East West Link

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Projects

BORAL ASPHALT Build something great™ CASE STUDY Major Projects PENINSULA LINK 2018 EDITION CASE STUDY Major Projects PENINSULA LINK 2018 EDITION Client/Construction Team Client: Abigroup. Contractor: Boral Resources (Vic). Existing Conditions Wet weather can cause costly delays in asphalt works. After experiencing two of the wettest years on record in Australia, a compressed program was implemented which saw approximately 300,000 tonnes of asphalt pavement laid in four months, with our largest Project Impact Statement With construction now completed and the month at 113,000 tonnes. freeway opened, Lend Lease Infrastructure Originally drafted in the 1969 Melbourne Design Services now operates and will maintain Transportation Plan, Peninsula Link is a six-lane To ensure greater comfort and safety for road the freeway for the next 25 years before freeway spanning 27 kilometres, beginning at users, a key factor in the performance of the handing back the asset in an agreed the southern end of Eastlink in Carrum Downs freeway is ride quality, which is a measure of condition to VicRoads. and leading into the Mornington Peninsula the ‘roughness’ of the road surface. After Freeway in Mount Martha. Project Scope construction was completed, a series of measurements showed that the ride comfort Peninsula Link gives drivers the choice of The scope of the works included: along the 27 kilometre span came well within bypassing nine sets of traffic lights and six VicRoads specifications. major roundabouts, allowing road users to • Full depth asphalt in five layers travel from the Mornington Peninsula to including OGA surfacing for the Performance northern 14km Melbourne Airport without encountering a Of the 410,000 tonnes of asphalt produced, single traffic light. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 for Personal Use Only Use Personal For

For personal use only CONNECTEAST ANNU A L REPO R ANNUAL REPORT 2011 T 2011 For personal use only 2 Hillcrest Avenue Ringwood VIC 3134 Australia PO Box 804 Ringwood VIC 3134 T 03 9955 1700 F 03 9955 1701 ConnectEast.com.au EastLink.com.au EASTLINK CORPORATE DEVELOPMENT CORRIDOR DIRECTORY BOARD OF DIRECTORS REGISTERED AND PRINCIPAL COMPLAINTS HANDLING ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE ConnectEast has in place a formal Chairman EastLink Operations Centre complaints handling procedure, which AN UPdate ON DEVELOPMENTS WITHIN Anthony Shepherd 2 Hillcrest Avenue is available on our website at THE EASTLINK CORRIDOR Ringwood VIC 3134 ConnectEast.com.au. Directors Tel (03) 9955 1700 The responsible entity is a member Connecting to EastLink at its southern Fax (03) 9955 1701 end, the new 27km Peninsula Link is Dennis Cliche (Managing Director) of the Financial Ombudsman Service. taking shape from Carrum Downs to Bruce Beeren Unitholders unable to resolve a dispute † RESPONSIBLE ENTITY Mt Martha. Design and construction John Collier with ConnectEast may contact the Financial Paul Dougas Ombudsman Service on 1300 78 08 08 or company Abigroup has now commenced ConnectEast Management Limited Jim Hall visit its website at fos.org.au. construction of the project’s 45 structures. Yvonne von Hartel AM 2 Hillcrest Avenue Construction of the seamless interchange Ringwood VIC 3134 PRIVACY between EastLink and Peninsula Link is COMPANY SecretarY Tel (03) 9955 1700 already underway. The first beams have ConnectEast honours without reservation Fax (03) 9955 1701 been placed on the Peninsula Link bridge Tony Hudson our obligation to respect and protect over EastLink, and soil has been excavated the privacy of the personal information SECURITIES REGISTRAR underneath existing bridges to allow for EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT of individuals with whom we deal. -

Annual Report 2012-2013

Annual Report 2012-2013 LINKING MELBOURNE AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT 2012-13 1 Published by Linking Melbourne Authority Building 1 Level 1 Brandon Business Park 540 Springvale Road Glen Waverley Victoria 3150 September 2013 Also published on www.linkingmelbourne.vic.gov.au © State of Victoria 2013 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with provisions of the Copyright Act. Authorised by the Victorian Government 121 Exhibition Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Printed on Australian made, carbon neutral, recycled paper using waterless printing. Contents Chairman’s report . 4 Around the world, CEO’s report . 5 there are few other Delivering for Melbourne . 6 organisations with LMA’s depth Our purpose and priorities . 6 of expertise Government priorities . 6 and experience Governance . 8 in planning, Our Board . 9 designing and Our people . 9 delivering large- Peninsula Link . 10 scale road Peninsula Link opens . 10 transport projects. Getting to opening day . 10 Environment . 12 Social benefits . 12 Engaging the community . 14 Availability Public Private Partnership . 15 East West Link . 16 Project benefits . 16 Planning for the East West Link . 18 Kick starting the market process . 20 Keeping communities informed . 21 EastLink service centres . 22 Supporting our people . 23 Abbreviations . 24 Financial statements . 25 Statutory information . 70 Disclosure index . 73 Chairman’s report Linking Melbourne Authority’s (LMA) achievements and record continue to demonstrate the advantages of using a specialist, multi-disciplinary body to oversee the delivery of PPP road projects. Around the world, there are few other placing most of the road in tunnel translates organisations with LMA’s depth of expertise into major improvements in the surface and experience in planning, designing and environment, including improvements to delivering large-scale road transport projects. -

Submission Cover Sheet Crib Point Inquiry and Advisory Committee EES 3104

Submission Cover Sheet Crib Point Inquiry and Advisory Committee EES 3104 Request to be heard?: No Full Name: Steph Miller Organisation: Address of affected property: Attachment 1: Attachment 2: Attachment 3: Submission: My name is Steph Miller and I care about the environment in Westernport Bay. Westernport bay is an area of considerable biodiversity and is listed on the Australia heritage registrar. We are rapidly destroying nature and cannot continue like this. Embrace renewable energy and give your kids a future. I thank the Crib Point Inquiry and Advisory Committee and the Minister for Planning for the opportunity to make a submission to the environment assessment of the Crib Point gas import jetty and gas pipeline project. There are a variety of issues which should deem this proposal unacceptable under its current form and that I will point to in my submission but the issue that concerns me most is the impact on our internationally recognised wetlands and wildlife. A new fossil fuel project like the gas import terminal which AGL is proposing would introduce new risks to the local community and visitors to the area. These risks include exposing people to toxic hydrocarbons which may leak from the facility and increased risk of accidental fire and explosion as noted in EES Technical Report K. The nearest homes to the import facility are about 1.5 kms away and Wooleys Beach is also close to the site. AGL have completed only preliminary quantitative risk assessments on these risks and have deemed the risk acceptable on that basis. It is not acceptable to present preliminary studies and the EES should not continue until we have an independent expert to provide final risk assessments. -

Managing Traffic Impacts

JANUARY 2020 Traffic on Wells Road MORDIALLOC FREEWAY Managing traffic and transport impacts We’re building the Mordialloc The project will take 13,000 trucks These plans will consider existing Freeway to connect the off local roads, giving local roads back road conditions to decide the best to local residents. way to manage temporary changes Mornington Peninsula Freeway to traffic flow. to the Dingley Bypass. Keeping you moving To reduce the impacts we'll schedule We’ll prepare Traffic Management Plans The Mordialloc Freeway will slash works impacting traffic outside of peak to maintain the safety of the public and travel times and ease congestion times. While we're building the new our workers and reduce the impact to in Melbourne’s south east, providing Freeway we'll also regularly monitor traffic during construction. a safer, more reliable journey. traffic conditions in the area. roadprojects.vic.gov.au Authorised by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne 5 Wellington Rd Monash Fwy 2 3 Princes Hwy Dingley Byp Clayton Rd Westall Rd Warrigal Rd Lightwood Rd Stud Rd 1 Springvale Rd Heatherton Rd Junction Rd Eastlink Centre Rd Old Dandenong Rd Heatherton Rd Lower Dandenong Rd Beach Rd Woodlands Dr Corrigan Rd M Mills Rd Power Rd o r d i a l l i o Dandenong Byp c Princes Hwy F w y Boundary Road Wells Rd Abbotts Rd Hammond Rd S. Gippsland Hwy Eastlink 1 Truck route from Heatherton Managing truck Using traffic management movements We'll use traffic management Western Port Hwy 4 2 Truck route from Lysterfield Thompson Rd measures to keep you and workers There will be a large number of safe during works. -

Peninsula Link

PENINSULA LINK PROJECT NAME/LOCATION PROJECT DETAILS Peninsula Link, south of Melbourne on Overview the Mornington Peninsula, Victoria Peninsula Link, the 27-kilometre road link between the EastLink Freeway at Carrum Downs and the Mornington Peninsula Freeway at Mount Martha in Victoria was constructed between March 2011 and January 2013 by OWNER/PRINCIPAL Linking Melbourne Authority on behalf infrastructure giant Abigroup (now Lend Lease Group). of the State of Victoria The $759 million project brought many benefits to people living, working and visiting Frankston and the Mornington Peninsula. Peninsula Link has saved MAIN CONTRACTOR people time with a full trip between Mt Martha and Carrum Downs taking just Abigroup (now Lend Lease Group) 17 minutes – a saving of up to 40 minutes in peak traffic. Alex Fraser contributions MATERIALS SUPPLIED In March 2011, Alex Fraser successfully tendered for the supply of Class 3 Class 3 Crushed Concrete and 4 Recycled Concrete and the first truck loads arrived in November 2011. Class 4 Crushed Concrete Peninsula Link was completed in January 2013 and Alex Fraser played a significant role, supplying approximately 300,000 tonnes of recycled road SPECIFICATIONS base. The following aspects played a large role in awarding the tender: VicRoads section 820 VicRoads section 821 Location: most materials for this project were supplied from Alex Fraser’s Clarinda production facility. Its close proximity to the TOTAL TONNAGES SUPPLIED construction site allowed for competitive freight costs Approximately 300,000 tonnes Capability: Alex Fraser sites had the well-proven capacity to produce and supply with the large volumes of recycled concrete required for the project TONNES SAVED Quality products: Alex Fraser had supplied high-quality tested and Approximately 26,000 tonnes specified Class 3 and 4 road base and aggregates to other projects of similar size ALEX FRASER CONTACT Logistics: Alex Fraser had a proven capability to schedule and deliver Mark Barraclough the required 3,000 tonnes per day. -

Media Release Eastlink.Com.Au

Media Release EastLink.com.au 14 November 2016 – For Immediate Release EASTLINK ASSESSED TO BE A GLOBAL LEADER IN INFRASTRUCTURE SUSTAINABILITY The inaugural 2016 GRESB Infrastructure Assessment has ranked Melbourne’s EastLink 1st for sustainability among transportation assets from across the globe. The 2016 GRESB Infrastructure Assessment covers the environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance of 134 infrastructure assets and 51 infrastructure funds across 53 countries and six continents. Following the release of the 2016 GRESB Infrastructure Assessment results, EastLink’s Managing Director Charles Griplas was delighted that EastLink’s sustainability performance has been recognised internationally. “To be ranked number 1 by GRESB for transportation asset sustainability demonstrates that EastLink is a world-leading infrastructure asset right here in Melbourne,” said Mr Griplas. “It is notable that GRESB has also ranked EastLink 1st among toll road operations, 1st among assets in the Oceania region, and 2nd among all types of infrastructure assets across the globe.” “With its modern design, 24/7 traffic control room, intelligent transport systems, incident response teams and traffic control vehicles, all operated by a highly motivated and customer-focused team, EastLink is the safest freeway in Melbourne, offering the highest quality of service and reliability to motorists,” said Mr Griplas. “EastLink’s environmental sustainability is unique for a road, including 480 hectares of landscaping, 4 million native trees, shrubs and plants, and more than 60 wetlands that treat rainwater running off the road surface. This ensures that the water is returned to a relatively high quality before entering local creeks,” said Mr Griplas. “In an Australian first, EastLink is now upgrading its 10 tunnel exhaust fans to incorporate variable speed drives, which will result in considerable direct energy savings and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 6,441t CO2-e per annum. -

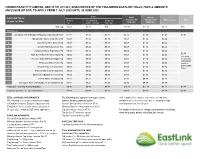

Eastlink Tolls, Fees & Amounts (Inclusive of Gst) to Apply from 1 July 2020 Until 30 June 2021

CONNECTEAST PTY LIMITED, ABN 99 101 213 263, GIVES NOTICE OF THE FOLLOWING EASTLINK TOLLS, FEES & AMOUNTS (INCLUSIVE OF GST) TO APPLY FROM 1 JULY 2020 UNTIL 30 JUNE 2021. Cars EASTLINK TOLLS Light Heavy Commercial Commercial Motorcycles Taxis Charge Toll Rates Normal Weekends & Single toll trip public holidays zone trip Vehicles Vehicles Toll cap $6.48 $5.18 N/A $10.36 $17.16 $3.23 N/A Toll zones: 1 Springvale Rd to Ringwood Bypass & Maroondah Hwy $2.97 $2.38 $2.97 $4.76 $7.89 $1.49 $2.97 2 Maroondah Hwy to Canterbury Rd $0.43 $0.34 $0.34 $0.69 $1.14 $0.22 3 Canterbury Rd to Boronia Rd $0.43 $0.34 $0.34 $0.69 $1.14 $0.22 4 Boronia Rd to Burwood Hwy $0.43 $0.34 $0.34 $0.69 $1.14 $0.22 5 Burwood Hwy to High Street Rd $0.43 $0.34 $0.34 $0.69 $1.14 $0.22 $2.79 6 High Street Rd to Ferntree Gully Rd $0.65 $0.52 $0.52 $1.03 $1.72 $0.32 (for a trip 7 Ferntree Gully Rd to Wellington Rd $0.65 $0.52 $0.52 $1.03 $1.72 $0.32 on any part of EastLink 8 Wellington Rd to Police Rd $0.65 $0.52 $0.52 $1.03 $1.72 $0.32 south of Maroondah 9 Monash Fwy to Princes Hwy $0.65 $0.52 $0.52 $1.03 $1.72 $0.32 Hwy) 10 Princes Hwy to Cheltenham Rd $0.65 $0.52 $0.52 $1.03 $1.72 $0.32 11 Dandenong Bypass to Greens Rd $0.65 $0.52 $0.52 $1.03 $1.72 $0.32 12 Greens Rd to Thompson Rd $1.51 $1.21 $1.21 $2.42 $4.00 $0.76 13 Thompson Rd to Peninsula Link & Frankston Fwy $1.51 $1.21 $1.21 $2.42 $4.00 $0.76 Trip pass – per trip in one direction $6.48 $6.48 $6.48 $10.36 $17.16 $3.23 $6.48 Trip pass purchase fee (per transaction) $3.08 $3.08 $3.08 $3.08 $3.08 $3.08 $3.08 FEES, CHARGES AND AMOUNTS The following also apply to non-tag accounts GST is applied to a complete trip, not to each toll zone, The following fees, charges and amounts apply with the flexible payment option: and minor differences may occur due to rounding for trips to EastLink accounts, EastLink trip passes and Account Set Up Amount minimum $7.30 involving more than one toll zone. -

Management of Major Road Projects

Management of Major Road Projects Management of Major Road Projects June 2011 Victorian Auditor-General’s Report June 2011 2010-11:34 2010-11:34 Level 24 Telephone 61 3 8601 7000 35 Collins Street Facsimile 61 3 8601 7010 Melbourne Vic. 3000 www.audit.vic.gov.au V I C T O R I A Victorian Auditor-General Management of Major Road Projects Ordered to be printed VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER June 2011 PP No 38, Session 2010–11 This report has been produced to ISO14001 environmental standards. It is printed on FSC credited Novatech Satin paper. The print supplier, Blue Star PRINT has initiated an EMS promoting minimisation of environmental impact through the d eployment of efficient technology, rigorous quality management procedures and a philosophy of reduce, re-use and recycle. ISBN 978 1 921650 78 9 The Hon. Bruce Atkinson MLC The Hon. Ken Smith MP President Speaker Legislative Council Legislative Assembly Parliament House Parliament House Melbourne Melbourne Dear Presiding Officers Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my performance report on the Management of Major Road Projects. Yours faithfully D D R PEARSON Auditor-General 1 June 2011 Victorian Auditor-General’s Report Management of Major Road Projects iii Contents Audit summary............................................................................................vii Background.............................................................................................................vii Conclusions .......................................................................................................... -

Peninsula Link Project

Attachment 7 Peninsula Link Project Incorporated Document, February 2014 Mornington Peninsula Planning Scheme Incorporated document pursuant to section 6(2)(j) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 (Amends earlier version of July 2009) Attachment 7 2 1.0 INTRODUCTION This document is an incorporated document in the Mornington Peninsula Planning Scheme pursuant to section 6(2)(j) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. The land identified in this document may be used or developed in accordance with the control in this document. The control in this document prevails over any contrary or inconsistent provision in the Mornington Peninsula Planning Scheme. 2.0 PURPOSE The purpose of the control in this document is to allow the use and development of land for the purposes of the Peninsula Link (formerly known as the Frankston Bypass Project) and twin freeway service centres. 3.0 LAND The control in this document applies to all of the following: The land shown on Map 1 - Project Area Map of this Incorporated Document. This is referred to as the Peninsula Link Project Area for the purpose of this incorporated document. The land shown on Map 2 – being those parts of 129A Moorooduc Highway, Baxter comprising Lot 1 on PS 637226V (Vol 09516 Fol 959) required for the layout of twin freeway service centres as shown in map 2. This is referred to as the land shown in map 2 for the purpose of this incorporated document. 4.0 CONTROL Despite any provision to the contrary or any inconsistent provision in the Mornington Peninsula Planning Scheme, no -

Specification TCS

TCS 064 - 2019 Specification for the Supply and Installation of LUMS Gantry Identification System April 2019 Revision: Rev A TCS 064 - 2019 Foreword This specification has been developed by VicRoads. It is one of a number of technical specifications, and associated standard drawings, which set out the requirements for roadside ITS devices, traffic signal equipment and other electrical equipment and associated devices and control systems. This specification is intended for use in all relevant works undertaken by or on behalf of VicRoads. VicRoads Standard Drawings, Specifications and Guidelines are available for downloading from VicRoads website at the following address http://www.vicroads.vic.gov.au under Business & Industry > Technical documents search COPYRIGHT Specification updates. VicRoads specifications and associated standard © Road Corporation trading as drawings are subject to periodic review. To keep the specifications up to date, VicRoads. All rights reserved. amendments or new editions are issued as necessary. It is therefore important for users of VicRoads specifications to ensure that they have the latest version This document remains the and associated amendments. property of VicRoads. No part of this document may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including Intelligent Transport Systems photocopying, without the 60 Denmark Street Kew 3101 written permission of VicRoads Phone: (03) 9854 2103 Rev. A TCS 064 - 2019 PREFACE A. CHANGES TO THIS SPECIFICATION B.1 The main changes to this specification from the previous version are listed below: Version 1 updates made are as follows; • History table updated; • Colour requirements of signs updated; • Minimum connection details added; • Standard mounting options drawings added; • New Face Design added LUMS Gantry Numbering System Page 3 of 19 TCS 064 - 2019 Rev. -

Port of Hastings Development Project - Land Use Transport Corridor

Port of Hastings Development Authority 12-Sep-2014 Port of Hastings Development Project - Land Use Transport Corridor Land Use Planning Desktop Assessment Revision B – 12-Sep-2014 Prepared for – Port of Hastings Development Authority – ABN: 33 737 350 749 In May 2016 the Special Minister of State asked Infrastructure Victoria to provide advice on the future capacity of Victoria’s commercial ports. Specifically, the Minister has asked for advice on when the need for a second container port is likely to arise and which variables may alter this timeline. The Minister has also asked for advice on where a second container port would ideally be located and under what conditions, including the suitability of, and barriers to investing in, sites at the Port of Hastings and the Bay West location. In undertaking this task, Infrastructure Victoria reviewed work that was completed as part of the Port of Hastings development project before it was cancelled in 2014. This document forms part of the initial work undertaken for the proposed port development at Hastings. Infrastructure Victoria considers that much of the previous Hastings work, although preliminary in nature, is relevant and suitable for informing a strategic assessment. Therefore, Infrastructure Victoria has made the reports previously commissioned for the development project part of the evidence base on which Infrastructure Victoria will use in providing the Minister with advice. The opinions, conclusions and any recommendations in this document are based on conditions encountered and information reviewed at the date of preparation of the document and for the purposes of the Port of Hastings Development Project.