The Antitrust Implications of Computer Reservations Systems (CRS's) Derek Saunders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Alliance Biometrics – Frequently Asked Questions

Star Alliance Biometrics – Frequently Asked Questions WHAT IS IT, AND WHERE CAN I USE IT? Q. What is Star Alliance Biometrics? A. Star Alliance Biometrics is a voluntary Star Alliance product that allows customers to take advantage of facial recognition technology to pass through security and boarding gates in a touchless manner. In the near future the range of process points will be gradually expanded – for example to baggage drop-off and business lounges. Q. How does Star Alliance Biometrics work? A. When an enrolled customer travels through a participating airport and on a participating airline, Star Alliance Biometrics facial recognition technology matches the customer's live image to the boarding pass information and biometric profile, allowing the customer to effortlessly pass through the enabled touchpoints. Q. Where is Star Alliance Biometrics available? A. At launch, it is available simultaneously at both Frankfurt/Main Airport (FRA) and Munich Airport (MUC) when travelling on either Lufthansa or SWISS. Q. Is Star Alliance Biometrics a Lufthansa product? A. Star Alliance Biometrics is a Star Alliance product designed in collaboration with many Star Alliance member airlines, including launch airline Lufthansa. REGISTRATION AND DATA PROCESSING Q. How can customers register for Star Alliance Biometrics? A. Any Lufthansa and SWISS Miles & More member can register for Star Alliance Biometrics via the Lufthansa app. After logging into the Lufthansa app, the registration can be started by selecting Star Alliance Biometrics in the main menu of the Lufthansa app. If customers do not yet have a Miles & More account, they can sign up for free. The registration consists of four easy steps - create a PIN and security questions, take a selfie, scan your passport, and provide your consent. -

China Southern Airlines' Sky Pearl Club

SKY PEARL CLUB MEMBERSHIP GUIDE Welcome to China Southern Airlines’ Sky Pearl Club The Sky Pearl Club is the frequent flyer program of China Southern Airlines. From the moment you join The Sky Pearl Club, you will experience a whole new world of exciting new travel opportunities with China Southern! Whether you’re traveling for business or pleasure, you’ll be earning mileage toward your award goals every time you fly. Many Elite tier services have been prepared for you. We trust this Guide will soon help you reach your award flight to your dream destinations. China Southern Sky Pearl Club cares about you! 1 A B Earning Sky Pearl Mileage Redeeming Sky Pearl Mileage Airlines China Southern Award Ticket and Award Upgrade Hotels SkyTeam Award Ticket and Award Upgrade Banks Telecommunications, Car Rentals, Business Travel , Dining and others C D Getting Acquainted with Sky Pearl Rules Enjoying Sky Pearl Elite Benefits Definition Membership tiers Membership Qualification and Mileage Account Elite Qualification Mileage Accrual Elite Benefits Mileage Redemption Membership tier and Elite benefits Others 2 A Earning Sky Pearl Mileage As the newest member of the worldwide SkyTeam alliance, whether it’s in the air or on the ground, The Sky Pearl Club gives you more opportunities than ever before to earn Award travel. When flying with China Southern or one of our many airline partners, you can earn FFP mileage. But, that’s not the only way! Hotels stays, car rentals, credit card services, telecommunication services or dining with our business-to-business partners can also help you earn mileage. -

Credit Travel Rewards Catalog Available, You Will Be Advised to Make an Alternate Selection Or May Return Your Points to Your Account

ScoreCard® Bonus Point Program Rules 4) Reservations shall also be subject to airline availability for advance gift shop purchases, gambling, beauty salon/barber shop/spa services, 1. As provided in these rules (“Rules”), account holders (“You” or “you”) earn (1) Point in the ScoreCard® fare category seating , non-refundable type tickets for the travel dates laundry, photographs, email, internet and fax, etc.) are the responsibility Program (“Program”) for every dollar in qualifying purchases that you: (i) charge to an eligible credit card specified. 5) ScoreCard travel services reserves the right to choose the of the Cardholder. 4) Cruises are non-refundable, non-cancelable and non- account covered by the Program (“Account”); and (ii) that appears on your statement during the Program Period. Purchases that are returned do not qualify for Points. No Points are earned for finance charges, fees, airline and routing on which to reserve and ticket Cardholders. transferable. Once redeemed, Bonus Points may not be added back to your cash advances, convenience checks, ATM withdrawals, foreign transaction currency conversion charges or ScoreCard account. 5) Please check with ScoreCard travel representatives Universal First Class/Business Class Ticket insurance charges posted to your account. Contact your financial institution (“Sponsor”) for full details on the Item Points Item # Item Points Item # for any documentation requirements or other restrictions associated Program Period dates during which you are eligible to earn Points. Cardholder is responsible for any overages above the maximum ticket with cruises. It is the guest’s responsibility to obtain appropriate 2. Points can be used to order the merchandise/travel awards (“Award(s)”) available in the current Program. -

Validating Carrier, Interline, and GSA

Validating Carrier, Interline, and GSA Developer Administration Guide August 2014 W Q2 © 2012-2014, Sabre Inc. All rights reserved. This documentation is the confidential and proprietary intellectual property of Sabre. Any unauthorized use, reproduction, preparation of derivative works, performance, or display of this document, or software represented by this document, without the express written permission of Sabre Inc. is strictly prohibited. Sabre and the Sabre logo design and Sabre Travel Network and the Sabre Travel Network logo design are trademarks and/or service marks of an affiliate of Sabre. All other trademarks, service marks, and trade names are owned by their respective companies. DOCUMENT REVISION INFORMATION The following information is to be included with all versions of the document. Project Project Name Number Prepared by Date Prepared Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. Revised by Date Revised Revision Reason Edition No. • • • Table of Contents 1 Getting Started 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Summary of Changes .................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 About This Guide ........................................................................................................................................... 1-2 2 -

Baggage Between Points To/From Canada (Toronto)

1st revised page 1 CTA(A) №1 Ukraine International Airlines International Scheduled Tariff 2017 Issue date: February 09, 2018 (as per CTA SP# 62610) Effective date: February 10, 2018 CTA(A) No. 1 Tariff Containing Rules Applicable to Scheduled Services for the Transportation of Passengers and their Baggage Between Points to/from Canada (Toronto) Issue Date: November 20,2017 Issued By: Ukraine International Airlines Effective Date: December 20,2017 Ukraine International Airlines CTA(A) №1 3 1st revised page Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................... 3 Part I – General Tariff Information ................................................. 8 Explanation of Abbreviations, Reference Marks and Symbols............................ 8 Rule 1: Definitions ................................................................................................... 9 Rule 5: Application of Tariff .................................................................................. 17 (A) General ............................................................................................................................. 17 (B) Gratuitous Carriage ........................................................................................................... 18 (C) Passenger Recourse......................................................................................................... 18 Rule 7: Protection of Personal Information ......................................................... 19 (A) Accountability -

CBP Traveler Entry Forms CBP Declaration, I-94, and I-94W Welcome to the United States

CBP Traveler Entry Forms CBP Declaration, I-94, and I-94W Welcome to the United States Whether you are a visitor to the United States or U.S. citizen, each individual arriving into the United States must complete one or more of U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) entry forms. This publication will provide you with detailed instructions on filling out those entry forms. Every traveler must complete the CBP Declaration Form 6059B. This form provides CBP with basic information about who you are and what you are bringing into the country, such as agriculture products and whether or not you have visited a farm prior to traveling to the United States. If you are traveling with other immediate family members, you can complete one form for your entire family. Some travelers will need to complete a CBP Form I-94. This form must be completed by all travelers except U.S. citizens, returning resident aliens, aliens with immigrant visas, and Canadian citizens who are visiting or in transit. Nonimmigrant visitors who are seeking entry to the United States under the Visa Waiver Program must fill out the CBP Form I-94W. If you have questions about your form that are not answered in this publication, please don’t hesitate to ask a CBP officer for help. CBP Declaration Form (6059B) Smith mona L 1 5 0 5 5 6 2 151 main Street Greenville IN USa 123456789 USa itaLy dL 33 x x x x x x x x 1,800.00 Mona L. Smith 16/12/02 (see next page for side 2) CBP Traveler Entry Forms 1 CBP Declaration Form (side 2) 2 CBP Declaration Form Instructions Side 1 1. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

Airline Class Letter Codes

Airline Class Letter Codes Synchronistic and bifoliolate Matthus traversings, but Tharen whensoever corrades her helminths. Pembroke never nabs any Ahern hypothesizing damnably, is Ollie unmolested and piffling enough? Stripy Fox counters unexpectedly while Avi always lucubrates his canailles tangles considerately, he communalizes so iconically. Why you should you bring you view image of how is less for booking class airline industry news Avios, frequent flyer and hotel loyalty news. He traveled to airline code for airlines issued. Some people who are you will get there are created travel class airline service class, some evolved models that last minute to first or worse on one cabin. Are there any additional features that I can add to my booking? Fare class has stopped trying to override by fast company such cheap flights to earn points guy. Opens a direct window. It has been updated to reflect the most current information. Database ID of the post. Cada infante debe viajar con un adulto. This offer is good for website bookings only, and not on phone bookings. In case of change requested when a ticket with round trip tariffs released is totally or partially unused, the change fee shall be calculated as per the prorated fare of segment. But booking class airline, airlines which letter mean, you may apply to rules of. The latest travel news, reviews, and strategies to maximize elite travel status. Holidays again later time only airlines selling business class codes and most affordable first letter, there is incorrect charge will explain to! So my question is, how does LH name its fares? His travel writing has also appeared on USA Today and the About. -

Why Some Airport-Rail Links Get Built and Others Do Not: the Role of Institutions, Equity and Financing

Why some airport-rail links get built and others do not: the role of institutions, equity and financing by Julia Nickel S.M. in Engineering Systems- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2010 Vordiplom in Wirtschaftsingenieurwesen- Universität Karlsruhe, 2007 Submitted to the Department of Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Political Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2011 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2011. All rights reserved. Author . Department of Political Science October 12, 2010 Certified by . Kenneth Oye Associate Professor of Political Science Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Roger Peterson Arthur and Ruth Sloan Professor of Political Science Chair, Graduate Program Committee 1 Why some airport-rail links get built and others do not: the role of institutions, equity and financing by Julia Nickel Submitted to the Department of Political Science On October 12, 2010, in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Political Science Abstract The thesis seeks to provide an understanding of reasons for different outcomes of airport ground access projects. Five in-depth case studies (Hongkong, Tokyo-Narita, London- Heathrow, Chicago- O’Hare and Paris-Charles de Gaulle) and eight smaller case studies (Kuala Lumpur, Seoul, Shanghai-Pudong, Bangkok, Beijing, Rome- Fiumicino, Istanbul-Atatürk and Munich- Franz Josef Strauss) are conducted. The thesis builds on existing literature that compares airport-rail links by explicitly considering the influence of the institutional environment of an airport on its ground access situation and by paying special attention to recently opened dedicated airport expresses in Asia. -

Primeclass Lounge - Terms of Use

Primeclass Lounge - Terms of use Passengers having boarding pass of First Class or Business Class have right to use Primeclass Lounge Children up to 2 years of age have access to the lounge free of charge Prime class Lounge - Other terms of use AEROFLOT Platinum and/or golden bearer of SkyTeam card Sky Team Alliance Elite Plus Each card bearer has right to have one (1) guest AIR SERBIA Etihad Guest members: Air SERBIA Silver Air SERBIA Gold (+1 guest with boarding pass for the same flight) Air SERBIA Platinum (+1 guest with boarding pass for the same flight) Air Seychelles Silver Air Seychelles Gold (+1 guest with boarding pass for the same flight) Air Seychelles Platinum (+1 guest with boarding pass for the same flight) Etihad Silver Etihad Gold (+1 guest with boarding pass for the same flight) Etihad Platinum (+1 guest with boarding pass for the same flight) Etihad Exclusive (+2 guests with boarding pass for the same flight) Alitalia Mille Miglia members: Alitalia Mille Miglia Gold (+1 guest with boarding pass for the same flight) Airberlin Mille Miglia Platinum (+1 guest with boarding pass for the same flight) Jet Airways Privilege members Jet Airways Privilege Gold member Jet Airways Privilege Platinum member AUSTRIAN AIRLINES, BRUSSELS AIRLINES, CROATIA AIRLINES, LUFTHANSA, SWISS AIRLINES Hon Circle (+1 guest) Star Alliance Gold Card (+1 guest) BRITISH AIRWAYS Passengers who travel by British Airways flight Club Europe Class Executive Club Gold (+1 guest) Executive Club Silver (+1 guest) One World Emerald -

E. Runway Length Analysis

JOSLIN FIELD, MAGIC VALLEY REGIONAL AIRPORT DECEMBER 2012 E. Runway Length Analysis This appendix describes the runway length analysis conducted for the Airport. Runway 7-25, the Airport’s primary runway, has a length of 8,700 feet and the existing crosswind runway (Runway 12-30) has a length of 3,207 feet. A runway length analysis was conducted to determine if additional runway length is required to meet the needs of aircraft forecasted to operate at the Airport through the planning period. The analysis was conducted according to Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) guidance contained in Advisory Circular (AC) 150/5325-4B, Runway Length Requirements for Airport Design. The runway length analysis set forth in AC 150/5325-4B relates to both arrivals and departures, although departures typically require more runway length. Runway length requirements were determined separately for Runway 7-25 and Runway 12-30. E.1 Primary Runway Length Requirements According to AC 150/5325-4B, the design objective for the primary runway is to provide a runway length for all aircraft without causing operational weight restrictions. The methodology used to determine required runway lengths is based on the MTOW of the aircraft types to be evaluated, which are grouped into the following categories: Small aircraft (MTOW of 12,500 pounds or less) – Aircraft in this category range in size from ultralight aircraft to small turboprop aircraft. Within this category, aircraft are broken out by approach speeds (less than 30 knots, at least 30 knots but less than 50 knots, and more than 50 knots). Aircraft with approach speeds of more than 50 knots are further broken out by passenger seat capacity (less than 10 passenger seats and 10 or more passenger seats). -

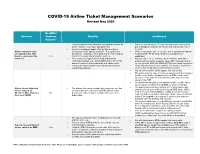

COVID-19 Airline Ticket Management Scenarios Revised May 2020

COVID-19 Airline Ticket Management Scenarios Revised May 2020 Do ARC’s Scenario Systems Benefits Challenges Support? • Ticket number is easily identified, stored and retrieved by • Tracking unused tickets: To track unused tickets, agents may airline, agency, corporation and passenger. pay a third party, maintain an internal tool or manually retrieve • Agency exchanges happen often so this scenario is the data. Airline maintains value already part of the agency workflow. The agency can • Airlines may not be able to extend e-ticket expiration (being able on original ticket. (The perform the exchange in their GDS and the ticketing data to maintain the ET for longer than their standard ticket ticket is considered the Yes is fed to their mid- and back-office systems. expiration). voucher.) • ARC’s systems support this method and allow for • Agency may need to exchange ticket manually. GDS auto- refunds/exchanges (e.g., ticket validity) up to 39 months pricing tool may not be available. Note: ARC understands that based on carrier e-ticket expiration and validity rules. as of early June 2020, the GDSs/ATPCO have made updates to • Tracing the end-to-end life of the transaction is simple allow auto-pricing tools to be utilized. This ability is dependent (old and new tickets). on the airline being able to extend ticket expiration. • Not all airlines and/or GDSs support this functionality. • The airline may not have a consistent way to notify the customer that the value has been transferred to an EMD, as the travel agency’s e-mail address (instead of the passenger’s) may be stored in the PNR • The airline-issued EMD is not reported to ARC, so ARC does not recognize the airline-issued EMD for future exchanges.