THE ECOLOGY of HONEYEATERS in SOUTH AUSTRALIA (A Lecture Presented to the S.A.O.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 'Slow Pace of Life' in Australian Old-Endemic Passerine Birds Is Not Accompanied by Low Basal Metabolic Rates

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2016 A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Claus Bech University of Wollongong Mark A. Chappell University of Wollongong, [email protected] Lee B. Astheimer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Gustavo A. Londoño Universidad Icesi William A. Buttemer University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Bech, Claus; Chappell, Mark A.; Astheimer, Lee B.; Londoño, Gustavo A.; and Buttemer, William A., "A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates" (2016). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 3841. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/3841 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A 'slow pace of life' in Australian old-endemic passerine birds is not accompanied by low basal metabolic rates Abstract Life history theory suggests that species experiencing high extrinsic mortality rates allocate more resources toward reproduction relative to self-maintenance and reach maturity earlier ('fast pace of life') than those having greater life expectancy and reproducing at a lower rate ('slow pace of life'). Among birds, many studies have shown that tropical species have a slower pace of life than temperate-breeding species. -

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

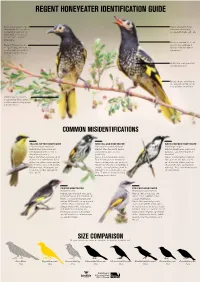

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Wellington Shire Council Implementation of Coastal Strategy Land Capability Assessment

Wellington Shire Council Implementation of Coastal Strategy Land Capability Assessment March 2008 Contents 1. Background 1 1.1 Recent Strategy and Policy Decisions 1 1.2 Current Implementation Process 1 2. Methodology 2 2.1 Initial Methodology 2 2.2 Data Availability 2 2.3 Revised Methodology 3 3. Data 4 3.1 Data Sorting 4 3.2 Critical Data Sets 4 4. Analysis 12 4.1 Stage 1: Areas Inappropriate for Additional Dwellings 12 4.2 Stage 2: Capability Assessment for Dwelling Densities 12 4.3 Assigning Capability Scores for Dwelling Densities 13 5. Findings 18 5.1 Key Constraints to Development of Dwellings 18 5.2 Implications for Current Adopted Settlement Structure 21 5.3 Implications of Land Capability Assessment 23 5.4 Utilising the Outcomes of the Land Capability Assessment 23 Appendices A Flora and Fauna Report B Landscape Assessment Report C Table of Capability Scores for Dwelling Density Scenarios D Land Capability Mapping Implementation of Coastal Strategy i Land Capability Assessment 31/20287/138968 1. Background 1.1 Recent Strategy and Policy Decisions The Wellington Shire Council adopted the Wellington Coast Subdivision Strategy Option 4 – Nodal Urban settlement pattern at its meeting of 20th September, 2005 and the preparation of the Wellington Coast Subdivision Strategy: The Honeysuckles to Paradise Beach was finalised in February 2007. The Strategy was developed in accordance with the relevant coastal planning and management principles of the Victorian Coastal Strategy, 2002 prepared by the Victorian Coastal Council, and the Gippsland Coastal Board’s Coastal Action Plans. This strategy provides a preferred settlement structure for the Wellington Coast between Paradise Beach and The Honeysuckles, as a way to encourage development that responds appropriately to environmental values and community needs, and is consistent with established policy in the Victorian Coastal Strategy. -

Inference of Phylogenetic Relationships in Passerine Birds (Aves: Passeriformes) Using New Molecular Markers

Institut für Biochemie und Biologie Evolutionsbiologie/Spezielle Zoologie Inference of phylogenetic relationships in passerine birds (Aves: Passeriformes) using new molecular markers Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades “doctor rerum naturalium” (Dr. rer. nat.) in der Wissenschaftsdisziplin “Evolutionsbiologie“ eingereicht an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Potsdam von Simone Treplin Potsdam, August 2006 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Ralph Tiedemann for the exciting topic of my thesis. I’m grateful for his ongoing interest, discussions, support, and confidence in the project and me. I thank the University of Potsdam for the opportunity to perform my PhD and the financial and logistical funds. This thesis would not have been possible without many institutions and people, who provided samples: University of Kiel, Haustierkunde (Heiner Luttmann and Joachim Oesert), Zoologischer Garten Berlin (Rudolf Reinhard), Tierpark Berlin (Martin Kaiser), Transvaal Museum, South Africa (Tamar Cassidy), Vogelpark Walsrode (Bernd Marcordes), Eberhard Curio, Roger Fotso, Tomek Janiszewski, Hazell Shokellu Thompson, and Dieter Wallschläger. Additionally, I thank everybody who thought of me in the moment of finding a bird, collected and delivered it immediately. I express my gratitude to Christoph Bleidorn for his great help with the phylogenetic analyses, the fight with the cluster, the discussions, and proof-reading. Special thanks go to Susanne Hauswaldt for patiently reading my thesis and improving my English. I thank my colleagues of the whole group of evolutionary biology/systematic zoology for the friendly and positive working atmosphere, the funny lunch brakes, and the favours in the lab. I’m grateful to Romy for being my first, ‘easy-care’ diploma-student and producing many data. -

Amytornis Observations on the Foraging Ecology Of

Amytornis 19 WESTER A USTRALIA J OURAL OF O RITHOLOGY Volume 3 (2011) 19-29 ARTICLE Observations on the foraging ecology of honeyeaters (Meliphagidae) at Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia Harry F. Recher 1, 2, 3* and William E. Davis Jr. 4 1 School of Natural Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Western Australia, Australia 6027 2 The Australian Museum, 6-8 College Street, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 2000 3 Current address; P.O. Box 154, Brooklyn, New South Wales, Australia 2083 4 Boston University, 23 Knollwood Drive, East Falmouth, MA 02536, USA * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Dryandra Woodland, a Class A conservation reserve, on the western edge of the Western Australian wheatbelt lacks the large congregations of nectar-feeding birds associated with eucalypt woodlands to the north and east of the wheatbelt. Reasons for this are not clear, but the most productive woodlands (Wandoo Eucalyptus wandoo ) at Dryandra are dominated by Yellow-plumed Honeyeaters ( Lichenostomus ornatus ), which exclude smaller honeyeaters from their colonies. There is also comparatively little eucalypt blossom available to nectar- feeders during winter and spring when we conducted our research at Dryandra. During winter and spring, honey- eaters are dependent on small areas of shrublands dominated by species of Dryandra (Proteaceae), with species segregated by size; the smaller species making greater use of the small inflorescences of D. sessilis and D. ar- mata , while the large wattlebirds used the large inflorescences of D. nobilis . Honeyeaters at Dryandra also use other energy-rich sources of carbohydrates, such as lerp and honeydew, and take arthropods, segregating by habi- tat, foraging behaviour, and substrate. -

Download Complete Work

© The Authors, 2016. Journal compilation © Australian Museum, Sydney, 2016 Records of the Australian Museum (2016) Vol. 68, issue number 5, pp. 201–230. ISSN 0067-1975 (print), ISSN 2201-4349 (online) http://dx.doi.org/10.3853/j.2201-4349.68.2016.1668 The Late Cenozoic Passerine Avifauna from Rackham’s Roost Site, Riversleigh, Australia JACQUELINE M.T. NGUYEN,1,2* SUZANNE J. HAND,2 MICHAEL ARCHER2 1 Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, 1 William Street, Sydney New South Wales 2010, Australia 2 PANGEA Research Centre, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia [email protected] · [email protected] · [email protected] ABstRACT. The Riversleigh World Heritage Area, north-western Queensland, is one of the richest Cenozoic deposits in Australia for passerine fossils. Most of the Riversleigh passerine remains derive from the late Cenozoic Rackham’s Roost Site. Here we describe 38 fossils from this site, which represent eight extant families of passerine birds. These fossils include the oldest records of Maluridae (fairywrens and allies), Acanthizidae (acanthizid warblers), Pomatostomidae (Australo-Papuan babblers), Petroicidae (Australasian robins), Estrildidae (estrildid finches), Locustellidae (songlarks and grassbirds) and Acrocephalidae (reed warblers) in Australia, and the oldest records globally of Maluridae, Acanthizidae, Pomatostomidae, Petroicidae and Estrildidae. The fossils also include the oldest known representatives of the major radiation Passerida sensu stricto in the Australian fossil record, indicating that the second dispersal event of this group had already occurred in this region at least by the early Pleistocene. In describing the Rackham’s Roost fossils, we have identified suites of postcranial characters that we consider diagnostic for several Australian passerine families. -

Birdlife Between Lake Tyers and Marlo, Victoria by GEORGE W

VOL. 8 (5) MARCH, 1980 147 Birdlife between Lake Tyers and Marlo, Victoria By GEORGE W. BEDGGOOD, Lindenow South, Victoria, 3866. Introduction Working in conjunction with Mrs. A. Swan and the Bird Observers Club, I have submitted an obje c:~io n and appeal against the granting of a permit for a cluster subdivision c.djacent to Lake Tyers House Road. From 1965 to 1967 inclusive and since 1976 I have been resident in East Gippsland and visited the area on a regular basis. During the eight intervening years I averaged two visits per year, usually in May, Septem ber or January, and was able to spend a full day birding in the area. Description of the Area Lake Tyers is a relatively quiet, well protected stretch of water sur rounded by forest and open grazing land. The small settlement at Lake Tyers has grown rapidly over the last decade. Lake Tyers Aboriginal Reserve is situated between Toorloo Arm and the Nowa Nowa Arm. The lake is generally cut off from the sea by a sandbar, breaking through only in times of very heavy rain and high seas. The small Toorloo Arm Scenic Reserve is one of the few remnants of the Eugenia smithii alliances in the region. Adjacent to the Princes Highway in the Tostaree and Waygara districts, land has been cleared for grazing including the Tostaree Experimental Farm, and Waygara State Forest stretches southward. The eastern boundary is the Snowy River estuary with its fertile flood plain. Lake Corringle is a shallow, very open stretch of water between the river and Ewings Marsh. -

Yellow Throat Turns 100! Editor YELLOW THROAT This Issue Is the 100Th Since Yellow Throat First Appeared in March 2002

Yellow Throat turns 100! Editor YELLOW THROAT This issue is the 100th since Yellow Throat first appeared in March 2002. To mark the occasion, and to complement the ecological focus of the following article by Mike The newsletter of BirdLife Tasmania Newman, here is a historical perspective, which admittedly goes back a lot further than a branch of BirdLife Australia the newsletter, and the Number 100, July 2018 organisation! Originally described by French ornithologist General Meeting for July Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1817, and Life Sciences Building, UTas, named Ptilotus Flavillus, specimens of Thursday, 12 July, 7.30 p.m. the Yellow-throated Matthew Fielding: Raven populations are enhanced by wildlife roadkill but do not Honeyeater were impact songbird assemblages. ‘collected’ by John Future land-use and climate change could supplement populations of opportunistic Gould during his visit predatory birds, such as corvids, resulting in amplified predation pressure and negative to Tasmania with his effects on populations of other avian species. Matt, a current UTas PhD candidate, will wife Elizabeth in 1838. provide an overview of his Honours study on the response of forest raven (Corvus This beautiful image tasmanicus) populations to modified landscapes and areas of high roadkill density in south- was part of the eastern Tasmania. exhibition ‘Bird Caitlan Geale: Feral cat activity at seabird colonies on Bruny Island. Woman: Elizabeth Using image analysis and modelling, Caitlin’s recent Honours project found that feral cats Gould and the birds of used the seabird colonies studied as a major food resource during the entire study period, and Australia’ at the native predators did not appear to have a large impact. -

Spring Bird Communities of a High-Altitude Area of the Gloucester Tops, New South Wales

Australian Field Ornithology 2018, 35, 21–29 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo35021029 Spring bird communities of a high-altitude area of the Gloucester Tops, New South Wales Alan Stuart1 and Mike Newman2 181 Queens Road, New Lambton NSW 2305, Australia. Email: [email protected] 272 Axiom Way, Acton Park TAS 7021, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Annual spring surveys between 2010 and 2016 in a 5000-ha area in the Gloucester Tops in New South Wales recorded 71 bird species. All the study area was at altitudes >1100 m. The monitoring program was carried out with involvement of a team of volunteers, who regularly surveyed 21 1-km transects, for a total of 289 surveys. The study area was within the Barrington Tops and Gloucester Tops Key Biodiversity Area (KBA). The trigger species for the KBA listing was the Rufous Scrub-bird Atrichornis rufescens, which was found to have a widespread distribution in the study area, with an average Reporting Rate (RR) of 56.5%. Another species cited in the KBA nomination, the Flame Robin Petroica phoenicea, had an average RR of 12.6% but with considerable annual variation. Although the Flame Robin had a widespread distribution, one-third of all records came from just two of the 21 survey transects. Thirty-seven bird species had RRs >4% in the study area and were distributed across many transects. Of these, 20 species were relatively common, with RRs >20%, and they occurred in all or nearly all of the survey transects. Introduction shrubs such as Banksia species (Binns 1995). -

Threatened and Declining Birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: Ii

THREATENED AND DECLINING BIRDS IN THE NEW SOUTH WALES SHEEP-WHEAT BELT: II. LANDSCAPE RELATIONSHIPS – MODELLING BIRD ATLAS DATA AGAINST VEGETATION COVER Patchy but non-random distribution of remnant vegetation in the South West Slopes, NSW JULIAN R.W. REID CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] NOVEMBER 2000 Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships A consultancy report prepared for the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service with Threatened Species Unit (now Biodiversity Management Unit) funding. ii THREATENED AND DECLINING BIRDS IN THE NEW SOUTH WALES SHEEP-WHEAT BELT: II. LANDSCAPE RELATIONSHIPS – MODELLING BIRD ATLAS DATA AGAINST VEGETATION COVER Julian R.W. Reid November 2000 CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] Project Manager: Sue V. Briggs, NSW NPWS Address: C/- CSIRO, GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] Disclaimer: The contents of this report do not necessarily represent the official views or policy of the NSW Government, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, or any other agency or organisation. Citation: Reid, J.R.W. 2000. Threatened and declining birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape relationships – modelling bird atlas data against vegetation cover. Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships Consultancy report to NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra. ii Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships Threatened and declining birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: II.