“Creative Conservation:” the Environmental Legacy of Pres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyndon B. Johnson and the Great Society

LYNDON B. JOHNSON AND THE GREAT SOCIETY Books | Articles | Collections | Oral Histories | YouTube | Websites | Podcasts Visit our Library Catalog for a complete list of books, magazines and videos. Resource guides collate materials about subject areas from both the Museum’s library and permanent collections to aid students and researchers in resource discovery. The guides are created and maintained by the Museum’s librarian/archivist and are carefully selected to help users, unfamiliar with the collections, begin finding information about topics such as Dealey Plaza Eyewitnesses, Conspiracy Theories, the 1960 Presidential Election, Lee Harvey Oswald and Cuba to name a few. The guides are not comprehensive and researchers are encouraged to email [email protected] for additional research assistance. The following guide focuses on President Lyndon B. Johnson and his legislative initiative known as the Great Society, an ambitious plan for progressing the socio-economic well-being of American citizens. Inspired by President Kennedy’s policies, the Great Society enacted a series of domestic programs in education, the environment, civil rights, labor, the arts and health, all aimed toward eradicating poverty from American society. BOOKS Dallek, Robert. Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times 1961-73. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. Johnson, Lyndon B. The Vantage Point: Perspective of the Presidency 1963-1969. New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1971. Schenkkan, Robert. All the Way. New York: Grove Press, 2014. Schenkkan, Robert. The Great Society. New York: Grove Press, 2017. Woods, Randall Bennett. Prisoners of Hope: Lyndon B. Johnson, the Great Society, and the Limits of Liberalism. New York: Basic Books, 2016. -

Lady Bird Johnson STAAR 4, 7 - Writing - 1, 2, 3 • from the Texas Almanac 2010–2011 4, 7, 8 - Reading - 1, 2, 3 8 - Social Studies - 2 Instructional Suggestions

SPECIAL LESSON 9 SOCIAL STUDIES TEKS 4 - 4, 6, 21, 22, 23 TEXAS ALMANAC TEACHERS GUIDE 7 - 9, 21, 22, 23 8 - 23 Lady Bird Johnson STAAR 4, 7 - Writing - 1, 2, 3 • From the Texas Almanac 2010–2011 4, 7, 8 - Reading - 1, 2, 3 8 - Social Studies - 2 INSTRUCTIONAL SUGGESTIONS 1. PEN PAL PREPARATION: Students will read the article “Lady Bird Johnson” in the Texas Almanac 2010–2011 or the online article: http://www.texasalmanac.com/topics/history/lady-bird-johnson They will then answer the questions on the Student Activity Sheet and compose an email to a pen pal in another country explaining how Claudia Alta “Lady Bird” Taylor Johnson became a beloved Texas icon. 2. TIMELINE: After reading the article “Lady Bird Johnson,” students will create an annotated, illustrated, and colored timeline of Lady Bird Johnson’s life. Use 15 of the dates found in the article or in the timeline that accompanies the article in the Texas Almanac 2010–2011. 3. ESSAY: Students will write a short essay that discusses one of the two points listed, below: a. Explain how Lady Bird’s experiences influenced her life before she married Lyndon Baines Johnson. b. Describe and analyze Lady Bird’s influence on the environment after her marriage to Johnson. Students may use one of the lined Student Activity Sheets for this activity. 4. SIX-PANEL CARTOON: Students will create and color a six-panel cartoon depicting Lady Bird’s influence on the environment after her marriage to LBJ. 5. POEM, SONG, OR RAP: Students will create a poem, song, or rap describing Lady Bird Johnson’s life. -

CONFERENCE RECEPTION New Braunfels Civic Convention Center

U A L Advisory Committee 5 31 rsdt A N N E. RAY COVEY, Conference Chair AEP Texas PATRICK ROSE, Conference Vice Chair Corridor Title Former Texas State Representative Friday, March 22, 2019 KYLE BIEDERMANN – Texas State CONFERENCE RECEPTION Representative 7:45 - 8:35AM REGISTRATION AND BREAKFAST MICHAEL CAIN Heavy Hors d’oeuvres • Entertainment Oncor 8:35AM OPENING SESSION DONNA CAMPBELL – State Senator 7:00 pm, Thursday – March 21, 2019 TAL R. CENTERS, JR., Regional Vice Presiding: E. Ray Covey – Advisory Committee Chair President– Texas New Braunfels Civic Convention Center Edmund Kuempel Public Service Scholarship Awards CenterPoint Energy Presenter: State Representative John Kuempel JASON CHESSER Sponsored by: Wells Fargo Bank CPS Energy • Guadalupe Valley Electric Cooperative (GVEC) KATHLEEN GARCIA Martin Marietta • RINCO of Texas, Inc. • Rocky Hill Equipment Rentals 8:55AM CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS OF TEXAS CPS Energy Alamo Area Council of Governments (AACOG) Moderator: Ray Perryman, The Perryman Group BO GILBERT – Texas Government Relations USAA Panelists: State Representative Donna Howard Former Recipients of the ROBERT HOWDEN Dan McCoy, MD, President – Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas Texans for Economic Progress Texan of the Year Award Steve Murdock, Former Director – U.S. Census Bureau JOHN KUEMPEL – Texas State Representative Pia Orrenius, Economist – Dallas Federal Reserve Bank DAN MCCOY, MD, President Robert Calvert 1974 James E. “Pete” Laney 1996 Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas Leon Jaworski 1975 Kay Bailey Hutchison 1997 KEVIN MEIER Lady Bird Johnson 1976 George Christian 1998 9:50AM PROPERTY TAXES AND SCHOOL FINANCE Texas Water Supply Company Dolph Briscoe 1977 Max Sherman 1999 Moderator: Ross Ramsey, Co-Founder & Exec. -

The Lives of the Jews of Horažd'ovice

The lives of the Jews of Horažd’ovice In Memoriam WESTMINSTER SYNAGOGUE Our community’s visit to Horažďovice confirmed that no brutality or oppression can ever destroy the spirit of humanity. #e inhabitants of that little town not only showed us their respect and love for those who were so cruelly taken from their midst but also that no amount of fear placed into people’s minds and hearts whether it was through fascism or communism can destroy the spark of godly spirit implanted within us. #e preservation of the Horažďovice scroll and the scrolls from other Czech cities is a reminder of our duty to foster their memories both within the Jewish community and outside, to pass it on to our children and to future generations, forming a chain strong enough to always overcome. It also tells us how important it is to respect one another and not allow prejudice to rear its ugly head. #ere has to be tolerance and understanding and our role here, with our friends in Horažďovice and with the world at large, is to ensure that this never ever should happen again. We must be vigilant and never remain silent in the face of danger or where truth is at stake. We owe this duty to all those who have perished in the horrors of the Holocaust and also to those who today, in different parts of the World, suffer because they are seemingly different. Humanity is only one, just as there is One God whose watchword we say twice a day, Hear O Israel the Lord our God the Lord is One. -

50Th Anniversary Head Start Timeline

Head Start Timeline Delve into key moments in Head Start history! Explore the timeline to see archival photographs, video, resources, and more. 1964 War on Poverty: On Jan. 8, President Lyndon Johnson takes up the cause of building a "Great Society" by declaring "War on Poverty" in his first State of the Union Address. The goal of the War on Poverty is to eradicate the causes of poverty by creating job opportunities, increasing productivity, and enhancing the quality of life. Watch this historic State of the Union Address. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 is enacted and includes programs such as: Job Corps, Urban/Rural Community Action, VISTA, Project Head Start and many more. Watch Small Miracles, a short video about these programs. Case for Early Education: As a former teacher in a one-room schoolhouse in Texas, President Johnson believes strongly that education was the key to breaking the cycle of poverty. Moreover, child development experts have found that early intervention programs could significantly affect the cognitive and socio-emotional development of low-income children. State of the Union, 1964 1965 Cooke Report: Dr. Robert Cooke sets up a steering committee of specialists to discuss how to give disadvantaged children a "head start." The committee develops recommendations that feature comprehensive education, health, nutrition and social services, and significant parent involvement. Read the Cooke Report [PDF, 47KB]. Head Start Launch: On May 18, President Lyndon B. Johnson officially announces Project Head Start from the White House Rose Garden. Head Start launches in the summer of 1965, serving more than 560,000 children and families across America in an eight-week summer program through Head Start Child Development Centers throughout the United States. -

Black Women As Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools During the 1950S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hostos Community College 2019 Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in New York City's Public Schools during the 1950s Kristopher B. Burrell CUNY Hostos Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ho_pubs/93 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] £,\.PYoo~ ~ L ~oto' l'l CILOM ~t~ ~~:t '!Nll\O lit.ti t~ THESTRANGE CAREERS OfTHE JIMCROW NORTH Segregation and Struggle outside of the South EDITEDBY Brian Purnell ANOJeanne Theoharis, WITHKomozi Woodard CONTENTS '• ~I') Introduction. Histories of Racism and Resistance, Seen and Unseen: How and Why to Think about the Jim Crow North 1 Brian Purnelland Jeanne Theoharis 1. A Murder in Central Park: Racial Violence and the Crime NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS Wave in New York during the 1930s and 1940s ~ 43 New York www.nyupress.org Shannon King © 2019 by New York University 2. In the "Fabled Land of Make-Believe": Charlotta Bass and All rights reserved Jim Crow Los Angeles 67 References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or John S. Portlock changed since the manuscript was prepared. 3. Black Women as Activist Intellectuals: Ella Baker and Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mae Mallory Combat Northern Jim Crow in Names: Purnell, Brian, 1978- editor. -

Closing Session: Reflections of the History of Head Start Research

4 Million and Counting: Reflections on 40 Years of Head Start Research in Support of Children and Families Presenter: John M. Love 1965--41 years ago. It’s hard to remember what an amazingly eventful year 1965 was: On January 4, President Lyndon Johnson proclaimed the Great Society in his State of the Union address. In February, the U.S. began bombing North Vietnam in operation Rolling Thunder. On Feb. 2, Malcolm X was assassinated. March 7 became known as “Bloody Sunday,” when civil rights marchers began their trek from Selma to Montgomery and were violently confronted by state troopers. A month later, in a one-room schoolhouse in Texas, President Johnson signed into law the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, which we all know in its latest incarnation as No Child Left Behind. On August 11, the Watts riots began. That year, in Britain, Winston Churchill died—and J. K. Rowling was born. And at the Grammies, Mary Poppins won best recording for children. So with a spoonful of sugar and a ton of sweat and tears, a vast new program for children and families was underway. Within 3 years, Donald Rumsfeld, the new head of the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) would have Head Start as part of his responsibility, guiding the country through an early phase of a different war—the War on Poverty. Research began immediately. One of the first studies in the new Head Start context is a dissertation by an enterprising young University of Chicago doctoral candidate, Diana Slaughter, who investigated the maternal antecedents of African American Head Start children’s academic achievement. -

The Evolution of the Image of the First Lady

The Evolution of the Image of the First Lady Reagan N. Griggs Dr. Rauhaus University of North Georgia The role of the First Lady of the United States of America has often been seen as symbolic, figurative, and trivial. Often in comparison to her husband, she is seen as a minimal part of the world stage and ultimately of the history books. Through this research, I seek to debunk the theory that the First Lady is just an allegorical figure of our country, specifically through the analysis of the twenty- first century first ladies. I wish to pursue the evolution of the image of the First Lady and her relevance to political change and public policies. Because a woman has yet to be president of the United States, the First Lady is arguably the only female political figure to live in the White House thus far. The evolution of the First Lady is relevant to gender studies due to its pertinence to answering the age old question of women’s place in politics. Every first lady has in one way or another, exerted some type of influence on the position and on the man to whom she was married to. The occupants of the White House share a unique partnership, with some of the first ladies choosing to influence the president quietly or concentrating on the hostess role. While other first ladies are seen as independent spokeswomen for their own causes of choice, as openly influencing the president, as well as making their views publicly known (Carlin, 2004, p. 281-282). -

Unwise and Untimely? (Publication of "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"), 1963

,, te!\1 ~~\\ ~ '"'l r'' ') • A Letter from Eight Alabama Clergymen ~ to Martin Luther J(ing Jr. and his reply to them on order and common sense, the law and ~.. · .. ,..., .. nonviolence • The following is the public statement directed to Martin My dear Fellow Clergymen, Luther King, Jr., by eight Alabama clergymen. While confined h ere in the Birmingham City Jail, I "We the ~ders igned clergymen are among those who, in January, 1ssued 'An Appeal for Law and Order and Com· came across your r ecent statement calling our present mon !)ense,' in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. activities "unwise and untimely." Seldom, if ever, do We expressed understanding that honest convictions in I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas. If racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts I sought to answer all of the criticisms that cross my but urged that decisions ot those courts should in the mean~ desk, my secretaries would he engaged in little else in time be peacefully obeyed. the course of the day, and I would have no time for "Since that time there had been some evidence of in constructive work. But since I feel that you are men of creased forbearance and a willingness to face facts. Re genuine goodwill and your criticisms are sincerely set sponsible citizens have undertaken to work on various forth, I would like to answer your statement in what problems which cause racial friction and unrest. In Bir I hope will he patient and reasonable terms. mingham, recent public events have given indication that we all have opportunity for a new constructive and real I think I should give the reason for my being in Bir· istic approach to racial problems. -

Community Engagement and Educational Outreach

Community Engagement and Educational Outreach In November 1977, 20,000 women and men left their jobs and homes in cities and small towns around the country to come together at the fi rst National Women’s Conference in Houston, Texas. Their aim was to end dis- crimination against women and promote their equal rights. Present were two former fi rst ladies–Lady Bird Johnson and Betty Ford—and the current fi rst lady, Rosalyn Carter. Also present were grandmothers and lesbians, Republicans and Democrats, African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinas, and Native Ameri- can women—and the most infl uential leaders of the burgeoning women’s movement—Bella Abzug, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Eleanor Smeal, Ann Richards, Coretta Scott King, Barbara Jordan and others. SISTERS OF ’77 provides a fascinating look at that pivotal weekend and how it changed American life and the lives of the women who attended. Using the fi lm as a focus piece, ITVS’s Community Connections Project (CCP), community engagement and educational outreach campaign, reaches out to: • Organizations that invest in building young women leaders • University and high school students who participate in gender studies, political science, history and social studies • Organizations that promote women’s equal rights, reproductive freedom, lesbian and minority rights • Internet groups that focus on democracy in action, social change and human rights Independent Television Service (ITVS) 501 York Street San Francisco, CA 94110 phone 415.356.8383 email [email protected] web www.itvs.org The goals -

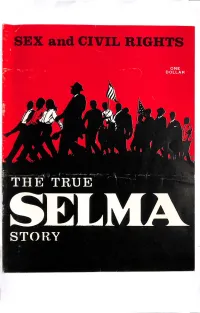

Martin Luther King and Communism Page 20 the Complete Files of a Communist Front Organization Were Taken in a Raid in New Orleans

Several hundred demonstrators were forced to stand on Dexter Ave1me in front of the State Capitol at Montgomery. On the night of March 10, 1965, these demonstrators, who knew that once they left the area they would not be able to return, urinated en masse in the street on the signal of James Forman, SNCC ExecJJtiVe Director. "All right," Forman shoute<)l, "Everyone stand up and relieve yourself." Almost everyone did. Some arrests were made of men who went to obscene extremes in expos ing themselves to local police officers. The True SELMA Story Albert C. (Buck) Persons has lived in Birmingham, Alabama for 15 years. As a stringer for LIFE and managing editor of a metropolitan weekly newspaper he covered the Birmingham demonstrations in 1963. On a special assignment for Con gressman William L. Dickinson of Ala bama he investigated the Selma-Mont gomery demonstrations in March, 1965. In 1961 Persons was one of a handful of pilots hired to support the invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. His story on this two years later led to the admission by President Kennedy that four Ameri can flyers had died in combat over the beaches of Southern Cuba in an effort to drive Fidel Castro from the armed Soviet garrison that had been set up 90 miles off the coast of the United States. After interviewing scores of people who were eye-witnesses to the Selma-Montgomery march, Mr. Persons has written the articles published here. In summation he says, "The greatest obstacle in the Negro's search for "freedom" is the Negro himself and the leaders he has chosen to follow. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6, 2021 No. 4 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was and our debates, that You would be re- OFFICE OF THE CLERK, called to order by the Speaker pro tem- vealed and exalted among the people. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, pore (Mr. SWALWELL). We pray these things in the strength Washington, DC, January 5, 2021. of Your holy name. Hon. NANCY PELOSI, f Speaker, House of Representatives, Amen. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Washington, DC. PRO TEMPORE f DEAR MADAM SPEAKER: Pursuant to the permission granted in Clause 2(h) of Rule II The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- THE JOURNAL of the Rules of the U.S. House of Representa- fore the House the following commu- tives, I have the honor to transmit a sealed nication from the Speaker: The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursu- envelope received from the White House on ant to section 5(a)(1)(A) of House Reso- January 5, 2021 at 5:05 p.m., said to contain WASHINGTON, DC, January 6, 2021. lution 8, the Journal of the last day’s a message from the President regarding ad- I hereby appoint the Honorable ERIC proceedings is approved. ditional steps addressing the threat posed by SWALWELL to act as Speaker pro tempore on applications and other software developed or f this day. controlled by Chinese companies. With best wishes, I am, NANCY PELOSI, PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Speaker of the House of Representatives.