The Onset of the Palaeoanthropocene in Iceland: Changes to Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A B ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 358 architecture 19, 316 Grímsey 202 Arctic Fox Center 171 Heimaey Arctic Fox Research Station 171 Hrísey 201 Arctic foxes 35, 37, 171, 276, 311, 36 Ingólfshöfði 276 Arctic Henge 234-5 Krýsuvíkurberg 94 Arctic terns 312 Látrabjarg 162 Ari the Learned 303, 323 Mývatn region 222-3 Arnarson, Ingólfur 46 Papey 261 Arnarstapi 153-4 Reykjavík 52 Arnarvatnsheiði 142 Sandgerði 93 Árnes (Norðurfjörður) 178 Skálanes 255 Árnes (Þjórsárdalur) 101-2 Skrúður 259 Árskógsströnd 201 Snæfellsjökull National Park 152 100 Crater Park 93 arts 315-20 Stykkishólmur 143 101 Reykjavík 316, 318 Ásatrú 324-5 Viðey 80 4WD tours 227, 236, 242, 282 Ásbyrgi 232-3 Bjarkalundur 159 Áshöfði 233 Bjarnarfjörður 177 Bjarnarflag 223-4 A Askja 217, 294-5, 293 Bjarnarhöfn 148-9 accommodation 20, 332-5, see also Askja Way 292-5 individual locations Ásmundarsafn 50 Björk 317 activities 22, 24, 32-8, see also ATMs 339 Bláa Kirkjan 251 individual activities aurora borealis 9, 25, 37, 59, 9, 179 Bláfjöll 57 Aðalból 247 Austurengjar 94 Blue Lagoon 6, 58, 88-9, 6-7 Age of Settlement 301 Austurvöllur 49 Blönduós 191-2 air travel 344, 345 boat tours, see also kayaking Akranes 135, 138 Heimaey 131-2 B Akureyri 203-15, Hvítárvatn 288-9 204-5 Baðstofa 153 accommodation 209-11 Ísafjörður 167-8 Bakkagerði 247-50 activities 207-9 Jökulsárlón 277 Bárðarlaug 153 drinking 212-13 Stykkishólmur 144-5 Básendar 93 emergency services 213 boat travel 345, 346 beaches entertainment 213 boating 32-3 Breiðavík 162 festivals 209 Bolungarvík 170 Hvallátur 162 food 211-12 -

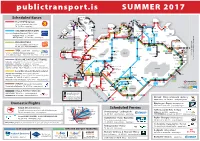

Public Transport Summer 2017 in English

publictransport.is SUMMER 2017 Hornstrandir Area Scheduled Buses Hornvík Bolungarvík Grímsey The STRÆTÓ System Kópasker Raufarhöfn Hnífsdalur Dranga- Reykjar- Siglufjörður jökull Flatey This is the main public bus system Ísafjörður Vigur fjörður 78 641 Drangey Tel. 540 2700 - www.bus.is Suðureyri Súðavík Hrísey Norður- Ólafs- 79 Flateyri fjörður Skagaströnd Reykir Hofsós fjörður Ásbyrgi 650 Húsavík Þórshöfn Þingeyri 84 85 Dalvík Reykjanes Gjögur Hólar ICELAND ON YOUR OWN Bíldudalur Crossroads Sauðárkrókur Árskógssandur Aðaldalsvegur Hljóðaklettar & Hauganes Operated by Reykjavik Excursions & SBA-Norðurleið Tálknafjörður Skriðuland 650 641 85 Dettifoss Patreksfjörður Islands) (Faroe Tórshavn LINE to SMYRIL Reykjavik Office: Tel. 580 5400 Örlygshöfn 59 Hólmavík 661 Vopnafjörður Blönduós 84 Akureyri FnjóskárbrúNorðaustur- Brjánslækur vegur 79 Akureyri Office: Tel. 550 0700 - www.ioyo.is Fosshóll Krafla Látrabjarg Rauðasandur Hvammstangi Varmahlíð 57 60 661 Víðigerði 56 79 5 Svartá and Hirtshals (Denmark) 83 Króks- 62 641 Einarsstaðaskáli Jökulsá fjarðarnes Hvammstangavegur Laugar Vopnafjörður Borgarfjörður eystri ICELAND BY BUS Flatey Crossroads 62 á Fjöllum Crossroads Skriðuland 610 Skjöldólfs- Operated by Sterna & SBA-Norðurleið staðir Skútu- Fella- Seyðis- Tel. 551 1166 - www.icelandbybus.is Staðarskáli Mývatn Dettifoss Búðardalur staðir Crossroads bær fjörður r Hveravellir Aldeyjarfoss 650 661 k fjörður 57 60 3 issandu ví r Stykkishólmur 14 17 Norðfjörður TREX Tel. 587 6000 - www.trex.is Hell Rif Ólafs 82 58 59 1 Grunda Kerlingar- 62 62 56 1 Bifröst fjöll ASK 1 Services to Þórsmörk (Básar and Langidalur) Hofsjökull Eskifjörður Vatnaleið Herðubreiðarlindir Egilsstaðir Snæfells- Baula Langjökull Hvítárnes and Landmannalaugar. Summer schedule 15 June - 24 Sept. 2017 jökull Crossroads Reyðar- fjörður 2 Vegamót Reykholt Nýidalur Askja 82 Arnar- 58 81 Kleppjárnsreykir 6 Gullfoss 14 Fáskrúðsfjörður stapi 17 MAIN LINES IN THE WESTFJORDS Borgarnes Hvanneyri Laugarvatn Geysir Stöðvarfjörður Ísafjörður – Hólmavík: Tel. -

ICELAND 2006 Geodynamics Field Trip May 30 – June 8, 2006

ICELAND 2006 Geodynamics Field Trip May 30 – June 8, 2006 Massachusetts Institute of Technology/ Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program in Oceanography This field trip guide was compiled by Karen L. Bice using information from Bryndís Brandsdóttir, Richard S. Williams, Helgi Torfason, Helgi Bjornsson, Oddur Sigurðsson, the Iceland Tourist Board and World W. Web Maps from Thordarson and Hoskuldsson, 2002, Iceland (Classic Geology in Europe 3), Terra Publishing, UK. Logistical genius: Andrew T. Daly Field trip participants: Mark Behn, Karen Bice, Roger Buck, Andrew Daly, Henry Dick, Hans Schouten, Martha Buckley, James Elsenbeck, Pilar Estrada, Fern Gibbons, Trish Gregg, Sharon Hoffmann, Matt Jackson, Michael Krawczynski, Christopher Linder, Johan Lissenberg, Andrea Llenos, Rowena Lohman, Luc Mehl, Christian Miller, Ran Qin, Emily Roland, Casey Saenger, Rachel Stanley, Peter Sugimura, and Christopher Waters The Geodynamics Program is co-sponsored by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Academic Programs Office and Deep Ocean Exploration Institute. TUESDAY May 30 Estimated driving (km) Meet at Logan Airport, Icelandair ticket counter @ 7:00 PM (80 km ≈ 50 mi) Depart BOS 9:30 PM Icelandair flight Day 1 - WEDNESDAY May 31 Arrive Keflavík International Airport 6:30 AM (flight duration 5 hours) Pick up 2 vans, 2 trailers (Budget) Free day in Reykjavík Night @ Laugardalur campground, Reykjavík Dinner: on own in town Day 2 - THURSDAY June 1 270 Late start due to trailer problems (2 hrs @ AVIS) To Þingvellir N.P., then north to Hvalfjörður fjord, stop at Skorradalsvatn Night @ Sæberg Hostel (1 km. off Rte 1 in Hrútafjörður, west side of road) Tel. 354-4510015 Fax. 354-4510034 [email protected] Dinner: mexican-style chicken (Rachel, Trish, Chris) Day 3 - FRIDAY June 2 320 To Lake Myvatn Lunch stop in Akureyri, stop at Godafoss, stop at Skutustadir pseudocraters Night @ Ferdathjonustan Bjarg campsite, Reykjahlid, on shore of Lake Myvatn Tel. -

Publictransport.Is 2020 Personen

Öffentliche Linienbusse STRÆTÓ (ganzjährig) Dies ist das öffentliche Busnetz in Island 2020 publictransport.is Tel. 540 2700 - www.bus.is SVAUST Bussystem der Ostfjorde (ganzjährig) Hornstrandir-Gebiet Tourist Info in Egilsstaðir: Tel. 471 2320 - www.svaust.is Hornvík Bolungarvík Grímsey Tourist Info in Seyðisfjörður: Tel. 472 1551 - www.visitseydisfjordur.com Raufarhöfn Hnífsdalur Dranga- Reykjar- Siglufjörður Ísafjörður jökull Kópasker Vigur fjörður 78 Flatey Lokale Busse in West-Island (ganzjährig) Suðureyri Drangey Hrísey 79 Súðavík Norður- Ólafs- Bolungarvík - Ísafjörður (Flughafen): Tel. 893 8355 - www.bolungarvik.is A fjörður Húsavík Flateyri fjörður Skagaströnd Hofsós Ásbyrgi Þórshöfn Ísafjörður – Suðureyri – Flateyri – Þingeyri: Tel. 893 6356 - www.isafjordur.is Þingeyri 84 Dalvík Heydalur Gjögur Hólar Grenivík Kreuzung Patreksfjörður - Bíldudalur: Tel. 456 5006 & 848 9614 - www.vesturbyggd.is Bíldudalur Sauðárkrókur Árskógssandur Hljóðaklettar & Hauganes Aðaldalsvegur Patreksfjörður - Bíldudalur Flughafen: Tel. 893 0809 & 893 2636 - vesturbyggd.is Tálknafjörður Dynjandi Reykjanes Drangsnes ú r- Grímsey und Hirtshals (Dänemark) (Färöer) Tórshavn Skriðuland br tu Hellissandur - Rif - Ólafsvík: Tel. 433 6900 & 892 4327 - www.snb.is Patreksfjörður Flókalundur ár s ur sk au eg Dettifoss ó rð v B A 59 Hólmavík nj o Vopnafjörður Westfjords Tourist Information: Tel. 450 8060 - www.westfjords.is Blönduós 84 Akureyri F N Brjánslækur Látrabjarg Rauðasandur B Hvammstangi Víðigerði Varmahlíð 57 78 56 79 Krafla 5 nach LINE - Fähre SMYRIL Svartá -

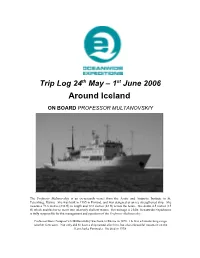

Around Iceland

Trip Log 24th May – 1st June 2006 Around Iceland ON BOARD PROFESSOR MULTANOVSKIY The Professor Multanovskiy is an ex-research vessel from the Arctic and Antarctic Institute in St. Petersburg, Russia. She was built in 1985 in Finland, and was designed as an ice strengthened ship. She measures 71.6 metres (236 ft) in length and 12.8 metres (42 ft) across the beam. She draws 4.5 metres (15 ft) which enables her to move into relatively shallow waters. Her tonnage is 2140t. Oceanwide Expeditions is fully responsible for the management and operation of the Professor Multanovskiy. Professor Boris Pompeevich Multanovskiy was born in Russia in 1876. He was a famous long-range weather forecaster. Not only did he have a ship named after him, but also a beautiful mountain on the Kamchatka Peninsula. He died in 1938. With Captain Igor Stetsun and his crew of 19 from St. Petersburg, Russia Expedition Leader: Rolf Stange (Geographer), Germany Guide/Lecturer: Dagný Indriđadóttir (Folklorist), Iceland Guide/Lecturer: Ian Stone (Historian), Isle of Man Purser: Juliette Corssen, Germany Chefs: Jocelyn Wilson, New Zealand & Gerd Brenner, Germany Doctor: Johannes Schön, Germany 24th May - Embarkation in Keflavík, Faxaflói Bay 4 pm: Position: 64º00N: 22º36W, partly sunny, strong wind. Most of us arrived in due time for embarkation at 4 pm. on a blustery day in Iceland. Many anxious eyes were cast seawards but were consoled by the remarks that we overheard that the weather seemed to be improving! Our Expedition Leader, Rolf Stange from Germany welcomed us on board the Professor Multanovskiy and introduced the staff to us. -

The Best of Iceland

04_178416-ch01.qxp 5/29/08 8:59 AM Page 1 1 The Best of Iceland On each trip to Iceland, we are always struck by how often other travelers are—or intend to be—repeat visitors. Many come year after year, never exhausting Iceland’s endless variations of magnificent scenery and adventure. Returning travelers immedi- ately recognize the crisp, invigorating polar air, and what W. H. Auden called “the most magical light of anywhere on earth.” Iceland’s astonishing beauty often has an austere, primitive, or surreal cast that arouses reverence, wonderment, mystery, and awe. Lasting impressions could include a lone tuft of wildflowers amid a bleak desert moonscape or a fantastical promenade of icebergs calved into a lake from a magisterial glacier. The Icelandic people—freedom-loving, egalitarian, self-reliant, and worldly—are equally exceptional. They established a parliamentary democracy over a millennium ago, and today write, publish, purchase, and read more books per capita than any peo- ple on earth. Reykjavík, their capital, has become one of the world’s most fashionable urban hot spots. In November 2007, the U.N. named Iceland the world’s best coun- try to live in, based on life expectancy, education levels, medical care, income, and other criteria. 1 The Best Natural Wonders • Glymur: Iceland’s tallest waterfall is • Blue Lagoon: The central activity nimble and graceful: Streamlets at this spa—Iceland’s top tourist descend like ribbons of a maypole attraction—is bathing in a shallow, into a fathomless canyon mantled in opaque, blue-green lagoon amid a bird nests and lush mosses. -

243 Comments on Sveinbjörnsdóttir Et Al. (2004) And

RADIOCARBON, Vol 48, Nr 2, 2006, p 243–252 © 2006 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona COMMENTS ON SVEINBJÖRNSDÓTTIR ET AL. (2004) AND THE SETTLEMENT OF ICELAND Ingrid U Olsson Department of Physics, University of Uppsala, Box 530, SE-751 21 Uppsala, Sweden. Email: [email protected]. ABSTRACT. Radiocarbon dates on samples aimed to date the settlement of Iceland are given together with comments by the laboratory, since many of the results and descriptions given by Sveinbjörnsdóttir et al. (2004) in Radiocarbon, together with new results, are in error. The intention of this paper is to present correct dates and further relevant information regarding sam- ples used earlier and to discuss possible complications inherent in the method of Sveinbjörnsdóttir et al. (2004). Examples are given of how critical the collection, treatment, and interpretation of samples may be. An age difference between birch char- coal and grains for a site is expected due to various reasons. If the difference amounts up to ~100 yr, as reported by Sveinb- jörnsdóttir et al. (2004), it must only to a small degree be due to biological age. Reference to an excavation report, details regarding stratigraphy, and discussions of the risk for displacement and contamination are missing in their paper. A final eval- uation of the time for settlement should not be done until more research is completed and other possible or earlier suggested or even dated sites are discussed. A summary is given of the research on the island and volcanic effects on the 14C activity of the atmospheric CO2, especially over Iceland. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 411 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feed- back goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. OUR READERS Alexis Averbuck My work on Iceland was a labour of love supported Many thanks to the travellers who used the last by many. Big thanks to Heimir Hansson (Westfjords), edition and wrote to us with helpful hints, useful Jón Björnsson (Hornstrandir), Dagný Jóhannsdóttir advice and interesting anecdotes: Anna Brunner & Jessica Brooke, Bart Streefkerk, Cliff & Helen Elsey, (Southwest), Kristján Guðmundsson (West), Rag- Daniel Crouch, Elena Kagi, Eyþór Jóvinsson, Fiorella nheiður Sylvía Kjartansdóttir (Reykjavík and every- Taddeo, Gudrun Stefansdottir, Helen Simpson, Ildiko where!), Einar Sæmundsen (Þingvellir) and Helga Lorik, Janire Echevarri, John Gerrard, John Malone, Garðarsdóttir (Laugavegurinn). -

Power to the People Isavia – New Master Plan for the Growing Tourism Explore Greenland‘S Idyllic Nature Vast Volcanic Hot Spots

TOURISM, CULT URE AND BUSINESS ISSUE 33 • 2016 ISSUE 33 • 2016 Power to the people Isavia – New master plan for the growing tourism Explore Greenland‘s idyllic nature Vast volcanic hot spots 1 www.icelandictimes.com Daily horse theater at 7 pm Live presentation daily at 1 pm and 4.30 pm Barn tour every 30 minutes 3 GRANDAGARÐI 8 101 REYKJAVwww.icelandictimes.comÍK * 00354 456 4040 * WWW.BRYGGJANBRUGGHUS.IS TOURISM, CULT URE AND BUSINESS ISSUE 33 • 2016 Take part in a great adventure. t’s a sad testimony of today’s society that the political and banking elite It was ironic that the country with the seem to feel that they alone know what is best for the world, leaving world’s longest running parliament should the general public to submissively follow their dictates, even if that be the one to stand up for democracy to leads to disastrous decisions and a dramatic decline in living standards. bring power back to the people. IWhen one man stood up for what was right for his country and let Building on his belief that the people the people decide on a major issue, he unleashed a torrent of criticism had an important part to plan in deciding from that international elite and the media they control. However, he was the world’s future, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson proven both ethically and legally correct in the court case that ensued. announced the founding of Arctic Circle in That man was the President of Iceland, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson and Spring 2013. the the event was the collapse of one of its private banks in the Icesave Icelandic Times has an in-depth interview and review of the man Inside Volcano debacle in 2008. -

Stofnvöktun Lunda 2018

STOFNVÖKTUN LUNDA 2018 Framvinduskýrsla til Umhverfisstofnunar Erpur Snær Hansen Desember 2018 Stofnvöktun lunda – Framvinduskýrsla 2018 ÁGRIP Lundi er algengastur og mest veiddur íslenskra fugla. Næstum allur lundi er nú veiddur í háf á varptíma og varð háfaveiði ríkjandi veiðiaðferð í Vestmannaeyjum um 1880 [1]. Þar hefur veiðimagn verið tengt sjávarhita frá 1880 [2]. Skiptast á hlý- og köld tímabil sem vara í um 35 ár, og hefur veiði hnignað á hlýskeiðunum en aukist á kaldskeiðum [2]. Núverandi hlýskeið hófst 1996 og hefur veiði á landsvísu dregist saman um 91% síðan 1995, en samdrátturinn 1995-2007 nemur 66 prósentustigum, þ.e. áður en dregið var úr sókn. Viðkoma, varpárangur og ábúð varphola hefur verið mjög breytileg milli fjögurra skilgreindra landsvæða, hæst á norðursvæði og fremur stöðug milli ára. Á Vestursvæði hafa orðið mestar breytingar, en þar hefur viðkoma, varpárangur og ábúð aukist mikið þar til síðustu tvö ár að bakslag hefur komið. Sandsíli hefur talsvert sést í fæðuburði síðust tvö ár, mest í Faxaflóa. Svo virðist sem sílið nái ekki að fjölga nægjanlega mikið til að ná fyrri stöðu sinni. Í Papey hefur viðkoma, varpárangur og ábúð verið á hægri niðurleið eftir núll-árin 2010 og 2011. Meðal viðkoma og varpárangur hafa verið lægst í Vestmannaeyjum, en meðal ábúð hin sama og á vestursvæði eða 25-30% lægri en á norður- og austursvæðunum. Viðkoma í Eyjum hefur verið svo lítil allt frá árinu 2003 að íslenski lundastofninn hefur verið í rénun síðan þá. Hlutfall ungfugla í veiði 1996-2018 hefur verið tölfræðilega marktækt undir viðmiðunarmörkum, en aukist verulega síðustu tvö ár. -

PT 2019 Þýska

Linienbusse STRÆTÓ (ganzjährig) Dies ist das öffentliche Busnetz in Island 2019 publictransport.is Tel. 540 2700 - www.bus.is SVAUST Bussystem der Ostfjorde (ganzjährig) Hornstrandir-Gebiet Tourist Info in Egilsstaðir: Tel. 471 2320 - www.svaust.is Hornvík Tourist Info in Seyðisfjörður: Tel. 472 1551 - www.visitseydisfjordur.com Bolungarvík Grímsey Hnífsdalur Dranga- Reykjar- Siglufjörður Ísafjörður jökull Lokale Busse in West-Island (ganzjährig) Vigur fjörður 78 Flatey Bolungarvík - Ísafjörður (Flughafen): Tel. 893 8355 - www.bolungarvik.is Suðureyri Drangey Hrísey 79 Súðavík Norður- Ólafs- Ísafjörður – Suðureyri – Flateyri – Þingeyri: Tel. 893 6356 - www.isafjordur.is fjörður fjörður Húsavík Flateyri Skagaströnd Hofsós 85 Þórshöfn Patreksfjörður - Bíldudalur: Tel. 456 5006 & 848 9614 - www.vesturbyggd.is Þingeyri 84 Dalvík Heydalur Gjögur Hólar Patreksfjörður - Bíldudalur Flughafen: Tel. 893 0809 & 893 2636 - vesturbyggd.is Kreuzung Bíldudalur Sauðárkrókur Árskógssandur Aðaldalsvegur Hellissandur - Rif - Ólafsvík: Tel. 433 6900 & 892 4327 - www.snb.is Tálknafjörður Dynjandi Reykjanes Drangsnes & Hauganes Grímsey 85 Skriðuland und Hirtshals (Dänemark) (Färöer) Tórshavn Westfjords Tourist Information: Tel. 450 8060 - www.westfjords.is Flókalundur Patreksfjörður 59 Hólmavík Vopnafjörður Blönduós 84 Akureyri FnjóskárbrúNorðaustur- Brjánslækur vegur Látrabjarg Rauðasandur Hvammstangi Víðigerði Varmahlíð 57 78 56 79 Svartá 5 nach LINE - Fähre SMYRIL 610 Goðafoss Króks- 83 (Fosshóll) Laugar fjarðarnes Hvammstangavegur Jökulsá Vopnafjörður Kreuzung Mývatn á Fjöllum Kreuzung Borgarfjörður Touristische Linienbusse Flatey eystri 610 Nur im Sommer, mit Reservierung Skriðuland Skútu- 3 staðir ASK Staðarskáli Skjöldólfs- 1 5 3 Seyðisfjörður r Búðardalur Hveravellir staðir (Betrieb 2019 unsicher) Fernbusse in den Westfjorden k Stykkishólmur ví rfjörður 57 Ísafjörður – Hólmavík: Tel. 450 8060 - www.westfjords.is issandu 82 58 Fellabær 56 Neskaupstaður 1 Hell Rif Ólafs Kerlingar- 82 Grunda 59 Reyðarfjörður Patreksfjörður – Brjánslækur – Ísafjörður: Tel. -

Radiocarbon Dating and Icelandic Archaeology

RADIOCARBON DATING AND ICELANDIC ARCHAEOLOGY Vilhjdlmur örn Vilhjrilmsson ABSTRACT This article deals with the application of radiocarbon dating in Icelandic archaeology. Results of some of the raC datings do not match the conventional date for the settlement of Iceland. An attempt has been made to explain this discrepancy by a reservoir effect- hypothesis which has neither been sufficiently tested nor proven. Most of the irregular dates derive notably from a single laboratory. A number of alternative explanations for the discrepancy are given in this study, among them the fact that some radiocarbon laboratories do not ask for, or execute, a detailed wood-analysis prior to dating. Introduction archaeologists and geologists have not alwaysunder- stood the character of the method, its inaccuracy and all the possible pitfalls which have to be taken into Most Icelandic lac dating samples have been handed account, before results a radiocarbon date are in at laboratories with the hope that the dates they of presented. will provide are consistent with the traditional date for the settlement of Iceland (Icel. I-andndm), at the end of the ninth cantury. Unfortunately, neither the The landnam t4C dating method, nor the samples, have been able to provide definite proof for the traditional literary The settlement of Iceland has played an important, date of the landnam. If not questioned, a number of and maybe an over-important role for much research dating results have turned out to indicate a settle- in Iceland, both within literary and scientif,rc research ment in Iceland somewhat earlier than the conven- subjects. The landnam has also been the main goal tional and hitherto accepted date for the Icelandic for the people who collected raC samples in Iceland.