Gary Floyd Hovis 1961

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activités Sous La Pluie

Activités sous la pluie Bienvenue au Cœur de l’Ardenne, au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne dans les Communes d’Erezée, Houffalize, La Roche-en-Ardenne, Manhay et Rendeux. Seul, en couple, en famille, ou entre amis, toutes les saisons sont bonnes pour venir découvrir notre magnifique région, située en plein cœur de l’Ardenne belge. Le Cœur de l’Ardenne, au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne par temps de pluie ? « Chassons la grisaille ! » Vous êtes en vacances, il pleut et vous commencez à tourner en rond dans votre location ? Pas de soucis ! La Maison du Tourisme Cœur de l’Ardenne, au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne vous propose des activités et visites intérieures afin de profiter pleinement de votre séjour. Pictos dans cette Facebook PMR Access-i (niveau d’accessibilité) Coup de cœur pour les enfants Chien admis – Chien non-admis Attraction Touristique (soleils) Label Qualité service Wallonie Insolite Attractions et Centres d’interprétation TTA : Musée Vivant du Tram Vicinal Ardennais Rue du Pont d'Erezée 1 6997 Erezée T +32 (0)86 47 72 69 www.tta.be Départs & Prix : voir sur www.tta.be Tram spécial et/ou groupe sur demande. Cosmos ou l’Odysée du Saumon Rue du Val de l’Aisne 7 6997 Eveux (Erezée) uniquement sur réservation auprès de Riveo : T +32(0)84 41 35 71 - www.riveo.be Groupes : toute l’année sur réservation : 6€/pers. ou 9,50€ (avec une dégustation « surprise ») Individuels : Dates prévues en 2018 : 17/03 – 18/07 – 22/08 – 27/12 Prix : 6€/pers. -

Operation Overlord James Clinton Emmert Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2002 Operation overlord James Clinton Emmert Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Emmert, James Clinton, "Operation overlord" (2002). LSU Master's Theses. 619. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/619 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OPERATION OVERLORD A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by James Clinton Emmert B.A., Louisiana State University, 1996 May 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis could not have been completed without the support of numerous persons. First, I would never have been able to finish if I had not had the help and support of my wife, Esther, who not only encouraged me and proofed my work, but also took care of our newborn twins alone while I wrote. In addition, I would like to thank Dr. Stanley Hilton, who spent time helping me refine my thoughts about the invasion and whose editing skills helped give life to this paper. Finally, I would like to thank the faculty of Louisiana State University for their guidance and the knowledge that they shared with me. -

LES PLUS BELLES BALADES À PIED En Ardenne

LES PLUS BELLES BALADES À PIED LES PLUS BELLES Ce guide propose 50 promenades en boucle, adaptées à tous les marcheurs. BALADES À PIED Chaque promenade est introduite par une carte claire et précise, afin que vous puissiez vous repérer facilement. Et beaucoup suivent des sections en Ardenne en Ardenne de Sentiers de Grande Randonnée (GR) : ces sentiers suivent les routes et les chemins les plus intéressants. Le niveau de difficulté 2 et les distances 8 km (entre 5 et 20 km) varient. Chaque circuit est accompagné d’informations pratiques : point de départ, nature de la route, possibilités de stationnement, âge minimum requis 10 ans , niveau de difficulté 60 m , adresses pour se restaurer et boire un verre… En plus des sites incontournables et traditionnels, l’auteur nous fait découvrir des lieux naturels moins connus et des villages ardennais authentiques. L’auteur Julien Van Remoortere a parcouru, en famille et à pied, plus de 17 000 km au sud des vallées de la Sambre et de la Meuse afin de vous faire découvrir les plus beaux sentiers de randonnée. Il fut récompensé par des prix littéraires à plusieurs reprises. PIED À LES PLUS BELLES BALADES Cartes des balades téléchargeables sur www.racine.be 50 CIRCUITS EN BOUCLE EN FAMILLE 50 CIRCUITS EN BOUCLE EN FAMILLE JULIEN VAN REMOORTERE LES PLUS BELLES BALADES À PIED en Ardenne 50 CIRCUITS EN BOUCLE EN FAMILLE SOMMAIRE Se promener dans les Ardennes 9 Informations générales 16 Légendes des différents pictogrammes 19 LES BALADES » PROVINCE DE LIÈGE 1. Auel Panoramas grandioses le long de la frontière allemande 23 2. -

Rekruten Handbuch

As of 01 March 2018 www.wwiirc.org www.352-inf-div.org Page 2 of 46 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................ 3 Reenacting .......................................................... 4 Reenactor Guidelines ................................................ 6 Important Things to Keep In Mind ........................................ 6 Personal Goals .......................................................... 6 Requirements ............................................................ 6 Appearance .............................................................. 7 Safety .................................................................. 7 Vehicles ................................................................ 7 General Information ..................................................... 7 Casualty and POW Rules .............................................. 8 General Rules ........................................................... 8 Chain of Command .................................................... 9 Unit History ....................................................... 10 Division Composition ................................................... 10 Division Formation ..................................................... 13 The Atlantikwall ....................................................... 13 Battle in France ....................................................... 14 Battle in Holland ...................................................... 16 The 352nd Volksgrenadier-Division and the Ardennes Offensive -

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context Andrew Sangster Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy University of East Anglia History School August 2014 Word Count: 99,919 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or abstract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis explores the life and context of Kesselring the last living German Field Marshal. It examines his background, military experience during the Great War, his involvement in the Freikorps, in order to understand what moulded his attitudes. Kesselring's role in the clandestine re-organisation of the German war machine is studied; his role in the development of the Blitzkrieg; the growth of the Luftwaffe is looked at along with his command of Air Fleets from Poland to Barbarossa. His appointment to Southern Command is explored indicating his limited authority. His command in North Africa and Italy is examined to ascertain whether he deserved the accolade of being one of the finest defence generals of the war; the thesis suggests that the Allies found this an expedient description of him which in turn masked their own inadequacies. During the final months on the Western Front, the thesis asks why he fought so ruthlessly to the bitter end. His imprisonment and trial are examined from the legal and historical/political point of view, and the contentions which arose regarding his early release. -

Golden Lion Families Remember the Battle of the Bulge

Vol. 74 – No. 2 April – July 2018 Flag of Friendship — Golden Lion Families Remember the Battle of the Bulge A report from the Belgian Chapter by Carl Wouters, Association Belgium Liaison Burgermeister Christian Krings of St. Vith lays a wreath at the Division monument. He was awarded the 2017 Flag of Friendship for his support in organizing the commemorations (Photo Doug Mitchell/Borderlands Tours) in his town. December 16, 1944 is a date forever embedded in the memories of the veterans of the 106th Infantry Division. As the German Fifth Panzer Armee struck the lines of the U.S. 1st Army, heavy fighting engulfed the Golden Lions of the 106th on the heights of the Schnee Eifel and in the valleys of the Our River. Two months of bitter fighting followed, ending with the recapture of lost ground at the end of January 1945. Even though more than seven decades have passed since the 106th made a valiant stand at St. Vith, people from all over Europe continue to honor the men who served there, join in commemoration and perpetuation of their legacy. (Article continued on page 24) A tri-annualThe publication of the 106thCUB Infantry Division Association, Inc. Total Membership as of June 30, 2018 – 1,028 Membership includes CUB magazine subscription Annual Dues are no longer mandatory: Donations Accepted Payable to “106th Infantry Division Association” and mailed to the Treasurer — See address below Elected Offices President.............................Leon Goldberg (422/D) Past-President (Ex-Officio)...........Brian Welke (Associate Member) 1st Vice-President...............Wayne Dunn (Associate Member) 2nd Vice-President ...........Robert Schaffner (Associate Member) Adjutant: Memorial Chair: Randall M. -

Once in a Blue Moon: Airmen in Theater Command Lauris Norstad, Albrecht Kesselring, and Their Relevance to the Twenty-First Century Air Force

COLLEGE OF AEROSPACE DOCTRINE, RESEARCH AND EDUCATION AIR UNIVERSITY AIR Y U SIT NI V ER Once in a Blue Moon: Airmen in Theater Command Lauris Norstad, Albrecht Kesselring, and Their Relevance to the Twenty-First Century Air Force HOWARD D. BELOTE Lieutenant Colonel, USAF CADRE Paper No. 7 Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6615 July 2000 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Belote, Howard D., 1963– Once in a blue moon : airmen in theater command : Lauris Norstad, Albrecht Kesselring, and their relevance to the twenty-first century Air Force/Howard D. Belote. p. cm. -- (CADRE paper ; no. 7) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-58566-082-5 1. United States. Air Force--Officers. 2. Generals--United States. 3. Unified operations (Military science) 4. Combined operations (Military science) 5. Command of troops. I. Title. II. CADRE paper ; 7. UG793 .B45 2000 358.4'133'0973--dc21 00-055881 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. This CADRE Paper, and others in the series, is available electronically at the Air University Research web site http://research.maxwell.af.mil under “Research Papers” then “Special Collections.” ii CADRE Papers CADRE Papers are occasional publications sponsored by the Airpower Research Institute of Air University’s (AU) College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education (CADRE). Dedicated to promoting understanding of air and space power theory and application, these studies are published by the Air University Press and broadly distributed to the US Air Force, the Department of Defense and other governmental organiza- tions, leading scholars, selected institutions of higher learn- ing, public policy institutes, and the media. -

G2lllilc 1Ll'lllil

AD-A284IIINlDl!l il111111111 377 113ll !1 ANTI-ARMOR DEFENSE DATA STUDY (A2D2) DRAFT FINAL REPORT VOLUME I -- TECHNICAL REPORT DTIC (E ELECTEL AP 1 3 1994 i a tCp F An Employee-Owned Company #_oý94-29558 g2lllilC 1ll'lllil 1•o•.- SAIC RPT 90-xxxx ANTI-ARMOR DEFENSE DATA STUDY (A2D2) DRAFT FINAL REPORT, I -- TECHNICAL REPORT VOLUME UPiI 9, 1990 MARCH Victoria I. Young Charles M. Baily Joyce B. Boykin Lloyd J. Karamales James A. Wojcik Albert D. McJoynt (Consultant) PREPARED FOR AGENCY ARM4Y CONCEPTS ANALYSIS docuzent ýas been approved THE US UNDER This and s3ae; xit U for pubiic reie-se i .ziizited CONTRACT NUMBER MDA903-88-D-100 d0sribution DELIVERY ORDER 40 of the in this report are thoseofficial findings contained . .. do•k beyntudasotherof the Army authorsviews, and opinions,shoul and/or official Department "The not be construed as an dUld t her o Army or decision unless so bedesignated addressed to Director, US position, policy,Comments or suggestions should documentation 20814-2797. Woodmont Avenue, Bethesda, MD Concepts Analysis Agency, 8120 INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION SCIENCE APPLICATIONS Division Operations Analysis Military TI-7-2 1710 Goodridge Drive, McLean, Virginia 22102 CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE I Form ApprOed REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMBINo 0704.0188 __ExP Date Jun30 1986 RT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION lb RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS Unclassified None RITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 3 DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY OF REPORT NA 9%SSIFICATION /DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE NA RMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 5 MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) C 90- to be assigned - OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 16b. OFFICE SYMBOL 7a NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION :e Applications Intl Corp (if applicable) US Army Concepts Analysis Agency ESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b. -

German Army Group D OB West, 12 August 1942

German Army Group D "OB West" 12 August 1942 At Army Group's Disposal 100th Panzer Brigade 2/202nd Panzer Regiment In the Netherlands: 38th Division: 1/,2/,3/108th Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/112th Infantry Regiment 138th Schnell Battalion 1/,2/,3/138th Artillery Regiment 138th Pioneer Battalion 138th Signals Battalion 138th Division (Einheiten) Support Units 167th Division: 1/,2/,3/315th Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/331st Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/339th Infantry Regiment 238th Panzerjäger Battalion 238th Bicycle Battalion 1/,2/,3/,4/238th Artillery Regiment 238th Pioneer Battalion 238th Signals Battalion 238th Division (Einheiten) Support Units 719th Division: 1/,2/,3/723rd Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/743rd Infantry Regiment Panzerjäger Company 663rd Artillery Battalion 719th Pioneer Company 719th Signals Battalion 719th Division (Einheiten) Support Units 15th Army At Army's Disposal: 10th Panzer Division: 1/,2/7th Armored Regiment 10th Panzer Grenadier Brigade 1/,2/,3/69th Panzer Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/,3/86th Panzer Grenadier Regiment 90th Panzerjäger Battalion 90th Motorcycle Battalion 1/,2/,3/,4/90th Artillery Regiment 90th Signals Battalion 46th Pioneer Battalion 90th Division (Einheiten) Support Units SS Leibstandarte Adolph Hitler 1/,2/,3/1st SS LSSAH Motorized Infantry Regiment 1/,2/,3/2nd SS LSSAH Motorized Infantry Regiment SS Leibstandarte Adolph Hitler Sturmgeschütz Battalion SS Leibstandarte Adolph Hitler Armored Troop SS Leibstandarte Adolph Hitler Motorcycle Regiment 1 1/,2/,3/,4/SS Leibstandarte Adolph Hitler (mot) Artillery -

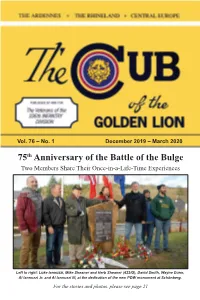

75Th Anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge Two Members Share Their Once-In-A-Life-Time Experiences

Vol. 76 – No. 1 December 2019 – March 2020 75th Anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge Two Members Share Their Once-in-a-Life-Time Experiences Left to right: Luke Iannuzzi, Mike Sheaner and Herb Sheaner (422/G), David Smith, Wayne Dunn, Al Iannuzzi Jr. and Al Iannuzzi III, at the dedication of the new POW monument at Schönberg. For the stories and photos, please see page 21 A tri-annualThe publication of the 106thCUB Infantry Division Association, Inc. Total Membership as of January 31, 2020 – 981 Membership includes CUB magazine subscription Annual Dues are no longer mandatory: Donations Accepted Payable to “106th Infantry Division Association” and mailed to the Treasurer — See address below Elected Offices President............................. Bob Pope (590/FABN) Past-President (Ex-Officio)..........Wayne Dunn (Associate Member) 1st Vice-President............Robert Schaffner (Associate Member) 2nd Vice-President ...............Janet Wood (Associate Member) 3rd Vice-President .............Henry LeClair (Associate Member) Adjutant: Memorial Chair: Randall M. Wood (Associate member) Dr. John G. Robb (422/D) 810 Cramertown Loop, 238 Devore Dr., Meadville, PA 16355 Martinsville, IN 46151 [email protected] [email protected] 814-333-6364 765-346-0690 ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- Chaplain: Pastor Chris Edmonds Business Matters, Deaths, 206 Candora Rd., Maryville, TN 37804 Address changes to: [email protected] Membership: 865-599-6636 Jacquelyn Coy ---------------------------------------- 121 McGregor Ave., 106th ID Assn’s Belgium Liaison: Mt. Arlington, NJ 07856 Carl Wouters [email protected] Waterkant 17 Bus 32, B-2840 Terhagen, Belgium 973-663-2410 [email protected] cell: +(32) 47 924 7789 Donations, checks to: ---------------------------------------- Treasurer: 106th Assoc. Website Webmaster: Mike Sheaner Wayne G. -

PARKER's CROSSROADS: the ALAMO DEFENSE

PARKER'S CROSSROADS: The ALAMO DEFENSE By Sergeant First Class (Ret.) Richard Raymond III Although the following article was written about our battalion, and is factually true, I can assure you that the Alamo was never on anybody’s mind at the time. "Surviving" is the name of the game. We had no idea what we were to face when the showdown came. John Schaffner 106th Division Association Historian ************************************************************** The following appeared in the August 1993 issue of the magazine "Field Artillery". It was written by Sgt. First Class (retired) Richard Raymond III. He won 2nd Place in the US Field Artillery Association's 1993 History Writing Contest with this article. He's a 1954 graduate of the US Naval Academy at Annapolis and served in the Marine Corps, discharged as a 1st Lt. in 1960. Eight years later, Sgt. 1st Class Raymond served with the National Guard Field Artillery units in Connecticut, North Carolina & Virginia. His experience with Field Artillery includes serving as Fire Direction Center Chief, A Battery, 1st Battalion, 113 Field Artillery, Norfolk, Virginia. His last assignment was as Brigade Intelligence Sergeant, 2nd Brigade, 29th Infantry Division in Bowling Green, Va., before he retired from the Army in 1990. He has published military history articles in "Soldiers" and "Army" magazines and won the US Army Forces Command "Fourth Estate" Award for military journalism in 1983. ***************************** PARKER'S CROSSROADS: The ALAMO DEFENSE By Sergeant First Class (Ret.) Richard Raymond III The tactical situation may require a rigid defense of a fixed position. Such a defense, if voluntarily adopted, requires the highest degree of tactical skill and leadership. -

Record Copy to Be Retired When \\O Longer©Needed

D J 739 MS # C-065a /? aao.C <- * - c.l Fgn MS English Copy GBEIMER_pIABY_MpjgES, 12 Aug 1942 - 12 Mar 1943 RECORD COPY TO BE RETIRED WHEN \\O LONGER©NEEDED flROPSRTY OF US ARMY HISTORICAL DIVISION HEADQUARTERS, UNITED STATES ARMY EUROPE FOREIGN MILITARY STUDIES BRANCH MS # C-065a Helmuth GREENER Ministerialrat Custodian of the War Diary in HITLER©S Headquarters (August 1939 - April 1943) NOTES on the Situation Reports and Discussions at HITLER©S Headquarters from 12 August 1942 to 1? March 1943 Translator: Werner METER Editor : LUCAS Reviewer : Lt. Col. VERNON HISTORICAL DIVISION EUROPEAN COl-iMAND MS # C~065 a FOBStfOBD This manuscript is part of a narrative history of events in the German Armed Forces Supreme Command Headquarters during World War II. The writer, Hell- Mith G-BSINM, was charged with writing the War Diary at that headquarters from August 1939 to April 22, 1942. He has based hie work on notes taken at various conferences, copies of final drafts for entry in the War Diary, copies of HIJLER©S directives, orders end documents he was able to save from destruction at great personal risk. With the aid of these sources and the trained mind and memory of a professional historian, he has presented a vivid picture of HITLilR© S method of com mand as well as his reaction to reverses end success and the various other factors which influenced de cisions in both the military and the political spheres. In addition to a general description of procedures in the supreme headquarters it includes details of or ganization and the composition of HITLER©S immediate staff.