Leith's Traditional Manufacturing and Port Related Industries Around Which Its Growth Was Based

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

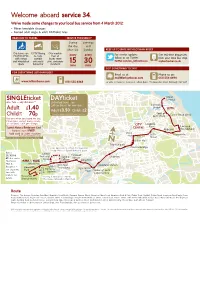

Welcome Aboard Service 34

Welcome aboard service 34. We’ve made some changes to your local bus service from 4 March 2012: • Minor timetable changes. • Revised adult single & adult DAYticket fares. REASONS TO TRAVEL SERVICE FREQUENCY During Evenings the day and Mon-Sat Sunday KEEP UP TO DATE WITH LOTHIAN BUSES Our buses are CCTV filming Our modern For service updates EASYACCESS to help fleet of every every Get real-time departures with ramps combat buses meet follow us on Twitter: from your local bus stop: and wheelchair anti-social strict emissions 15 30 twitter.com/on_lothianbuses mybustracker.co.uk space behaviour standards mins mins GOT SOMETHING TO SAY? FOR EVERYTHING LOTHIAN BUSES Email us at: Phone us on: [email protected] 0131 554 4494 www.lothianbuses.com 0131 555 6363 or write to Customer Services at Lothian Buses, 55 Annandale Street, Edinburgh EH7 4AZ Ocean Terminal Junction Bridge 1.40 3.50 LEITH Foot of Leith Walk Easter Road (foot) CITY Leopold CENTRE Place Lochend Abbeyhill Roundabout West Leith End Marionville Princes St Street Usher Hall Fountainpark Some buses run to or from the Royal Mail Fountainbridge Sorting Office at Sighthill Industrial Estate. Buses Sighthill 25, X25 & Parkhead Industrial Sighthill Terrace Shandon 45 also serve Estate Colleges Hermiston Longstone P&R & Hermiston Bankhead Slateford Station Riccarton – Research Sighthill Roundabout Terminus/ Inglis Green see separate Park Road Water of Leith Mains Rd Mains timetable Riccarton Burtons Visitor Centre leaflets for Riccarton Evening & Sunday buses run via details. (Heriot-Watt) -

Post-Office Annual Directory

frt). i pee Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeannual182829edin n s^ 'v-y ^ ^ 9\ V i •.*>.' '^^ ii nun " ly Till [ lililiiilllliUli imnw r" J ifSixCtitx i\ii llatronase o( SIR DAVID WEDDERBURN, Bart. POSTMASTER-GENERAL FOR SCOTLAND. THE POST OFFICE ANNUAL DIRECTORY FOR 18^8-29; CONTAINING AN ALPHABETICAL LIST OF THE NOBILITY, GENTRY, MERCHANTS, AND OTHERS, WITH AN APPENDIX, AND A STREET DIRECTORY. TWENTY -THIRD PUBLICATION. EDINBURGH : ^.7- PRINTED FOR THE LETTER-CARRIERS OF THE GENERAL POST OFFICE. 1828. BALLAN'fVNK & CO. PRINTKBS. ALPHABETICAL LIST Mvtt% 0quaxt&> Pates, kt. IN EDINBURGH, WITH UEFERENCES TO THEIR SITUATION. Abbey-Hill, north of Holy- Baker's close, 58 Cowgate rood Palace BaUantine's close, 7 Grassmrt. Abercromby place, foot of Bangholm, Queensferry road Duke street Bangholm-bower, nearTrinity Adam square. South Bridge Bank street, Lawnmarket Adam street, Pleasance Bank street, north, Mound pi. Adam st. west, Roxburgh pi. to Bank street Advocate's close, 357 High st. Baron Grant's close, 13 Ne- Aird's close, 139 Grassmarket ther bow Ainslie place, Great Stuart st. Barringer's close, 91 High st. Aitcheson's close, 52 West port Bathgate's close, 94 Cowgate Albany street, foot of Duke st. Bathfield, Newhaven road Albynplace, w.end of Queen st Baxter's close, 469 Lawnmar- Alison's close, 34 Cowgate ket Alison's square. Potter row Baxter's pi. head of Leith walk Allan street, Stockbridge Beaumont place, head of Plea- Allan's close, 269 High street sance and Market street Bedford street, top of Dean st. -

Muirhouse • Pilton • Ferry Road • Leith • Bridges • Prestonfield • Greendykes

service 14 at a glance... frequency During the day During the day During the day During the Mon-Fri Saturday Sunday evening every every every every 12 15 20 30 mins mins mins mins City Centre bus stops Omni Centre See previous page for City Centre bus stops Whilst we’ve taken every effort in the preparation of this guide, Lothian Buses Ltd cannot accept any liability arising from inaccuracies, amendments or changes. The routes and times shown are for guidance – we would advise customers to check details by calling 0131 555 6363 before travelling. On occasion due to circumstances beyond our control and during special events, our services can be delayed by traffic congestion and diversion. 14 Muirhouse • Pilton • Ferry Road • Leith • Bridges • Prestonfield • Greendykes Muirhouse, Pennywell Place — — — 0552 — — 0617 — — 0637 0649 0700 0713 0724 0735 0747 0759 0811 0823 Pilton, Granton Primary — — — 0558 — — 0623 — — 0643 0655 0706 0719 0731 0742 0754 0806 0818 0830 Goldenacre — — — 0603 — — 0628 — — 0649 0701 0712 0726 0738 0749 0803 0815 0827 0839 Leith Walk (foot) — — — 0610 — — 0635 — — 0658 0710 0721 0738 0750 0802 0816 0828 0840 0852 Elm Row 0518 0538 0558 0615 0626 0634 0640 0654 0701 0705 0717 0728 0745 0757 0809 0823 0835 0847 0859 North Bridge 0522 0542 0602 0619 0630 0638 0644 0658 0705 0709 0721 0733 0751 0803 0815 0829 0841 0853 0905 Friday to Monday Prestonfield Avenue, East End 0531 0551 0611 0628 0639 0648 0654 0708 0715 0719 0734 0746 0806 0818 0830 0844 0856 0908 0920 Greendykes Terminus 0538 0558 0618 0635 0647 0656 0702 -

A Free Guidebook by the Leith Local History Society

Explore Historic Leith A FREE GUIDEBOOK BY THE LEITH LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY The Leith Guidebook Explore Historic Leith The Leith Trust seeks to promote a As the Chair of the Leith Trust, it gives current engagement between “Leithers” Leith is an area with a long and I hope you enjoy using this book as a me considerable pleasure to offer an and visitors to our community, in a fascinating history. This guidebook has means to find out more about Leith, its endorsement to this fine and valuable real sense of enhanced community been produced to invite you to explore people and its history. guidebook to Leith. engagement with shared interests the area for yourself, as a local resident in the protection of our environment, or a visitor, and find out more about Cllr Gordon Munro Leith has for centuries been both the the celebration of our heritage and Leith’s hidden gems. Leith Ward marine gateway to Edinburgh and its the development of educational economic powerhouse. So many of the opportunities for all. We can be bound The book has been developed grand entries to our capital city have together in demolishing the artificial in partnership between the Leith come through Leith, most significant of boundaries that any community, Local History Society and the City which was the arrival of King George IV anywhere in the world can thoughtlessly of Edinburgh Council. Thanks and in 1822, at the behest of Sir Walter create, and instead create a real sense acknowledgement must go to the Scott. As to economic impact simply of trust and pride in each other and the History Society and in particular their look up at the friezes and decoration settings in which we live and work. -

PLACES of ENTERTAINMENT in EDINBURGH Part 3 LEITH

PLACES OF ENTERTAINMENT IN EDINBURGH Part 3 LEITH Compiled from Edinburgh Theatres, Cinemas and Circuses 1820 – 1963 by George Baird 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LEITH AMUSEMENTS FROM 1790 7 ‘Tales and Traditions of Leith’ William Hutchison; Decline in Leith’s population, business and amusements. Theatres in chronological order, some of which became picture houses: 10 Amphitheatre, Leith Walk, 1790; Assembly Rooms, Leith, 1864; Theatre, Junction Street, 1865; New Theatre, Bangor Road, 1887; Leith Music Hall, Market Street, 1865; Leith Theatricals, Bonnington Road/ Junction Street, 1865; Leith Royal Music Hall, St Andrew’s Street/Tolbooth Wynd, 1867;Theatre Royal MacArte’s Temple of Varieties, South Junction Street, 1867; Whitfield Hall, 65 Leith Walk, 1874; New Star Music Hall, Foot of Leith Walk, 1874; Princess Theatre, Kirkgate, 1889 – Gaiety Theatre,Kirkgate, 1899 se under The Gaiety, Kirkgate; New Theatre, Bangor Road, 1888; Iona Street Theatre, 1899; Alhambra Theatre of Varieties, Leith Walk, 1914 – closed as a cinema in 1958; Atmospheric Theatre, 1929- The Pringle’s Theatre, 1931- The Studio Theatre, 1932 – Repertory Theatre, 1933 – Festival Theatre, 1935 - Broadway Theatre, 1936 – Gateway Theatre, 1946 – see under 41 Elm Row. Picture Houses in alphabetical order: 21 Alhambra, Leith Walk – see under Theatres; Allison, Laurie Street,1944, see underLaurie Street Picture House; Cadona’s Pictures and Varieties, Coalhill, 1912; meeting with Tom Oswald, M.P., 1962; ; Capitol Picture House, Manderston Street, 1928 – became a Bingo Club in 1961; -

Roadworks & Events Report

Roadworks & events report Effective from 5th October 2018 For further information please contact the following: Edinburgh and Midlothian contact CLARENCE on 0800 23 23 23 Traffic Scotland - information on motorways and City Bypass Forth Bridges Transport for Edinburgh - Lothian Buses and Edinburgh Trams Follow Edintravel on Twitter for regular updates See details of Ward boundaries Entries are arranged by Ward and then by start date. Underlined entries contain links to maps or further information Planned roadworks and events affecting major routes have been approved by the Citywide Traffic Management Group (a partnership between City of Edinburgh Council Transport Officers, local Neighbourhood teams, Lothian Buses and Police Scotland.) new information in this version = temporary traffic lights in use = diversion in operation Ward Street Location Description Traffic Control Start date Finish date Almond GLASGOW ROAD At Ingliston interchange SGN - valve maintenance Lane closure on westbound off-slip to dumbbell roundabout 24/09/18 22/10/18 City of Edinburgh Council - drainage survey for Northbound lane 1 closed, alternating southbound lane closures. Off- Almond A90 At Burnshot Bridge 01/10/18 05/10/18 replacement bridge project peak hours only City of Edinburgh Council - carriageway Road closed to through traffic in 4 phases. Phase 1 - between kirkliston Almond ROSEBERY AVENUE 08/10/18 30/11/18 resurfacing Road and the fire station Outside lanes closed in both directions; Between Quality Street and Clermiston Contraflow west of Clermiston junction; 7pm Almond QUEENSFERRY ROAD Scottish Power - network upgrade 23/10/18 Road North Temporary traffic lights at Clermiston junction; 12/10/18 Clermiston Road North closed to northbound traffic Various lane closures and contraflows. -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Appreciations 1 Article Titles 1 Book Reviews 3 Contributors 4 Family Trees 5 General Index 9 Illustrations 6 Queries 5 Recent Additions to the Library 5 INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) LX.iv.177 A very short visit to Scotslot LIX.iii.144 Agnes de Graham, wife of John de Monfode, and Sir John Douglas LXI.iv.129 An Octogenarian Printer’s Recollections LX.iii.108 Ancestors at Bannockburn LXI.ii.39 Andrew Robertson of Gladsmuir LIX.iv.159: LX.i.31 Anglo-Scottish Family History Society LIX.i.36 Antiquarian is an odd name for a society LIX.i.27 Balfours of Balbirnie and Whittinghame LX.ii.84 Battle of Bannockburn Family History Project LXI.ii.47 Bothwells’ Coat-of-Arms at Glencorse Old Kirk LX.iv.156 Bridges of Bishopmill, Elgin LX.i.26 Cadder Pit Disaster LX.ii.69 Can you identify this wedding party? LIX.iii.148 Candlemakers of Edinburgh LIX.iii.139 Captain Ronald Cameron, a Dungallon in Morven & N. -

58/5 Henderson Street

58/5 Henderson Street | Leith | Edinburgh | EH6 6DE Situated close to the fashionable and sought after shore district, containing a variety of boutique shops, bars and restaurants, this property occupies a second floor position with a well looked after traditional tenement building. 58/5 Henderson Street Situated close to the fashionable and sought after shore district, containing a variety of boutique shops, bars and restaurants, this property occupies a second floor position with a well looked after traditional tenement building. • Hall • Gas central heating • Open plan sitting/dining • Excellent storage room/kitchen • On street parking • Two bedrooms • Potential rent £775pcm • Bathroom (gross yield of 6.6% based on Home Report valuation) • Utility room Description Situated close to the fashionable and sought after shore district, containing a variety of boutique shops, bars and restaurants, this property occupies a second floor position with a well looked after traditional tenement building. This beautiful two bedroom flat is presented to the market in walk in condition. The property consists of an entrance hallway serving all rooms, sitting/dining room with open plan kitchen (fitted with electric oven, gas hob and extractor fan), two spacious double bedrooms, partially tiled modern bathroom, utility room and excellent storage. There is ample unrestricted parking to the front, and an enclosed communal drying area to the rear. The property feels private and is not overlooked by neighbouring properties. Extras The property is being sold with fitted flooring and integrated appliances. Viewing By appointment with D.J. Alexander Legal, 1 Wemyss Place, EH3 6DH. Telephone 0131 652 7313 or email [email protected]. -

Leith Connections – Low Traffic Neighbourhood

Leith Connections – Low Traffic Neighbourhood Design Breakout Workshop Agenda • Introductions • Housekeeping • Area 1 – Leith Links • Area 2 – The Shore • Area 3 – Coburg St & Henderson St Housekeeping • Chair to help facilitate and ensure everyone gets a fair opportunity to speak. • Please use the hand's up function – Chair will note these and invite people to speak. • Stick to the question/topic of that part of the meeting. Flag items that you’d like to return to later in the Chat box and the Chair will note these and bring them back to the group for discussion. • Any questions which you don’t have opportunity to ask or receive response will be recorded and responses shared via email to group. • Discussions are being recorded for record keeping purposes. • Respect the speaker and their view and allow them to finish their point. • Try to be succinct, we have limited time and want everyone to be able to get there points across. • We welcome feedback on ways to improve how the group functions as we go along. Breakout Sessions Smaller group sessions to consider the detail of the proposals and feedback. 3 2 Assigned teams meeting rooms with max. 10 participants. Short presentation of proposals and discussion on designs in 3 areas: 1. Leith Links 2. The Shore 3. Henderson / Coburg St 1 A) Traffic Proposals B) Placemaking Area 1 – Leith Links Overview: Area 1 – Leith Links You said: 1. High volumes of through traffic (north-south; and east- west) 2. High levels of concerns regarding speed and volume of traffic 3. Concerns raised over the safety of walking and cycling 4. -

Ocean Terminal • Leith • Canonmills • Stockbridge • Tollcross • Morningside • Sighthill • Gyle

service 36 at a glance... frequency During the day During the day Monday to Friday Saturday & Sunday every every 20 30 mins mins City Centre bus stops Whilst we’ve taken every effort in the preparation of this guide, Lothian Buses Ltd cannot accept any liability arising from inaccuracies, amendments or changes. The routes and times shown are for guidance – we would advise customers to check details by calling 0131 555 6363 before travelling. On occasion due to circumstances beyond our control and during special events, our services can be delayed by traffic congestion and diversion. See previous page for City Centre bus stops 36 Route: Ocean Terminal, Ocean Drive, Commercial Street, The Shore, Henderson Street, Great Junction Street, Bonnington Road, Broughton Road, Eyre Place, Henderson Row, Hamilton Place, Deanhaugh Street, Leslie Place, St. Bernards Crescent, Dean Park Crescent, Queensferry Road, Randolph Cliff, Queensferry Street, Hope Street, Charlotte Square, South Charlotte Street, Princes Street, Lothian Road, Earl Grey Street, Home Street, Leven Street, Barclay Place, Bruntsfield Place, Morningside Road, Morningside Drive, Morningside Grove, Glenlockhart Road, Craiglockhart Avenue, Lanark Road, Inglis Green Road, Longstone Road, Calder Road, Bankhead Avenue, Bankhead Crossway North, Bankhead Drive, Cutlins Road, Lochside Avenue, Lochside Crescent, Edinburgh Park, Gyle Avenue, Gyle Centre. Return via above route reversed to Cutlins Road, Bankhead Drive, Bankhead Broadway to Bankhead Crossway North then as outward route reversed -

The Golfer's Annual for 1869-70

ONE ILLIKG AND SIXPEN : No. G-/PO2.. * « GOLFER'S ANNUAL FOR 18.69-70. COMPILED AMD EDITED BY CHARLES MACARTHFR. AYE: TROTTED AND PUBLTSIIED BY HENRY & GRANT. 16 PKEFACE. GOLF, the National Game of Scotland, and one of the most enticing of out-door exercises, is now so extensively indulged in as to deserve, at least, some statistical publication. A few years ago a work similar1 to this was published, but was not continued. Since then the practice of the Game has rapidly extended; and many solicitations having recently boon made to the Editor to bring out a GOLFER'S ANNUAL, his love for the Game, and his desire to gratify Golfers and others, induced him to undertake the work. The ANNUAL contains much interesting matter, such as a record of all the Golf Clubs at present known, with their respective. Competitions and Tournaments during the last three years, the llules of the Game observed by different Clubs, as well as other incidents; and the details of tho Competitions for the Champion Belt since its institution by the Prestwick Golf Club have been deemed of sufficient importance to entitle them to consider- able space. While imperfections may be apparent, it. is hoped that, though not claimed on its merits, the object of the ANNUAL will secure it a passport for this year, and that sufficient encouragement will be j^'ven for the appearance of its suc- cessor. The thanks of the. Editor avo due, and are now warmly tendered, to the Secretaries of the different Clubs, and others, who so readily furnished information in aid of his efforts.' 1JRUNTON C'OTTAGK, LONDON ROAD, EDINBURGH, Fubfuaiu, 1S70. -

Edinburgh Film Events Diary

Edinburgh on the Silver Screen Edinburgh Film Events Diary Edinburgh has long been a favourite of film makers for its MONTH EVENT DESCRIPTION WEB stunning skyline, historic character and vibrant city life.This unique city has enjoyed a starring role in hundreds of movies January Scotland Galore! Movies for Hogmanay. filmhousecinema.com Filmhouse film quiz Probably the trickiest quiz in the country every 2nd Sunday. filmhousecinema.com/cafe-bar/ and TV productions over the years, from period dramas to Cameo film quiz Answer film questions to win prizes every 3rd Tuesday. facebook.com/CameoFilmQuiz thrillers and romantic comedies, with everything in between! February Mountain Film Festival Mountain adventure through films, lectures and exhibitions. edinburghmountainff.com/ Filmhouse film quiz Probably the trickiest quiz in the country every 2nd Sunday. filmhousecinema.com/cafe-bar/ Cameo film quiz Answer film questions to win prizes every 3rd Tuesday. facebook.com/CameoFilmQuiz With ‘set-jetting’ a growing trend and more and more film fans Write Shoot Cut Short film networking night. Free to submit, free to attend. screen-ed.org/2013/04/16/write-shoot-cut-short-film-night/ visiting the locations of their favourite movies, where better to explore a city’s relationship with the big screen than Edinburgh? March Italian Film Festival Premieres of the best Italian films. italianfilmfestival.org.uk Filmhouse film quiz Probably the trickiest quiz in the country every 2nd Sunday. filmhousecinema.com/cafe-bar/ This map provides a taster of the wide range of films that were Cameo film quiz Answer film questions to win prizes every 3rd Tuesday.