There and It in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCCASIONAL PAPER #12 SYNTACTICIZATION of TOPIC N JAPANESE and MANDARIN STUDENTS' LISH: a TEST of RUTHERFORD's MODEL Patricia

OCCASIONAL PAPER #12 1985 SYNTACTICIZATION OF TOPIC N JAPANESE AND MANDARIN STUDENTS' LISH: A TEST OF RUTHERFORD'S MODEL Patricia Ann Duff DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AS A SECOND WGUAGE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT WOA occAsIoNAL PAPER SERIES In recent years, a number of graduate students in the Department of English as a Second Language have selected the thesis option as part of their Master of Arts degree progran. Their research has covered a wide range of areas in second language learning and teaching. Many of these studies have attracted interest from others in the fieldr and in order to make these theses more widely availabler selected titles are now published in the Occasional Paper Series. This series, a supplement to the departmental publication Workinq Papersr may also include reports of research by members of the ESL faculty. Publication of the Occasional Paper Series is underwritten by a grant from the Ruth Crymes Scholarship Fund. A list of available titles and prices may be obtained from the department and is also included in each issue of Workinq Papers. The reports published in the Occasional Paper Series have the status of n*progressreports nn, and may be published elsewhere in revised form. Occasional Faper #12 is an HA thesis by Patricia Ann Duff. Her thesis comm~ttee-members were Craig Chaudron (chair), Jean Gibsonr and Richard Schmidt. This work should be cited as follows: DUFFr Patricia Ann. 1985. Syntacticization of Topic in Japanese and Mandarin Students1 English: A Test of RutherfordnsModel. Occasional Paper #12. Honolulu: Department of English as a Second Languager mversity of Hawaii at Manoa* Rutherford (1983) drafted a two-part model to account for the syntacticization of Topic in the English of Japanese and Mandarin learners. -

Grammatical Sketch of Beng

Mandenkan Numéro 51 Bulletin d’études linguistiques mandé Printemps 2014 ISSN: 0752-5443 Grammatical sketch of Beng Denis PAPERNO University of Trento, Italy [email protected] Denis Paperno Content 1. Introduction 1 2. General information 9 2.1. Beng people and their language 9 2.2. Sociolinguistic situation 11 2.3. Names of the language 12 3. The history of Beng studies 12 3.1. Students of the Beng language and society 12 3.2. Beng dialects according to reports from the early 1900s 13 3.2.1. Delafosse: Beng of Kamélinsou 15 3.2.3. Tauxier: Beng of Groumania neighbourhood 16 4. Beng phonology 18 4.1. Phonological inventory 18 4.1.1. Tones 20 4.1.2. Syllable structure 22 4.1.3. Segmental sandhi 22 4.1.4. Tonal sandhi 22 4.2. Morphonology 23 4.2.1. ŋC simplification 23 4.2.2. Deletion of /l/ 24 4.2.3. High tone in the low tone form of verbs 24 5. Personal Pronoun Morphology 25 5.1. On the allomorphy of the 1SG subject pronoun 27 5.2. Contraction with 3SG object pronoun 28 5.3. Subject series of pronouns 29 5.4. Stative pronouns with verbs tá, nṵ̄ 29 6. Morphology of content words 30 6.1. Tonal changes in suffixation 31 6.1.1. Mobile tone suffixes 31 6.1.2. Low tone suffixes 31 6.1.3. Other suffixes 31 6.1.4. Stems ending in L tone 31 3 Denis Paperno 6.1.5. The verb blö ‘to press out’ 32 6.2. -

Download This Article

Grammatically Speaking by Michelle Jackson How to Teach the Dummy Pronoun “It” Sometimes the most interesting aspects of a language come in the smallest form. The English word it presents one of these fascinations. It can function as a typical pronoun. (E.g., I bought a new bike. It is blue.) In the example sentence, we use it to replace the noun bike. However, it can also function as an expletive or dummy pronoun. A dummy pronoun, unlike the pronoun in the example sentence above, does not replace a noun. It functions as a place holder to maintain the required subject, verb, object (SVO) structure. Some examples of it as a dummy pronoun occur when we describe weather (It is going to snow), distance (It is 2 miles to the metro station), time (It is 4 o’clock), or value judgments (It is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved as all). English has a robust use of the dummy pronoun because it is a nonpronoun dropping (non-pro- drop) language. We do not drop the pronoun in favor of maintaining the SVO structure. However, other pro-drop languages, such as Chinese, Turkish, Spanish, and Portuguese do not consistently require pronouns that can be inferred from contextual cues. Other null-subject languages that do not require a subject, such as Modern Greek and Arabic, do not require pronouns at all. Because the dummy pronoun does not necessarily occur in their mother tongues, students often fail to use it. Additionally, because the dummy pronoun carries no semantic information, it can pose a challenge to the instructor charged with its explanation. -

Bilingual Pronoun Resolution

Bilingual Pronoun Resolution: Experiments in English and French Cat˘ alina˘ Barbu A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2003 This work or any part thereof has not been presented in any form to the University or to any other body whether for purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless previously indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. Abstract Anaphora resolution has been a subject of research in computational linguistics for more than 25 years. The interest it aroused was due to the importance that anaphoric phenomena play in the coherence and cohesiveness of natural language. A deep understanding of a text is impossible without knowledge about how individual concepts relate to each other; a shallow understanding of a text is often impeded without resolving anaphoric phenomena. In the larger context of anaphora resolution, pronoun resolution has benefited from a wide interest, with pronominal anaphora being one of the most frequent discourse phenomena. The problem has been approached in a variety of manners, in various languages. The research presented in this thesis approaches the problem of pronoun resolution in the context of multilingual NLP applications. In the global information society we are living in, fast access to information in the language of one’s choice is essential, and this access is facilitated by emerging multilingual NLP applications. -

English for Practical Purposes 9

ENGLISH FOR PRACTICAL PURPOSES 9 CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction of English Grammar Chapter 2: Sentence Chapter 3: Noun Chapter 4: Verb Chapter 5: Pronoun Chapter 6: Adjective Chapter 7: Adverb Chapter 8: Preposition Chapter 9: Conjunction Chapter 10: Punctuation Chapter 11: Tenses Chapter 12: Voice Chapter 1 Introduction to English grammar English grammar is the body of rules that describe the structure of expressions in the English language. This includes the structure of words, phrases, clauses and sentences. There are historical, social, and regional variations of English. Divergences from the grammardescribed here occur in some dialects of English. This article describes a generalized present-dayStandard English, the form of speech found in types of public discourse including broadcasting,education, entertainment, government, and news reporting, including both formal and informal speech. There are certain differences in grammar between the standard forms of British English, American English and Australian English, although these are inconspicuous compared with the lexical andpronunciation differences. Word classes and phrases There are eight word classes, or parts of speech, that are distinguished in English: nouns, determiners, pronouns, verbs, adjectives,adverbs, prepositions, and conjunctions. (Determiners, traditionally classified along with adjectives, have not always been regarded as a separate part of speech.) Interjections are another word class, but these are not described here as they do not form part of theclause and sentence structure of the language. Nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs form open classes – word classes that readily accept new members, such as the nouncelebutante (a celebrity who frequents the fashion circles), similar relatively new words. The others are regarded as closed classes. -

Gaps and Dummies

Hans Bennis Gaps and Dummies 3a Amsterdam Academic Archive gaps and dummies The Amsterdam Academic Archive is an initiative of Amsterdam University Press. The series consists of scholarly titles which were no longer available, but which are still in demand in the Netherlands and abroad. Relevant sections of these publications can also be found in the repository of Amsterdam University Press: www.aup.nl/repository. At the back of this book there is a list of all the AAA titles published in 2005. Hans Bennis Gaps and Dummies 3a Amsterdam Academic Archive Gaps and Dummies was originally published as a PhD-dissertation in 1986 at the Katholieke Hogeschool Tilburg. It later appeared in the Linguistic Models-series from Foris Publications, Dordrecht (isbn 90 6765 245 8). Cover design: René Staelenberg, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 859 x nur 616 © Amsterdam University Press • Amsterdam Academic Archive, 2005 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. preface for the AAA-edition Gaps and Dummies was originally published as a PhD-dissertation in 1986 (defense May 1986). In addition to the dissertation version, it has appeared as a book in the series Lin- guistic Models, volume 9, with Foris Publications (second printing in 1987). Later, the series Linguistic Models has been taken over by Mouton de Gruyter (Berlin, New York). -

Latin Parts of Speech in Historical and Typological Context

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2014 Latin parts of speech in historical and typological context Viti, Carlotta Abstract: It is usually assumed that Latin parts of speech cannot be properly applied to other languages, especially outside the Indo-European domain. We will see, however, that the traditional distinction into eight parts of speech is established only in the late period of the classical school of grammar, while originally parts of speech varied in number and in type according to different grammarians, as well as to different periods and genres. Comparisons will be drawn on the one hand with parts of speech inthe Greek and Indian tradition, and on the other with genetically unrelated languages where parts of speech – notably adjectives and adverbs – are scarcely grammaticalized. This may be revealing of the manner in which the ancients used to categorize their language. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/joll-2014-0012 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-101955 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Viti, Carlotta (2014). Latin parts of speech in historical and typological context. Journal of Latin Linguistics, 13:279-301. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/joll-2014-0012 Journal of Latin Linguistics 2014; 13(2): 279 – 301 Carlotta Viti Latin parts of speech in historical and typological context Abstract: It is usually assumed that Latin parts of speech cannot be properly ap- plied to other languages, especially outside the Indo-European domain. -

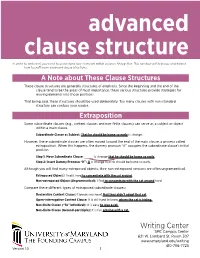

Writing Center SMC Campus Center 621 W

advanced clause structure In order to write well, you need to understand how elements within a clause fit together. This handout will help you understand how to craft more advanced clause structures. A Note about These Clause Structures These clause structures are generally structures of emphasis. Since the beginning and the end of the clause tend to be the areas of most importance, these various structures provide strategies for moving elements into those positions. That being said, these structures should be used deliberately. Too many clauses with non-standard structure can confuse your reader. Extraposition Some subordinate clauses (e.g., content clauses and non-finite clauses) can serve as a subject or object within a main clause. Subordinate Clause as Subject: That he should be home so early is strange. However, these subordinate clauses are often moved toward the end of the main clause, a process called extraposition. When this happens, the dummy pronoun “it” occupies the subordinate clause’s initial position. Step 1: Move Subordinate Clause: _____ is strange that he should be home so early. Step 2: Insert Dummy Pronoun “It”: It is strange that he should be home so early. Although you will find many extraposed objects, their non-extraposed versions are often ungramamtical. Extraposed Object: I find it hard to concentrate with the cat around. Non-extraposed Object (Ungrammatical): I find to concentrate with the cat around hard. Compare these different types of extraposed subordinate clauses: Declarative Content Clause: It breaks my heart that they didn’t adopt that cat. Open-interrogative Content Clause: It is still hard to know where the cat is hiding. -

The Pronoun in Tripartite Verbless Clauses in Biblical Hebrew: Resumption for Left-Dislocation Or Pronominal Copula?* Robert D. Holmstedt and Andrew R

To appear in the Journal of Semitic Studies, 2013 The Pronoun in Tripartite Verbless Clauses in Biblical Hebrew: Resumption for Left-Dislocation or Pronominal Copula?* Robert D. Holmstedt and Andrew R. Jones Abstract The status of the third person pronoun as a third element in verbless clauses has been a much studied issue in the history of biblical Hebrew syntax. As with most intriguing grammatical phenomena, scholarly opinion on this issue has shifted considerably over the last century or more. While the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed adherents to both copular and non- copular analyses for the ‘pleonastic’ pronoun in the so-called tripartite verbless clause, the second half of the twentieth century saw a consensus emerge, influenced particularly by the arguments of eminent scholars like Muraoka and Goldenberg: there was no pronominal copula in biblical Hebrew. In this paper we argue that this position does not adequately account for the data from linguistic typology or comparative Semitics and does not reflect a sensitive reading of the discourse context of many biblical examples. 1. Introduction Our purpose in this essay is to revisit a well-studied Hebrew grammatical phenomenon in order to nuance what has become the majority analysis. The specific phenomenon is the so-called tripartite verbless clause,1 that is, a clause lacking an overt verb as the predicate and consisting of three primary constituents, at least one of which is a third-person pronoun (henceforth, ‘PRON’), as in (1), given with two translations. (1) Gen 36:8 'עֵשָׂו הוּא אֱדוֹם a) ‘Esau is Edom’ (= copular analysis) b) ‘Esau, he is Edom’ (= dislocation analysis) For well over a century, the status of PRON in this clause type has been much debated. -

Chapter 4 the Cleft Pronoun and Cleft Clause

Chapter 4 The Cleft Pronoun and Cleft Clause This chapter focuses on the nature of the cleft pronoun and the cleft clause, and on the syntactic relation that holds between the four subcomponents of the cleft construction. It will be argued (1) that the cleft pronoun has referential status; (2) that the cleft clause is a relative clause; (3) that the cleft pronoun and the cleft clause function as a discontinuous constituent at the level serving as input to pragmatic interpretation; and (4) that the clefted constituent and the cleft clause form a syntactic constituent. I will suggest, finally, that all four of these requirements are satisfied by assuming a structure along the lines of (1) as the S-structure representation of the cleft construction: (1) IP it j I’ wask VP VP CPj t k NP whoi IP George t i won 4.1 The cleft pronoun Although most analysts consider the cleft subject pronoun to be an expletive, dummy pronoun which is a mere grammatical filler with no semantic content, this view has occasionally been challenged. Thus, Bolinger 1972b takes the position that the cleft pronoun has ‘low information but not vague reference,’ and Gundel 1977 proposes that the cleft pronoun makes ‘pronominal reference to the topic of the sentence.’ Borkin 1984 adopts the view that the initial it ‘suggests the already known existence of a referent,’ with the proviso that the intended referent is generally ‘clarified’ only in conjunction with the information expressed in the cleft clause. The purpose of this section is to present evidence in favor of the view that the cleft pronoun has semantic content. -

Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Impersonal, Missing Person And

lu Contents Abstract i Acknowledgements ii List of Tables .- xi list of Figures xii Abbreviations and Conventions xiii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 General Discussion on Complement Clauses 1 1.1.1 Complement Clauses Defined 1 1.1.2 Studies of Complement Clauses in English 2 1.1.3 Complement Theory: Cross-Linguistic Generalisations 7 1.1.4 Complementation in Finnish 9 1.2 Basic Outline of the Thesis 11 1.2.1 General Discussion 11 1.2.2 The Corpus 12 2 Impersonal, Missing Person and Existential Clause Types.. 14 2.1 Missing Person: Generic Third Person 14 2.2 Impersonal 17 2.3 Missing Person Versus Impersonal 19 2.4 Existential Clauses 21 2.4.1 Partitive 'Subject' 23 2.4.2 Partitive Ex-argument in Negation 23 2.4.3 Restriction on Pronominal Ex-argument 23 2.4.4 Indefinite Ex-argument 24 2.4.5 No Verb Agreement 24 2.4.6 Unmarked Constituent Order 24 2.4.7 Agentive Plural Ex-arguments may only be Partitive: Lack of Control... 25 2.4.8 Lackoflndividuation 26 2.4.9 No Adverbs 27 2.4.10 Existential Clause Expresses Typical Activity and Location 27 2.4.11 Usage of the Existential Clause in Discourse: Backgrounding 28 2.4.12 Restriction on Verbs 29 2.4.13 Existential Clauses and General Linguistic Theory 30 3 Grammatical Relations and Case Marking 31 3.1 Grammatical Case •. 31 3.1.1 The 'Accusative' Problem 31 3.1.2 Grammatical Relations 32 3.2 Subject 33 3.2.1 Morphological 'Coding Properties' of a Proto-typical Subject 33 3.2.2 The Syntactic 'Behavioural Properties' of the Proto-Typical Subject... -

Grammar Teaching Pronouns

Grammar Teaching Pronouns Definition: A pronoun replaces a noun – that is a name. Sometimes this is a proper noun, as in the name of a specific person, creature or place. E.g. ‘Joanna’ or ‘Mog’ (the cat) or ‘France’. Sometimes this is a common noun such as ‘table’, ‘lion’ or ‘village’. There are three types of pronoun 1. Personal pronouns 2. Possessive pronouns 3. Relative pronouns These refer to the (or determiners) These usually introduce missing name of a These refer to the a clause which gives us person, creature, place possession of someone more information about or thing. or something by a person, creature, place someone or something. or thing. Simon shouted to his mother. Mary is Sunil’s baby. The book, which was He shouted to her. She is his baby. unopened, lay on the windowsill. Peter loves Basanti. The cat has her pride. (‘which’ is a relative I love you. pronoun referring to the The blackbirds ate their book) Hobbes the dog loved to worms slowly. chase cats. Ann, who hated spiders, He loved to chase cats. All the old wooden climbed onto a chair. windows are Anna’s. (‘who’ - relative pronoun Lions like to sleep after All the old wooden referring to Ann) eating their prey. windows are hers. They like to sleep after (the windows belong to Goa is a place in India eating it. the Anna) that many people like to visit. The kitchen is a light, The bakery’s customers (‘that ‘ - relative pronoun airy room. were few but loyal. referring to Goa) It is a light, airy room.