 Published by: American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1448150 . Accessed: 23/07/2014 15:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Copeia. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.123.44.23 on Wed, 23 Jul 2014 15:57:21 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Copeia,2002(3), pp. 687-705 Three New Pupfish Species, Cyprinodon(Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae), from Chihuahua, Mexico, and Arizona, USA W. L. MINCKLEY,ROBERT RUSH MILLER,AND STEVENMARK NORRIS Three new species of Cyprinodon(Teleostei, Cyprinodontidae)are described,each long recognized as distinct. Cyprinodonpisteri occupies a varietyof systems and hab- itats in the Lago de Guzmin complex basin in northern Chihuahua,Mexico. It is distinguishedby its dusky to black dorsal fin and narrowor inconspicuousterminal bar on the caudal fin in mature males. -

Recovery Plan for the Amargosa Vole

Recovery Plan for the Amargosa Vole (Microtus californicus scirpensis) ( As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the ~ Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use ofour land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environ mental and cultural values of our national parks ~, and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energyand mineral resourcesand works toassure that ~‘ theirdevelopment is in the best interests ofall our people. ~4 The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people ~<‘ who live in island Territories under U.S. administration. AMARGOSA VOLE (Microtus cahfornicus scirpensis) RECOVERY PLAN September, 1997 7— U.S. Department ofthe Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Region One, Portland, Oregon DISCLAIMER PAGE Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes prepared with the assistance ofrecovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. -

Distribution of Amargosa River Pupfish (Cyprinodon Nevadensis Amargosae) in Death Valley National Park, CA

California Fish and Game 103(3): 91-95; 2017 Distribution of Amargosa River pupfish (Cyprinodon nevadensis amargosae) in Death Valley National Park, CA KRISTEN G. HUMPHREY, JAMIE B. LEAVITT, WESLEY J. GOLDSMITH, BRIAN R. KESNER, AND PAUL C. MARSH* Native Fish Lab at Marsh & Associates, LLC, 5016 South Ash Avenue, Suite 108, Tempe, AZ 85282, USA (KGH, JBL, WJG, BRK, PCM). *correspondent: [email protected] Key words: Amargosa River pupfish, Death Valley National Park, distribution, endangered species, monitoring, intermittent streams, range ________________________________________________________________________ Amargosa River pupfish (Cyprinodon nevadensis amargosae), is one of six rec- ognized subspecies of Amargosa pupfish (Miller 1948) and survives in waters embedded in a uniquely harsh environment, the arid and hot Mojave Desert (Jaeger 1957). All are endemic to the Amargosa River basin of southern California and Nevada (Moyle 2002). Differing from other spring-dwelling subspecies of Amargosa pupfish (Cyprinodon ne- vadensis), Amargosa River pupfish is riverine and the most widely distributed, the extent of which has been underrepresented prior to this study (Moyle et al. 2015). Originating on Pahute Mesa, Nye County, Nevada, the Amargosa River flows intermittently, often under- ground, south past the towns of Beatty, Shoshone, and Tecopa and through the Amargosa River Canyon before turning north into Death Valley National Park and terminating at Badwater Basin (Figure 1). Amargosa River pupfish is data deficient with a distribution range that is largely unknown. The species has been documented in Tecopa Bore near Tecopa, Inyo County, CA (Naiman 1976) and in the Amargosa River Canyon, Inyo and San Bernardino Counties, CA (Williams-Deacon et al. -

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(S): Noel M

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(s): Noel M. Burkhead Source: BioScience, 62(9):798-808. 2012. Published By: American Institute of Biological Sciences URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1525/bio.2012.62.9.5 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Articles Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 NOEL M. BURKHEAD Widespread evidence shows that the modern rates of extinction in many plants and animals exceed background rates in the fossil record. In the present article, I investigate this issue with regard to North American freshwater fishes. From 1898 to 2006, 57 taxa became extinct, and three distinct populations were extirpated from the continent. Since 1989, the numbers of extinct North American fishes have increased by 25%. From the end of the nineteenth century to the present, modern extinctions varied by decade but significantly increased after 1950 (post-1950s mean = 7.5 extinct taxa per decade).