Meeting Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cabin Air Quality on Non-Smoking Commercial Flights: a Review of Published Data on Airborne Pollutants

CABIN AIR QUALITY ON NON-SMOKING COMMERCIAL FLIGHTS: A REVIEW OF PUBLISHED DATA ON AIRBORNE POLLUTANTS Ruiqing Chen1, Lei Fang2, Junjie Liu1, Britta Herbig3, Victor Norrefeldt4, Florian Mayer4, Richard Fox5 and Pawel Wargocki2* 1 Tianjin Key Laboratory of Indoor Air Environmental Quality Control, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Tianjin University, China 2 International Centre for Indoor Environment and Energy, Department of Civil Engineering, Technical University of Denmark 3 LMU University Hospital Munich, Institute and Clinic for Occupational, Social and Environmental Medicine, Germany 4 Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics IBP, Holzkirchen Branch, Germany 5 Aircraft Environment Solutions Inc., USA * Corresponding author: email [email protected] Abstract We reviewed 47 documents published 1967-2019 that reported measurements of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) on commercial aircraft. We compared the measurements with the air quality standards and guidelines for aircraft cabins and in some cases buildings. Average levels of VOCs for which limits exist were lower than the permissible levels except for benzene with average concentration at 5.9±5.5 μg/m3. Toluene, benzene, ethylbenzene, formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, limonene, nonanal, hexanal, decanal, octanal, acetic acid, acetone, ethanol, butanal, acrolein, isoprene and menthol were the most frequently appearing compounds. The concentrations of SVOCs (Semi-Volatile Organic Compounds) and other contaminants did not exceed standards and guidelines in buildings except for the average NO2 concentration at 12 ppb. Although the focus was on VOCs, we also retrieved the data on other parameters characterizing cabin environment. Ozone concentration averaged 38±30 ppb below the upper limit recommended for aircraft. The outdoor air supply rate ranged from 1.7 to 39.5 L/s per person and averaged 6.0±0.8 L/s/p (median 5.8 L/s/p), higher than the minimum level recommended for commercial aircraft. -

The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's) Derek Saunders

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 51 | Issue 1 Article 5 1985 The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's) Derek Saunders Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Derek Saunders, The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's), 51 J. Air L. & Com. 157 (1985) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol51/iss1/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE ANTITRUST IMPLICATIONS OF COMPUTER RESERVATIONS SYSTEMS (CRS's) DEREK SAUNDERS THE PASSAGE of the Airline Deregulation Act' dramat- ically altered the airline industry. Market forces, rather than government agencies, 2 began to regulate the indus- try. The transition, however, has not been an easy one. Procedures and relationships well suited to a regulated in- dustry are now viewed as outdated, onerous, and even anticompetitive. The current conflict over carrier-owned computer res- ervation systems (CRS's) represents one instance of these problems.3 The air transportation distribution system re- lies heavily on the use of CRS's, particularly since deregu- lation and the resulting increase in airline activity. 4 One I Pub. L. No. 95-504, 92 Stat. 1705 (codified at 49 U.S.C.A. § 1401 (Supp. 1984)). 2 Competitive Market Investigation, CAB Docket 36,595 (Dec. 16, 1982) at 3. For a discussion of deregulation in general and antitrust problems specifically, see Beane, The Antitrust Implications of Airline Deregulation, 45 J. -

Credit Travel Rewards Catalog Available, You Will Be Advised to Make an Alternate Selection Or May Return Your Points to Your Account

ScoreCard® Bonus Point Program Rules 4) Reservations shall also be subject to airline availability for advance gift shop purchases, gambling, beauty salon/barber shop/spa services, 1. As provided in these rules (“Rules”), account holders (“You” or “you”) earn (1) Point in the ScoreCard® fare category seating , non-refundable type tickets for the travel dates laundry, photographs, email, internet and fax, etc.) are the responsibility Program (“Program”) for every dollar in qualifying purchases that you: (i) charge to an eligible credit card specified. 5) ScoreCard travel services reserves the right to choose the of the Cardholder. 4) Cruises are non-refundable, non-cancelable and non- account covered by the Program (“Account”); and (ii) that appears on your statement during the Program Period. Purchases that are returned do not qualify for Points. No Points are earned for finance charges, fees, airline and routing on which to reserve and ticket Cardholders. transferable. Once redeemed, Bonus Points may not be added back to your cash advances, convenience checks, ATM withdrawals, foreign transaction currency conversion charges or ScoreCard account. 5) Please check with ScoreCard travel representatives Universal First Class/Business Class Ticket insurance charges posted to your account. Contact your financial institution (“Sponsor”) for full details on the Item Points Item # Item Points Item # for any documentation requirements or other restrictions associated Program Period dates during which you are eligible to earn Points. Cardholder is responsible for any overages above the maximum ticket with cruises. It is the guest’s responsibility to obtain appropriate 2. Points can be used to order the merchandise/travel awards (“Award(s)”) available in the current Program. -

Validating Carrier, Interline, and GSA

Validating Carrier, Interline, and GSA Developer Administration Guide August 2014 W Q2 © 2012-2014, Sabre Inc. All rights reserved. This documentation is the confidential and proprietary intellectual property of Sabre. Any unauthorized use, reproduction, preparation of derivative works, performance, or display of this document, or software represented by this document, without the express written permission of Sabre Inc. is strictly prohibited. Sabre and the Sabre logo design and Sabre Travel Network and the Sabre Travel Network logo design are trademarks and/or service marks of an affiliate of Sabre. All other trademarks, service marks, and trade names are owned by their respective companies. DOCUMENT REVISION INFORMATION The following information is to be included with all versions of the document. Project Project Name Number Prepared by Date Prepared Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. • • • Table of Contents 1 Getting Started 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Summary of Changes .................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 About This Guide ........................................................................................................................................... 1-2 2 -

Global Distribution Systems

Understanding the GDS Global Distribution Systems Presented by Kyle Kraft How airlines distribution works | Global Distribution Systems | New Distribution Capabilities (NDC) Produced by Altexsoft.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kysFEvbzEgA Video clip By AltexSoft, Inc REFERENCE: https://www.altexsoft.com/blog/travel/historyy-of-flight-booking-crss-gds-distribution-travel-agencies-and-online-reservations/ Quick Recap YouTube Video Est. 1987 Est. 1964 Est. 1997 Est. 1971-Apollo GDS – large flight aggregator collecting over 400 airlines inventory and distribute to travel agencies via their API (Application Programming Interface). GDS extended service offerings to include • Hotel, Rail, Cruise, Car Rental and Airport Transfers 3 Quick Recap YouTube Video How does the GDS work? Connects to the airline’s CRS (Central Reservation System) • CRS software manages the seat reservations on airline sites • Two additional 3rd Parties support GDS’ ATPCo – Airline Main global source of fare information is distributed across GDSs and OTA (Online Travel Agents) and Price Aggregators Innovata, OAG (Official Airline Guide)– provides scheduling services including flight schedules, routing and flight code information Quick Recap YouTube Video • Airlines lack of valuable customer data to enrich their ancillary and personalization offerings • Select seat, upgrade class of service, take additional luggage, secure priority boarding and order a better meal • Airlines working towards servicing directly with travelers – LF and low cost carrier Ryanair • IATA – -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

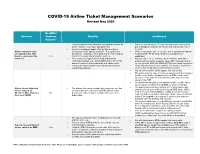

COVID-19 Airline Ticket Management Scenarios Revised May 2020

COVID-19 Airline Ticket Management Scenarios Revised May 2020 Do ARC’s Scenario Systems Benefits Challenges Support? • Ticket number is easily identified, stored and retrieved by • Tracking unused tickets: To track unused tickets, agents may airline, agency, corporation and passenger. pay a third party, maintain an internal tool or manually retrieve • Agency exchanges happen often so this scenario is the data. Airline maintains value already part of the agency workflow. The agency can • Airlines may not be able to extend e-ticket expiration (being able on original ticket. (The perform the exchange in their GDS and the ticketing data to maintain the ET for longer than their standard ticket ticket is considered the Yes is fed to their mid- and back-office systems. expiration). voucher.) • ARC’s systems support this method and allow for • Agency may need to exchange ticket manually. GDS auto- refunds/exchanges (e.g., ticket validity) up to 39 months pricing tool may not be available. Note: ARC understands that based on carrier e-ticket expiration and validity rules. as of early June 2020, the GDSs/ATPCO have made updates to • Tracing the end-to-end life of the transaction is simple allow auto-pricing tools to be utilized. This ability is dependent (old and new tickets). on the airline being able to extend ticket expiration. • Not all airlines and/or GDSs support this functionality. • The airline may not have a consistent way to notify the customer that the value has been transferred to an EMD, as the travel agency’s e-mail address (instead of the passenger’s) may be stored in the PNR • The airline-issued EMD is not reported to ARC, so ARC does not recognize the airline-issued EMD for future exchanges. -

MEDICAL GUIDELINES for AIRLINE TRAVEL 2Nd Edition

MEDICAL GUIDELINES FOR AIRLINE TRAVEL 2nd Edition Aerospace Medical Association Medical Guidelines Task Force Alexandria, VA VOLUME 74 NUMBER 5 Section II, Supplement MAY 2003 Medical Guidelines for Airline Travel, 2nd Edition A1 Introduction A1 Stresses of Flight A2 Medical Evaluation and Airline Special Services A2 Medical Evaluation A2 Airline Special Services A3 Inflight Medical Care A4 Reported Inflight Illness and Death A4 Immunization and Malaria Prophylaxis A5 Basic Immunizations A5 Supplemental Immunizations A5 Malaria Prophylaxis A6 Cardiovascular Disease A7 Deep Venous Thrombosis A8 Pulmonary Disease A10 Pregnancy and Air Travel A10 Maternal and Fetal Considerations A11 Travel and Children A11 Ear, Nose, and Throat A11 Ear A11 Nose and sinuses A12 Throat A12 Surgical Conditions A13 Neuropsychiatry A13 Neurological A13 Psychiatric A14 Miscellaneous Conditions B14 Air Sickness B14 Anemia A14 Decompression Illness A15 Diabetes A16 Jet Lag A17 Diarrhea A17 Fractures A18 Ophthalmological Conditions A18 Radiation A18 References Copyright 2003 by the Aerospace Medical Association, 320 S. Henry St., Alexandria, VA 22314-3579 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1984. Medical Guidelines for Airline Travel, 2nd ed. Aerospace Medical Association, Medical Guidelines Task Force, Alexandria, VA Introduction smoke, uncomfortable temperatures and low humidity, jet lag, and cramped seating (64). Nevertheless, healthy Each year approximately 1 billion people travel by air passengers endure these stresses which, for the most on the many domestic and international airlines. It has part, are quickly forgotten once the destination is been predicted that in the coming two decades, the reached. -

Procedure 20335E: Air Transportation

Controller’s Office Procedure Procedure 20335e: Air Transportation Rules and procedures for the purchase of air travel services, both on public carriers and charter aircraft are based on the requirement that all expenditures of the University must be necessary and reasonable and that the mechanism of payment must be in accordance with state and university procedures. A. Rates Public transportation rates must not exceed those for tourist/coach class accommodations. Business class or premium coach seating such as comfort plus air travel may be granted for international travel under the following circumstances: When the cost does not exceed the lowest available tourist/coach fare. For travel to Western Europe if the business meeting is conducted within three hours of landing. For transoceanic, intercontinental trips involving flight time of more than eight consecutive hours. If the traveler pays the difference. Business class for rail travel may be granted under the following circumstances: When it does not cost more than the lowest available tourist/coach fare (comparison must be attached to the travel reimbursement request). When reserved coach seats are not offered on the route. If the traveler pays the difference. Reimbursement for first class travel is prohibited. Travelers purchasing first class airline tickets will not be reimbursed for the expense from public funds. Travel Protection Insurance for airline tickets is not an allowable expense. Internet Purchases - Internet travel users must be careful when procuring airline tickets. The Internet sites often list only a class code and the user should know the following code designations: Tourist/Coach – B H K L Q T U V W Y Business Class – C J First Class – A D E F J P A.1 Fly America Act If international travel is being charged to a Federal grant or contract, then the “Fly America Act” applies. -

Boeing Environment Report 2017

THE BOEING COMPANY 2017 ENVIRONMENT REPORT BUILD SOMETHING CLEANER 1 ABOUT US Boeing begins its second century of business with a firm commitment to lead the aerospace industry into an environmentally progressive and sustainable future. Our centennial in 2016 marked 100 years of Meeting climate change and other challenges innovation in products and services that helped head-on requires a global approach. Boeing transform aviation and the world. The same works closely with government agencies, dedication is bringing ongoing innovation in more customers, stakeholders and research facilities efficient, cleaner products and operations for worldwide to develop solutions that help protect our employees, customers and communities the environment. around the globe. Our commitment to a cleaner, more sustainable Our strategy and actions reflect goals and future drives action at every level of the company. priorities that address the most critical environ- Every day, thousands of Boeing employees lead mental challenges facing our company, activities and projects that advance progress in customers and industry. Innovations that reducing emissions and conserving water and improve efficiency across our product lines resources. and throughout our operations drive reductions This report outlines the progress Boeing made in emissions and mitigate impacts on climate and challenges we encountered in 2016 toward change. our environmental goals and strategy. We’re reducing waste and water use in our In the face of rapidly changing business and facilities, even as we see our business growing. environmental landscapes, Boeing will pursue In addition, we’re finding alternatives to the innovation and leadership that will build a chemicals and hazardous materials in our brighter, more sustainable future for our products and operations, and we’re leading the employees, customers, communities and global development of sustainable aviation fuels. -

Dual RBD Implementation Guide

DYNAMIC PRICING Optimized Pricing via Dual RBD Validation Implementation Guide Version 3 August 2021 © 2021 ATPCO. All rights reserved. atpco.net Dual RBD Validation | Implementation Guide Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Overview of Dynamic Pricing Mechanisms ........................................................................................ 4 1.1. Simplified model for dynamic pricing ....................................................................................... 4 1.2. Which Dynamic Pricing solution is right for you? ..................................................................... 5 2. Dual RBD Validation .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.1. Problem Statement................................................................................................................. 6 2.2. Solution Overview .................................................................................................................. 7 2.3. Stakeholders and Impact Summary ........................................................................................ 8 Implementation Guide ........................................................................................................................... 9 3. Definitions ...................................................................................................................................... -

Medical Guidelines for Airline Passengers

MEDICAL GUIDELINES FOR AIRLINE PASSENGERS AEROSPACE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION ALEXANDRIA, VA (MAY, 2002) CONTRIBUTORS: Michael Bagshaw, M.D. James R. DeVoll, M.D. Richard T. Jennings, M.D. Brian F. McCrary, D.O. Susan E. Northrup, M.D. Russell B. Rayman, M.D. (Chair) Arleen Saenger, M.D. Claude Thibeault, M.D. 1 Introduction Approximately 1 billion people travel each year by air on the many domestic and international airlines. On U.S. air carriers alone, it has been predicted that in the coming two decades, the number of passengers will double. A global increase in air travel, as well as a growing aged population in many countries, makes it reasonable to assume that there will be a significant increase in older passengers and passengers with illness. Because of a growing interest by the public of health issues associated with commercial flying, the Aerospace Medical Association prepared this monograph for interested air travelers. It is informational only and should not be interpreted by the reader as prescriptive. If the traveler has any questions about fitness to fly, it is recommended that he or she consult a physician. The authors sincerely hope that this publication will educate the traveler and contribute to safe and comfortable flight for passengers. Stresses of Flight Modern commercial aircraft are very safe and, in most cases, reasonably comfortable. However, all flights, short and long haul, impose stresses on all passengers. Preflight, these include airport tumult (e.g., carrying baggage, walking long distances, and flight delays). Inflight stresses include lowered barometric and oxygen pressure, noise and vibration (including turbulence), cigarette smoking (banned on most airlines today), erratic temperatures, low humidity, jet lag, and cramped seating.