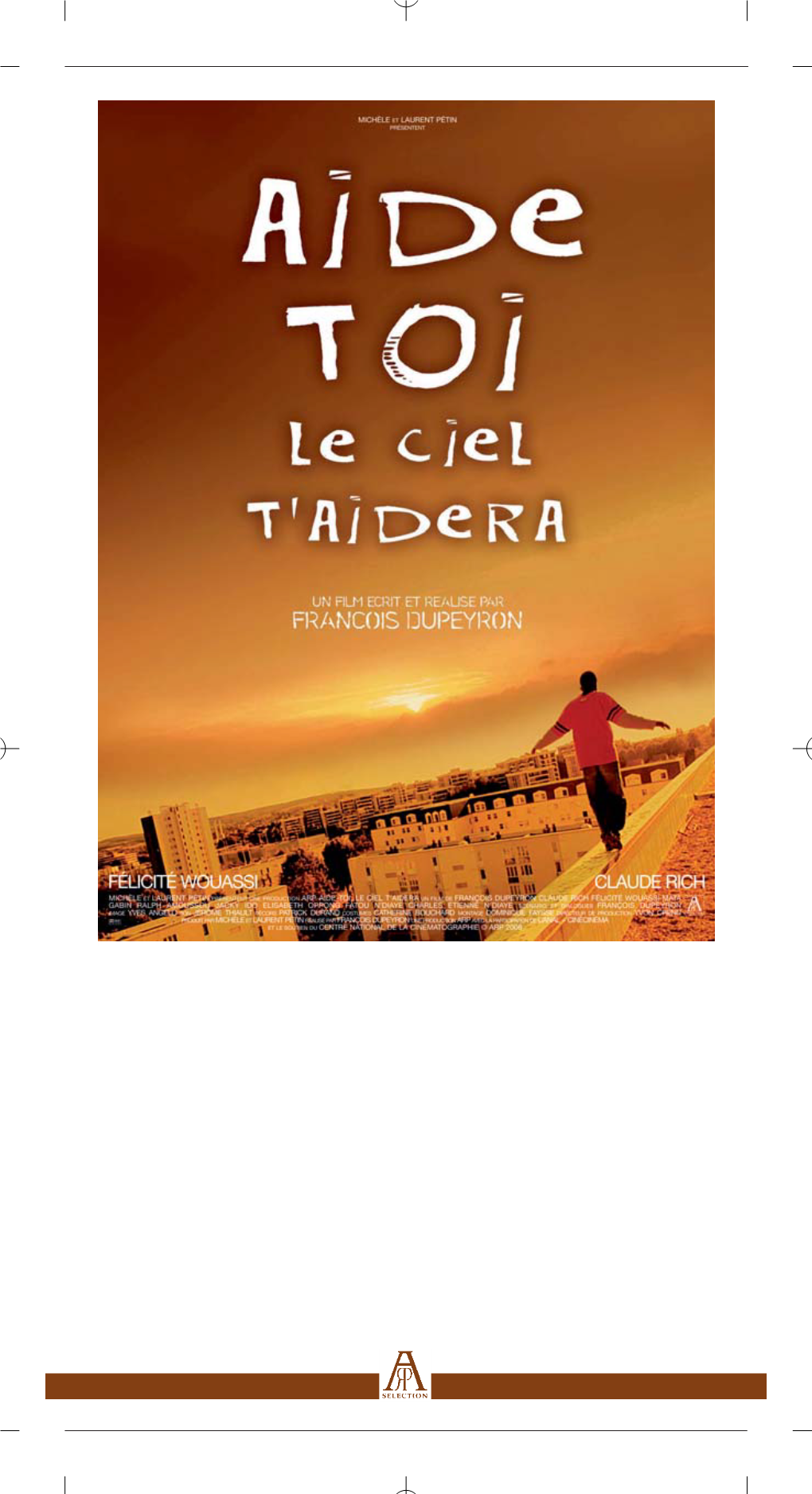

Aide Toi, Le Ciel T'aidera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE and BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release February 1994 JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND February 25 - March 18, 1994 A film retrospective of the legendary French actress Jeanne Moreau, spanning her remarkable forty-five year career, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on February 25, 1994. JEANNE MOREAU: NOUVELLE VAGUE AND BEYOND traces the actress's steady rise from the French cinema of the 1950s and international renown as muse and icon of the New Wave movement to the present. On view through March 18, the exhibition shows Moreau to be one of the few performing artists who both epitomize and transcend their eras by the originality of their work. The retrospective comprises thirty films, including three that Moreau directed. Two films in the series are United States premieres: The Old Woman Mho Wades in the Sea (1991, Laurent Heynemann), and her most recent film, A Foreign Field (1993, Charles Sturridge), in which Moreau stars with Lauren Bacall and Alec Guinness. Other highlights include The Queen Margot (1953, Jean Dreville), which has not been shown in the United States since its original release; the uncut version of Eva (1962, Joseph Losey); the rarely seen Mata Hari, Agent H 21 (1964, Jean-Louis Richard), and Joanna Francesa (1973, Carlos Diegues). Alternately playful, seductive, or somber, Moreau brought something truly modern to the screen -- a compelling but ultimately elusive persona. After perfecting her craft as a principal member of the Comedie Frangaise and the Theatre National Populaire, she appeared in such films as Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1957) and The Lovers (1958), the latter of which she created a scandal with her portrayal of an adultress. -

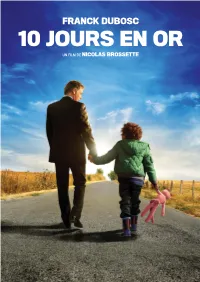

DP 10 Jours 02-11

FRANCK DUBOSC 10 JOURS EN OR UN FILM DE NICOLAS BROSSETTE • Objet promotionnel. Ne peut être vendu. TROÏKA Textes : Pascale & Gilles • Design Fabrication Maison / Textes Xavier DELMAS et Jean-Louis LIVI présentent un film de Nicolas BROSSETTE 10 JOURS EN OR avec FRANCK DUBOSC CLAUDE RICH MARIE KREMER Et pour la première fois à l'écran Mathis TOURÉ Produit par Jean-Louis LIVI et Xavier DELMAS Co-produit par Samuel HADIDA et Victor HADIDA Durée : 1h35 SORTIE LE 11 JANVIER 2012 Matériel presse disponible sur : http://presse.metropolitan-films.com www.10joursenor.fr DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT AS COMMUNICATION 29, rue Galilée - 75116 Paris PARTENARIATS & PROMOTION: Sandra Cornevaux & Karine de Haynin Tél. : 01 56 59 23 25 AGENCE CASABLANCA 11 bis, rue Magellan - 75008 Paris Fax : 01 53 57 84 02 Tél. : 01 47 01 39 90 Tél. : 01 47 23 00 02 [email protected] Fax : 01 47 01 07 32 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Marc Bajau sillonne le pays pour le compte d'une marque de vêtements. Il aime cette vie sur la route, libérée de toute contrainte et faite de rencontres d'un soir. Mais alors qu'il démarre une nouvelle tournée de promotion, sa dernière conquête s'en va en lui laissant son fils, Lucas, un petit métis de six ans… Commence alors une traversée de la France pas comme les autres, où Marc et Lucas vont croiser la route de Pierre, un retraité fantasque et envahissant, et celle de Julie, une jeune femme en errance. Au cours de cette odyssée, flanqué de son trio improbable, Marc Bajau va connaître « 10 jours en or » qui vont changer sa vie. -

Films in Competition and Parallel Sections

Marrakech Unveils Its Official Selection: Films in Competition and Parallel Sections • 14 films in Official Competition • 7 Moroccan films screened in the framework of a dedicated section • The 11th Continent, a new section to discover sharp and bold cinema • Gala screenings, Special Screenings, and general public screenings round out the programme Rabat, November 14, 2018, the Marrakech International Film Festival (FIFM) unveils the official selection. From November 30 to December 8, 2018, festival-goers and cinema-lovers alike will discover no fewer than 80 films coming from 29 different countries. The line-up is divided into several sections, the main ones including the Official Competition; Gala Screenings; Special Screenings; The 11th Continent; Moroccan Panorama; Jamaa El-Fna Square Screenings; Audio-described Cinema; and a Tribute section. Fourteen (14) films are thus in the running to win the Marrakech Etoile d’Or (or, the Gold Star), in the framework of the Official Competition of the 17th Edition of FIFM. In selecting these first or second feature-length films, the Festival grants priority to the discovery and consecration of new talents in world cinema. The selection is eclectic, its purpose being to showcase several cinematic universes developed in different regions of the world, with four (4) European films (from Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, and Serbia); three (3) films from Latin America (Argentina and Mexico); one (1) US film; two (2) Asian films (China and Japan); and four (4) films from the MENA region (Egypt, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia). Of the 14 films in competition, six are directed by women. Six great auteur films, with first-rate distribution, will be shown on the Festival’s gala evenings. -

Ricordi, Fortune E Rimpianti Del Capo Della Miramax, Che Ha Rinnovato Il

22 lunedì 4 marzo 2002 AMÉLIE NON SBANCA AGLI OSCAR FRANCESI, DELUSIONE PER MORETTI (E PER L’ITALIA) UN GALA PER RAFFAELLO LUCIANI Bocciato agli Oscar, «La stanza del figlio» di Nanni che aveva collezionato ben 13 nominations, si atten- Delusione, invece, per l'Italia e Nanni Moretti: l'ul- del defunto presidente della Repubblica Francois Lo scorso 23 dicembre è morto Moretti ha collezionato ieri sera un'altra delusione deva un trionfo e in molti prevedevano una decina timo italiano ad aggiudicarsi il César resta Roberto Mitterrand e responsabile del principale organismo Raffaello Luciani,editore di ai «César», i premi del cinema francese: «La stanza di statuette, sulle orme di «Cyrano de Bergerac» del Benigni, con «La vita è bella», nel 1999. Prima di di sovvenzione al cinema francese. Chiamato sul Danzasì, mensile di informazione del figlio» è stato battuto come miglior figlio stranie- 1991 e «L'ultimo metro» di Francois Truffaut, del lui, l'alloro francese aveva onorato l'Italia soltanto - palco a consegnare una statuetta, Frederic Mitter- della danza e promotore di ro da «Mulholland drive »di David Lynch. Niente 1981. Invece, al film sulla ragazzina di Montmar- e consecutivamente - nelle sue prime quattro edizio- rand ha criticato la politica italiana nel campo del innumerevoli iniziative per la danza. trionfo per il superfavorito «Il favoloso mondo di tre, oltre ai due premi principali sono andati solo ni: nel 1976, primo anno dei Cesar, vinse «Profumo cinema: «L'uomo che ha comprato l'Italia - ha Luciani e la sua «devozione» alla Amelie Poulain», che ha raccolto soltanto quattro quello per la miglior colonna sonora (Yann Tier- di donna» di Dino Risi; l'anno seguente, nel 1977, dichiarato - è anche quello che più ha contribuito a danza erano noti a tutti quelli che statuette. -

L'académie Des César Rend Hommage À Jean-Pierre

COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE Paris, le 25 avril 2019 L’ACADÉMIE DES CÉSAR REND HOMMAGE À JEAN-PIERRE MARIELLE Un monument du cinéma français vient de nous quitter. Cette carrure massive et ce franc-parler, au travers d’une voix chaude et grave, avaient fait de lui l’un des acteurs les plus populaires du cinéma français. Jean-Pierre Marielle était aussi et surtout un formidable interprète, qui incarnait ses rôles avec cet humour piquant et un certain cynisme qui lui étaient si propres. Jean-Pierre Marielle s’est retrouvé dès son plus Jeune âge parmi les futurs grands noms du cinéma, s’inscrivant lui-même au sein de cette incroyable génération : Jean-Paul Belmondo, Annie Girardot, Claude Rich, Françoise Fabian ou Jean Rochefort, font partie de ses camarades de classe au Conservatoire de Paris. Il se tourne tout d’abord vers le théâtre, avec un premier rôle dans une pièce de Molière, Le Mariage forcé, en 1953. Au cinéma, en 1964, il est aux côtés de Louis de Funès dans Faites sauter la banque de Jean Girault, et de Jean-Paul Belmondo dans Week-end à Zuydcoote d’Henri Verneuil. En 1969, il est auprès d’Yves Montand dans Le diable par la queue de Philippe de Broca. La décennie suivante le consacre comme un acteur incontournable des films populaires : Sex-shop de Claude Berri, La Valise de Georges Lautner, Comment réussir quand on est con et pleurnichard de Michel Audiard, Calmos de Bertrand Blier, Cause toujours… tu m’intéresses ! d’Edouard Molinaro, … Jean-Pierre Marielle ne cesse de tourner tandis que des rôles plus dramatiques s’offrent à lui, avec notamment Que la fête commence en 1975 et Coup de Torchon en 1981 de Bertrand Tavernier, Les Galettes de Pont-Aven de Joël Séria en 1975 pour lequel il est nommé pour le César du Meilleur Acteur lors de la toute première Cérémonie, Quelques jours avec moi de Claude Sautet en 1988, Uranus de Claude Berri ou encore l’inoubliable Tous les matins du monde réalisé par Alain Corneau en 1991, un rôle magnifique qui lui vaudra l’année suivante une nouvelle nomination pour le César du Meilleur Acteur. -

Films in Competition and Parallel Sections

Marrakech Unveils Its Official Selection: Films in Competition and Parallel Sections • 14 films in Official Competition • 7 Moroccan films screened in the framework of a dedicated section • The 11th Continent, a new section to discover sharp and bold cinema • Gala screenings, Special Screenings, and general public screenings round out the programme Rabat, November 14, 2018, the Marrakech International Film Festival (FIFM) unveils the official selection. From November 30 to December 8, 2018, festival-goers and cinema-lovers alike will discover no fewer than 80 films coming from 29 different countries. The line-up is divided into several sections, the main ones including the Official Competition; Gala Screenings; Special Screenings; The 11th Continent; Moroccan Panorama; Jamaa El-Fna Square Screenings; Audio-described Cinema; and a Tribute section. Fourteen (14) films are thus in the running to win the Marrakech Etoile d’Or (or, the Gold Star), in the framework of the Official Competition of the 17th Edition of FIFM. In selecting these first or second feature-length films, the Festival grants priority to the discovery and consecration of new talents in world cinema. The selection is eclectic, its purpose being to showcase several cinematic universes developed in different regions of the world, with four (4) European films (from Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, and Serbia); three (3) films from Latin America (Argentina and Mexico); one (1) US film; two (2) Asian films (China and Japan); and four (4) films from the MENA region (Egypt, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia). Of the 14 films in competition, six are directed by women. Six great auteur films, with first-rate distribution, will be shown on the Festival’s gala evenings. -

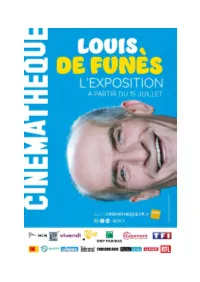

Exposition Louis De Funès

EXPOSITION LOUIS DE FUNÈS 15.07.20 ˃ 31.05.21 Véritable homme-orchestre, de Funès était mime, bruiteur, danseur, chanteur, pianiste, chorégraphe, en somme un créateur, un auteur à part entière. À travers plus de 300 œuvres, peintures, dessins et maquettes, documents, sculptures, costumes et, bien sûr, extraits de films (La Folie des grandeurs, Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob, La Grande Vadrouille, L’Aile ou la cuisse, la série des Gendarme…), l’exposition dévoile ainsi la diversité de son talent comique. EXPOSITION - FILMS - CONFÉRENCES - DISCUSSIONS - LECTURE - VISITES GUIDÉES - CATALOGUE… Alain Kruger, commissaire avec le concours de Thibaut Bruttin Serge Korber, conseiller du commissaire CONTACTS PRESSE LA CINÉMATHÈQUE FRANÇAISE Elodie Dufour [email protected] 01 71 19 33 65 / 06 86 83 65 00 Assistée d’Emmanuel Bolève [email protected] 01 71 19 33 49 2 SOMMAIRE 1- EXPOSITION ET CATALOGUE Du 15 juillet 2020 au 31 mai 2021 p4 Pile électrique et face atomique par Alain Kruger Au fil de l’exposition Catalogue Louis de Funès, à la folie Une coédition Éditions de La Martinière / La Cinémathèque française Visites guidées Les samedis et dimanches 18, 19, 25 et 26 juillet à 11h15 et 14h15. Puis, à partir de septembre : tous les samedis et dimanches à 11h15 Journées d’ateliers pour le jeune public Jeudi 16 juillet de 9h30 à 16h30 / Vendredi 17 juillet de 9h30 à 16h30 2- FILMS + DIALOGUES AVEC DANIÈLE THOMPSON p12 Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob Samedi 12septembre à 15h / Le Corniaud Dimanche 13 septembre à 14h30 3- CONFÉRENCES p13 « -

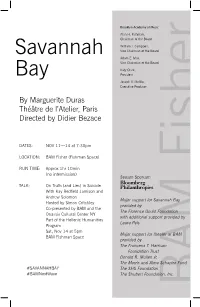

Savannah TALK: (No Intermission) Program

Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Savannah Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, Bay President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer By Marguerite Duras Théâtre de l’Atelier, Paris Directed by Didier Bezace DATES: NOV 11—14 at 7:30pm LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 10min (no intermission) Season Sponsor: TALK: On Truth (and Lies) in Suicide With Kay Redfield Jamison and Andrew Solomon Major support for Savannah Bay Hosted by Simon Critchley provided by Co-presented by BAM and the The Florence Gould Foundation Onassis Cultural Center NY with additional support provided by Part of the Hellenic Humanities Laura Pels Program Sat, Nov 14 at 5pm Major support for theater at BAM BAM Fishman Space provided by The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Donald R. Mullen Jr. The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund #SAVANNAHBAY The SHS Foundation #BAMNextWave The Shubert Foundation, Inc. BAM Fisher Savannah Bay ABOUT Savannah Bay NY Premiere DIRECTOR’S NOTE Two women in a pristine white room: The overarching subject of Savannah In French with English titles one young, one old. “Who was she?” Bay is the union of two women and one asks the other, referring to a third the role play in which they engage— DIRECTOR who had long ago met a boy, fallen in perhaps daily—to recognize one Didier Bezace love, and bore his child before drown- another. Stemming from a hidden and ing herself. buried traumatic event, which they ARTISTIC MANAGEMENT bring to the surface from a shred of Dyssia Loubatière Unfolding in the melancholic half- memory, they attempt to win each light of memory, Savannah Bay is a other over, to recognize and to love PERFORMERS mesmerizing two-character drama one another. -

![[Richard] Anderson ... [Christine] Whittaker Luc Chaput](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4736/richard-anderson-christine-whittaker-luc-chaput-1994736.webp)

[Richard] Anderson ... [Christine] Whittaker Luc Chaput

Document generated on 10/02/2021 1:46 a.m. Séquences : la revue de cinéma [Richard] Anderson ... [Christine] Whittaker Luc Chaput Pieds nus dans l’aube Number 311, December 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/87526ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Chaput, L. (2017). [Richard] Anderson ... [Christine] Whittaker. Séquences : la revue de cinéma, (311), 53–53. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ SALUT L'ARTISTE | 53 [Richard] Anderson ... [Christine] Whittaker Richard Anderson | 1926-2017 Novella Nelson | 1939-2017 Acteur américain spécialisé dans les rôles d’autorité dans les télé- Actrice et chanteuse noire américaine. Au théâtre à New York, séries de science-fiction Six Million Dollar Man et Bionic Woman. elle joua Clytemnestre dans Électre de Sophocle et tint un On le remarqua auparavant dans Paths of Glory de Kubrick. rôle important dans la comédie musicale Purlie. Elle fut aussi metteure en scène de pièces pour des compagnies de répertoire. Tom Alter | 1950-2017 Son rôle de la marâtre Mrs Tate dans Antwone Fisher de Denzel Acteur indien d’origine américaine. -

2020 IMG BAJ CARTE DE FUNES NEW CORR.Indd 1 07/04/20 09:52 *De Quel Film Est Tirée La Citation Suivante : « If I Go to the Turkish Bath, I Risk, I Risk Énormément

QUES TIONS INFO TEL PÈRE, TEL FILS Très complices, Louis de Funès et son fils Olivier ont tourné 6 films ensemble : Fantomas se déchaîne (1965), Le Grand Restaurant (1966), Les Grandes Vacances (1967), Hibernatus (1969), L’Homme-Orchestre (1970) et Sur un arbre perché (1971). En 1972, ils se donnent même la réplique sur scène dans la pièce de théâtre Oscar. 2020_IMG_BAJ_CARTE DE FUNES_NEW_CORR.indd 1 07/04/20 09:52 *De quel film est tirée la citation suivante : « If I go to the turkish bath, I risk, I risk énormément. » ? La Grande Vadrouille (1966) **Classez les films suivants, du plus récent au plus ancien : La Grande Vadrouille, Le Corniaud, La Soupe aux choux et Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob. La Soupe au choux (1981), Les Aventures de Rabbi Jacob (1973), La Grande Vadrouille (1966), Le Corniaud (1965) *Dans quel film Louis de Funès joue-t-il le rôle d’un chorégraphe autoritaire ? L’Homme-Orchestre (1970) **En quelle année Louis de Funès reçoit-il son César d’honneur : 1979, 1980 ou 1981 ? 1980 2020_IMG_BAJ_CARTE DE FUNES_NEW_CORR.indd 2 07/04/20 09:52 QUES TIONS INFO PREMIÈRE FOIS AU CINÉMA Au début de sa carrière, Louis de Funès enchaîne les petits rôles. En 1946, il apparaît pour la première fois dans La Tentation de Barbizon de Jean Stelli, où il interprète le portier du cabaret Le Paradis. Son apparition ne dure qu’une quarantaine de secondes. 2020_IMG_BAJ_CARTE DE FUNES_NEW_CORR.indd 3 07/04/20 09:52 *Dans quel film Louis de Funès donne-t-il la réplique à Coluche ? L’Aile ou la cuisse (1976) **Avec quelle célèbre actrice française, Louis de Funès partage-t-il l’affiche de La Zizanie (1978) ? Annie Girardot *À quel film doit-on la réplique suivante : « Y a quelqu’un ? Non y’a personne ! » ? Le Corniaud (1965) **Cherchez l’intrus : 1. -

Ambassade De France

CINEMA Rétrospective Moshé Mizrahi Du 25 juin au 28 août 2019 Cinémathèques de Tel Aviv, Jérusalem, Haïfa, Herzliya et Sderot Les cinémathèques de Tel Aviv, Jérusalem, Haïfa, Herzliya et Sderot rendent hommage au réalisateur et scénariste israélien Moshé Mizrahi décédé en août 2018 en proposant une rétrospective de ses films, pour certains dans une version restaurée, avec l’aide de TF1 Studio et le soutien de l’Institut français d’Israël. Moshé Mizrahi a réalisé une dizaine de films, en France et en Israël, dont certains, comme « La vie devant soi » (1978), film éponyme du roman de Romain Gary, Oscar du meilleur film en langue étrangère la même année, lui ont valu une reconnaissance internationale. A l’approche de l’anniversaire de sa mort, les cinémathèques de Tel Aviv, Jérusalem, Haïfa, Herzliya et Sderot ont souhaité lui rendre hommage en proposant une rétrospective de 13 de ses films : « Le Client de la morte saison » (1970), « Les stances à Sophie » (1971), « Rosa, je t’aime » (1972), « La maison de la rue Chelouche » (1973), inspirée largement de sa propre vie, « Les filles à papa » (1974), « La vie devant soi » (1977), « Chère inconnue » (1979), « Une jeunesse » (1983), « Everytime we say goodbye » (1986), « Mangeclous » (1988), « Warburg : un homme d’influence » (1992), « Femmes » (1996), Et « Week-end en Galilée » (2007), Moshé Mizrahi a fait tourner de grands noms du cinéma français, comme Bernadette Lafont, Claude Rich, Simone Signoret, Jean Rochefort, Jacques Dutronc, Pierre Richard, Jacques Villeret, ou Bernard Blier. Le pôle catalogue de TF1 Studio qui administre les droits cinémas de 1000 films dont certains de Moshé Mizrahi a naturellement voulu soutenir l’initiative des cinémathèques israéliennes en apportant son concours au processus de restauration de trois des films présentés – « Les Stances à Sophie », « Une jeunesse », « Le Client de la morte saison » – en coopération avec les Archives Israéliennes du Cinéma - Cinémathèque de Jérusalem. -

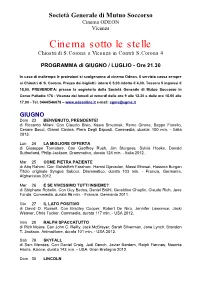

PROGRAMMA Di GIUGNO / LUGLIO - Ore 21.30

Società Generale di Mutuo Soccorso Cinema ODEON Vicenza Cinema sotto le stelle Chiostri di S.Corona a Vicenza in Contrà S.Corona 4 PROGRAMMA di GIUGNO / LUGLIO - Ore 21.30 In caso di maltempo le proiezioni si svolgeranno al cinema Odeon. Il servizio cassa sempre ai Chiostri di S. Corona. Prezzo dei biglietti: intero € 5,00 ridotto € 4,00. Tessera 5 ingressi € 18,00. PREVENDITA: presso la segreteria della Società Generale di Mutuo Soccorso in Corso Palladio 176 - Vicenza dal lunedì al venerdì dalle ore 9 alle 12.30 e dalle ore 15.00 alle 17.00 - Tel. 0444/546078 – www.odeonline.it e-mail: [email protected] GIUGNO Dom 23 BENVENUTO, PRESIDENTE! di Riccardo Milani. Con Claudio Bisio, Kasia Smutniak, Remo Girone, Beppe Fiorello, Cesare Bocci, Gianni Cavina, Piera Degli Esposti. Commedia, durata: 100 min. - Italia 2013. Lun 24 LA MIGLIORE OFFERTA di Giuseppe Tornatore. Con Geoffrey Rush, Jim Sturgess, Sylvia Hoeks, Donald Sutherland, Philip Jackson. Drammatico, durata 124 min. - Italia 2012. Mar 25 COME PIETRA PAZIENTE di Atiq Rahimi. Con Golshifteh Farahani, Hamid Djavadan, Massi Mrowat, Hassina Burgan Titolo originale Syngué Sabour. Drammatico, durata 103 min. - Francia, Germania, Afghanistan 2012. Mer 26 E SE VIVESSIMO TUTTI INSIEME? di Stéphane Robelin. Con Guy Bedos, Daniel Brühl, Geraldine Chaplin, Claude Rich, Jane Fonda. Commedia, durata 96 min. - Francia, Germania 2011. Gio 27 IL LATO POSITIVO di David O. Russell. Con Bradley Cooper, Robert De Niro, Jennifer Lawrence, Jacki Weaver, Chris Tucker. Commedia, durata 117 min. - USA 2012. Ven 28 RALPH SPACCATUTTO di Rich Moore. Con John C. Reilly, Jack McBrayer, Sarah Silverman, Jane Lynch, Brandon T.