Thameslink Programme Baseline Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oyster Conditions of Use on National Rail Services

Conditions of Use on National Rail services 1 October 2015 until further notice 1. Introduction 1.1. These conditions of use (“Conditions of Use”) set out your rights and obligations when using an Oyster card to travel on National Rail services. They apply in addition to the conditions set out in the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, which you can view and download from the National Rail website nationalrail.co.uk/nrcoc. Where these Conditions of Use differ from the National Rail Conditions of Carriage, these Conditions of Use take precedence when you are using your Oyster card. 1.2 When travelling on National Rail services, you will also have to comply with the Railway Byelaws. You can a get free copy of these at most staffed National Rail stations, or download a copy from the Department for Transport website dft.gov.uk. 1.3 All Train Companies operating services into the London Fare Zones Area accept valid Travelcards issued on Oyster cards, except Heathrow Express and Southeastern High Speed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International. In addition, the following Train Companies accept pay as you go on Oyster cards for travel on their services within the London National Rail Pay As You Go Area. Abellio Greater Anglia Limited (trading as Greater Anglia) The Chiltern Railway Company Limited (trading as Chiltern Railways) First Greater Western Limited (trading as Great Western Railway) (including Heathrow Connect services between London Paddington and Hayes & Harlington) GoVia Thameslink Railway Limited (trading as Great Northern, as Southern and as Thameslink) London & Birmingham Railway Limited (trading as London Midland) London & South Eastern Railway Company (trading as Southeastern) (Special fares apply on Southeaster highspeed services between London St Pancras International and Stratford International). -

Discover London

Discover London Page 1 London Welcome to your free “Discover London” city guide. We have put together a quick and easy guide to some of the best sites in London, a guide to going out and shopping as well as transport information. Don’t miss our local guide to London on page 31. Enjoy your visit to London. Visitor information...........................................................................................................Page 3 Tate Modern....................................................................................................................Page 9 London Eye.....................................................................................................................Page 11 The Houses of Parliament...............................................................................................Page 13 Westminster Abbey........................................................................................................Page 15 The Churchill War Rooms...............................................................................................Page 17 Tower of London............................................................................................................Page 19 Tower Bridge..................................................................................................................Page 21 Trafalgar Square.............................................................................................................Page 23 Buckingham Palace.........................................................................................................Page -

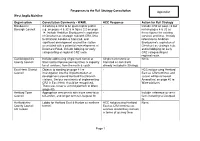

Responses to the Rail Strategy Consultation Page 1 West Anglia

Responses to the Rail Strategy Consultation Appendix1 West Anglia Mainline Organisation Consultation Comments - WAML HCC Response Action for Rail Strategy Broxbourne 4-tracking & CR2 to be given higher profile - Include CR2 on page 14 but Borough Council e.g. on pages 4 & 32 & in figure 2.2 on page not on pages 4 & 32 as 14. Include Ambition Broxbourne's aspiration these figures list existing of Cheshunt as strategic hub with CR2, links services and lines. Include to Stratford, London & Stansted, and reference to Ambition significant development around the station Broxbourne's aspiration of associated with a potential redevelopment of Cheshunt as strategic hub, Delamare Road. Include lobbying for early and of lobbying for early safeguarding of regional CR2 route. CR2 safeguarding of regional route. Cambridgeshire Include addressing single track tunnel at Single track tunnel at None. County Council Stansted to improve journey times & capacity Stansted as constraint for all services, from the north & south. already included in Strategy. East Herts District Objects to wording on page 41 re - HCC not pursuing Hertford Council investigation into the implementation of East as CR2 terminus and development around Hertford East branch so text will be removed. stations. Serious constraints of implementing Amend text on page 40 re CR2 in East Herts should be recognised. Ware platform. There was never a second platform at Ware (page 40). Hertford Town Appropriate service mix with more semi-fasts - Include reference to semi- Council to London, and longer term to Liverpool St. fasts including to Liverpool St. Hertfordshire Lobby for Hertford East & Harlow as northern HCC not pursuing Hertford None. -

Response to the Consultation Document

RESPONSE TO THE CONSULTATION DOCUMENT: “A new approach to rail passenger services in London and the South East” Introduction 1. This response from concentrates on matters affecting the users of the four stations on the Greenwich line (Deptford, Greenwich, Maze Hill, and Westcombe Park). We do not comment on matters that only affect other areas of London and the South East. 2. Our response also takes account of the announcement made on 21 January 2016 that responsibility “for inner London rail services that operate wholly or mainly within Greater London” will transfer to TfL. The precise services or geographical area are not specified, but, for the purposes of our response about services on this line, we have assumed it includes all our trains except for a few peak hour services that extend beyond Dartford 3. Latest ORR figures of estimated station usage show that, in 2014/15, there were 7.1m users of these four stations, an increase of 5.5% over the previous year. This number will certainly continue to rise as a result of large housing developments in the Greenwich and Deptford area. Since 2014, 7,080 new homes have either been built, or are being built, in the vicinity of at least one of the four stations. A further 15,000 are planned for North Greenwich which will impact on Maze Hill and Westcombe Park. Greenwich is a major tourist destination for London and home to the University of Greenwich and Trinity/Laban and other educational establishments, with over 38,000 students. The proposed cruise liner terminal at Enderby’s wharf will also add pressure. -

Joint Performance Improvement Update

Joint Performance Improvement Update Period 1 (2018-19) This report gives progress on the joint improvement plan for Govia Thameslink Railway (GTR) and Network Rail with punctuality data by route, as well as the main operational issues in the period (there are 13, 4-week reporting periods per year), and planned customer improvements. PPM* statistics and delay responsibility by route – Period 1 (to 28 April 2018) Gatwick Express Great Northern Southern Thameslink *The public performance measure (PPM) data above shows the percentage of trains which arrive at their terminating station within five minutes of the planned arrival time. It combines figures for punctuality and reliability into a single performance measure. A summary of key issues affecting performance in this period In period 1, GTR’s PPM was 85.2% with the main incidents affecting performance being the emergency services dealing with incidents near South Croydon on 7 and 19 April, these services dealing with an incident near Cricklewood on 3 April, a track circuit failure near Hornsey on 19 April and a vehicle striking a bridge near East Croydon on 11 April. The PPM for each of the brands for this period was: Gatwick Express 79.01%, Great Northern 87.33%, Southern 83.49% and Thameslink 89.33%. Delivering improvements for passengers Thameslink Class 700s There are 71 class 700 trains in regular service between Brighton and London Bridge or Bedford; between Wimbledon, Sutton, St Albans and Luton; on the Sevenoaks route and between Horsham / Littlehampton and London. Performance Strategy Huge investment is being put into the railway which will ultimately deliver more capacity through new and longer trains at the end of the Thameslink programme in 2018, as well as a transformed station at London Bridge. -

London Guide Welcome to London

Visitor information Welcome to London Your guide to getting around central London on public transport and making the most of your visit. tfl.gov.uk/visitinglondon Tube and central London bus maps inside #LondonIsOpen Welcome to London Paying for your travel Public transport is the best way to get There are different ways to pay for your around London and discover all that the travel. For most people, pay as you go - city has to offer. This guide will help you paying for the trips you make - with a plan how to get around the Capital on contactless payment card, an Oyster card or public transport. a Visitor Oyster card, is the best option as it If you have just arrived at an airport and are offers value, flexibility and convenience. looking for ways to get to central London, go to page 11 in this guide. Getting around London London’s transport system is iconic. With its world famous Underground (Tube) and iconic red buses, travelling around the Capital is an experience in itself. But London is much more than just the Tube or the bus; our vast network of transport services includes: Contactless payment cards If your credit, debit, charge card or wearable device has the contactless symbol above you can use it for pay as you go travel on London’s public transport. Android Pay and Apple Pay are also accepted. Benefits of contactless • It’s quick and easy – there’s no need to queue to buy a ticket • It offers great value – pay as you go with contactless is better value than buying a single ticket and you can benefit from both Night Tube daily and weekly capping (see page 5) • 14 million people have used contactless Night Tube services run on the to travel in London – including customers Jubilee, Victoria and most of from over 90 countries the Central and Northern lines all night on Fridays and Saturdays. -

Photographs in Bold Acacia Avenue 64 Ackroyd, Peter 54 Alcohol 162–3 Aldgate 12 Ashcombe Walker, Herbert 125 Ashford In

smoothly from harrow index Cobb, Richard 173 Evening Standard 71, 104 INDEX Coffee 148–9 Fenchurch Street station 50, 152, 170 Collins, Wilkie 73 Film 102, 115 Conan Doyle, Arthur 27 Fleet line 210 Photographs in bold Conrad, Joseph 138 Food 146–7, 162. 188, 193 Cornford, Frances 78 Forster, EM 212 Acacia Avenue 64 Blake, William 137 Cortázar, Julio 163 Freesheets (newspapers) 104 Ackroyd, Peter 54 Bond, James 25, 102, 214 Crash (novel) 226 Freud, Sigmund 116, 119 Alcohol 162–3 Bowie, David 54, 55, 56, 90 Crossrail 204 Frisch, Max 13 Aldgate 12 Bowlby, Rachel 191 Cufflinks 156 Frotteurism 119 Ashcombe Walker, Herbert 125 Bowler hat 24 Cunningham, Gail 112 Fulham 55 Ashford International station 121 Bridges, in London 12, 32, 101, 154 Cyclist see Bicycles Gaiman, Neil 23 Austen, Jane 59 Briefcase 79 Dagenham 198 Galsworthy, John 173 Baker Street station 168, 215 Brighton 54 Dalston 55 Garden Cities 76–7, 106, 187 Balham station 134 Brixton 55 Davenant, William 38 Good Life, The (TV series) 54, 59, 158 Ball, Benjamin 116 Bromley 55 Davies, Ray 218 Guildford 64, 206 Ballard, JG 20, 55, 72, 112, 226 Bromley-by-Bow station 102, 213 De Botton, Alain 42, 110, 116 Great Missenden 60–1 Banbury 127 Buckinghamshire 20, 54, 57, 64 Deighton, Len 41 Green, Roger 16, 96, 229 Bank station 138, 152, 153 Burtonwood 36 De La Mare, Walter 20 Hackney 8, 13, 65, 121 Barker, Paul 54, 56, 81 Buses 15, 41, 111, 115, 129, 130, Derrida, Jacques 117 Hamilton, Patrick 114 Barking 213 134, 220–1 Diary of a Nobody, The 11, 23, 65, 195 Hampstead 54, 58, 121 Barnes, Julian -

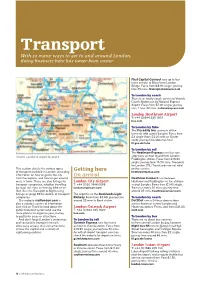

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

Passenger Focus' Response to C2c's Proposed Franchise Extension July

Passenger Focus’ response to c2c’s proposed franchise extension July 2008 Passenger Focus – who we are and what we do Passenger Focus is the independent national rail consumer watchdog. It is an executive non- departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Transport. Our mission is to get the best deal for Britain's rail passengers. We have two main aims: to influence both long and short term decisions and issues that affect passengers and to help passengers through advice, advocacy and empowerment. With a strong emphasis on evidence-based campaigning and research, we ensure that we know what is happening on the ground. We use our knowledge to influence decisions on behalf of rail passengers and we work with the rail industry, other passenger groups and Government to secure journey improvements. Our vision is to ensure that the rail industry and Government are always ‘putting rail passengers first’ This will be achieved through our mission of ‘getting the best deal for passengers’ 1 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Executive summary 3 3. Response to DfT consultation document 4 4. Appendix A: summary of consultation responses 10 5. Contact details 12 2 1. Introduction Passenger Focus welcomes the opportunity to comment on the Department for Transport’s (DfT) consultation on the proposal to extend c2c’s franchise by two years. Although the consultation process has not been formally set out we were aware of informal discussions for an extension since last year. We view the extension proposal as a very good opportunity for the c2c franchise to be revitalised with a fresh mandate to develop and improve operational performance as well as customer services. -

C2C Train Time Schedule & Line Route

C2C train time schedule & line map Barking View In Website Mode The C2C train line (Barking) has 10 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Barking: 12:19 AM - 11:55 PM (2) Grays: 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM (3) Laindon: 6:56 AM - 7:52 AM (4) Leigh-On-Sea: 12:11 AM - 4:57 PM (5) London Fenchurch Street: 4:06 AM - 11:39 PM (6) London Liverpool Street: 8:26 AM - 9:56 PM (7) Pitsea: 6:08 AM - 11:41 PM (8) Shoeburyness: 12:34 AM - 11:29 PM (9) Southend Central: 4:53 AM - 11:58 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest C2C train station near you and ƒnd out when is the next C2C train arriving. Direction: Barking C2C train Time Schedule 5 stops Barking Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:19 AM - 11:55 PM Monday Not Operational Grays Station Approach, Grays Tuesday Not Operational Chafford Hundred Wednesday Not Operational Ockendon Thursday Not Operational Friday Not Operational Upminster Hall Lane, London Saturday Not Operational Barking Station Parade, London C2C train Info Direction: Barking Stops: 5 Trip Duration: 26 min Line Summary: Grays, Chafford Hundred, Ockendon, Upminster, Barking Direction: Grays C2C train Time Schedule 8 stops Grays Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:17 AM - 11:11 PM Monday 5:20 AM - 11:55 PM Fenchurch Street 43-44 Crutched Friars, London Tuesday 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM Limehouse Wednesday 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM 26 Flamborough Street, London Thursday 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM West Ham Friday 12:25 AM - 11:55 PM 4a Memorial Avenue, London Saturday 12:25 AM - 11:59 PM Barking Station Parade, London -

Hampton Court to Berrylands / Oct 2015

Crossrail 2 factsheet: Services between Berrylands and Hampton Court New Crossrail 2 services are proposed to serve all stations between Berrylands and Hampton Court, with 4 trains per hour in each direction operating directly to, and across central London. What is Crossrail 2? Crossrail 2 in this area Crossrail 2 is a proposed new railway serving London and the wider South East that could be open by 2030. It would connect the existing National Rail networks in Surrey and Hertfordshire with trains running through a new tunnel from Wimbledon to Tottenham Hale and New Southgate. Crossrail 2 will connect directly with National Rail, London Underground, London Overground, Crossrail 1, High Speed 1 international and domestic and High Speed 2 services, meaning passengers will be one change away from over 800 destinations nationwide. Why do we need Crossrail 2? The South West Main Line is one of the busiest and most congested routes in the country. It already faces capacity constraints and demand for National Rail services into Waterloo is forecast to increase by at least 40% by 2043. This means the severe crowding on the network will nearly double, and would likely lead to passengers being unable to board trains at some stations. Crossrail 2 provides a solution. It would free up space on the railway helping to reduce congestion, and would enable us to run more local services to central London that bypass the most congested stations. Transport improvements already underway will help offset the pressure in the short term. But we need Crossrail 2 to cope with longer term growth. -

Railways: Thameslink Infrastructure Project

Railways: Thameslink infrastructure project Standard Note: SN1537 Last updated: 26 January 2012 Author: Louise Butcher Section Business and Transport This note describes the Thameslink infrastructure project, including information on how the scheme got off the ground, construction issues and the policy of successive government towards the project. It does not deal with the controversial Thameslink rolling project to purchase new trains to run on the route. This is covered in HC Library note SN3146. The re- let of the Thameslink passenger franchise is covered in SN1343, both available on the Railways topical page of the Parliament website. The Thameslink project involves electrification, signalling and new track works. This will increase capacity, reduce journey times and generally expand the current Thameslink route through central London and across the South East of England. On completion in 2018, up to 24 trains per hour will operate through central London, reducing the need for interchange onto London Underground services. The project dates back to the Conservative Government in the mid-1990s. It underwent a lengthy public inquiry process under the Labour Government and has been continued by the Coalition Government. However, the scheme will not be complete until 2018 – 14 years later than its supporters had hoped when the scheme was initially proposed. Contents 1 Where things stand: Thameslink in 2012 2 2 Scheme generation and development, 1995-2007 3 2.1 Transport and Works Act (TWA) Order application, 1997 5 2.2 Revised TWA Order application, 1999 6 2.3 Public Inquiry, 2000-2006 6 2.4 New Thameslink station at St Pancras 7 This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual.