Complementizers, Faithfulness, and Optionality*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Locative Constructions and Simple Clause Structures of English, Akan, and Safaliba

Basic Locative Constructions and Simple Clause Structures of English, Akan, and Safaliba Edward Owusu PhD Candidate, Department of Linguistics, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana, and Lecturer, Department of Liberal and General Studies, Sunyani Polytechnic, Sunyani, Ghana. John Agor, PhD Lecturer, Department of Linguistics, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana. AsuamahAdade-Yeboah PhD Candidate, UniveridadEmpresarial de Costa Rica (UNEM) Senior Lecturer, Department of Communication Studies, Christian Service University College, Kumasi, Ghana. Kofi Dovlo, PhD Senior Lecturer (Adjunct), Department of Linguistics, University of Ghana, Legon, Accra, Ghana Abstract This paper discusses some basic locative constructions and simple clause structures of English, Akan (a majority language in Ghana), and Safaliba (a minority language in Ghana). Specifically, the paper compares the simple clause of and the basic locative constructions in these three languages by showing clearly how native speakers of these languages produce forms to express meaning. Structures such as clause functions, relative clause, verb forms, serial verb constructions, noun phrase, negation, and locative constructions have been employed as touchstones in juxtaposing the three languages. The data used,were drawn from native speakers’ intuition and expressions about the location of entities (this has been vividly explained in section 1.3). Several obversations were made. For example, it was realised that while English and Safaliba are pre- determiner languages, Akan is post-determiner language. Again as English recognises prepositions, Akan and Safaliba use postposition. Keywords: Basic locative constructions, Simple clause, Akan, Safaliba, Adpositional phrases 1. Introduction A sign, according to Saussure (1915/1966) is a combination of a concept and a sound-image, a combination that cannot be separated. -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

Adverb Phrases and Clauses Function in Specific Sentences

MS CCRS L.7.1a: Explain the function of Lesson 3 phrases and clauses in general and their Adverb Phrases and Clauses function in specific sentences. Introduction Phrases and clauses are groups of words that give specific information in a sentence. A clause has both a subject and a predicate, while a phrase does not. Some phrases and clauses function like adverbs, which means they modify a verb, an adjective, or another adverb in a sentence. • An adverb phrase tells “how,” “when,” “where,” or “why.” It is often a prepositional phrase. Soccer players wear protective gear on the field. (tells where; modifies verb wear) Soccer gloves are thick with padding. (tells how; modifies adjective thick) • An adverb clause can also tell “how,” “when,” “where,” or “why.” It is always a dependent clause. Gloves protect goalies when they catch the ball. (tells when; modifies verb protect) Goalies need gloves because the ball can hurt. (tells why; modifies verb need) Guided Practice Circle the word in each sentence that the underlined phrase or clause modifies. Write how, when, where, or why to explain what the phrase or clause tells. Hint 1 Goalies are the only players who touch the ball with their hands. Often an adverb phrase or clause immediately follows 2 As the ball comes toward the goal, the goalie moves quickly. the word it modifies, but sometimes other words separate the 3 If necessary, the goalie dives onto the ground. two. The phrase or clause may also come at the beginning of a 4 Sometimes the other team scores because the ball gets past sentence, before the the goalie. -

On the Position of Interrogative Phrases and the Order of Complementizer and Clause

On the position of interrogative phrases and the order of complementizer and clause Matthew S. Dryer Earlier versions of generative grammar, dating back to Bresnan (1970), proposed that wh-movement moves interrogative phrases into the position of complementizers. While the dominant view in generative grammar since Chomsky (1986) has been that wh-movement is movement into Spec of CP, the purpose of this paper is to examine typological evidence bearing on the earlier view, of movement into the position of complementizers. It investigates crosslinguistic patterns in the position of complementizers and the position of wh-phrases to determine whether there is any correlation between the two. While this does not appear to impact the more recent view of movement to Spec of CP, the patterns described here are of possible independent interest, both to generative linguists and to typologists.1 I argue that while the typological evidence initially appears to support the idea of a relationship between these two word order parameters, on more careful consideration, I conclude that there is no evidence of a correlation. Crosslinguistically, we find some languages which normally place wh-phrases at the beginning of sentences, as in English, while other languages normally leave such phrases in situ (Dryer 2011), as in (1) from Khwarshi (a Daghestanian language spoken in Russia).2 (1) Khwarshi (Khalilova 2009: 461) obut-t’-i uža-l hibo b-ez-i? father-OBL-ERG boy.OBL-LAT what III-buy-PAST.WITNESSED ‘What did the father buy his son?’ There is a third type of language that usually places wh-phrases at the beginning of sentences, though it is apparently optional. -

Clauses-And-Phrases-PUBLISHED-Fall-2017.Pdf

The Learning Hub Clauses & Phrases Writing Handout Series Grammar, Mechanics, & Style When constructing sentences, writers will use different building blocks of clauses and phrases to construct varied sentences. This handout will review how those phrases and clauses are constructed and where they can be placed in a sentence. Clauses Dependent Clauses A dependent clause has a subject and a verb but does not express a complete idea and cannot stand alone as a simple sentence. The two clauses below do not express a complete idea because of the subordinator at the beginning of the clause. Subordinators are words that commonly used to make independent clauses dependent clauses that help a writer connect ideas together and explain the relationship between clauses. Common subordinators like after, although, because, before, once, since, though, unless, until, when, where, and while come at the beginning of the clause. Subordinator Verb Since it is going to rain soon Subject Common Subordinators After Before Since When Although Even though Then Where As Even if Though Whether Because If Until While Independent Clauses An independent clause has a subject and a verb, expresses a complete idea, and is a complete sentence. The soccer game was cancelled Subject Verb Independent clauses are also referred to as simple sentences or complete sentences. Combining Clauses When combining independent and dependent clauses, there is a simple rule to remember. If the dependent clause comes before the independent clause, there must be a comma that separates the two clauses. If the dependent clause comes after the independent clause, then no comma is needed. -

Preposition Stranding Vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation

languages Article Preposition Stranding vs. Pied-Piping—The Role of Cognitive Complexity in Grammatical Variation Christine Günther Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Universität Siegen, 57076 Siegen, Germany; [email protected] Abstract: Grammatical variation has often been said to be determined by cognitive complexity. Whenever they have the choice between two variants, speakers will use that form that is associated with less processing effort on the hearer’s side. The majority of studies putting forth this or similar analyses of grammatical variation are based on corpus data. Analyzing preposition stranding vs. pied-piping in English, this paper sets out to put the processing-based hypotheses to the test. It focuses on discontinuous prepositional phrases as opposed to their continuous counterparts in an online and an offline experiment. While pied-piping, the variant with a continuous PP, facilitates reading at the wh-element in restrictive relative clauses, a stranded preposition facilitates reading at the right boundary of the relative clause. Stranding is the preferred option in the same contexts. The heterogenous results underline the need for research on grammatical variation from various perspectives. Keywords: grammatical variation; complexity; preposition stranding; discontinuous constituents Citation: Günther, Christine. 2021. Preposition Stranding vs. Pied- 1. Introduction Piping—The Role of Cognitive Grammatical variation refers to phenomena where speakers have the choice between Complexity in Grammatical Variation. two (or more) semantically equivalent structural options. Even in English, a language with Languages 6: 89. https://doi.org/ rather rigid word order, some constructions allow for variation, such as the position of a 10.3390/languages6020089 particle, the ordering of post-verbal constituents or the position of a preposition. -

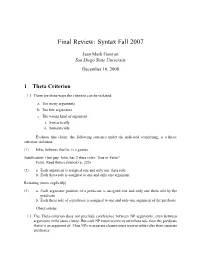

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007

Final Review: Syntax Fall 2007 Jean Mark Gawron San Diego State University December 10, 2008 1 Theta Criterion 1.1 There are three ways the criterion can be violated: a. Too many arguments b. Too few arguments c. The wrong kind of argument i. Syntactically ii. Semantically Evaluate this claim: the following sentence under the indicated coindexing, is a theta- criterion violation. (1) Johni believes that hei is a genius. Justification: One guy, John, has 2 theta roles. True or False? False. Read theta-criterion (p. 225) (2) a. Each argument is assigned one and only one theta role. b. Each theta role is assigned to one and only one argument. Restating (more explicitly) (3) a. Each argument position of a predicate is assigned one and only one theta role.by the predicate b. Each theta role of a predicate is assigned to one and only one argument of the predicate. Observations: 1.1 The Theta-criterion does not preclude coreference between NP arguments, even between arguments in the same clause. But each NP must receive its own theta role from the predicate that it is an argument of. Thus NPs in separate clauses must receive tehta roles from separate predicates. 1.2 The theta criterion does preclude a predicate from assigning theta roles to NPs other than its OWN subject and complements. For example, a verb may not assign roles to NPs in another clause. 1.3 The theta criterion is not only about verbs. It is about ANY head and its complements and/or subject. (4) a. *Thebookofpoetryofprose b. -

Lx522f08-10A-Cp.Pdf

Types of sentences • Sentences come in several types. We’ve mainly seen CAS LX 522 declarative clauses. Syntax I 1) Horton heard a Who. • But there are also questions (interrogative clauses)… Week 10a. 2) Did Horton hear a Who? CP & PRO 3) Who did Horton hear? (8.1-8.2.5) • …exclamatives… 4) What a crazy elephant! • …imperatives… 5) Pass me the salt. Declaratives & interrogatives Clause type • Our syntactic theory should allow us to distinguish between clause types. • Given this motivation, we seem to need one more category of lexical items, the clause • The basic content of Phil will bake a cake and Will Phil type category. bake a cake? is the same. • We’ll call this category C, which traditionally • Two DPs (Phil, nominative, and a cake, accusative), a stands for complementizer. modal (will), a transitive verb (bake) that assigns an The hypothesis is that a declarative sentence has Agent !-role and a Theme !-role. They are minimally • a declarative C in its structure, while an different: one’s an interrogative, and one’s a interrogative sentence (a question) has an declarative. One asserts that something is true, one interrogative C. requests a response about whether it is true. Embedding clauses What’s that ? • The reason for calling this element a complementizer stems from viewing the • We can show that that “belongs” to the embedded problem from a different starting point. sentence with constituency tests. 1) What I heard is that Lenny retired. • It is possible to embed a sentence within another sentence: 2) *What I heard that is Lenny retired. -

Constructions and Result: English Phrasal Verbs As Analysed in Construction Grammar

CONSTRUCTIONS AND RESULT: ENGLISH PHRASAL VERBS AS ANALYSED IN CONSTRUCTION GRAMMAR by ANNA L. OLSON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Linguistics, Analytical Stream We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Emma Pavey, PhD; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Sean Allison, Ph.D.; Second Reader ................................................................................ Dr. David Weber, Ph.D.; External Examiner TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY September 2013 © Anna L. Olson i Abstract This thesis explores the difference between separable and non-separable transitive English phrasal verbs, focusing on finding a reason for the non-separable verbs’ lack of compatibility with the word order alternation which is present with the separable phrasal verbs. The analysis is formed from a synthesis of ideas based on the work of Bolinger (1971) and Gorlach (2004). A simplified version of Cognitive Construction Grammar is used to analyse and categorize the phrasal verb constructions. The results indicate that separable and non-separable transitive English phrasal verbs are similar but different constructions with specific syntactic reasons for the incompatibility of the word order alternation with the non-separable verbs. ii Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 5 Syntax Summary of Sentence, Clause and Group Sentence Structure

Chapter 5 Syntax Summary of sentence, clause and group Sentence structure Proposition (Pp) – the structural name for the independent clause. Link – logical (Ll) – a coordinate or correlative conjunction etc. that connects two ic. dialogic (Ld) – a polar conjunction that serves as, or begins, a response to a question. Speaker’s Attitude (Sa) – an adverb or relative clause that comments on the independent clause. Topic (T) – a prepositional group that anticipates the Subject of the independent clause. Vocative (V) – a noun that calls, or addresses, the Subject of the independent clause. Tag Question (Q) – X/v + S/pn, or informal marker, that changes the speech function of the ic. False Start (F) – an incomplete Proposition prior to the Pp/ic. Hesitation Filler (H) – a verbalized hesitation before, or during, a Pp/ic. Feedback (D) – a word or sound, without semantic content, that indicates the decoder is listening. Discourse Marker (M) – a formulaic word that carries a boundary marking speech act etc. Clause class Independent clause (ic) – complete in itself as Pp/ic, includes a finite P/v. Relative clause (rc) – begins with a relative conjunction, and includes a finite P/v. Subordinate clause (sc) – begins with a subordinate conjunction, and includes a finite P/v. Non-finite clause (nfc) – includes, and often begins with, a non-finite P/vb. Alpha-beta clause complexes (ααββ) – two interdependent clauses; the beta begins with a beta conjunction Clause structure Subject (S) – the first participant in the nucleus realized by n, pn, ng (including ajg), rc, or nfc. Predicate (P) – the second event in the nucleus realized by v, vb, vg in ic, rc, sc, nfc Complement (Co/d/s/p/a) – the third positioned goal in nucleus realized by n, pn, aj, ajg, ng, pg, rc, nfc. -

Phrases-And-Clauses.Pdf

Phrases and Clauses A phrase is a group of two or more words, usually related in meaning, but with no subject/verb combination. As long as it is lacking both a subject and verb, a phrase cannot turn into a sentence, no matter what you might add to it. There are five types of phrases: • Prepositional - begins with a preposition, ends with a noun orpronoun that acts as the object of the preposition. Prepositional phrases can act like an adjective or adverb, but never a noun. When you are editing your writing, it’s a good idea to “read out” prepositional phrases from your sentences to make it easier to find the subject and the verb. Check here or in any handbook of English grammar for a list of prepositions: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_English_prepositions • Gerund - contains a present participle (ends in -ing) and acts like a noun. This means a gerund phrase can act as a subject of a clause or sentence, e.g., the teachings of some Buddhist schools focus on liberation from earthly existence; an object of a verb, e.g., if one eases suffering; or preposition, e.g., the secondary level of man’s thinking; or as a predicate noun (aka subjective completion) that completes the meaning of its preceding linking verb; e.g., happiness is knowing • Participial - contains a present, past or perfect participle (have, having, has or had + the past participle). Since it is a phrase, the subject is understood and the subject itself is named in the sentence for clarity, e.g., Having gone out their way to stop by the flower shop to pick up a bouquet for their hosts, Jackie and Ira were late for the dinner party. -

Adverb Clauses in Sentences | Grammar Worksheets

Name: ___________________________ Adverb Clauses in Sentences n adverb clause, like all clauses, has a verb and usually a subject. It is connected to the rest of the sentence with a subordinating conjunction, such as because , when , if , or although . Because Ait contains a subordinating conjunction, the adverb phrase is a dependent clause: it cannot stand alone as a complete sentence. It functions much as a single word adverb does: modifying a verb; adjective; or another adverb. However, an adverb clause may also modify an entire clause or phrase. It describes where, when, why, how, or how much something is happening. Example 1: Although it was late, Jane continued to read her book. The adverb clause is Although it was late . The subordinating conjunction is Although . The adverb clause tells when Jane was reading. Underline the adverb clause in each sentence below. Then, state if the sentence is complex or compound-complex. 1 . Because no one was home, the thieves robbed the house. 2 . If Perry calls, please tell him I am on my way, but I may be a bit late. 3 . Jose climbed the stairs after he finished his dinner; however, the 90 flights nearly killed him. 4 . We played on the beach until the sun set. 5 . You should visit the monument before you leave town. 6 . Farah was listening to music while she did her homework and studied for the test. 7 . On a cold day the dogs stayed in their kennel where it was warm but longed to play in the sun. 8 . Though it was not her job, Abby took out the trash.