The Making of Tupaia's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endeavour Anniversary

Episode 10 Teacher Resource 28th April 2020 Endeavour Anniversary Students will investigate Captain Endeavour History Cook’s voyage to Australia on 1. When did the Endeavour set sail from England? board the HMB Endeavour. Students will explore the impact 2. Who led the voyage of discovery on the Endeavour? that British colonisation had on 3. Describe James Cook’s background. the lives of Aboriginal and Torres 4. What did Cook study that would help him to become a ship’s Strait Islander Peoples. captain? 5. Fill in the missing words: By the 18th Century, _________________ had been mapping the globe for centuries, claiming HASS – Year 4 ______________ and resources as their own. (Europeans and land) The journey(s) of AT LEAST ONE 6. Who was Joseph Banks? world navigator, explorer or trader 7. Why did Banks want to travel on the Endeavour? up to the late eighteenth century, including their contacts with other 8. The main aim of the voyage was to travel to… societies and any impacts. 9. What rare event was the Endeavour crew aiming to observe? 10. What was their secret mission? The nature of contact between 11. Who was Tupaia? Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and others, for 12. After leaving Tahiti, where did the Endeavour go? example, the Macassans and the 13. What happen in April 1770? Europeans, and the effects of 14. Complete the following sentence. Australia was known to Europeans these interactions on, for at the time as New___________________. (Holland) example, people and environments. 15. Describe the first contact with Indigenous people. -

Cook Islands of the Basicbasic Informationinformation Onon Thethe Marinemarine Resourcesresources Ofof Thethe Cookcook Islandsislands

Basic Information on the Marine Resources of the Cook Islands Basic Information on the Marine Resources of the Cook Islands Produced by the Ministry of Marine Resources Government of the Cook Islands and the Information Section Marine Resources Division Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) with financial assistance from France . Acknowledgements The Ministry of Marine Resources wishes to acknowledge the following people and organisations for their contribution to the production of this Basic Information on the Marine Resources of the Cook Islands handbook: Ms Maria Clippingdale, Australian Volunteer Abroad, for compiling the information; the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project for allowing some of its data to be used; Dr Mike King for allowing some of his drawings and illustration to be used in this handbook; Aymeric Desurmont, Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) Fisheries Information Specialist, for formatting and layout and for the overall co-ordination of efforts; Kim des Rochers, SPC English Editor for editing; Jipé Le-Bars, SPC Graphic Artist, for his drawings of fish and fishing methods; Ministry of Marine Resources staff Ian Bertram, Nooroa Roi, Ben Ponia, Kori Raumea, and Joshua Mitchell for reviewing sections of this document; and, most importantly, the Government of France for its financial support. iii iv Table of Contents Introduction .................................................... 1 Tavere or taverevere ku on canoes ................................. 19 Geography ............................................................................ -

Human Discovery and Settlement of the Remote Easter Island (SE Pacific)

quaternary Review Human Discovery and Settlement of the Remote Easter Island (SE Pacific) Valentí Rull Laboratory of Paleoecology, Institute of Earth Sciences Jaume Almera (ICTJA-CSIC), C. Solé i Sabarís s/n, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Received: 19 March 2019; Accepted: 27 March 2019; Published: 2 April 2019 Abstract: The discovery and settlement of the tiny and remote Easter Island (Rapa Nui) has been a classical controversy for decades. Present-day aboriginal people and their culture are undoubtedly of Polynesian origin, but it has been debated whether Native Americans discovered the island before the Polynesian settlement. Until recently, the paradigm was that Easter Island was discovered and settled just once by Polynesians in their millennial-scale eastward migration across the Pacific. However, the evidence for cultivation and consumption of an American plant—the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas)—on the island before the European contact (1722 CE), even prior to the Europe-America contact (1492 CE), revived controversy. This paper reviews the classical archaeological, ethnological and paleoecological literature on the subject and summarizes the information into four main hypotheses to explain the sweet potato enigma: the long-distance dispersal hypothesis, the back-and-forth hypothesis, the Heyerdahl hypothesis, and the newcomers hypothesis. These hypotheses are evaluated in light of the more recent evidence (last decade), including molecular DNA phylogeny and phylogeography of humans and associated plants and animals, physical anthropology (craniometry and dietary analysis), and new paleoecological findings. It is concluded that, with the available evidence, none of the former hypotheses may be rejected and, therefore, all possibilities remain open. -

Sacred Kingship: Cases from Polynesia

Sacred Kingship: Cases from Polynesia Henri J. M. Claessen Leiden University ABSTRACT This article aims at a description and analysis of sacred kingship in Poly- nesia. To this aim two cases – or rather island cultures – are compared. The first one is the island of Tahiti, where several complex polities were found. The most important of which were Papara, Te Porionuu, and Tautira. Their type of rulership was identical, so they will be discussed as one. In these kingdoms a great role was played by the god Oro, whose image and the belonging feather girdles were competed fiercely. The oth- er case is found on the Tonga Islands, far to the west. Here the sacred Tui Tonga ruled, who was allegedly a son of the god Tangaloa and a woman from Tonga. Because of this descent he was highly sacred. In the course of time a new powerful line, the Tui Haa Takalaua developed, and the Tui Tonga lost his political power. In his turn the Takalaua family was over- ruled by the Tui Kanokupolu. The tensions between the three lines led to a fierce civil war, in which the Kanokupolu line was victorious. The king from this line was, however, not sacred, being a Christian. 1. INTRODUCTION Polynesia comprises the islands situated in the Pacific Ocean within the triangle formed by the Hawaiian Islands, Easter Island and New Zealand. The islanders share a common Polynesian culture. This cultural unity was established already in the eighteenth century, by James Cook, who ob- served during his visit of Easter Island in 1774: In Colour, Features, and Languages they [the Easter Islanders] bear such an affinity to the People of the more Western isles that no one will doubt that they have the same Origin (Cook 1969 [1775]: 279, 354–355). -

The Conflict Between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in the Navigation of Polynesia

Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 48 “When earth and sky almost meet”: The Conflict between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in Polynesian Navigation. Luke Strongman1 Abstract This paper provides an account of the differing ontologies of Polynesian and European navigation techniques in the Pacific. The subject of conflict between traditional knowledge and modernity is examined from nine points of view: The cultural problematics of textual representation, historical differences between European and Polynesian navigation; voyages of re-discovery and re-creation: Lewis and Finney; How the Polynesians navigated in the Pacific; a European history of Polynesian navigation accounts from early encounters; “Earth and Sky almost meet”: Polynesian literary views of recovered knowledge; lost knowledge in cultural exchanges – the parallax view; contemporary views and lost complexities. Introduction Polynesians descended from kinship groups in south-east Asia discovered new islands in the Pacific in the Holocene period, up to 5000 calendar years before the present day. The European voyages of discovery in the Pacific from the eighteenth century, in the Anthropocene era, brought Polynesian and European cultures together, resulting in exchanges that threw their cross-cultural differences into relief. As Bernard Smith suggests: “The scientific examination of the Pacific, by its very nature, depended on the level reached by the art of navigation” (Smith 1985:2). Two very different cultural systems, with different navigational practices, began to interact. 1 The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 49 Their varied cultural ontologies were based on different views of society, science, religion, history, narrative, and beliefs about the world. -

French Polynesia

ConContents tin uum Com plete In ter na tion al En cy clo pe dia of Sexuality • THE • CONTINUUM Complete International ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SEXUALITY • ON THE WEB AT THE KINSEY IN STI TUTE • https://kinseyinstitute.org/collections/archival/ccies.php RAYMOND J. NOONAN, PH.D., CCIES WEBSITE EDITOR En cyc lo ped ia Content Copyr ight © 2004-2006 Con tin uum In ter na tion al Pub lish ing Group. Rep rinted under license to The Kinsey Insti tute. This Ency c lope dia has been made availa ble on line by a joint effort bet ween the Ed itors, The Kinsey Insti tute, and Con tin uum In ter na tion al Pub lish ing Group. This docu ment was downloaded from CCIES at The Kinsey In sti tute, hosted by The Kinsey Insti tute for Research in Sex, Gen der, and Rep ro duction, Inc. Bloomington, In di ana 47405. Users of this website may use downloaded content for non-com mercial ed u ca tion or re search use only. All other rights reserved, includ ing the mirror ing of this website or the placing of any of its content in frames on outside websites. Except as previ ously noted, no part of this book may be repro duced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans mitted, in any form or by any means, elec tronic, mechan ic al, pho to copyi ng, re cord ing, or oth erw ise, with out the writt en per mis sion of the pub lish ers. Ed ited by: ROBER T T. -

Polynesia Dream -2

POLYNESIA DREAM -2- 11 days // 10 nights 2015 - 2016 Raiatea – Tahaa – Bora Bora – Huahine – Moorea – Tahiti DAY 1 RAIATEA // TAHAA SATURDAY Welcome and boarding at noon,. Downtown of Uturoa. Lunch and navigation inside Raiatea // Tahaa lagoon to Motu TauTau, water-based activities : snorkeling, in a coral garden, kayak rides DAY 2 RAIATEA SUNDAY Navigation to Bora Bora (4 hours). Lunch at anchor at the Motu Tapu. Afternoon : swimming with the reef sharks and discovery of one of the most beautiful lagoon in the South Pacific. Night at anchor in the East of Bora Bora. DAY 3 BORA BORA MONDAY Swimming with the manta rays. Breakfast and short navigation to the Motu Taurere. Beachcombing and kayaks rides. Option : Tahitian Barbecue lunch on a private motu. Afternoon of sailing in the famous lagoon of Bora Bora. Evening and night at Matira point. DAY 4 BORA BORA // RAIATEA TUESDAY After the breakfast, navigation of 4 hours to Raiatea island. Lunch at anchor, leisure afternoon : nautical activities, swimming, snorkelling. Option : Visit of a black pearl farm, snorkeling Evening and night at anchor. DAY 5 RAIATEA // TAHAA WEDNESDAY Stop at Raiatea for shopping in Uturoa, main village of Raiatea with the local market. Walk on the Tapioi Montain for a great overview.Option : guided tour of Raiatea, Taputapuatea temple, botanic, green valley and waterfalls. Short navigation to motu Cerant. Robinson day at anchor for water-based activities : kayak rides, beachcombing, bathing. DAY 6 HUAHINE THURSDAY Early departure to Huahine, navigation of 4 hours. Arrival in Bourayne Bay around noon. Afternoon, leisure activities at the beach of Ana Iti : kayaks, snorkeling parties, watersports. -

Kamay Botany Bay National Park Planning Considerations

NSW NATIONAL PARKS & WILDLIFE SERVICE Kamay Botany Bay National Park Planning Considerations environment.nsw.gov.au © 2020 State of NSW and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Department of Planning, Industry and Environment are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (DPIE) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. DPIE shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by DPIE and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. DPIE asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Department of Planning, Industry -

Atiu & Takutea

ATIU & TAKUTEA NEARSHORE MARINE ASSESSMENT 2019 © Ministry of Marine Resources (MMR) All rights for commercial reproduction and/or translation are reserved. The Cook Islands MMR authorises partial reproduction or translation of this work for fair use, scientific, educational/outreach and research purposes, provided MMR and the source document are properly acknowledged. Full reproduction may be permitted with consent of MMR management approval. Photographs contained in this document may not be reproduced or altered without written consent of the original photographer and/or MMR. Original Text: English Design and Layout: Ministry of Marine Resources Front Cover: Atiu Cliff and Goats Photo: Kirby Morejohn/MMR Inside Rear Cover: Takutea Birds Photo: Lara Ainley/MMR Rear Cover: The Grotto Photo: Kirby Morejohn/MMR Avarua, Rarotonga, Cook Islands, 2019 ATIU & TAKUTEA NEARSHORE MARINE ASSESSMENT Prepared for the Atiu Island Council and Community James Kora, Dr. Lara Ainley and Kirby Morejohn Ministry of Marine Resources This book is an abbreviated form of the 2018, Atiu and Takutea Nearshore Invertebrate and Finfish Assessment i TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Atiu ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 Takutea ............................................................................................................................................... -

POLYNESIA DREAM -1- 11 Days // 10 Nights 2015 - 2016 Tahiti – Moorea – Huahine – Raiatea – Bora Bora – Tahaa – Raiatea

POLYNESIA DREAM -1- 11 days // 10 nights 2015 - 2016 Tahiti – Moorea – Huahine – Raiatea – Bora Bora – Tahaa – Raiatea DAY 1 TAHITI WEDNESDAY Welcome and boarding at noon, Marina Taiana Papeete. Lunch aboard and sea crossing to Moorea island, 3 hours, Mooring in Vaiare Bay, front of the largest white sand beach of Moorea, night at anchor. DAY 2 MOOREA THURSDAY Navigation to Opunohu bay. Option : Halfday Safari excursion in Moorea with a guide : belvedere – the pineapple road - visit of archeological polynesian sites. Afternoon : Water-based activities, snorkeling at the Tiki spot, swimming with the sting rays. At the sunset, departure to Raiatea for a night navigation of 11 hours. DAY 3 RAIATEA FRIDAY Arrival for the breakfast in the South of Raiatea. Water-based activities : snorkelling parties – kayak rides – swimming. Afternoon, navigation inside the lagoon of Raiatea to Faaroa Bay, visit by dinghy of Faaroa river. Mooring and night front of a motu. DAY 4 RAIATEA // TAHAA SATURDAY Short navigation of 2 hours to Uturoa, main village of Raiatea. Shopping or walk on the Tapioi montain for a great overview. Panoramic lunch, short navigation inside the lagoon to Motu Tautau, at the North West of Tahaa. Water-based activities, swimming, kayak rides, beachcombing. DAY 5 TAHAA // BORA BORA SUNDAY Navigation to Bora Bora (4 hours). Lunch at anchor at the Motu Tapu. Afternoon : swimming with the reef sharks and discovery of one of the most beautiful lagoon in the South Pacific. Night at anchor in the East of Bora Bora. DAY 6 BORA BORA MONDAY Swimming with the manta rays. Breakfast and short navigation to the Motu Taurere. -

June Program Guide

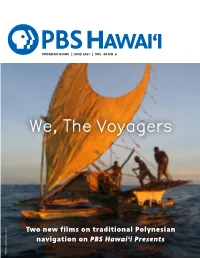

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

'Classification' of the Late Eighteenth Century Pacific

Empirical Power, Imperial Science: Science, Empire, and the ‘Classification’ of the Late Eighteenth Century Pacific A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Justin Wyatt Voogel Ó Copyright Justin Wyatt Voogel, September 2017 All Rights Reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History Arts and Science Admin Commons Room 522, Arts Building University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada i Abstract The Pacific of the mid eighteenth century was far removed from what it would become by the first decade of the nineteenth.