Chapter 4 the Cleft Pronoun and Cleft Clause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Locative Constructions and Simple Clause Structures of English, Akan, and Safaliba

Basic Locative Constructions and Simple Clause Structures of English, Akan, and Safaliba Edward Owusu PhD Candidate, Department of Linguistics, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana, and Lecturer, Department of Liberal and General Studies, Sunyani Polytechnic, Sunyani, Ghana. John Agor, PhD Lecturer, Department of Linguistics, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana. AsuamahAdade-Yeboah PhD Candidate, UniveridadEmpresarial de Costa Rica (UNEM) Senior Lecturer, Department of Communication Studies, Christian Service University College, Kumasi, Ghana. Kofi Dovlo, PhD Senior Lecturer (Adjunct), Department of Linguistics, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana Abstract This paper discusses some basic locative constructions and simple clause structures of English, Akan (a majority language in Ghana), and Safaliba (a minority language in Ghana). Specifically, the paper compares the simple clause of and the basic locative constructions in these three languages by showing clearly how native speakers of these languages produce forms to express meaning. Structures such as clause functions, relative clause, verb forms, serial verb constructions, noun phrase, negation, and locative constructions have been employed as touchstones in juxtaposing the three languages. The data used,were drawn from native speakers’ intuition and expressions about the location of entities (this has been vividly explained in section 1.3). Several obversations were made. For example, it was realised that while English and Safaliba are pre- determiner languages, Akan is post-determiner language. Again as English recognises prepositions, Akan and Safaliba use postposition. Keywords: Basic locative constructions, Simple clause, Akan, Safaliba, Adpositional phrases 1. Introduction A sign, according to Saussure (1915/1966) is a combination of a concept and a sound-image, a combination that cannot be separated. -

OCCASIONAL PAPER #12 SYNTACTICIZATION of TOPIC N JAPANESE and MANDARIN STUDENTS' LISH: a TEST of RUTHERFORD's MODEL Patricia

OCCASIONAL PAPER #12 1985 SYNTACTICIZATION OF TOPIC N JAPANESE AND MANDARIN STUDENTS' LISH: A TEST OF RUTHERFORD'S MODEL Patricia Ann Duff DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AS A SECOND WGUAGE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT WOA occAsIoNAL PAPER SERIES In recent years, a number of graduate students in the Department of English as a Second Language have selected the thesis option as part of their Master of Arts degree progran. Their research has covered a wide range of areas in second language learning and teaching. Many of these studies have attracted interest from others in the fieldr and in order to make these theses more widely availabler selected titles are now published in the Occasional Paper Series. This series, a supplement to the departmental publication Workinq Papersr may also include reports of research by members of the ESL faculty. Publication of the Occasional Paper Series is underwritten by a grant from the Ruth Crymes Scholarship Fund. A list of available titles and prices may be obtained from the department and is also included in each issue of Workinq Papers. The reports published in the Occasional Paper Series have the status of n*progressreports nn, and may be published elsewhere in revised form. Occasional Faper #12 is an HA thesis by Patricia Ann Duff. Her thesis comm~ttee-members were Craig Chaudron (chair), Jean Gibsonr and Richard Schmidt. This work should be cited as follows: DUFFr Patricia Ann. 1985. Syntacticization of Topic in Japanese and Mandarin Students1 English: A Test of RutherfordnsModel. Occasional Paper #12. Honolulu: Department of English as a Second Languager mversity of Hawaii at Manoa* Rutherford (1983) drafted a two-part model to account for the syntacticization of Topic in the English of Japanese and Mandarin learners. -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

Adverb Phrases and Clauses Function in Specific Sentences

MS CCRS L.7.1a: Explain the function of Lesson 3 phrases and clauses in general and their Adverb Phrases and Clauses function in specific sentences. Introduction Phrases and clauses are groups of words that give specific information in a sentence. A clause has both a subject and a predicate, while a phrase does not. Some phrases and clauses function like adverbs, which means they modify a verb, an adjective, or another adverb in a sentence. • An adverb phrase tells “how,” “when,” “where,” or “why.” It is often a prepositional phrase. Soccer players wear protective gear on the field. (tells where; modifies verb wear) Soccer gloves are thick with padding. (tells how; modifies adjective thick) • An adverb clause can also tell “how,” “when,” “where,” or “why.” It is always a dependent clause. Gloves protect goalies when they catch the ball. (tells when; modifies verb protect) Goalies need gloves because the ball can hurt. (tells why; modifies verb need) Guided Practice Circle the word in each sentence that the underlined phrase or clause modifies. Write how, when, where, or why to explain what the phrase or clause tells. Hint 1 Goalies are the only players who touch the ball with their hands. Often an adverb phrase or clause immediately follows 2 As the ball comes toward the goal, the goalie moves quickly. the word it modifies, but sometimes other words separate the 3 If necessary, the goalie dives onto the ground. two. The phrase or clause may also come at the beginning of a 4 Sometimes the other team scores because the ball gets past sentence, before the the goalie. -

On the Position of Interrogative Phrases and the Order of Complementizer and Clause

On the position of interrogative phrases and the order of complementizer and clause Matthew S. Dryer Earlier versions of generative grammar, dating back to Bresnan (1970), proposed that wh-movement moves interrogative phrases into the position of complementizers. While the dominant view in generative grammar since Chomsky (1986) has been that wh-movement is movement into Spec of CP, the purpose of this paper is to examine typological evidence bearing on the earlier view, of movement into the position of complementizers. It investigates crosslinguistic patterns in the position of complementizers and the position of wh-phrases to determine whether there is any correlation between the two. While this does not appear to impact the more recent view of movement to Spec of CP, the patterns described here are of possible independent interest, both to generative linguists and to typologists.1 I argue that while the typological evidence initially appears to support the idea of a relationship between these two word order parameters, on more careful consideration, I conclude that there is no evidence of a correlation. Crosslinguistically, we find some languages which normally place wh-phrases at the beginning of sentences, as in English, while other languages normally leave such phrases in situ (Dryer 2011), as in (1) from Khwarshi (a Daghestanian language spoken in Russia).2 (1) Khwarshi (Khalilova 2009: 461) obut-t’-i uža-l hibo b-ez-i? father-OBL-ERG boy.OBL-LAT what III-buy-PAST.WITNESSED ‘What did the father buy his son?’ There is a third type of language that usually places wh-phrases at the beginning of sentences, though it is apparently optional. -

Clauses-And-Phrases-PUBLISHED-Fall-2017.Pdf

The Learning Hub Clauses & Phrases Writing Handout Series Grammar, Mechanics, & Style When constructing sentences, writers will use different building blocks of clauses and phrases to construct varied sentences. This handout will review how those phrases and clauses are constructed and where they can be placed in a sentence. Clauses Dependent Clauses A dependent clause has a subject and a verb but does not express a complete idea and cannot stand alone as a simple sentence. The two clauses below do not express a complete idea because of the subordinator at the beginning of the clause. Subordinators are words that commonly used to make independent clauses dependent clauses that help a writer connect ideas together and explain the relationship between clauses. Common subordinators like after, although, because, before, once, since, though, unless, until, when, where, and while come at the beginning of the clause. Subordinator Verb Since it is going to rain soon Subject Common Subordinators After Before Since When Although Even though Then Where As Even if Though Whether Because If Until While Independent Clauses An independent clause has a subject and a verb, expresses a complete idea, and is a complete sentence. The soccer game was cancelled Subject Verb Independent clauses are also referred to as simple sentences or complete sentences. Combining Clauses When combining independent and dependent clauses, there is a simple rule to remember. If the dependent clause comes before the independent clause, there must be a comma that separates the two clauses. If the dependent clause comes after the independent clause, then no comma is needed. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

Grammatical Sketch of Beng

Mandenkan Numéro 51 Bulletin d’études linguistiques mandé Printemps 2014 ISSN: 0752-5443 Grammatical sketch of Beng Denis PAPERNO University of Trento, Italy [email protected] Denis Paperno Content 1. Introduction 1 2. General information 9 2.1. Beng people and their language 9 2.2. Sociolinguistic situation 11 2.3. Names of the language 12 3. The history of Beng studies 12 3.1. Students of the Beng language and society 12 3.2. Beng dialects according to reports from the early 1900s 13 3.2.1. Delafosse: Beng of Kamélinsou 15 3.2.3. Tauxier: Beng of Groumania neighbourhood 16 4. Beng phonology 18 4.1. Phonological inventory 18 4.1.1. Tones 20 4.1.2. Syllable structure 22 4.1.3. Segmental sandhi 22 4.1.4. Tonal sandhi 22 4.2. Morphonology 23 4.2.1. ŋC simplification 23 4.2.2. Deletion of /l/ 24 4.2.3. High tone in the low tone form of verbs 24 5. Personal Pronoun Morphology 25 5.1. On the allomorphy of the 1SG subject pronoun 27 5.2. Contraction with 3SG object pronoun 28 5.3. Subject series of pronouns 29 5.4. Stative pronouns with verbs tá, nṵ̄ 29 6. Morphology of content words 30 6.1. Tonal changes in suffixation 31 6.1.1. Mobile tone suffixes 31 6.1.2. Low tone suffixes 31 6.1.3. Other suffixes 31 6.1.4. Stems ending in L tone 31 3 Denis Paperno 6.1.5. The verb blö ‘to press out’ 32 6.2. -

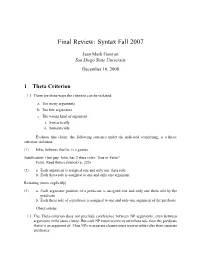

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 10, 2008 1 Theta Criterion 1.1 There are three ways the criterion can be violated: a. Too many arguments b. Too few arguments c. The wrong kind of argument i. Syntactically ii. Semantically Evaluate this claim: the following sentence under the indicated coindexing, is a theta- criterion violation. (1) Johni believes that hei is a genius. Justification: One guy, John, has 2 theta roles. True or False? False. Read theta-criterion (p. 225) (2) a. Each argument is assigned one and only one theta role. b. Each theta role is assigned to one and only one argument. Restating (more explicitly) (3) a. Each argument position of a predicate is assigned one and only one theta role.by the predicate b. Each theta role of a predicate is assigned to one and only one argument of the predicate. Observations: 1.1 The Theta-criterion does not preclude coreference between NP arguments, even between arguments in the same clause. But each NP must receive its own theta role from the predicate that it is an argument of. Thus NPs in separate clauses must receive tehta roles from separate predicates. 1.2 The theta criterion does preclude a predicate from assigning theta roles to NPs other than its OWN subject and complements. For example, a verb may not assign roles to NPs in another clause. 1.3 The theta criterion is not only about verbs. It is about ANY head and its complements and/or subject. (4) a. *Thebookofpoetryofprose b. -

Download This Article

Grammatically Speaking by Michelle Jackson How to Teach the Dummy Pronoun “It” Sometimes the most interesting aspects of a language come in the smallest form. The English word it presents one of these fascinations. It can function as a typical pronoun. (E.g., I bought a new bike. It is blue.) In the example sentence, we use it to replace the noun bike. However, it can also function as an expletive or dummy pronoun. A dummy pronoun, unlike the pronoun in the example sentence above, does not replace a noun. It functions as a place holder to maintain the required subject, verb, object (SVO) structure. Some examples of it as a dummy pronoun occur when we describe weather (It is going to snow), distance (It is 2 miles to the metro station), time (It is 4 o’clock), or value judgments (It is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved as all). English has a robust use of the dummy pronoun because it is a nonpronoun dropping (non-pro- drop) language. We do not drop the pronoun in favor of maintaining the SVO structure. However, other pro-drop languages, such as Chinese, Turkish, Spanish, and Portuguese do not consistently require pronouns that can be inferred from contextual cues. Other null-subject languages that do not require a subject, such as Modern Greek and Arabic, do not require pronouns at all. Because the dummy pronoun does not necessarily occur in their mother tongues, students often fail to use it. Additionally, because the dummy pronoun carries no semantic information, it can pose a challenge to the instructor charged with its explanation. -

Title on the CLEFT SENTENCE AND

ON THE CLEFT SENTENCE AND THE 'NOMINALIZED' Title SENTENCE IN IRISH Author(s) Nakamura, Chiye Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2004), 23: 47-62 Issue Date 2004-12-24 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/87845 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 23 (2004), 47-62 ON THE CLEFT SENTENCE AND THE ‘NOMINALIZED’ SENTENCE IN IRISH Chiye NAKAMURA I. Introduction The aim of this study is to show the difference between the cleft sentence and the sentence that is thought to be a quasi-cleft sentence, namely, `nominalized' sentence in Irish language. In the first part of this paper, their difference in Modern Irish will be shown. We will overview their historical development in the latter half of this paper. We encounter a number of cleft sentences used in prose texts in Modern Irish language. Many languages have 'clefting' as one of the pragmatic strategies, to make the focus element prominent. In Irish, the cleft sentence consists of [copula (is) +noun (underlined part) +relative clause (part in italics)] as illustrated in (1), which is a Modern Irish example: (1) Is a Sean a cheannaigh an leabhair. IS.pres. he Sean REL.PRT. buy.pret. the books 'It is Sean that bought the books .' We also notice the cleft sentence without the copula is at the head of the sentence used in prose texts in Irish language. The sentence consists of [noun (underlined part) +relative clause (italics part)] as illustrated in Modern Irish example (2): (2) Sean a cheannaigh an leabhair. Sean REL.PRT. buy.pret. -

Bilingual Pronoun Resolution

Bilingual Pronoun Resolution: Experiments in English and French Cat˘ alina˘ Barbu A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2003 This work or any part thereof has not been presented in any form to the University or to any other body whether for purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless previously indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. Abstract Anaphora resolution has been a subject of research in computational linguistics for more than 25 years. The interest it aroused was due to the importance that anaphoric phenomena play in the coherence and cohesiveness of natural language. A deep understanding of a text is impossible without knowledge about how individual concepts relate to each other; a shallow understanding of a text is often impeded without resolving anaphoric phenomena. In the larger context of anaphora resolution, pronoun resolution has benefited from a wide interest, with pronominal anaphora being one of the most frequent discourse phenomena. The problem has been approached in a variety of manners, in various languages. The research presented in this thesis approaches the problem of pronoun resolution in the context of multilingual NLP applications. In the global information society we are living in, fast access to information in the language of one’s choice is essential, and this access is facilitated by emerging multilingual NLP applications.