Ecology of the Ecological Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY ON PRIVATE LAND SERIES Wattles of the City of Whittlesea Over a dozen species of wattle are indigenous to the City of Whittlesea and many other wattle species are commonly grown in gardens. Most of the indigenous species are commonly found in the forested hills and the native forests in the northern parts of the municipality, with some species persisting along country roadsides, in smaller reserves and along creeks. Wattles are truly amazing • Wattles have multiple uses for Australian plants indigenous peoples, with most species used for food, medicine • There are more wattle species than and/or tools. any other plant genus in Australia • Wattle seeds have very hard coats (over 1000 species and subspecies). which mean they can survive in the • Wattles, like peas, fix nitrogen in ground for decades, waiting for a the soil, making them excellent cool fire to stimulate germination. for developing gardens and in • Australia’s floral emblem is a wattle: revegetation projects. Golden Wattle (Acacia pycnantha) • Many species of insects (including and this is one of Whittlesea’s local some butterflies) breed only on species specific species of wattles, making • In Victoria there is at least one them a central focus of biodiversity. wattle species in flower at all times • Wattle seeds and the insects of the year. In the Whittlesea attracted to wattle flowers are an area, there is an indigenous wattle important food source for most bird in flower from February to early species including Black Cockatoos December. and honeyeaters. Caterpillars of the Imperial Blue Butterfly are only found on wattles RB 3 Basic terminology • ‘Wattle’ = Acacia Wattle is the common name and Acacia the scientific name for this well-known group of similar / related species. -

Supplementary Materialsupplementary Material

10.1071/BT13149_AC © CSIRO 2013 Australian Journal of Botany 2013, 61(6), 436–445 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Comparative dating of Acacia: combining fossils and multiple phylogenies to infer ages of clades with poor fossil records Joseph T. MillerA,E, Daniel J. MurphyB, Simon Y. W. HoC, David J. CantrillB and David SeiglerD ACentre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO Box 1600 Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BRoyal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra, Vic. 3141, Australia. CSchool of Biological Sciences, Edgeworth David Building, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. DDepartment of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Table S1 Materials used in the study Taxon Dataset Genbank Acacia abbreviata Maslin 2 3 JF420287 JF420065 JF420395 KC421289 KC796176 JF420499 Acacia adoxa Pedley 2 3 JF420044 AF523076 AF195716 AF195684; AF195703 Acacia ampliceps Maslin 1 KC421930 EU439994 EU811845 Acacia anceps DC. 2 3 JF420244 JF420350 JF419919 JF420130 JF420456 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth 2 3 JF420259 JF420036 JF420366 JF419935 JF420146 KF048140 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth. 1 2 3 JF420293 JF420402 KC421323 JQ248740 JF420505 Acacia baeuerlenii Maiden & R.T.Baker 2 3 JF420229 JQ248866 JF420336 JF419909 JF420115 JF420448 Acacia beckleri Tindale 2 3 JF420260 JF420037 JF420367 JF419936 JF420147 JF420473 Acacia cochlearis (Labill.) H.L.Wendl. 2 3 KC283897 KC200719 JQ943314 AF523156 KC284140 KC957934 Acacia cognata Domin 2 3 JF420246 JF420022 JF420352 JF419921 JF420132 JF420458 Acacia cultriformis A.Cunn. ex G.Don 2 3 JF420278 JF420056 JF420387 KC421263 KC796172 JF420494 Acacia cupularis Domin 2 3 JF420247 JF420023 JF420353 JF419922 JF420133 JF420459 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 JF420269 JF420378 KC421251 KC955787 JF420485 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 KC283375 KC200761 JQ942686 KC421315 KC284195 Acacia deanei (R.T.Baker) M.B.Welch, Coombs 2 3 JF420294 JF420403 KC421329 KC955795 & McGlynn JF420506 Acacia dempsteri F.Muell. -

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

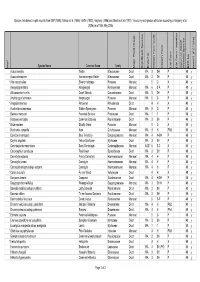

BFS048 Site Species List

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Pollination Ecology and Evolution of Epacrids

Pollination Ecology and Evolution of Epacrids by Karen A. Johnson BSc (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania February 2012 ii Declaration of originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Karen A. Johnson Statement of authority of access This thesis may be made available for copying. Copying of any part of this thesis is prohibited for two years from the date this statement was signed; after that time limited copying is permitted in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Karen A. Johnson iii iv Abstract Relationships between plants and their pollinators are thought to have played a major role in the morphological diversification of angiosperms. The epacrids (subfamily Styphelioideae) comprise more than 550 species of woody plants ranging from small prostrate shrubs to temperate rainforest emergents. Their range extends from SE Asia through Oceania to Tierra del Fuego with their highest diversity in Australia. The overall aim of the thesis is to determine the relationships between epacrid floral features and potential pollinators, and assess the evolutionary status of any pollination syndromes. The main hypotheses were that flower characteristics relate to pollinators in predictable ways; and that there is convergent evolution in the development of pollination syndromes. -

American River, Kangaroo Island

TECHNICAL REPORTS & GUIDELINES TECHNICAL REPORTS & GUIDELINES DEVELOPMENT REPORT Appendices A to I & K to L Issued September 2016 CONTENTS A. Infrastructure & Services Report (BCA Engineers) B. Native V egetation Assessment (Botanical Enigmerase) C. Landscape Concept Plan (Botanical Enigmerase) D. Fauna Assessment (Envisage Environmental) E. Archeological and Heritage Assessment (K. Walshe) N.B. This report is to be updated - it contains incorrect information regarding location of Plaque & Anchor F. Design Review 1 Letter (ODASA) G. Noise Assessment (Sonos) H. Stormwater Management (fmg Engineers) I. DR Guidelines (Development Assessment Commission) K. Draft CEMMP & OEMMP (PARTI) L. Traffic Impact Assessment ( infraPlan) - - - - - NATIVE VEGETATION CLEARANCE ASSESSMENT AND LANDSCAPE PLAN PROPOSED KANGAROO ISLAND RESORT AMERICAN RIVER CITY AND CENTRAL DEVELOPMENT (CCD) HOTEL AND RESORTS LLC 31 AUGUST 2016 BOTANICAL ENIGMERASE Michelle Haby- 0407 619 229 PO Box 639 Daniel Rowley- 0467 319 925 Kingscote SA 5223 ABN- 59 766 096 918 [email protected] NATIVE VEGETATION CLEARANCE ASSESSMENT AND LANDSCAPE PLAN 31 August 2016 Citation: Haby, M and Rowley, D.J. (2016) Native Vegetation Assessment and Landscape Plan- Proposed American River Resort. Internal report to City and Central Development (CCD) Hotel and Resorts LLC. This report was researched and prepared by Botanical Enigmerase Email: [email protected] in accordance with the agreement between, on behalf of and for the exclusive use of City and Central Development (CCD) Hotel and Resorts LLC 2800 156th Avenue SE Suite 130 Bellevue, WA 98007 [email protected] Michelle Haby is a Native Vegetation Council accredited consultant, accredited to prepare data reports for clearance consent under Section 28 of the Native Vegetation Act 1991 and applications made under one of the Native Vegetation Regulations 2003. -

Honey and Pollen Flora of SE Australia Species

List of families - genus/species Page Acanthaceae ........................................................................................................................................................................34 Avicennia marina grey mangrove 34 Aizoaceae ............................................................................................................................................................................... 35 Mesembryanthemum crystallinum ice plant 35 Alliaceae ................................................................................................................................................................................... 36 Allium cepa onions 36 Amaranthaceae ..................................................................................................................................................................37 Ptilotus species foxtails 37 Anacardiaceae ................................................................................................................................................................... 38 Schinus molle var areira pepper tree 38 Schinus terebinthifolius Brazilian pepper tree 39 Apiaceae .................................................................................................................................................................................. 40 Daucus carota carrot 40 Foeniculum vulgare fennel 41 Araliaceae ................................................................................................................................................................................42 -

Poaceae: Pooideae) Based on Plastid and Nuclear DNA Sequences

d i v e r s i t y , p h y l o g e n y , a n d e v o l u t i o n i n t h e monocotyledons e d i t e d b y s e b e r g , p e t e r s e n , b a r f o d & d a v i s a a r h u s u n i v e r s i t y p r e s s , d e n m a r k , 2 0 1 0 Phylogenetics of Stipeae (Poaceae: Pooideae) Based on Plastid and Nuclear DNA Sequences Konstantin Romaschenko,1 Paul M. Peterson,2 Robert J. Soreng,2 Núria Garcia-Jacas,3 and Alfonso Susanna3 1M. G. Kholodny Institute of Botany, Tereshchenkovska 2, 01601 Kiev, Ukraine 2Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany MRC-166, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, District of Columbia 20013-7012 USA. 3Laboratory of Molecular Systematics, Botanic Institute of Barcelona (CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s.n., E08038 Barcelona, Spain Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Abstract—The Stipeae tribe is a group of 400−600 grass species of worldwide distribution that are currently placed in 21 genera. The ‘needlegrasses’ are char- acterized by having single-flowered spikelets and stout, terminally-awned lem- mas. We conducted a molecular phylogenetic study of the Stipeae (including all genera except Anemanthele) using a total of 94 species (nine species were used as outgroups) based on five plastid DNA regions (trnK-5’matK, matK, trnHGUG-psbA, trnL5’-trnF, and ndhF) and a single nuclear DNA region (ITS). -

Flora Survey on Hiltaba Station and Gawler Ranges National Park

Flora Survey on Hiltaba Station and Gawler Ranges National Park Hiltaba Pastoral Lease and Gawler Ranges National Park, South Australia Survey conducted: 12 to 22 Nov 2012 Report submitted: 22 May 2013 P.J. Lang, J. Kellermann, G.H. Bell & H.B. Cross with contributions from C.J. Brodie, H.P. Vonow & M. Waycott SA Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Vascular plants, macrofungi, lichens, and bryophytes Bush Blitz – Flora Survey on Hiltaba Station and Gawler Ranges NP, November 2012 Report submitted to Bush Blitz, Australian Biological Resources Study: 22 May 2013. Published online on http://data.environment.sa.gov.au/: 25 Nov. 2016. ISBN 978-1-922027-49-8 (pdf) © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resouces, South Australia, 2013. With the exception of the Piping Shrike emblem, images, and other material or devices protected by a trademark and subject to review by the Government of South Australia at all times, this report is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. All other rights are reserved. This report should be cited as: Lang, P.J.1, Kellermann, J.1, 2, Bell, G.H.1 & Cross, H.B.1, 2, 3 (2013). Flora survey on Hiltaba Station and Gawler Ranges National Park: vascular plants, macrofungi, lichens, and bryophytes. Report for Bush Blitz, Australian Biological Resources Study, Canberra. (Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia: Adelaide). Authors’ addresses: 1State Herbarium of South Australia, Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (DEWNR), GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia. -

Potential Agroforestry Species and Regional Industries for Lower Rainfall

PotentialPotential agroforestryagroforestry speciesspecies andand regionalregional industriesindustries forfor lowerlower rainfall rainfall southernsouthern AustraliaAustralia FLORASEARCHFLORASEARCH 2 2 Australia Australia Potential agroforestry species and regional industries for lower rainfall southern Australia FLORASEARCH 2 Australia A report for the RIRDC / L&WA / FWPA / MDBC Joint Venture Agroforestry Program Future Farm Industries CRC by Trevor J. Hobbs, Mike Bennell, Dan Huxtable, John Bartle, Craig Neumann, Nic George, Wayne O’Sullivan and David McKenna January 2009 © 20092008 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 1 74151 479 7 ISSN 1440-6845 Please cite this report as: Hobbs TJ, Bennell M, Huxtable D, Bartle J, Neumann C, George N, O’Sullivan W and McKenna D (2008). Potential agroforestry species and regional industries for lower rainfall southern Australia: FloraSearch 2. Report to the Joint Venture Agroforestry Program (JVAP) and the Future Farm Industries CRC*. Published by RIRDC, Canberra Publication No. 07/082 Project No. UWA-83A The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia -

Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 4 2011 Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B. Harper Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Sula Vanderplank Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Mark Dodero Recon Environmental Inc., San Diego, California Sergio Mata Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Jorge Ochoa Long Beach City College, Long Beach, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Alan B.; Vanderplank, Sula; Dodero, Mark; Mata, Sergio; and Ochoa, Jorge (2011) "Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol29/iss1/4 Aliso, 29(1), pp. 25–42 ’ 2011, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden PLANTS OF THE COLONET REGION, BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO, AND A VEGETATION MAPOF COLONET MESA ALAN B. HARPER,1 SULA VANDERPLANK,2 MARK DODERO,3 SERGIO MATA,1 AND JORGE OCHOA4 1Terra Peninsular, A.C., PMB 189003, Suite 88, Coronado, California 92178, USA ([email protected]); 2Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711, USA; 3Recon Environmental Inc., 1927 Fifth Avenue, San Diego, California 92101, USA; 4Long Beach City College, 1305 East Pacific Coast Highway, Long Beach, California 90806, USA ABSTRACT The Colonet region is located at the southern end of the California Floristic Province, in an area known to have the highest plant diversity in Baja California. -

Recovery Plan for Nationally Threatened Plant Species on Kangaroo Island South Australia

Recovery plan for nationally threatened plant species on Kangaroo Island South Australia Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board Australian Government Title: Recovery plan for nationally threatened plant species on Kangaroo Island South Australia © Department of Environment, Water & Natural Resources This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgement of the sources but no commercial usage or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources PO Box 1047 Adelaide SA 5001 Citation Taylor, D.A. (2012). Recovery plan for nationally threatened plant species on Kangaroo Island South Australia. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia. Cover Photos: The nationally threatened species Leionema equestre on the Hog Bay Road, eastern Kangaroo Island (Photo D. Taylor) Acknowledgements This Plan was developed with the guidance, support and input of the Kangaroo Island Threatened Plant Steering Committee and the Kangaroo Island Threatened Plant Recovery Team. Members included Kylie Moritz, Graeme Moss, Vicki-Jo Russell, Tim Reynolds, Yvonne Steed, Peter Copley, Annie Bond, Mary-Anne Healy, Bill Haddrill, Wendy Stubbs, Robyn Molsher, Tim Jury, Phil Pisanu, Doug Bickerton, Phil Ainsley and Angela Duffy. Valuable advice regarding the ecology, identification and location of threatened plant populations was received from Ida and Garth Jackson, Bev and Dean Overton and Rick Davies. The support of the Kangaroo Island staff of the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources was also greatly appreciated. Funding for the preparation of this plan was provided by the Australian Government, Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board and the Threatened Species Network (World Wide Fund for Nature).