All the Way Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walter Heller Oral History Interview II, 12/21/71, by David G

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION LBJ Library 2313 Red River Street Austin, Texas 78705 http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/biopage.asp WALTER HELLER ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW II PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, Walter Heller Oral History Interview II, 12/21/71, by David G. McComb, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Compact Disc from the LBJ Library: Transcript, Walter Heller Oral History Interview II, 12/21/71, by David G. McComb, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. GENERAL SERVICES ADNINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY Legal Agreement Pertaining to the Oral History Interviews of Walter W. Heller In accordance with the provisions of Chapter 21 of Title 44, United States Code and subject to the terms and conditions hereinafter· set forth, I, Walter W. Heller of Minneapolis, Minnesota do hereby give, donate and convey to the United States of America all my rights, title and interest in the tape record- ings and transcripts of the personal interviews conducted on February 20, 1970 and December 21,1971 in Minneapolis, Minnesota and prepared for deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. This assignment is subject to the following terms and conditions: (1) The edited transcripts shall be available for use by researchers as soon as they have been deposited in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. (2) The tape recordings shall not be available to researchers. (3) During my lifetime I retain all copyright in the material given to the United States by the terms of this instrument. Thereafter the copyright in the edited transcripts shall pass to the United States Government. -

BERKELEY SUMMER SESSIONS the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr

Syllabus https://elearning.berkeley.edu/AngelUploads/Content/2013SUC... Printer Friendly Version BERKELEY SUMMER SESSIONS The Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr. (African American Studies 124, Summer Session 2013) about the course | materials | learning activities | grading | course policies | course outline About the Course Back to Top Course Description The life of Martin Luther King, Jr., provides a rare opportunity to understand the crucial issues of an era that shaped a good deal of contemporary America. As that era’s greatest leader, King’s life helps us both focus history and humanize it. As a profound thinker, as well as an activist, King epitomizes the interdependence of academic excellence and social responsibility. By examining the forces that shaped King’s life and his impact on society, we should gain some sense of history and historical possibility. By critically reviewing his political philosophy we should gain some appreciation of its depth and relevance for today. Recently, for example, protesters in Egypt were singing "We Shall Overcome." Each student will be expected to fully participate in the course including daily reading, watching the multimedia lecture presentations, engaging in interaction with the graduate student instructors and professor, posting short essays to a discussion board, interacting with peers in study sections, writing a critical book review of the Tyson book, taking four quizzes, and completing the mid-term and final examinations. Each quiz will count ten points. The mid-term and final examinations will count 20 points each and the critical book review will count 20 points. Extensions and incompletes will only be granted in rare circumstances. -

By Patrick James Barry a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The

CONFIRMATION BIAS: STAGED STORYTELLING IN SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARINGS by Patrick James Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Enoch Brater, Chair Associate Professor Martha Jones Professor Sidonie Smith Emeritus Professor James Boyd White TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY 1 CHAPTER 2 SITES OF STORYTELLING 32 CHAPTER 3 THE TAUNTING OF AMERICA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF ROBERT BORK 55 CHAPTER 4 POISON IN THE EAR: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF CLARENCE THOMAS 82 CHAPTER 5 THE WISE LATINA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF SONIA SOTOMAYOR 112 CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSION: CONFIRMATION CRITIQUE 141 WORK CITED 166 ii CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY The theater is a place where a nation thinks in public in front of itself. --Martin Esslin, An Anatomy of Drama (1977)1 The Supreme Court confirmation process—once a largely behind-the-scenes affair—has lately moved front-and-center onto the public stage. --Laurence Tribe, Advice and Consent (1992)2 I. In 1975 Milner Ball, then a law professor at the University of Georgia, published an article in the Stanford Law Review called “The Play’s the Thing: An Unscientific Reflection on Trials Under the Rubric of Theater.” In it, Ball argued that by looking at the actions that take place in a courtroom as a “type of theater,” we might better understand the nature of these actions and “thereby make a small contribution to an understanding of the role of law in our society.”3 At the time, Ball’s view that courtroom action had an important “theatrical quality”4 was a minority position, even a 1 Esslin, Martin. -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

Unwise and Untimely? (Publication of "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"), 1963

,, te!\1 ~~\\ ~ '"'l r'' ') • A Letter from Eight Alabama Clergymen ~ to Martin Luther J(ing Jr. and his reply to them on order and common sense, the law and ~.. · .. ,..., .. nonviolence • The following is the public statement directed to Martin My dear Fellow Clergymen, Luther King, Jr., by eight Alabama clergymen. While confined h ere in the Birmingham City Jail, I "We the ~ders igned clergymen are among those who, in January, 1ssued 'An Appeal for Law and Order and Com· came across your r ecent statement calling our present mon !)ense,' in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom, if ever, do We expressed understanding that honest convictions in I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts I sought to answer all of the criticisms that cross my but urged that decisions ot those courts should in the mean~ desk, my secretaries would he engaged in little else in time be peacefully obeyed. the course of the day, and I would have no time for "Since that time there had been some evidence of in constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of creased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Re genuine goodwill and your criticisms are sincerely set sponsible citizens have undertaken to work on various forth, I would like to answer your statement in what problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Bir I hope will he patient and reasonable terms. mingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and real I think I should give the reason for my being in Bir· istic approach to racial problems. -

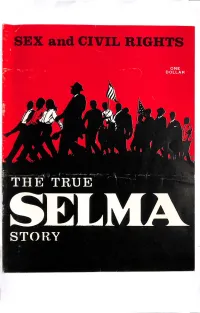

Martin Luther King and Communism Page 20 the Complete Files of a Communist Front Organization Were Taken in a Raid in New Orleans

Several hundred demonstrators were forced to stand on Dexter Ave1me in front of the State Capitol at Montgomery. On the night of March 10, 1965, these demonstrators, who knew that once they left the area they would not be able to return, urinated en masse in the street on the signal of James Forman, SNCC ExecJJtiVe Director. "All right," Forman shoute<)l, "Everyone stand up and relieve yourself." Almost everyone did. Some arrests were made of men who went to obscene extremes in expos ing themselves to local police officers. The True SELMA Story Albert C. (Buck) Persons has lived in Birmingham, Alabama for 15 years. As a stringer for LIFE and managing editor of a metropolitan weekly newspaper he covered the Birmingham demonstrations in 1963. On a special assignment for Con gressman William L. Dickinson of Ala bama he investigated the Selma-Mont gomery demonstrations in March, 1965. In 1961 Persons was one of a handful of pilots hired to support the invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. His story on this two years later led to the admission by President Kennedy that four Ameri can flyers had died in combat over the beaches of Southern Cuba in an effort to drive Fidel Castro from the armed Soviet garrison that had been set up 90 miles off the coast of the United States. After interviewing scores of people who were eye-witnesses to the Selma-Montgomery march, Mr. Persons has written the articles published here. In summation he says, "The greatest obstacle in the Negro's search for "freedom" is the Negro himself and the leaders he has chosen to follow. -

ANTHONY HILL, BLACK LIVES MATTER, and DSA by Adam Cardo

ANTHONY HILL, BLACK LIVES MATTER, AND DSA By Adam Cardo first became involved with DSA in the fall of 2014, as part of outside his apartment by DeKalb County Police officer Robert my larger political realignment brought on by the Black Lives Olson in March of 2015. Local activist groups who led the Matter movement. After spending the summer volunteering protest included Rise Up Georgia and #It’sBiggerThanYou, as for a moderate Democrat in Georgia, I began a semester at well as myself and several fellow Atlanta DSA members. We American University in Washington D.C., taking classes while also collected funds for the cause at our Socialist Dialogue. After interningI for another moderate Democrat. Fully enmeshed in an initial protest outside Hill’s neighborhood, activists focused mainstream “progressive” politics, I was all set to become a their efforts on securing an indictment of the accused officer neo-liberal Democratic Party apparatchik. However, two events with marches and rallies. The struggle culminated in a 3-day transpired to lead me camp-out outside the to the socialist light. DeKalb County The first was my courthouse during involvement with the the week of January Metro Washington 17th. The officer was D.C. DSA chapter, successfully indicted which I discovered on all six counts through a mutual against him. a c q u a i n t a n c e . The events The other crucial surrounding Anthony event was the non- Hill show the power indictment of the of Black Lives Matter police officers who in countering the murdered Eric Garner. -

Of Judicial Independence Tara L

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 2 Article 3 2018 The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence Tara L. Grove Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Tara L. Grove, The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence, 71 Vanderbilt Law Review 465 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol71/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence Tara Leigh Grove* The federal judiciary today takes certain things for granted. Political actors will not attempt to remove Article II judges outside the impeachment process; they will not obstruct federal court orders; and they will not tinker with the Supreme Court's size in order to pack it with like-minded Justices. And yet a closer look reveals that these "self- evident truths" of judicial independence are neither self-evident nor necessary implications of our constitutional text, structure, and history. This Article demonstrates that many government officials once viewed these court-curbing measures as not only constitutionally permissible but also desirable (and politically viable) methods of "checking" the judiciary. The Article tells the story of how political actors came to treat each measure as "out of bounds" and thus built what the Article calls "conventions of judicial independence." But implicit in this story is a cautionary tale about the fragility of judicial independence. -

A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1994 A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement Michelle Margaret Viera Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Viera, Michelle Margaret, "A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement" (1994). Master's Theses. 3834. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3834 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF FOUR KEY AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMALE FIGURES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Michelle Margaret Viera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My appreciation is extended to several special people; without their support this thesis could not have become a reality. First, I am most grateful to Dr. Henry Davis, chair of my thesis committee, for his encouragement and sus tained interest in my scholarship. Second, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. Benjamin Wilson and Dr. Bruce Haight, profes sors at Western Michigan University. I am deeply indebted to Alice Lamar, who spent tireless hours editing and re-typing to ensure this project was completed. -

MLK Resource Sheet

Created by Tonysha Taylor and Leah Grannum MLAC DEI 2021 Below you will find a complied list of resources, articles, events and more to honor the life and legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. The attempted coup at the Capitol on January 6th, 2021 was another reminder that we still have a lot of work to do to dismantle white supremacy. We hope you take this time to reflect, learn and remember Martin Luther King Jr. and his legacy- what he died for and what we continue to fight for. Resources and Virtual Events Teaching Black History and Culture: An Online Workshop for Educators. The workshop will be virtual (via Zoom) and combine a webinar, video and live streaming. Hosted by the Thomas D. Clark Foundation. Presented live from the Muhammad Ali Center. For more info and registration: https://nku.eventsair.com/ shcce/teaching/Site/Register Martin Luther King Jr. Day is a United States, holiday (third Monday in January) honoring the achievements of Martin Luther King, Jr. King’s birthday was finally approved as a federal holiday in 1983, and all 50 states A Call to Action: Then and Now: Dr. Martin Luther King, made it a state government holiday by 2000. Officially, King Jr. Celebration was born on January 15, 1929 in Atlanta. But the King holiday is marked every year on the third Monday in January. On January 18, 2021 at 3:45 p.m. EST the Madam Walker Legacy Center and Indiana University will Muhammad Ali Center MLK Day Celebration present "A Call to Action: Then and Now," a social justice virtual program with two of this nation's most prolific civil rights activists. -

The Senate in Transition Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Nuclear Option1

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYL\19-4\NYL402.txt unknown Seq: 1 3-JAN-17 6:55 THE SENATE IN TRANSITION OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE NUCLEAR OPTION1 William G. Dauster* The right of United States Senators to debate without limit—and thus to filibuster—has characterized much of the Senate’s history. The Reid Pre- cedent, Majority Leader Harry Reid’s November 21, 2013, change to a sim- ple majority to confirm nominations—sometimes called the “nuclear option”—dramatically altered that right. This article considers the Senate’s right to debate, Senators’ increasing abuse of the filibuster, how Senator Reid executed his change, and possible expansions of the Reid Precedent. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 632 R I. THE NATURE OF THE SENATE ........................ 633 R II. THE FOUNDERS’ SENATE ............................. 637 R III. THE CLOTURE RULE ................................. 639 R IV. FILIBUSTER ABUSE .................................. 641 R V. THE REID PRECEDENT ............................... 645 R VI. CHANGING PROCEDURE THROUGH PRECEDENT ......... 649 R VII. THE CONSTITUTIONAL OPTION ........................ 656 R VIII. POSSIBLE REACTIONS TO THE REID PRECEDENT ........ 658 R A. Republican Reaction ............................ 659 R B. Legislation ...................................... 661 R C. Supreme Court Nominations ..................... 670 R D. Discharging Committees of Nominations ......... 672 R E. Overruling Home-State Senators ................. 674 R F. Overruling the Minority Leader .................. 677 R G. Time To Debate ................................ 680 R CONCLUSION................................................ 680 R * Former Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy for U.S. Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid. The author has worked on U.S. Senate and White House staffs since 1986, including as Staff Director or Deputy Staff Director for the Committees on the Budget, Labor and Human Resources, and Finance. -

Intraparty in the US Congress.Pages

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2cd17764 Author Bloch Rubin, Ruth Frances Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ! ! ! ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! by! Ruth Frances !Bloch Rubin ! ! A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley ! Committee in charge: Professor Eric Schickler, Chair Professor Paul Pierson Professor Robert Van Houweling Professor Sean Farhang ! ! Fall 2014 ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress ! ! Copyright 2014 by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract ! Intraparty Organization in the U.S. Congress by Ruth Frances Bloch Rubin Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Eric Schickler, Chair The purpose of this dissertation is to supply a simple and synthetic theory to help us to understand the development and value of organized intraparty blocs. I will argue that lawmakers rely on these intraparty organizations to resolve several serious collective action and coordination problems that otherwise make it difficult for rank-and-file party members to successfully challenge their congressional leaders for control of policy outcomes. In the empirical chapters of this dissertation, I will show that intraparty organizations empower dissident lawmakers to resolve their collective action and coordination challenges by providing selective incentives to cooperative members, transforming public good policies into excludable accomplishments, and instituting rules and procedures to promote group decision-making.