FEZ1) in the Brain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Primate Specific Retrotransposons, Svas, in the Evolution of Networks That Alter Brain Function

Title: Primate specific retrotransposons, SVAs, in the evolution of networks that alter brain function. Olga Vasieva1*, Sultan Cetiner1, Abigail Savage2, Gerald G. Schumann3, Vivien J Bubb2, John P Quinn2*, 1 Institute of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZB, U.K 2 Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, Institute of Translational Medicine, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK 3 Division of Medical Biotechnology, Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, Langen, D-63225 Germany *. Corresponding author Olga Vasieva: Institute of Integrative Biology, Department of Comparative genomics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZB, [email protected] ; Tel: (+44) 151 795 4456; FAX:(+44) 151 795 4406 John Quinn: Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, Institute of Translational Medicine, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK, [email protected]; Tel: (+44) 151 794 5498. Key words: SVA, trans-mobilisation, behaviour, brain, evolution, psychiatric disorders 1 Abstract The hominid-specific non-LTR retrotransposon termed SINE–VNTR–Alu (SVA) is the youngest of the transposable elements in the human genome. The propagation of the most ancient SVA type A took place about 13.5 Myrs ago, and the youngest SVA types appeared in the human genome after the chimpanzee divergence. Functional enrichment analysis of genes associated with SVA insertions demonstrated their strong link to multiple ontological categories attributed to brain function and the disorders. SVA types that expanded their presence in the human genome at different stages of hominoid life history were also associated with progressively evolving behavioural features that indicated a potential impact of SVA propagation on a cognitive ability of a modern human. -

Psychosis: a Convergent Functional Genomics Approach Identifying a Series of Candidate Genes for Mania

Identifying a series of candidate genes for mania and psychosis: a convergent functional genomics approach ALEXANDER B. NICULESCU, III, DAVID S. SEGAL, RONALD KUCZENSKI, THOMAS BARRETT, RICHARD L. HAUGER and JOHN R. KELSOE Physiol. Genomics 4:83-91, 2000. You might find this additional information useful... This article cites 52 articles, 15 of which you can access free at: http://physiolgenomics.physiology.org/cgi/content/full/4/1/83#BIBL This article has been cited by 4 other HighWire hosted articles: Evaluation of common gene expression patterns in the rat nervous system S. Kaiser and L. K. Nisenbaum Physiol Genomics, December 16, 2003; 16 (1): 1-7. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] Microarray Technology: A Review of New Strategies to Discover Candidate Vulnerability Downloaded from Genes in Psychiatric Disorders W. E. Bunney, B. G. Bunney, M. P. Vawter, H. Tomita, J. Li, S. J. Evans, P. V. Choudary, R. M. Myers, E. G. Jones, S. J. Watson and H. Akil Am. J. Psychiatry, April 1, 2003; 160 (4): 657-666. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] Biomarker Identification by Feature Wrappers physiolgenomics.physiology.org M. Xiong, X. Fang and J. Zhao Genome Res., November 1, 2001; 11 (11): 1878-1887. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] GRK3 mediates desensitization of CRF1 receptors: a potential mechanism regulating stress adaptation F. M. Dautzenberg, S. Braun and R. L. Hauger Am J Physiol Regulatory Integrative Comp Physiol, April 1, 2001; 280 (4): R935-946. [Abstract] [Full Text] Medline items on this article's topics can be found at http://highwire.stanford.edu/lists/artbytopic.dtl on the following topics: on August 11, 2005 Immunology . -

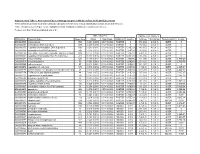

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

Convergent Functional Genomics of Schizophrenia: from Comprehensive Understanding to Genetic Risk Prediction

Molecular Psychiatry (2012) 17, 887 -- 905 & 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/12 www.nature.com/mp IMMEDIATE COMMUNICATION Convergent functional genomics of schizophrenia: from comprehensive understanding to genetic risk prediction M Ayalew1,2,9, H Le-Niculescu1,9, DF Levey1, N Jain1, B Changala1, SD Patel1, E Winiger1, A Breier1, A Shekhar1, R Amdur3, D Koller4, JI Nurnberger1, A Corvin5, M Geyer6, MT Tsuang6, D Salomon7, NJ Schork7, AH Fanous3, MC O’Donovan8 and AB Niculescu1,2 We have used a translational convergent functional genomics (CFG) approach to identify and prioritize genes involved in schizophrenia, by gene-level integration of genome-wide association study data with other genetic and gene expression studies in humans and animal models. Using this polyevidence scoring and pathway analyses, we identify top genes (DISC1, TCF4, MBP, MOBP, NCAM1, NRCAM, NDUFV2, RAB18, as well as ADCYAP1, BDNF, CNR1, COMT, DRD2, DTNBP1, GAD1, GRIA1, GRIN2B, HTR2A, NRG1, RELN, SNAP-25, TNIK), brain development, myelination, cell adhesion, glutamate receptor signaling, G-protein-- coupled receptor signaling and cAMP-mediated signaling as key to pathophysiology and as targets for therapeutic intervention. Overall, the data are consistent with a model of disrupted connectivity in schizophrenia, resulting from the effects of neurodevelopmental environmental stress on a background of genetic vulnerability. In addition, we show how the top candidate genes identified by CFG can be used to generate a genetic risk prediction score (GRPS) to aid schizophrenia diagnostics, with predictive ability in independent cohorts. The GRPS also differentiates classic age of onset schizophrenia from early onset and late-onset disease. -

W J B C Biological Chemistry

World Journal of W J B C Biological Chemistry Submit a Manuscript: https://www.f6publishing.com World J Biol Chem 2019 February 21; 10(2): 28-43 DOI: 10.4331/wjbc.v10.i2.28 ISSN 1949-8454 (online) REVIEW Fasciculation and elongation zeta proteins 1 and 2: From structural flexibility to functional diversity Mariana Bertini Teixeira, Marcos Rodrigo Alborghetti, Jörg Kobarg ORCID number: Mariana Bertini Mariana Bertini Teixeira, Jörg Kobarg, Institute of Biology, Department of Biochemistry and Teixeira (0000-0002-3431-3131); Tissue Biology, University of Campinas, Campinas 13083-862, Brazil Marcos Rodrigo Alborghetti (0000-0003-4517-5579); Jörg Kobarg Marcos Rodrigo Alborghetti, Department of Cell Biology, University of Brasilia, Brasilia (0000-0002-9419-0145). 70919-970, Brazil Author contributions: Teixeira MB, Jörg Kobarg, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Campinas, Campinas 13083- Alborghetti MR and Kobarg J 862, Brazil performed the literature search, analyses and interpretation of the Corresponding author: Jörg Kobarg, PhD, Full Professor, Molecular Biologist, Faculty of data; elaborated the figures; Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Campinas, Rua Monteiro Lobato 255, Bloco F, Sala conceived the overall idea of the 03, Campinas 13083-862, Brazil. [email protected] review, elaborated the final version Telephone: +55-19-35211443 of the text together; all the authors read, revised and approved the final version. Conflict-of-interest statement: The Abstract authors declare no conflict-of- Fasciculation and elongation zeta/zygin (FEZ) proteins are a family of hub interest. proteins and share many characteristics like high connectivity in interaction Open-Access: This article is an networks, they are involved in several cellular processes, evolve slowly and in open-access article which was general have intrinsically disordered regions. -

FEZ1) in the Brain

Review TheScientificWorldJOURNAL (2010) 10, 1646–1654 ISSN 1537-744X; DOI 10.1100/tsw.2010.151 Functions of Fasciculation and Elongation Protein Zeta-1 (FEZ1) in the Brain Andrés D. Maturana1,*, Toshitsugu Fujita2, and Shun’ichi Kuroda3,* 1Department of Bioengineering, Nagaoka University of Technology, Niigata, Japan; 2Research Institute for Microbial Diseases, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan; 3Graduate School of Bioagricultural Sciences, Nagoya University, Chikusa, Nagoya, Japan E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received March 16, 2010; Revised June 9, 2010; Accepted June 30, 2010; Published August 17, 2010 Fasciculation and elongation protein zeta-1 (FEZ1) is a mammalian ortholog of the Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-76 protein that possesses four coiled-coil domains and a nuclear localization signal. It is mainly expressed in the brain. Suppression of FEZ1 expression in cultured embryonic neurons causes deficiency of neuronal differentiation. Recently, proteomic techniques revealed that FEZ1 interacts with various intracellular partners, such as signaling, motor, and structural proteins. FEZ1 was shown to act as an antiviral factor. The findings reported so far indicate that FEZ1 is associated with neuronal development, neuropathologies, and viral infection. Based on these accumulating evidences, we herein review the biological functions of FEZ1. KEYWORDS: FEZ1, neuronal differentiation, neuronal disorders, virus infection, organelle transport DISCOVERY OF FASCICULATION AND ELONGATION PROTEIN ZETA-1 (FEZ1) FEZ1 is a mammalian ortholog of UNC-76, a protein found in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. UNC-76 has been used in an attempt to elucidate the mechanisms of locomotory defects. Genetic screenings of C. elegans mutants showing locomotory defects (uncoordinated or unc mutants) allowed the identification of various genes related to deficiencies in axonal guidance. -

A Study of Fez1 and Fez2

Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Pharmacy Molecular Cancer Research Group A study of Fez1 and Fez2 Establishment of Fez1 and Fez2 knock out cells lines Localization of Fez1 and Fez2 Jenny Thuy Tien Nguyen Acknowledgments This master thesis was carried out at the Molecular Cancer Research Group, Institute of Medical Biology, University of Tromsø – The artic University of Norway from August 2016 to May 2017. It has been a period of intense learning for me, not only in the scientific area, but also on a personal level. Therefore I would like to express my deepest thanks to the people who have supported and helped me throughout this period. I would first like to give my deepest thanks to my main supervisor associate-professor Eva Sjøttem, who has spent time to read my master thesis and has given me constructive feedback, and my lab-supervisor, Hanne Britt Brenne for always finding time to help when it was needed. They were both very generous with their time and knowledge and assisted me during the work with my thesis. Thank you both for your motivation, patience and encouragement. In addition, I would like to thank everyone who has given me some of their time and helped me during this master thesis. Last but not least, I must express my very profound gratitude to my family and friends. Thanks all for the encouragements and supports during my studies. This accomplishment would not have been possible without all of you. And special thanks to my mom, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study, I love you mom! Jenny Thuy Tien Nguyen Tromsø, May 2017 I II Abstract Autophagy is an essential cellular process that is important to maintain homeostasis by degrading proteins, lipids and organelles during critical times like cellular or environmental stress conditions. -

Phosphorylation-Regulated Axonal Dependent Transport of Syntaxin 1 Is Mediated by a Kinesin-1 Adapter

Phosphorylation-regulated axonal dependent transport of syntaxin 1 is mediated by a Kinesin-1 adapter John Jia En Chuaa, Eugenia Butkevichb, Josephine M. Worseckc, Maike Kittelmannd, Mads Grønborga, Elmar Behrmanna, Ulrich Stelzlc, Nathan J. Pavlosa, Maciej M. Lalowskie,1, Stefan Eimerd, Erich E. Wankere, Dieter Robert Klopfensteinb,f,2, and Reinhard Jahna,2 aDepartment of Neurobiology, Max-Planck-Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; bGeorg-August-Universität Göttingen, Drittes Physikalisches Institut-Biophysik, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; fBiochemistry II, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; cMax-Planck- Institute for Molecular Genetics, 14195 Berlin, Germany; dEuropean Neuroscience Institute Göttingen and German Research Foundation Research Center for Molecular Physiology of the Brain, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; and eMax Delbrueck Center for Molecular Medicine, 13092 Berlin-Buch, Germany Edited by Ronald D. Vale, University of California, San Francisco, CA, and approved March 5, 2012 (received for review August 22, 2011) Presynaptic nerve terminals are formed from preassembled vesicles knockouts (15), although in the latter case, a compensation by other that are delivered to the prospective synapse by kinesin-mediated Munc18 isoforms cannot be excluded. These defects were attrib- axonal transport. However, precisely how the various cargoes are uted to a need for Stx to be stabilized by Munc18 in the inactive linked to the motor proteins remains unclear. Here, we report conformation during transport to prevent it from being trapped in a transport complex linking syntaxin 1a (Stx) and Munc18, two pro- nonproductive SNARE complexes (10) but Munc18 could addi- teins functioning in synaptic vesicle exocytosis at the presynaptic tionally participate in loading Stx onto kinesin. -

Fez1/Lzts1 Alterations in Gastric Carcinoma1

1546 Vol. 7, 1546–1552, June 2001 Clinical Cancer Research Advances in Brief Fez1/Lzts1 Alterations in Gastric Carcinoma1 Andrea Vecchione,2 Hideshi Ishii,2 tected in one case that did not express Fez1/Lzts1. Hyper- Yih-Horng Shiao, Francesco Trapasso, methylation of the CpG island flanking the Fez1/Lzts1 pro- Massimo Rugge, Joseph F. Tamburrino, moter was evident in six of the eight cell lines examined as well as in the normal control. Yoshiki Murakumo, Hansjuerg Alder, 3 Conclusions: Our findings support FEZ1/LZTS1 as a Carlo M. Croce, and Raffaele Baffa candidate tumor suppressor gene at 8p in a subtype of Kimmel Cancer Center, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas gastric cancer and suggest that its inactivation is attributa- Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107 [A. V., H. I., F. T., J. F. T., Y. M., H. A., C. M. C., R. B.]; Laboratory of ble to several factors including genomic deletion and meth- Comparative Carcinogenesis, National Cancer Institute, Frederick ylation. Cancer Research and Development Center, NIH, Frederick, Maryland 21702 [Y-H. S.]; and Department of Pathology, University of Padova, Padova 35126, Italy [M. R.]. Introduction Gastric cancer is the second most common malignant tu- Abstract mor worldwide, with a much higher incidence in Asian than in 4 Purpose: Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) involving the Western countries (1). The international TNM classification (2) short arm of chromosome 8 (8p) is a common feature of the and Lauren’s system (3) classify gastric cancer into two distinct malignant progression of human tumors, including gastric histological types: intestinal (well differentiated) and diffuse cancer. -

Towards Personalized Medicine in Psychiatry: Focus on Suicide

TOWARDS PERSONALIZED MEDICINE IN PSYCHIATRY: FOCUS ON SUICIDE Daniel F. Levey Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Medical Neuroscience, Indiana University April 2017 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Andrew J. Saykin, Psy. D. - Chair ___________________________ Alan F. Breier, M.D. Doctoral Committee Gerry S. Oxford, Ph.D. December 13, 2016 Anantha Shekhar, M.D., Ph.D. Alexander B. Niculescu III, M.D., Ph.D. iii Dedication This work is dedicated to all those who suffer, whether their pain is physical or psychological. iv Acknowledgements The work I have done over the last several years would not have been possible without the contributions of many people. I first need to thank my terrific mentor and PI, Dr. Alexander Niculescu. He has continuously given me advice and opportunities over the years even as he has suffered through my many mistakes, and I greatly appreciate his patience. The incredible passion he brings to his work every single day has been inspirational. It has been an at times painful but often exhilarating 5 years. I need to thank Helen Le-Niculescu for being a wonderful colleague and mentor. I learned a lot about organization and presentation working alongside her, and her tireless work ethic was an excellent example for a new graduate student. I had the pleasure of working with a number of great people over the years. Mikias Ayalew showed me the ropes of the lab and began my understanding of the power of algorithms. -

Human Social Genomics in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

Getting “Under the Skin”: Human Social Genomics in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis by Kristen Monét Brown A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Epidemiological Science) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Ana V. Diez-Roux, Co-Chair, Drexel University Professor Sharon R. Kardia, Co-Chair Professor Bhramar Mukherjee Assistant Professor Belinda Needham Assistant Professor Jennifer A. Smith © Kristen Monét Brown, 2017 [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-9955-0568 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandmother, Gertrude Delores Hampton. Nanny, no one wanted to see me become “Dr. Brown” more than you. I know that you are standing over the bannister of heaven smiling and beaming with pride. I love you more than my words could ever fully express. ii Acknowledgements First, I give honor to God, who is the head of my life. Truly, without Him, none of this would be possible. Countless times throughout this doctoral journey I have relied my favorite scripture, “And we know that all things work together for good, to them that love God, to them who are called according to His purpose (Romans 8:28).” Secondly, I acknowledge my parents, James and Marilyn Brown. From an early age, you two instilled in me the value of education and have been my biggest cheerleaders throughout my entire life. I thank you for your unconditional love, encouragement, sacrifices, and support. I would not be here today without you. I truly thank God that out of the all of the people in the world that He could have chosen to be my parents, that He chose the two of you.