Threatened and Declining Birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Intense Nest Predation in the Decline of Scarlet Robins and Eastern Yellow Robins in Remnant Woodland Near Armidale, New South Wales

The role of intense nest predation in the decline of Scarlet Robins and Eastern Yellow Robins in remnant woodland near Armidale, New South Wales S. J. S. DEBDSI A study of open-nesting Eastern Yellow Robins Eopsaltria australis and Scarlet Robins Petroica multicolor, on the New England Tablelands of New South Wales in 2000-02, found Iow breeding success typical of eucalypt woodland birds. The role of intense nest predation in the loss of birds from woodland fragments was investigated by means of predator-exclusion cages at robin nests, culling of Pied Currawongs Strepera graculina, and monitoring of fledging and recruitment in the robins. Nest-cages significantly improved nest success (86% vs 20%) and fledging rate (1.6 vs 0.3 fledglings per attempt) for both robin species combined (n = 7 caged, 20 uncaged). For both robin species combined, culling of currawongs produced a twofold difference in nest success (33% vs 14%), a higher fledging rate (0.5 vs 0.3 per attempt), and a five-day difference in mean nest survival (18 vs 13 days) (n = 62 nests), although sample sizes for nests in the cull treatment (n = 18) were small and nest predation continued. Although the robin breeding population had not increased one year after the cull, the pool of Yellow Robin recruits in 2001-03, after enhanced fledging success, produced two emigrants to a patch where Yellow Robins had become extinct. Management to assist the conservation of open-nesting woodland birds should address control of currawongs. Key words: Woodland birds, Habitat fragmentation, Nest predation, Predator exclusion, Predator removal. -

Whistler3 Frontcover

The Whistler is the occasionally issued journal of the Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. ISSN 1835-7385 The aims of the Hunter Bird Observers Club (HBOC), which is affiliated with Bird Observation and Conservation Australia, are: To encourage and further the study and conservation of Australian birds and their habitat To encourage bird observing as a leisure-time activity HBOC is administered by a Committee: Executive: Committee Members: President: Paul Baird Craig Anderson Vice-President: Grant Brosie Liz Crawford Secretary: Tom Clarke Ann Lindsey Treasurer: Rowley Smith Robert McDonald Ian Martin Mick Roderick Publication of The Whistler is supported by a Sub-committee: Mike Newman (Joint Editor) Harold Tarrant (Joint Editor) Liz Crawford (Production Manager) Chris Herbert (Cover design) Liz Huxtable Ann Lindsey Jenny Powers Mick Roderick Alan Stuart Authors wishing to submit manuscripts for consideration for publication should consult Instructions for Authors on page 61 and submit to the Editors: Mike Newman [email protected] and/or Harold Tarrant [email protected] Authors wishing to contribute articles of general bird and birdwatching news to the club newsletter, which has 6 issues per year, should submit to the Newsletter Editor: Liz Crawford [email protected] © Hunter Bird Observers Club Inc. PO Box 24 New Lambton NSW 2305 Website: www.hboc.org.au Front cover: Australian Painted Snipe Rostratula australis – Photo: Ann Lindsey Back cover: Pacific Golden Plover Pluvialis fulva - Photo: Chris Herbert The Whistler is proudly supported by the Hunter-Central Rivers Catchment Management Authority Editorial The Whistler 3 (2009): i-ii The Whistler – Editorial The Editors are pleased to provide our members hopefully make good reading now, but will and other ornithological enthusiasts with the third certainly provide a useful point of reference for issue of the club’s emerging journal. -

The Rainbow Bird

The Rainbow Bird Volume 5 Number 3 August 2016 (Issue 87) MALLEE, MARLEE OR MAWLEY It might be interesting to club members to know that the word "mallee" is derived from the aboriginal word for the Eucalyptus Dumosa, perhaps the main species of mallee in this area. I guess that the aboriginals also used the term to cover all the various species now known by that name. European surveyors originally spelt the word in various ways. "Mallee", "Mar-lie" and then "Marlee" were variants. Later still the spelling "Mallay" was also used and in 1849 the spelling "Mawley" was sometimes used. However, in the late 1870’s South Australian wheat growers moved in to settle the mallee country, between SA Murray and southern Victorian Mallee area, and the present spelling of the word became standardised. I gleaned this information from an old book of my father’s on the Murray Valley that was written by J MacDonald Holmes and published by Angus and Robertson in 1948. Allan Taylor Contents 1. Mallee, Marlee or Mawley 2. Yarrara & Mallanbool Flora & Fauna Reserves outing 3. Nurnurnemal Nature Conservation Reserve & Castles Crossing outing 4. Ned’s Corner outing and survey 5. Is this plover mystery solved? 6. Katarapko National Park 7. Waikerie Bird Watchers Trail 8. Endangered Aussie bird bouncing back 9. A yellow Blue Bonnet 10. Club calendar 11. Farewell 12. Interesting sightings 13. Lindsay Cupper's photos Eucalyptus Dumosa The Rainbow Bird YARRARA & MALLANBOOL FLORA & FAUNA RESERVES OUTING – MAY 7TH, 2016 The clouds threatened with rain and the sun shone half- heartedly as a group of birders met at the Bike Hub. -

The Records of the Speckled Warbler from South Australia S

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST, 28 102 THE RECORDS OF THE SPECKLED WARBLER FROM SOUTH AUSTRALIA S. A. PARKER Accepted January 1979 The South Australian records of the Speckled from South Australia is that referred to by Warbler Sericornis (Chthonicola) sagittatus Cleland et al. in Cain (1937), of nine specimens are problematic. The latest commentator, H. T. from Tarpeena, 24 km north of Mount Condon (1969:112), wrote: 'lot is claimed that Gambier, collected by Andrews in 1868. These a number of specimens were taken at Tarpeena, specimens cannot be traced in the South north of Mt Gambier, in October, 1868. Australian Museum, and it is likely that Cleland Others were supposed to have been collected et al. based their remark on a ms. list of in the vicinity of Lake Eyre (1875), [and] Andrews, now also lost. The next record is of Coralbignie (Gawler Ranges, July/August, a specimen taken by Andrews on the 1874-75 1883). The claimed occurrence of the species Lewis Expedition to the Lake Eyre district in this State is doubtful.'.lp the present note I (Waterhouse 1875); this too is now missing. suggest that the-five South Australian records, The third record is of two specimens from three of which were based on specimens Coralbignie, Gawler Ranges, collected by collected by F. W. Andrews, are in fact Andrews between July 26 and August 20, 1883 referable to the superficially similar Cala (Cleland et al. op. cit.). There is a Speckled manthus Sericornis fuliginosus. Warbler specimen in the SAM bearing these The first record of the Speckled Warbler data - B7690, registered and labelled by 103 MARCH,1980 John Sutton on January 25, 1927. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia Hugh Possingham and Mat Gilfedder – January 2011 [email protected] www.ecology.uq.edu.au 3379 9388 (h) Other photos, records and comments contributed by: Cathy Gilfedder, Mike Bennett, David Niland, Mark Roberts, Pete Kyne, Conrad Hoskin, Chris Sanderson, Angela Wardell-Johnson, Denis Mollison. This guide provides information about the birds, and how to bird on, Oxley Creek Common. This is a public park (access restricted to the yellow parts of the map, page 6). Over 185 species have been recorded on Oxley Creek Common in the last 83 years, making it one of the best birding spots in Brisbane. This guide is complimented by a full annotated list of the species seen in, or from, the Common. How to get there Oxley Creek Common is in the suburb of Rocklea and is well signposted from Sherwood Road. If approaching from the east (Ipswich Road side), pass the Rocklea Markets and turn left before the bridge crossing Oxley Creek. If approaching from the west (Sherwood side) turn right about 100 m after the bridge over Oxley Creek. The gate is always open. Amenities The main development at Oxley Creek Common is the Red Shed, which is beside the car park (plenty of space). The Red Shed has toilets (composting), water, covered seating, and BBQ facilities. The toilets close about 8pm and open very early. The paths are flat, wide and easy to walk or cycle. When to arrive The diversity of waterbirds is a feature of the Common and these can be good at any time of the day. -

Breeding Record of the Black Honeyeater at Port Neill, Eyre Peninsula

76 SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST, 30 BREEDING RECORD OF THE BLACK HONEYEATER AT PORT NEILL, EYRE PENINSULA TREVOR COX Eckert et al. (1985) pointed out that the Black indicated by dead branches protruding slightly Honeyeater Certhionyx niger has been reported above the vegetation. The male would perch on from Eyre Peninsula but that its occurrence there each branch in turn for approximately one minute requires substantiation. In this note, I report the and repeatedly give a single note call. Display occurrence and breeding ofBlack Honeyeaters on flights at this time attained a height of 1O-12m and the Peninsula. the female was only heard occasionally, uttering a On 5 October 1985, I saw, six to ten Black soft, single note call from the nest area. The male Honeyeaters in a small patch of scrub on a rise defended the territory against other Black adjacent to the southern edge of the township of Honeyeaters, a Singing Honeyeater Port Neill on Eyre Peninsula. The scrub consisted Lichenostomus virescens and a Tawny-crowned of stunted maIlee, Broomebush Melaleuca Honeyeater Gliciphila melanops. It chased the uncinata, Porcupine Grass Triodia irritans and latter 50m on one occasion. shrubs. The only eucalypt flowering at the time The nest wasin a stunted mallee at 0.35m height. was Red Mallee Eucalyptus socialis. It was a small cup 55mm in diameter and 40mm A description taken from my field notes of the deep, made of fine sticks bound with spider web, birds seen at Port Neill is as follows: lined with hair roots and adorned with pieces of A small honeyeater of similar size to silvereye [Zosterops], barkhanging from it. -

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island

A Guide to the Birds of Barrow Island Operated by Chevron Australia This document has been printed by a Sustainable Green Printer on stock that is certified carbon in joint venture with neutral and is Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) mix certified, ensuring fibres are sourced from certified and well managed forests. The stock 55% recycled (30% pre consumer, 25% post- Cert no. L2/0011.2010 consumer) and has an ISO 14001 Environmental Certification. ISBN 978-0-9871120-1-9 Gorgon Project Osaka Gas | Tokyo Gas | Chubu Electric Power Chevron’s Policy on Working in Sensitive Areas Protecting the safety and health of people and the environment is a Chevron core value. About the Authors Therefore, we: • Strive to design our facilities and conduct our operations to avoid adverse impacts to human health and to operate in an environmentally sound, reliable and Dr Dorian Moro efficient manner. • Conduct our operations responsibly in all areas, including environments with sensitive Dorian Moro works for Chevron Australia as the Terrestrial Ecologist biological characteristics. in the Australasia Strategic Business Unit. His Bachelor of Science Chevron strives to avoid or reduce significant risks and impacts our projects and (Hons) studies at La Trobe University (Victoria), focused on small operations may pose to sensitive species, habitats and ecosystems. This means that we: mammal communities in coastal areas of Victoria. His PhD (University • Integrate biodiversity into our business decision-making and management through our of Western Australia) -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

Berriquin LWMP Wildlife

Berriquin Wildlife Murray Land & Water Management Plan Wildlife Survey 2005-2006 Matthew Herring David Webb Michael Pisasale INTRODUCTION Why do a wildlife survey? 106 farms and were surveyed One of the great things about between June 2005 and March living in rural Australia is all the 2006. They incorporated a range wildlife that we share the land- of vegetation types (e.g. Black scape with. Historically, humans Box Woodland) as well as reveg- have impacted on the survival of etation on previously cleared many native plants and animals. land and constructed wetlands. Fortunately, there is a grow- Methods used to survey wildlife ing commitment in the country included: to wildlife conservation on the farm. As we improve our knowl- - Bird surveys edge and understanding of the - Log rolling for reptiles and local landscape and the animals frogs and plants that live in it we will - Spotlighting for mammals, rep be in a much better position to tiles and nocturnal birds conserve and enhance our natu- - Elliot traps for small mammals ral heritage for future genera- and reptiles tions. - Pitfall trapping for reptiles and frogs This wildlife survey was an ini- - Harp traps for bats tiative of the Berriquin Land & - Using the “Anabat” to record Water Management Plan (LWMP) bat calls M.Herring Working Group and is the largest - Call broadcasting to attract Wildlife expert Adam Bester and most extensive ever un- birds with 11 Little Forest Bats, one dertaken in the area. Berriquin of Berriquin’s most abundant was one of four LWMP areas that Other targeted methods were mammals. -

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

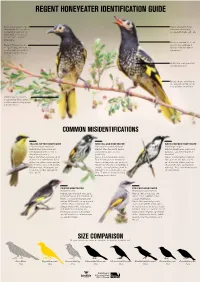

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden.