PARKER's CROSSROADS: the ALAMO DEFENSE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activités Sous La Pluie

Activités sous la pluie Bienvenue au Cœur de l’Ardenne, au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne dans les Communes d’Erezée, Houffalize, La Roche-en-Ardenne, Manhay et Rendeux. Seul, en couple, en famille, ou entre amis, toutes les saisons sont bonnes pour venir découvrir notre magnifique région, située en plein cœur de l’Ardenne belge. Le Cœur de l’Ardenne, au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne par temps de pluie ? « Chassons la grisaille ! » Vous êtes en vacances, il pleut et vous commencez à tourner en rond dans votre location ? Pas de soucis ! La Maison du Tourisme Cœur de l’Ardenne, au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne vous propose des activités et visites intérieures afin de profiter pleinement de votre séjour. Pictos dans cette Facebook PMR Access-i (niveau d’accessibilité) Coup de cœur pour les enfants Chien admis – Chien non-admis Attraction Touristique (soleils) Label Qualité service Wallonie Insolite Attractions et Centres d’interprétation TTA : Musée Vivant du Tram Vicinal Ardennais Rue du Pont d'Erezée 1 6997 Erezée T +32 (0)86 47 72 69 www.tta.be Départs & Prix : voir sur www.tta.be Tram spécial et/ou groupe sur demande. Cosmos ou l’Odysée du Saumon Rue du Val de l’Aisne 7 6997 Eveux (Erezée) uniquement sur réservation auprès de Riveo : T +32(0)84 41 35 71 - www.riveo.be Groupes : toute l’année sur réservation : 6€/pers. ou 9,50€ (avec une dégustation « surprise ») Individuels : Dates prévues en 2018 : 17/03 – 18/07 – 22/08 – 27/12 Prix : 6€/pers. -

LES PLUS BELLES BALADES À PIED En Ardenne

LES PLUS BELLES BALADES À PIED LES PLUS BELLES Ce guide propose 50 promenades en boucle, adaptées à tous les marcheurs. BALADES À PIED Chaque promenade est introduite par une carte claire et précise, afin que vous puissiez vous repérer facilement. Et beaucoup suivent des sections en Ardenne en Ardenne de Sentiers de Grande Randonnée (GR) : ces sentiers suivent les routes et les chemins les plus intéressants. Le niveau de difficulté 2 et les distances 8 km (entre 5 et 20 km) varient. Chaque circuit est accompagné d’informations pratiques : point de départ, nature de la route, possibilités de stationnement, âge minimum requis 10 ans , niveau de difficulté 60 m , adresses pour se restaurer et boire un verre… En plus des sites incontournables et traditionnels, l’auteur nous fait découvrir des lieux naturels moins connus et des villages ardennais authentiques. L’auteur Julien Van Remoortere a parcouru, en famille et à pied, plus de 17 000 km au sud des vallées de la Sambre et de la Meuse afin de vous faire découvrir les plus beaux sentiers de randonnée. Il fut récompensé par des prix littéraires à plusieurs reprises. PIED À LES PLUS BELLES BALADES Cartes des balades téléchargeables sur www.racine.be 50 CIRCUITS EN BOUCLE EN FAMILLE 50 CIRCUITS EN BOUCLE EN FAMILLE JULIEN VAN REMOORTERE LES PLUS BELLES BALADES À PIED en Ardenne 50 CIRCUITS EN BOUCLE EN FAMILLE SOMMAIRE Se promener dans les Ardennes 9 Informations générales 16 Légendes des différents pictogrammes 19 LES BALADES » PROVINCE DE LIÈGE 1. Auel Panoramas grandioses le long de la frontière allemande 23 2. -

Golden Lion Families Remember the Battle of the Bulge

Vol. 74 – No. 2 April – July 2018 Flag of Friendship — Golden Lion Families Remember the Battle of the Bulge A report from the Belgian Chapter by Carl Wouters, Association Belgium Liaison Burgermeister Christian Krings of St. Vith lays a wreath at the Division monument. He was awarded the 2017 Flag of Friendship for his support in organizing the commemorations (Photo Doug Mitchell/Borderlands Tours) in his town. December 16, 1944 is a date forever embedded in the memories of the veterans of the 106th Infantry Division. As the German Fifth Panzer Armee struck the lines of the U.S. 1st Army, heavy fighting engulfed the Golden Lions of the 106th on the heights of the Schnee Eifel and in the valleys of the Our River. Two months of bitter fighting followed, ending with the recapture of lost ground at the end of January 1945. Even though more than seven decades have passed since the 106th made a valiant stand at St. Vith, people from all over Europe continue to honor the men who served there, join in commemoration and perpetuation of their legacy. (Article continued on page 24) A tri-annualThe publication of the 106thCUB Infantry Division Association, Inc. Total Membership as of June 30, 2018 – 1,028 Membership includes CUB magazine subscription Annual Dues are no longer mandatory: Donations Accepted Payable to “106th Infantry Division Association” and mailed to the Treasurer — See address below Elected Offices President.............................Leon Goldberg (422/D) Past-President (Ex-Officio)...........Brian Welke (Associate Member) 1st Vice-President...............Wayne Dunn (Associate Member) 2nd Vice-President ...........Robert Schaffner (Associate Member) Adjutant: Memorial Chair: Randall M. -

G2lllilc 1Ll'lllil

AD-A284IIINlDl!l il111111111 377 113ll !1 ANTI-ARMOR DEFENSE DATA STUDY (A2D2) DRAFT FINAL REPORT VOLUME I -- TECHNICAL REPORT DTIC (E ELECTEL AP 1 3 1994 i a tCp F An Employee-Owned Company #_oý94-29558 g2lllilC 1ll'lllil 1•o•.- SAIC RPT 90-xxxx ANTI-ARMOR DEFENSE DATA STUDY (A2D2) DRAFT FINAL REPORT, I -- TECHNICAL REPORT VOLUME UPiI 9, 1990 MARCH Victoria I. Young Charles M. Baily Joyce B. Boykin Lloyd J. Karamales James A. Wojcik Albert D. McJoynt (Consultant) PREPARED FOR AGENCY ARM4Y CONCEPTS ANALYSIS docuzent ýas been approved THE US UNDER This and s3ae; xit U for pubiic reie-se i .ziizited CONTRACT NUMBER MDA903-88-D-100 d0sribution DELIVERY ORDER 40 of the in this report are thoseofficial findings contained . .. do•k beyntudasotherof the Army authorsviews, and opinions,shoul and/or official Department "The not be construed as an dUld t her o Army or decision unless so bedesignated addressed to Director, US position, policy,Comments or suggestions should documentation 20814-2797. Woodmont Avenue, Bethesda, MD Concepts Analysis Agency, 8120 INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION SCIENCE APPLICATIONS Division Operations Analysis Military TI-7-2 1710 Goodridge Drive, McLean, Virginia 22102 CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE I Form ApprOed REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMBINo 0704.0188 __ExP Date Jun30 1986 RT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION lb RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS Unclassified None RITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 3 DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY OF REPORT NA 9%SSIFICATION /DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE NA RMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 5 MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) C 90- to be assigned - OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 16b. OFFICE SYMBOL 7a NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION :e Applications Intl Corp (if applicable) US Army Concepts Analysis Agency ESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b. -

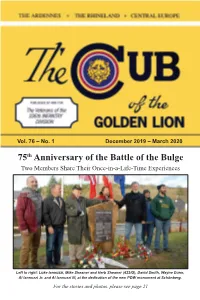

75Th Anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge Two Members Share Their Once-In-A-Life-Time Experiences

Vol. 76 – No. 1 December 2019 – March 2020 75th Anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge Two Members Share Their Once-in-a-Life-Time Experiences Left to right: Luke Iannuzzi, Mike Sheaner and Herb Sheaner (422/G), David Smith, Wayne Dunn, Al Iannuzzi Jr. and Al Iannuzzi III, at the dedication of the new POW monument at Schönberg. For the stories and photos, please see page 21 A tri-annualThe publication of the 106thCUB Infantry Division Association, Inc. Total Membership as of January 31, 2020 – 981 Membership includes CUB magazine subscription Annual Dues are no longer mandatory: Donations Accepted Payable to “106th Infantry Division Association” and mailed to the Treasurer — See address below Elected Offices President............................. Bob Pope (590/FABN) Past-President (Ex-Officio)..........Wayne Dunn (Associate Member) 1st Vice-President............Robert Schaffner (Associate Member) 2nd Vice-President ...............Janet Wood (Associate Member) 3rd Vice-President .............Henry LeClair (Associate Member) Adjutant: Memorial Chair: Randall M. Wood (Associate member) Dr. John G. Robb (422/D) 810 Cramertown Loop, 238 Devore Dr., Meadville, PA 16355 Martinsville, IN 46151 [email protected] [email protected] 814-333-6364 765-346-0690 ---------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------- Chaplain: Pastor Chris Edmonds Business Matters, Deaths, 206 Candora Rd., Maryville, TN 37804 Address changes to: [email protected] Membership: 865-599-6636 Jacquelyn Coy ---------------------------------------- 121 McGregor Ave., 106th ID Assn’s Belgium Liaison: Mt. Arlington, NJ 07856 Carl Wouters [email protected] Waterkant 17 Bus 32, B-2840 Terhagen, Belgium 973-663-2410 [email protected] cell: +(32) 47 924 7789 Donations, checks to: ---------------------------------------- Treasurer: 106th Assoc. Website Webmaster: Mike Sheaner Wayne G. -

Guide De La Pêche Au Coeur De L'ardenne

Le guide de la pêche au coeur de l’Ardenne belge Préface L’Ardenne belge présente depuis toujours un attrait indéniable pour la pêche. Rivières préservées, lacs de barrage et pêcheries artisanales offrent aux pêcheurs de nombreuses possibilités d’exercer leur passe-temps favori. Qui plus est, au milieu de paysages magnifiques et d’une nature protégée. Deux Parcs Naturels, celui de la Haute-Sûre Forêt d’Anlier et celui des Deux Ourthes, recouvrent d’ailleurs une partie importante du territoire ardennais. Parmi leurs missions, la promotion d’un tourisme de qualité basé sur les ressources patrimoniales de leur territoire. Conscients de la richesse halieutique de leur territoire, les deux Parcs Naturels ont réalisé cette brochure en collaboration avec les différentes Maisons de Tourisme et Syndicats d’Initiative, ainsi que la Fédération Sportive des Pêcheurs Francophones de Belgique. De Gouvy à Habay, ce livret présente, cartes à l’appui, les parcours des différentes sociétés de pêche en rivière, mais aussi les plans d’eau, les hébergements « pêche » et les commerces spécialisés de ce vaste territoire, environ 200.000 hectares ! A l’aide de pictogrammes et d’explications claires, le pêcheur désirant visiter cette belle région trouvera toutes les informations nécessaires pour préparer un séjour des plus réussi ! N’hésitez pas à consulter aussi le site http://peche.tourisme.wallonie.be. A la mouche ou au lancer, le long de la Sûre ou de l’Ourthe, seul ou entre amis, venez découvrir les nombreuses possibilités de pêche au cœur de l’Ardenne ! -

Les Plus Belles Balades En Ardenne Au Fil De L’Eau

PIERRE PAUQUAY LES PLUS BELLES BALADES EN ARDENNE AU FIL DE L’EAU 12 BOUCLES EN FAMILLE À VÉLO LÉGENDES DES PICTOGRAMMES Âge à partir duquel la balade est conseillée 12 ans Dénivelé Patrimoine 145 m Distance Dossier à thème 32 km Durée Nature 2 h 30 SOMMAIRE 1. La Roche-en-Ardennes Là-bas coule une rivière… ............................................................................................................................................. 11 2. Saint-Hubert Le grand vert ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 29 3. Redu Un itinéraire de légendes .............................................................................................................................................. 43 4. Treignes Bienvenue dans le Sud ! ................................................................................................................................................... 57 5. Vresse-sur-Semois Quand la Semois devient Semoy ..................................................................................................................... 71 6. Bouillon Terre d’épopées .............................................................................................................................................................................. 87 7. Herbeumont La course vers la Gaume ............................................................................................................................................... -

Parker's Crossroads

Historical Overview On 19 December 1944 a small artillery column led by Major Arthur C. Parker, having already escaped the disaster of Schnee Eiffel and the capture of Saint Vith, was ordered to take up position at the strategic crossroads of Baraque de Fraiture. Parker learned that he was now under the command of XVIII (Airborne) Corps and that reinforcements would be sent to him as soon as they became available. Parker's men set up a defensive perimeter with their three remaining 105mm howitzers and were soon reinforced by elements of the 87th Cavalry Squadron and 203rd Antiaircraft Auto-Weapons Battalion of the 7th Armoured Division. After some skirmishing with advance guard elements of 560. Volksgrenadiere Division, Parker asked permission to withdraw, receiving instead an order from to "Stand and Resist". On 22 December, reinforcements arrived at "Parker's Crossroads"; eleven M4 Sherman tanks and two M7 Priest self-propelled \ guns from Task Force Kane (3rd Armoured Division), four M18 Hellcat Tank Destroyers from 643rd Tank Destroyer Battalion (3rd Armoured Division), a detachment of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion and Company 'F', 325th Glider Infantry Regiment (82nd Airborne Division), led by Captain Junior R. Woodruff. As a strategic position on the Highway N15 to Liège, Baraque de Fraiture was a prime target for 2. SS Panzer Division "Das Reich", who wanted to break through to the Ourthe Valley and from there to the Meuse. The task of crushing American resistance at Baraque de Fraiture was allocated to SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Weidinger and his SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 4 "Der Führer". -

[email protected] // 00800/72 83 55 42 // +32 78 15 15 15

Map Latitude Longitude Latitude Longitude BELGIUM 1 TOTAL Waarloos Autosnelweg E19 Brussel Antwerpen 51° 5' 53.3862" N 4° 26' 17.7858" E 51.098163 4.438274 2 Parking Maasmechelen E314 - Borseem (dir. Belgium) 50° 57' 5.4108" N 5° 43' 18.4116" E 50.9516700 5.7236500 3 TEXACO Leuven/Heverlee Heverlee Noord A3/E40Brussel - 3001 Leuven (Heverlee) 50.8536700 4.6590100 4 TOTAL Hoegaarden E40 Brussel - Luik 50° 45' 10.4394" N 4° 57' 5.9322" E 50.753131 4.951380 5 SHELL Cerexhe-Heuseúx Autoroute Dir. Aachen E40 50° 39' 15.6234" N 5° 42' 32.6232" E 50.6535300 5.7083000 6 TOTAL Lichtenbusch E40/A3 dir. Liège 50° 43' 6.546" N 6° 7' 6.2538" E 50.7181300 6.1190500 7 Q8 Gembloux / Aisch E411 Wavre - Namur 50° 35' 58.4592" N 4° 47' 25.8462" E 50.5995700 4.7901200 8 TOTAL Wanlin Autoroute E411 LUX.- BRUXELLES 50.1440370 5.0796760 9 TOTAL Nivelles Aire D Orival East A7-E19 Mons-Brussels 50.6157000 4.2995500 10 Q8 Le Roeulx / Thieu E19 Mons > BXL 50° 29' 17.3466" N 4° 5' 48.4872" E 50.4880700 4.0957500 11 TEXACO Saint-Ghislain Aire de Saint-Ghislain (Nord)A7/E19/E42 Mons > Paris 50.4525650 3.8032310 12 SHELL Wetteren E40 Gent > BXL (Zuid) 50° 58' 8.652" N 3° 50' 29.886" E 50.9696660 3.8422910 13 Q8 Ranst E34 Antwerpen - Turnhout (Zuid)(in direction Hasselt) 51.2078610 4.5494410 14 Q8 Verlaine Verlaine ZuidA15/E42 Charleroi-Liege 50.5920650 5.3030940 15 TEXACO Mannekensvere Area de Mannekensvere NordA18/E40 Brugge-Calais 51.1356990 2.8200490 16 Q8 Sprimont E25 Bastogne > Liège 50.5239090 5.6668880 17 TOTAL Zeebrugge Baron de Maerelaan 95 51.320856 3.186167 -

Mayoral Speech, Manhay, Belgium - Wednesday, June 2, 2004

MAYORAL SPEECH, MANHAY, BELGIUM - WEDNESDAY, JUNE 2, 2004 Messrs the Governors, Messrs the Burgomasters, Messrs the elected members, Ladies and Messrs the Counsellors, Messrs the Officers and Soldiers, Messrs the Ex-servicemen, Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Friends, It's an honour to greet you in Manhay, for the commemoration of the 60th birthday of the Battle of the Bulge. The academic part of this manifestation is going to take place not far from here, at the former train station where we will go all together in a few minutes. Then, we're going to unveil the commemorative tablet, in homage to the soldiers of the third Battalion of the 517th Paratrooper Infantry Regiment.The children will give roses to the Veterans, and we will decorate with flowers the new commemorative tablet After this we will join the village hall where will be hold a reception in honour. There you'll be able to see an exposition that has been organised by the committee of Manhay. Finally, our American guests are going to rejoin their coaches that will bring them to their respective municipalities to continue their visits. Before starting, let us meditate a few minutes in front of this memorial stone, which has been raised in remember to those who fought for our liberty. (Depot d'une gerbe) I'll ask now to the children of our primary schools to open the way. - 1 - MAYORAL SPEECH, MANHAY, BELGIUM - WEDNESDAY, JUNE 2, 2004 60?me anniversaire de la bataille des Ardennes I don't have known the war and a lot of people here are in the same situation as me. -

Toeristische Gids

NL EREZÉE • HOUFFALIZE • LA ROCHE-EN-ARDENNE • MANHAY • RENDEUX TOERISTISCHE GIDS Kies voor de streek Deze toeristische gids is van Cœur de l’Ardenne, een uitnodiging om een streek au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne en ontdek een te ontdekken die gezegend is met prachtig gebied waar een opmerkelijke en gulle natuur ... u graag een halte zult houden. Laat u verleiden door de schoonheid van de natuur, de uitzichten en de landschappen van de 5 gemeentes die deel uitmaken van de streek “Cœur de l’Ardenne, au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne » (Erezée, Houffalize, La Roche-en-Ardenne, Manhay et Rendeux). Deze gids zal u helpen om uw daguitstap of uw verblijf bij ons, beter voor te bereiden. Bovendien is het ook een uitnodiging om een paradijs te ontdekken voor wandelaars, fietsers, lekkerbekken, vakantiegangers die een kwaliteitsverblijf wensen, gepassioneerden van typische karakterdorpjes en tradities, en liefhebbers van attracties en ontspanning. Bénédicte WATHY en Audrey CARLIER coördinatoren Zich ontspannen Erfgoed Gastronomie 4 WE VERMAKEN ONS, 20 ARCHITECTURAAL EN 26 RESTAURANTS WE ONTDEKKEN HISTORISCH ERFGOED 38 PICKNICKPLAATSEN, 8 SPORTIEVE ACTIVITEITEN WEKELIJKSE MARKTEN 12 AV R eL 22 NATUURLIJK ERFGOED & SPEELTUINEN 14 TREKTOCHTEN Heeft u meer informatie nodig ? De medewerkers van het “Maison du Tourisme”zijn tot uw beschikking. Aarzel niet en kom ons een bezoek Toegang & mobiliteit brengen! ROUTES E411 : BRUXELLES - ARLON - LUXEMBOURG © J-M Bodelet (UITGANG 18, N4 : MARCHE-EN-FAMENNE) E25 : LIÈGE - ARLON - LUXEMBOURG (UITGANG 50 BARAQUE DE FRAITURE N89) Elke overname uit deze brochure, zelfs gedeeltekijk, is strikt verboden zonder schriftelijk toestemming van « la Maison N4 : NAMUR - ARLON du Tourisme Cœur de l’Ardenne, au fil de l’Ourthe & de l’Aisne » vzw. -

WALLONIABELGIUM the Battle of the ARDENNES Down Memory Lane

WALLONIABELGIUM The Battle of the ARDENNES Down Memory Lane WALLONIA. ENJOY A WARM-HEARTED WELCOME. www.wallonia-tourism.be E 17 AALST ROESELARE 6 21 6 18 19 12 20 7 2 5 19a 18 8 3 5 E 40 9 17 20 10 LEUVENE A 17 21 KORTRIJK 11 E 40 15 6 4 3 9 21 22 5 1 10 13 2 23 2 11 3 14 BRUXELLES 5 12 1 2 15a 16 BRUSSEL 5 17 1 2 13 HAMME 14 MILLE 17 3 MOUSCRON4 15 OING 4 3 FLOBECQ GREZ-DOICEAU 16 WAVRE ELLEZELLES 5 23 GENVAL 23 WATERLOO 6 LESSINES ENGHIEN R 0 BRABA 7 27 RIXENSART 8 26 25 24 17 ROUBAIX 28 A 8 WALLO 32 LOUVAIN-LA-NEUVE E 17 CORROY- 2 ITTRE 20 A 8 REBECQ 19 OTTIGNIES 9 LE GRAND 34 33 ATH 18 TOURNAI E 19 P BRAINE- 11 35 BLICQUY- BRUGELETTE LE COMTE RONQUIÈRES 32 AUBECHIES LEUZE-EN- CAMBRON- SOIGNIES 19 LILLEE 31 HAINAUT CASTEAU NIVELLES VILLERS- LA-VILLE ANTOING ECAUSSINES 20 GEMBLOUX 30 HAINAUT A 54 E 42 20 LENS FELUY SENEFFE 29 BELŒIL 3 PÉRUWELZ 28 21 20 2 21 19 13 12 27 BAUDOUR 23 22 E 42 RRAS 18 GODARVILLE 14 E 42 STRÉPY-THIEU 17 16 26 24 LA LOUVIERE 15 NNAMUR 24a 1 25 26 BOIS MORLANWELZ 24 DU LUC 13 GRAND MONS 12 2 HORNU FONTAINE 26 11 W E 19 L’EVÊQUE 3 BINCHE 10 PROFO 9 4 FOSSES- 5 6 CHARLEROI LE-VILLE VALENCIENNES ANNEVOI ROISIN MARCINELLE THUIN METTET MAREDSOUS WALCOURT FALAËN MAUBEUGE FRANCE FLORENNES BEAUMONT SILENRIEUX AN BOUSSU PHILIPPEVILLE NAMUR LACS DE L'EAU D'HEURE F HASTIER FROIDCHAPELLE CERFONTAINE RANCE SAUTIN VIRELLES MARIEMBOURG NISMES CHIMAY PETIGNY MOMIGNIES COUVIN 1 BAILEUX OIGNIES EN GREAT BRITAIN THIERACHE ARNHEM LONDON NORTH SEA NIJMEGEN DOVER NEDERLAND CALAIS BRUXELLES ENGLISH AACHEN MONS CHANNEL REMAGEN FRANCE